Badhotel Niederlößnitz – Wikipedia

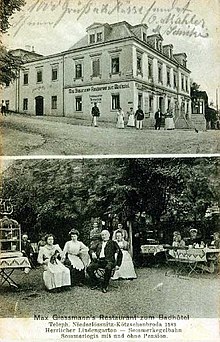

The former Badhotel Niederlößnitz , also Badschlösschen Called, lies in Burgstraße 2 (former address: Obere Bergstraße 62) in the Niederlößnitz district of the Saxon city of Radebeul. In the same house was located Max Gießmanns Restaurant Zum Badhotel . The hotel was given up in 1914.

The building is now a apartment building. The estate located north of the Oberen Bergstrasse is located in Monument protection area Historical vineyard landscape Radebeul . The property was under the name of Gurlitt in 1904 Bad-hotel inventorized as a building and art monument, with the statues in particular being described. [first] The building, which was created from two former, connected winegrowers, is a cultural monument. [2]

The two-storey residential assembly is almost directly on the footpath on a sloping corner plot, while the green and open spaces in the east and above all on the slope rising to the north are located. The lower building is seven window axes on Oberen Bergstraße and has three window axes on Burgstrasse. Due to the assembly with the second core building, a total length of nine axes on Burgstrasse.

The entrance between the two former winegrowers takes place from the west into the all -round overlasted courtyard. This is rounded up by a gallery to which a cast iron staircase leads. The gallery is used to open up the upper floor.

The two old core buildings carry shuffled hipped roofs with dormers, in the basement there are still old toned wine cellars.

In the front to the Upper Bergstrasse there is a basket arch portal with a keystone, probably from the former winegrower house, and formerly above a double -sided free staircase, the entrance from the street to the restaurant. In front of the portal, a up -to -date balcony has recently been set out of the upper floor.

The facades are simply plastered today. The windows of the southern building are comprised by elaborately profiled sandstone walls, which are supplemented on the upper floor by horizontal compacts.

The former winegrower house, standing on the Oberen Bergstrasse, dates from 1720, the north behind in 1791, dates to the courtyard 1791 .

In 1818, the retired Dresden city physics Friedrich August Röber, who had already acquired the vineyard ownership in 1800, moved in there; Röber died in 1827. In 1844 the vineyard estate was owned by the pharmacist Hager.

The reindeer Traubott Leberecht Gießmann acquired the winery in 1849. In 1851 the southern front building was widened by eleven Ellen, and the northern winegrow house was built in 1853. In 1858 a barn was built. The conversion of the two side by side to the hotel took place by Gießmann in 1862. The following year Gießmann received the concession into a wine bar and opened his associated vineyard. In the following years, the hotel was also successful as a public tub pool operation, whereupon the name of the establishment. There was also a garden terrace and a summer railway. In addition to the inexpensive dishes, Gießmann was also for his “well -groomed own wines” [3] known.

Like several other buildings in Lößnitz, the Badhotel also received the appendix from the vernacular -Chlösschen (Bennoschlösschen, Mätressenschlösschen), it was Badschlösschen called.

The so-called Gießmann′sche Weinberg reached from today’s Burgstraße to the east to the confluence of the Bodelschwinghstraße into Obere Bergstrasse and he pulled uphill from the upper Bergstrasse to over the slope; It consisted of four vineyards: the two Krause’s vineyards , to the Strauche Mittelberg and the sold in 1918 Local mountain . In the middle of the vineyard, the score Mountain, the mountain gorge through which Burgstrasse runs on the plateau.

The winery had to Hofmann around 1853 Meißner Netherland A size of 26 fields 263 square [4] (Almost 15 hectares), of which a good part steep slopes. In the following years, Gießmann converted five to five and a half Scheffelsaat (almost one and a half hectares) of vineyard areas in arable land. [5]

Traugott Leberrecht’s son Max Gießmann inherited the Badhotel, while when the vineyard extended far to the edge of the slope, the upper area went to his brother Ernst Louis Gießmann, who built the Friedensburg mountain restaurant there. Max had his bathing hotel rebuilt on the inside with restaurant 1874/75.

Between 1876 and 1878, the Gießmann tunnel was driven through the mountain to irrigate the hotel company, which was to introduce water from black pond on the plateau, but was subsequently insufficient. Today the mountain water is launched into the sewage system.

The street side was increased by the new owner Ferdinand Emil Müller (also Emil Fr. Müller) by the master builder Adolf Neumann in 1884. Müller was also the owner of the Friedensburg of Gießmann’s brother. In the following years, the Badhotel changed the owner and the tenant several times, but kept his name.

The Bodelschwinghstraße, which is limited to the east, which runs north and then right angles to the west, was built on the property in 1893, the lowest part was separated to the north of the wine mountain. The villas on this street and on the part of the Oberen Bergstrasse were built between 1895 and 1905 (for example Villa Augusta, Villa Luise, also the villa for Ernst Louis Kempe), majority by Adolf Neumann.

In the Describing representation of the older construction and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony In 1904 Gurlitt in 1904 as part of the property “An original sundial in sandstone” and in front of the entrance door, the small double -sided open staircase on the south side, and in the business garden several statues made of sandstone, thematic children’s figures from the first half of the 18th century: ” Painting with a palette and canvas, sculpture with bust, autumn with wine, winter with fur and coal pool. These four approx. 1 m high. Fishermen with a fish, shepherd, a lamb wearing, two snapshots with an honor and a cloth over the head. This a little smaller. ”

The hotel was in 1914 [6] (1919) [5] set. French prisoners of war involved in the construction of the water tower were housed in the side building during the construction period in 1916/1917.

After 1919, the closed management company was converted into an apartment building.

- Manfred Richter: Bad hotel. In: Niederlößnitz of Anno then. Accessed on November 10, 2012 .

- Manfred Richter: The Gießmann water tunnel. In: Niederlößnitz of Anno then. Accessed on November 10, 2012 .

- ↑ Cornelius Gurlitt: Niedellar spit; … BAD-Hôt. In: Descriptive representation of the older construction and art monuments of the Kingdom of Saxony. 26. Heft: The art monuments of Dresden’s surroundings, part 2: District Chanately Dresden-Neustadt. C. C. Meinhold, Dresden 1904, p. 133.

- ↑ Entry in the monument database of the state of Saxony on the monument ID 08950331 (PDF, including map section). Accessed on March 31, 2021.

- ↑ Bad hotel. In: Frank Andertt (Red.): Stadtlexikon Radebeul. Historical Manual for the Lößnitz . Ed.: City Archives Radebeul. 2., slightly changed edition. City Archives, Radebeul 2006, ISBN 3-938460-05-9, S. twelfth f .

- ↑ Karl Julius Hofmann: The Meißner Netherlands in its natural beauties and oddities or the Saxon Italy in the Meißner and Dresden areas with their towns. A folk book for nature and Fatherland friends topographically historical and poetic . Louis Mosque, Meißen 1853. p. 710. ( Online-Version )

- ↑ a b Manfred Richter: Bad hotel. In: Niederlößnitz of Anno then. Accessed on November 10, 2012 .

- ↑ Volker Helas (editor): City of Radebeul . Ed.: State Office for the Preservation of Monument Saxony, large district town of Radebeul (= Monument topography of the Federal Republic of Germany. Monuments in Saxony ). SAX-Publishe, Beucha 2007, ISBN 978-3-86729-004-3, S. 88 f .

Recent Comments