Man’yōheū – Wikipedia

The Man’yōshū ( Japanese Album or. Many leaflets , in inscription too Manioseu , [first] Dt. “Collection of the tens of thousands of leaves”) is the first great Japanese poemthology. It is a collection of 4,496 WAKA poems, which among other things the Kokashū and the Ruijū Karin ( Category Julin ) contains. The Man’yōshū takes a special position in the pre-classical literature of Japan (Nara period). It was not compiled by 759 and, in contrast to all subsequent collections of the Heian era, but by private hand, primarily by the poet ōtomo no yakamochi based on Chinese model. The extent of 20 volumes, which he has created more or less randomly, served as a model for the following imperial collection of poems.

According to traditional annual census, the oldest poems can be dated back to the 4th century, [Note 1] However, most date between 600 and 750.

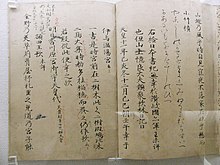

The compilation is in the Man’yōgaki , one off Man’yōgana Existing syllable shape, in which Chinese characters serve to present the pronunciation. The poems were recorded exclusively in Kanji, the Chinese characters taken over by the Japanese. These characters were used both ideographically and phonetically.

In Man’yōshū, 561 authors are named with names, including 70 women. In addition, a quarter of the poets remain anonymous, so that another 200 authors can be accepted. Among them included Otomo No Tabito (665–731), Yamanoue No Okura (660–733) and Kakinomoto No Hitomaro.

The title has always caused difficulties to translate. Especially the second of the three ideograms in the title man-yō-sh can be understood differently. The characters man ( Ten thousand ) common means today Ten thousand but was also used to express an indefinite large number, comparable to the term myriad. The characters Shū = collection is largely clear in its meaning. The ideogram yō is often in meaning Blatt has been understood and too Koto no ha , literally: Word sheet ( words , kotoba ) in the sense of word, speech, poem has been expanded [Note 2] [2] . This view leads to the most common translation of the term “collection of tens of thousands of leaves”. The second ideogram is also in importance manei , manyō many Generations ( Ye Shi ). In this case the title was about Poems of many generations .

The editors of the work are unknown, but the poet ōtomo No Yakamochi should have contributed significantly to the creation of the collection. Over 561 poets are particularly known, but about 25% of the poets who have contributed to the diversity of Man’yōshū are unknown. The oldest poems date from the 4th century. Most poems of the anthology, however, date between 600 and 750. The majority of the work make 4173 short seals Mijika-uta , the so-called Tanka out of. In addition, the Man’yōshū 261 contains long poems NAGA-UTA or Finech , and 61 expressly marked Seburt , symmetrically built six -line poems.

While the later imperial collections of poems follow a strict content principle (spring, summer, autumn, winter, farewell, love, etc.), the arrangement of the poems in Man’yōshū is still largely disorganized. The poems can be divided into six groups that are distributed over the entire text corpus:

- Not satisfy the bow oder zōka ( Miscellaneous song ) – Mixed poems, such as congratulations poems, travel songs and ballads.

- Slammon ( Hear ) – Poems in mutual statement of a friendly feeling. An example of this is a poem that Coupons , the sidewalk of the emperor Tenji to the younger brother of the emperor, Prince Oama, wrote when he gave her to understand her during a hunting trip.

- Knock ( elegy ) – Elegia, which includes songs about the death of the members of the imperial family.

- Hiyuka ( Metaphor ) – Allegorical poems

- Shill not to satisfy the bow or Eibutsuka ( Chanting ) – Mixed poems with special consideration of nature and the four seasons

- Shiki Sōmon – Mutual statements taking into account the seasons [Note 3]

Already at the beginning of the 10th century you could no longer say who and when the Man’yōshū had been put together. This was primarily due to the fact that the tenno and with them the court in the subsequent government periods until the Engi period turned to Chinese poetry again. One cannot therefore say with certainty who the mergers of this extensive work were. The only thing that is certain is that the collection ended in the late Nara period [Note 4] .

The explanations of the priest Keichū ( Deed ) [3] [Note 5] According to the Man’yōshū, in contrast to the collections from twenty -one, era, which were put together on imperial command, was created as a private collection of the poet Yakamochi by the Klan ōtomo [4] . He himself, involved in various political matters, died in dubious circumstances.

The main sources of Man’yōshū, that Kojiki and the Nihonshoki (or Nihongi mentioned) are mentioned even in the anthology. Furthermore, works of individual poets, memoirs, and diaries, but also oral, served as sources. In some cases, the original source or even the compiler’s personal opinion has been specified for the poem. Another characteristic of Man’yōshū is the repetition of the poems in slightly modified versions.

Only Emperor Murakami dealt with the collection again. In the two centuries that had passed until then, it had largely been forgotten how the consistently Chinese characters could be read. Murakami therefore used a five -member commission that began to write down the reading in Cana. This as Smash (“Old reading”) known notation of 951 followed Jiten (“Second reading”) of a six -member commission. The reading of 152 remaining poems was then developed in the 13th century by the Mönch Sengaku ( Shinten , “New reading”).

One of the most important source books of Man’yōshū was that Ruiju Karin ( Category Julin , “Forest classified verses”) [5] , which was lost in later time. It was completed by Yamanoe Okura, one of the first Man’yōshū poets and an enthusiastic admirer of Chinese literature. Not much is known about the work, but it is assumed that it served as a template for the first two volumes. Another source provided that Cocon ( Ancient song collection , “Collection of old poems”). In addition, the Hitomaro , Kanamura , MUSHIMARO and SAKIMARO known collections mentioned.

Usually a poetry or a group of seals in Man’yōshū is the name of the author, a foreword and not infrequently a note. In the foreword and note, the reason, date and location, but also the source of the poem are mostly given. All of this is written in Chinese. Even Chinese seals, even if very rarely, occur in the books of Man’yōshū. The poems themselves are written in Chinese characters. It is noteworthy that the characters were mostly borrowed from Chinese because of their phonetic value, which is man’yōgana referred to as. In some cases, the characters were also used semantically, with the corresponding Japanese reading ( ideographic use ). The Kana, the syllable in Japan, only developed from the manyōgana. Several Kanji were able to have the same phonetic value. This was a great challenge for the translation of the Man’yōshū.

The poem (song) in Man’yōshū consists of several verses, which usually alternately contain five and seven magnes. Original was probably noted in lines at sixteen or seventeen characters.

Tanka [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

The most common form in anthology that occurs most frequently and still preserved today is Tanka . This form of poem consists of five verses with 31 dimen: 5/7/5/7/7.

Finech [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

In addition, the so -called long poems or Finech . A chōka also consists of 5 or 7 dimers per verse and is completed with a seven -moral verse: 5/7/5/7/5… 7/7. The long density are formed according to the Chinese model. They often follow short poems, so -called KAESHI-UTA or Leg ( Anti -song , Repetition poem ). Formally, these are tanka that represent a summary or addendum in a concise form.

The longest Finech However, 150 verses do not cross in anthology. There are a total of 262 of the long poems in Man’yōshū, some of which are made by Kakinomoto Hitomaro, one of the most important poets. The Finech even lost importance in the 8th century, while the meaning of the Tanka increased.

Seburt [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

In addition to these two shapes, the “sweeping socket” can also be found ( Seburt ). It occurs 61 times in the collection of the ten thousand leaves. It is the combination of two Half -poem , to the Words ( Song song ), which is characterized by the two -time repetition of the triplet 5/7/7, i.e. 5/7/7/5/7/7. The Seburt It became more and more unbroken over time and was finally forgotten.

Bussokusekika [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

Finally, there is still a special form that Bussokusekika ( Buddha’s footsteps , literally “Buddhaffenspurg density”) with only one copy in Man’yōshū. It is reminiscent of a stone monument that has the shape of Buddha’s footprint and the 752 was created in the Yakushi temple near Nara. There are 21 songs that have been preserved to this day. Six verses with 38 syllables are characteristic of this form: 5/7/5/7/7/7.

Rhetorical medium [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

Neither emphasis, pitch, syllable lengths nor rhyme are used for the effect of the poem. This is attributed to the peculiarity of the Japanese language, in which each syllable ends with a vowel.

On the one hand, alliterations were used as rhetorical means and on the other hand the parallelism that im Finech was used. In addition, so -called KAKE KOTOBA ( Rig ) used, word games with homonyms, in which a reading can take different meanings depending on the characters. The Japanese word matsu Can, for example, wait , but also Kiefer mean depending on whether the characters ( wait ) or ( loose ). Another typical Japanese stylistic device are Makura kotoba ( Pillow ), Called “pillow words” because they lean on the reference word semantically. In their function they are with the Epitheta adversaries (decorative obitudes) comparable. These are individual words or sentences, generally with five syllables that are connected to other liters or phrases in poems. Due to the semantic overlay, the poet was able to generate associations and sounds and thereby give the poem up and down heights and depths. Makura kotoba Already in the Kojiki and Nihonshoki but were only established by Kakinomoto Hitomaro in Man’yōshū.

The longer ones Joshi ( Preface ), Introductory words, are structured in a similar way to the pillow word, but longer than five dimers and were mostly used as a form of prologue.

Of the three means mentioned, this is KAKE KOTOBA Formally the simplest, but very significant in Japanese poetry and a great challenge for translators.

Example: Book II, Poem 1 of Iwa No Hime:

| Kanbun | Japanese reading | ROMAJI [6] | translation [7] |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Junzhi Long -standing slave Yamada Welcoming Wait for it to wait |

You go |

Kimi Ga Yuki |

Yours go away |

YAMATAZU NO IST HIER MAKURA KOTOBA ZU mukae . The metric scheme is: 5-7-5-7-7.

In its quality, the Man’yōshū is by no means subject to one of the well -known Chinese collections and in quantity it can be compared to Greek anthology. In contrast to another important collection of poems, the Kokin Wakashū, are contained in the Man’yōshū both the courts of the farm and that of people in the country. The range even extends to Sakimori , the “seals of the border guards” and the seals of the eastern provinces, Azuma UTA , in their rough dialect. In addition to the magnificent reproduction of city life, lively descriptions of rural life coexist. This anthology reflects Japanese life at the time of its emergence and illustrates touch with Buddhism, Shintoism, Taoism and Confucianism.

The creations of the imperial family are one of the early works, which have a preference for the folk song or ceremonial. A good example of this is the poem attributed to Emperor Yūryaku (456–479) YAMATO NO KUNI (“The Land Yamato”), which opens the Man’yōshū.

To the individual books [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

As already mentioned, the Man’yōshū consists of 20 volumes. It is assumed that the first two books of the collection were put together to command the emperor. Book I includes works of the period between the reign of Emperor Yūryaku (456–479) and the beginning of the Nara era. Book II, on the other hand, covers a longer period: it contains songs that are attributed to the Emperor Nintoku (313–399) and those dated 715. Both books are less extensive compared to the other volumes, the poems appear in chronological order and are written in the so -called “early palace style”. Book III describes the period between the reign of Empress Suiko (592–628) and the year 744. Contrary to the predecessors, the book rather contains the seals of the countries. You can generally say that the Poets of the Otomo clan are extremely present in the first three books of Man’yōshū.

In the book IV there are exclusively Sōmonka From the Nara period. The key term of the book IV is requires it . Probably the best translation of the term is “desire”, such that is never replied. As a result, frustration arises that comes into its own.

Book V covers between 728 and 733 and contains some important ones Finech . In view of the extensive period of time and the poet, the book VI is very similar to the books IV and VIII. It includes 27 Finech And some travel and banquet seals. The book VII as well as the books X, XI and XII, equipped with anonymous seals, covers the period between the reign of the Empress Jitō (686–696) and the Empress Genshō (715–724). It contains several songs from the Hitomaro collection and draws another important part, 23 Seburt , a. The books XI and XII can be assigned to the Fujiwara and the early Nara period. The seals of these books have a folk poetry character. Book IX reveals seals from the time between the government period of the Emperor Jomei (629–641) and, apart from one Tanka of Emperor Yūryaku, 744. The songs were largely related to the Hitomaro and Mushimaro collections. Book XIII shows a unique repertoire of 67 Finech on what the majority of the time of the Kojiki and Nihonshoki is dated. However, some copies are unambiguously from the later periods. The collection of Seals of the eastern provinces If you find neither the authors nor the date of the compilation is known in Book XIV, but there is a clear difference to the provincial poems, in style and language. Book XV includes a number of sea seals, written by the members of the legation to Korea around 736 and some love poems, dated 740, which were exchanged by Nakatomi Yakamori and his beloved Sanu Chigami. The seals dealt with in Book XVI describe the period between the reign of the Emperor Mommu (697–706) and the Temyō era (729–749).

In general, the poet ōtomo No Yakamochi is considered the compiler of the first 16 books of Man’yōshū. It has also been proven that there is a gap between the books I to XVI and the following four.

Books XVII to XX are viewed as personally collected works by ōtomo No Yakamochi. Each of the four books belongs to the Nara period, book XVII covers 730 to 740, book XVIII 748 to 750 and book XIX 750 to 753. Overall, these three volumes contain 47 Finech , the content of the book XIX is determined by two thirds by Yakamochi’s works, here is the majority of his masterpieces. Book XX includes 753 to 759. Here are the Sakamori wrote down, the songs of the border guards, which guard the Kyusshū coast. Name, rank, province and status of each individual soldier are recorded together with the associated seal. The year 759, the last date in Man’yōshū, attached to the poem concluded by Yakamochi.

Kakinomoto NO Hitomaro [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

From half of the 7th century, a professional status of the poets at the court emerged, where Kakinomoto no Hitomaro (around 662 to around 710) played a not insignificant role. Nothing is known about his life, but he had a significant share of 450 poems, including 20 Finech , in Man’yōshū. The poems he created can be divided into two categories: those that he made in his function as Hofpoet, so to speak, on order and the one he created out of his personal feelings. The former includes elegies to the death of members of the imperial house. Especially in the Finech he showed his whole artistic skill. By using joshi and makura kotoba accompanied by refrain -like repetitions he knew how to shape the sound of the poem. The long poem came to an end with Hitomaro in addition to its climax. The court poet Yamabe No Akahito tried the tradition of the Finech To continue, however, he was unable to submit to Hitomaro’s masterpiece. For the downfall of the Finech There were several reasons. The Finech known only a few stylistic means, such as the design with 5 and 7 syllables. As already mentioned, rhymes or accents played no role, contrary to the European poem. Furthermore, the long poems were praise to the emperor, with only a few exceptions. The seals were by no means designed in a variety of ways. Finally, the seals of Hitomaro did not embodies an ideal, but only expressed the absolutely loyal attitude towards the “big ruler”.

The second group of his poems, the personal sensations, presents him as an excellent poet, especially with regard to the elegies that he wrote about the death of his wife.

YAMABE NO AKAHITO [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

The central themes of Man’yōshū were love and pain about death. The poems that deal with it related their metaphors from the immediate natural environment, which expressed the sensation of love by flowers, birds, moon and wind, the pain, on the other hand, used metaphors such as mountains, rivers, grass and trees. There was undoubtedly a special affinity for the change of seasons. However, the concept of nature was not treated in its entire range. So it happened that, for example, the moon as the motif served many poems, but the sun and the stars rarely occurred in the seals. Furthermore, the coastal sea was preferred to the vastness of the lake.

The poet Yamabe no Akahito, known for his landscape seals, wrote his poems, in contrast to Hitomaro, even if there was no special occasion. The topics of his poems were not huge mountains, but the Kaguyama, a hill of 148 meters, not the sea, but the little bays with their fishing boats.

Because Akahito only created natural density and in no way developed in this direction, he inevitably became a specialist in natural poetry. He discovered that poetry was also possible without intuition and originality. So he became the first professional poet of Japanese poetry, which describes its historical meaning.

Yamanoue NO OKURA [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

Another poet played an important role in Man’yōshū: Yamanoue No Okura. You don’t know anything about your origin, but the Nihonshoki reports that a “Yamanoue No Okura, without Hofrang” was a member of the legation to China in 701. After three years of stay, he returned to Japan and was raised to the nobility in 714. In 721 he became the crown prince teacher. In 726 he was sent to Kyusshū as governor of Chikuzen. Several years later, he fell ill and wrote a “text, himself for consolation in view of the long suffering” in 733, in which he described the symptoms of his illness.

During the China stay, Okura perfected his ability to write Chinese texts that reveal a strong Taoist and Buddhist influence. In the foreword to one of his poems, he cites the Sankō and the Gokyō , Essential Confucian terms. Another poem that he wrote down, an elegy on the death of his wife (v/794) shows massive Buddhist influences.

Okura’s love for family and children was a big topic of his poems. His already mentioned poem “Song when leaving a banquet” was decisive, because nobody apart from him has ever written such verses again. Since the EDO period, it has even been shameful for a man to move away from a banquet for family reasons. A second topic of his poems represented the burden of age. Accompanying his “poem about the difficulty of living in this world” in which he complains about the immediate age.

The third large subject area of Okuras includes seals about misery, poverty and heartlessness of the tax collector. The following poem, a counter verge to Finech Dialogue about poverty (V/892), makes his thoughts clear:

- Bitter and misery

Is life to me.

Can’t fly away

I’m not a bird. - (In/853)

This topic was never touched by any of his contemporaries or successors.

ŌTomo NO YAKAMOCHI [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

The son of ōtomo no Tabito, Yakamochi (718? –785) spent his youth in Kyusshū. After his father died, he became the head of the house ōtomo. His political career was not unsuccessful: he served as a governor of various provinces, but often stayed at the farm in Nara. In 756 he was involved in an unsuccessful plot against the Fujiwara influential at the court, which reduced the star of his political career.

Ōtomo no yakamochi is one of the main components of the Man’yōshū, which contains around 500 poems of him, the last one from 759. His earnings are neither in the originality nor in the language or sensitivity of his seals, it is more because Yakamochi is It managed to refine the expression of nature sensation and thus to the world of Kokinshu (around 905) if not to that of the Shin-kokinshū (around 1205).

On the one hand, the poetocracy of the 7th century the long poem regarded the long poem as a representative form of poetry and used it primarily to special and collective occasions. On the other hand, the lyrical poem developed in the Tanka , the short poem that became the valve of personal feeling. The recurring motif of the Tanka Formed the love between man and woman, occupied with metaphors from the natural environment. Although the assumption of the firm culture had already started, the Chinese ideas could not yet penetrate the deep layers of thought. Even during the heyday of Buddhist art in Temyō-era (729–749), the Buddhist thoughts did not manifest themselves in the poetry of the nobility. “The poets of the 8th century described a nature (Yamabe no Akahito), which was detached from human matters, felt the psychological rejection of love (ōtomo no sakanoue), or sang the nuances of a highly refined world of history (ōTomo no yakamochi)”. As the central theme of poetry, the love and the poets of the courtyard remained the highest bid.

SAKIMORI UTA [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

On the one hand, representative of the folk poetry were SAKIMORI UTA ( Prevalent song ), Songs of the border guards ( sakimori ) and on the other hand Azuma UTA ( East song ), Songs of the eastern provinces. The content of the SAKIMORI UTA , present with 80 songs in Man’yōshū, closed together from three main topics. About a third of the songs complain about the separation from the woman or lover, another third applies to parents or mother (only in one case to the father) at home and only the rest deals with the actual service of the soldiers. However, the latter are by no means praise to military service, often the soldiers complain hateful about their work:

- What a common guy!

To make myself a borderline

Since I am sick. - (XX/4382)

There was a hierarchy among the border guards: a subgroup leader came to 10 soldiers each. In contrast to the simple soldier, the sub -group leaders were sometimes handed down completely from songs:

- From then on

I don’t want to look back

wants to go out,

to serve my gentleman

as its most undertaking sign. - (XX/4373)

Azuma UTA [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

The emotional sensations of humans in the country were not fundamentally different from those of the court. One thing was common, for example, the common Japanese worldview. This is proven by the Azuma UTA , Over 230 short poems anonymous poets of the provinces. It is assumed that they were created in the 8th century. Almost no characteristics of Buddhism are in the Azuma UTA Included, which can be assumed that the Urjapanese culture, as it was still preserved at the time, is reflected.

As in the poetry of the courtyard, the love between man and woman also forms the central motif here. 196 of the over 230 poems are made by the compilers of the group of Sōmonka assigned, but are among the remaining some who more or less directly address love. There is hardly any natural poetry contrary to the poets of the courtyard, detached from sensation of love. Only 2 poems mention death. The description of love between man and woman has only a few verbs that occur accordingly. These can be divided into two groups: those that relate to direct physical contact and those who treat the psychological side of love. For example, one of the first not , sleep in the sense of sleeping. The other group includes verbs like kofu , love, or the deceased , yearn.

Azuma UTA reflects the folk belief that tries to even influence them by means of oracle, the interpretation of words of pre -indulgence and the burning of the shoulder blade of a Hirsches, which is directly close to the future.

- The literature of the east in individual representations. Volume X. History of Japanese literature by Karl Florenz, Leipzig, C.F. Amelangs Verlag, 1909.

- Katō Shūichi: A history of Japanese Literature. Vol.1, Kodansha International, Tokyo, New York, London, 1981 ISBN 0-87011-491-3

- Frederick Victor Dickins: Primitive & Mediaeval Japanese Texts . Translated into English with Introductions Notes and Glossaries. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1906 ( Digitized On the Internet Archive – commented, English translation of Man’yōshū and Taketori Monogatari).

- Frederick Victor Dickins: Primitive & Mediaeval Japanese Texts . Transliterated into Roman with Introductions Notes and Glossaries. Clarendon Press, Oxford 1906 ( Digitized on the Internet Archive-Transliteration of Man’yōshū and other works including a detailed description of the Makura-Kotoba used).

- Alfred Lorenzen: Hitomaro’s poems from Man’yōshū in text and translation with explanations . Commission publisher L. Friederichsen & Co., Hamburg 1927.

- S. or (HRSG.): Man’yōshū . In: Japan. An Illustrated Encyclopedia. Kodansha, 1993. ISBN 4-06-205938-X, S. 919.

- Robert F. Wittkamp: Writing games with landscape and memory. For use in the sign in Man’yōshū . In: East out the last 48, 2009, S. 251–270.

- Robert F. Wittkamp: memory poetry in Man’yōshū -Writings with Mnemo-Noetian verbphrases. In: R.F. Wittkamp (ed.): Memorial. Text, picture, voice, body – media of cultural memory in pre -modern Japan . München: Cast, 2009, St. 198-240.

- Robert F. Wittkamp: To three new ones Man’yōshū -Spendant with regard to English -language processing (review articles). In: Asian studies (As / E / E / E / B) LXV 2, 2011, S. 57-594.

- Robert F. Wittkamp: Difference and loss – aspects of mediality in Man’yōshū . In: News from the Society for Nature and Ethnology 185–186, 2012, S. 5–21.

- Robert F. Wittkamp: seasons and cultural memory in Japan – from Man’yōshū To the present. In: Greub, Thierry (ed.): The image of the seasons in the change in cultures and times. Munich: W. Fink, 2013, pp. 99–115, plates pp. 8–10.

- Robert F. Wittkamp: Old Japanese memory poetry – landscape, writing and cultural memory in Man’yōshū (Wan Ye Ji) . Band 1: Prolegomenon: landscape in becoming the Waka poetry. Band 2: Writing games and memory poetry . Ergon, Würzburg 2014, ISBN 978-3-95650-009-1.

- Robert F. Wittkamp: On the paradigm of space presentation in old Japanese literature – mythical and aesthetic spaces in Man’yōshū and Kojiki . In: Journal of the German Morge Society Bd. 168, Heft 1, 2018, S. 179–205.

- Robert F. Wittkamp: Old Japanese text generation and the Chinese roots – shown in a correspondence from Man’yōshū . Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2021 (in: Treatises for the customer of the Eastern country, Vol. 120). ISBN 978-3-447-11547-6.

- Robert F. Wittkamp: “Three masterpieces” of the Old Japanese poetry – Yakamochi as a characters and his references to Chinese literature. In: Journal of the German Morge Society Band 171, Heft 1, 2021, S. 191–220.

- Robert F. Wittkamp: “bloated time” in narrative poetry – Yakamochi’s introductory sequence too Man’yōshū-Band 19. Asian studies AS/EA 75, 1, 2021, S. 131–161.

- Robert F. Wittkamp: The ruler pulls for hunting – narrative poetry in the “ Man’yōshū the early days ”. In: Orientations 32 (2020), 2021, S. 1–34.

- Robert F. Wittkamp: Where is the literature? Notes on Alexander Vovin’s Man’yōshū (Review article) . In: Bochum yearbook for East Asia research 43 (2020), 2021, S. 211–227.

- Robert F. Wittkamp: A Narratology look at a Correspondeen Yakamochi and Ikenushi: Reading Man’y’yōshū Poems 17: 3962 AS A Closed and Self-CON Tained Work. In: tōzai gakujutsu kenyūsho kiyō (Minister of East and West Academic Institute) 54, 2021, s. 69–96 (download PDF).

- Ananieva, Anna and Robert F. Wittkamp: Gardens of memory in Man’yōshū . In: R.F. Wittkamp (ed.): Memorial. Text, picture, voice, body – media of cultural memory in pre -modern Japan . München: trial, 2009, S. 37-53.

- J.L.Pierson (transl.): The Manyōśū. Translated and Annotated, Book 1 . Late E.J.Brill LTD, Leyden 1929

- The Japanese Classics Translation Committee: The Manyōshū. One Thousand Poems Selected and Translated from the Japanese . Iwanami, Tokyo 1940

- Kenneth Yasuda (transl. And ed.): The Reed Plains. Ancient Japanese Lyrics from the Manyōśū with Interpretive Paintings by Sanko Inoue . Charles E. Tuttle Company, Tokyo 1960

- Theodore de Bary: Manyōshū . Columbia University Press, New York 1969

- Jürgen Berndt (transl. And ed.) Red leaves. Old Japanese poetry from the manyōshū and Kokin-Wakashu . Insel Verlag, Leipzig 1972

- Ian Hideo Levy (transl.): The Ten Thousand Leaves: A Translation of the Man’yōshū, Japan’s Premier Anthology of Classical Poetry . Princeton University Press, New Jersey 1987 (first edition 1981)

- Shūichi katō: Japanese literature history . Scherz Verlag, Bern [u. a.] 1990

- Horst Hammitzsch (ed.): Japan manual . Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart 1990

- Graeme Wilson (transl.): From the Morning of the World . Harvill Verlag, London 1991

- Donald Keene: Seeds In The Heart . Columbia University Press, New York 1999

- ↑ It is the first four tanka of the second book, the Iwa No Hime, wife of the emperor Nintoku (traditional reign: 313–399).

- ↑ Karl Florenz notes that this use could have been used for the first time in the preface to the Kokinshū in the early 10th century, which means that this interpretation was in time.

- ↑ Florence calls six groups, Katō Shūichi, on the other hand, three groups: Zōka, Sōmonka and Banka. History of Japanese Literature, p. 59.

- ↑ According to information from the Keep – ( Sakaika Monogatari ) and Yotsugi -Monogatari ( Glory story ) Waren Tachibana NO MOROE ( Tachibana Brothers ) and some dignitaries the compilers of the Man’yōshū. However, it is doubtful whether this information is reliable, since on the one hand the sources come from the 11th century and because on the other hand the compilation was continued beyond Tachibana’s death 757.

- ↑ It is the 31-volume comment Manko-Daishopoki ( Takumi Manyo ).

- ↑ Rororo lexicon in nine volumes: Duden-Lexikon-paperback edition , Mannheim 1966, S. 1347 (Bd. 6).

- ↑ History of Japanese literature, p. 80.

- ↑ Deed . In: Digital version Japanese name dictionary+plus At Kotobank.jp. Kodansha, Retrieved on November 20, 2011 (Japanese).

- ↑ Florence: History of Japanese literature, p. 81.

- ↑ Category Julin . In: Digital version Japanese name dictionary+plus At Kotobank.jp. Kodansha, Retrieved on November 20, 2011 (Japanese).

- ↑ Annoted copy of the Man’yōshū ( Memento of the Originals from April 26, 2012 in Internet Archive ) Info: The archive link has been used automatically and not yet checked. Please check original and archive link according to the instructions and then remove this note.

- ↑ Translation of Karl Florenz, History of Japanese Litterature, p. 78.

Recent Comments