State debt – Wikipedia

When Public debt If one refers to the summary of a state, i.e. the liabilities of the state to third parties. The public debt is usually reported gross, which means that the liabilities of the state are not stalled with its state assets (or share of this).

According to Eurostat, the public debt in the Maastricht Treaty is defined as a nominal gross political debt of the state sector after consolidation, i.e. offsetting claims and liabilities within the state sector. The state sector comprises the central state and extra -keeps, countries, communities and social security. [first] [2] For EU members (and here in particular members of the Euro system), according to the Maastricht, convergence criteria applies that the public debt status in relation to the nominal gross domestic product (the so-called debt rate) should not exceed 60%.

State debt is not only a object of knowledge of economics, but also concerns business ethics, law, political science or public business administration. As one of the knowledge of economics, this deals with the role of the state of the state as a debtor. If the state revenues and government spending in the state budget are in an imbalance and lead to a budget deficit, this can only be compensated for by borrowing (e.g. via government bonds) if corresponding cuts in government expenditure are not possible at short notice and increases in state income are not to be expected at short notice. In Germany, “all federal obligations to be met in Germany are considered to be government debt, unless they belong to ongoing budgetary management. The liabilities to be completed as part of the cash and household management are therefore excluded ”. [3]

In its story to be trampled down to the Roman Empire, the state debt repeatedly caused crises from the state finances. [4] During the Roman Empire, however, governments were only in debt in exceptional cases, but in the Middle Ages the high phase of the public debt began. In particular, war expenditure drove up the government debt. As early as the 12th century, the public loan developed when the Italian city state Genoa loan from bankers received a loan of 25% in 1121, which even increased to 100% in 1169. [5] Eduard III. In May 1340, a state loan of a Hanseatic C that Hanseatic Consortium against the pledging of the wool tariffs of all English ports. [6] The state bankruptcy of the city was preceded by the establishment of a market for government debt in Florence in 1345. In 1557, Spain turned its state loans into government bonds unilaterally due to the crisis and thereby drove several banks into bankruptcy. [7] On November 29, 1596, Philipp II declared Spain’s state bankruptcy for excessive interest payments and hired the payments. [8]

Mercantilism has been positive at the latest since 1689 because of its positive and comprehensive attitude towards the state debt of the state debt and operated systematic long -term public debt. [9] Mercantilist teaching understood borrowing as a legitimate state covering, because the economic policy aimed at expansion was only financed with the help of loans. Mercantilist Jean Bodin in 1583 was not the state loan in his seven sources of state revenue, [ten] Even if he treated the public loan in connection with the government debt. Already Veit Ludwig von Seckendorff as a representative of cameraism – the German version of Mercantilism – in 1655 held the state loan for “correct use”, but not in “chronic deficit economy” to be appropriate and joined for orderly state finances. He did not completely reject the government bond. The French theologian Jean-François Melon de Pradou claimed in 1734 that the state’s debt was the debt of the right hand in the left hand, whereby the associated body is not weakened at all ( French The debts of a state are debts of the right hand to the left hand, the bodies of which will not be weakened ). [11]

The physiocrats turned away from debt -friendly mercantilism and moved into the opposite position. As a result, David Humes Staatsulden-Pessimism was expressed in 1752, because “either the nation must destroy the state debt or the government will destroy the nation” ( English either the nation must destroy public credit, or public credit will destroy the nation ). [twelfth] There was also a departure from Mercantilist debt policy in the classic economists. For Adam Smith, the state supported only unproductive work with its debts, as described in his book in his book of the prosperity of the nations. It is considered the founder of crowding-out, through which private demand is displaced by state loan-financed demand because the state displaced private market participants from the capital market and goods market by its interest-insensitive behavior. [13] “The enormous increase in state debt, which is currently crushed all larger states and will probably bring about their ruin, is more of the same shape everywhere.” [14] On September 6, 1789, the later US President Thomas Jefferson wrote to James Madison: “No generation can accept debts more than she can repay during the time of her existence” ( English Then no generation can contract debts greater then maybe paid during the course of it’s own existance ). [15] Immanuel Kant called for the eternal peace of September 1795 that “no state debt should be made in relation to the external state” because he saw the cause of wars in state loan. Because states could wage wars with the loan and states that would be defeated by credit bankruptcies. [16]

David Ricardo saw the most terrible scourge in government debt in 1817, which was ever invented to the nations. [17] He provided a circulatory-theoretical explanation for the equivalence of tax and credit financing, since the loans to be paid by the state are financed by taxes, because the tax only goes from those that they pay, to those that they receive, i.e. H. From taxpayer to the state creditor ”. [18] In the Kingdom of Prussia, the question of the public debt by the State Department Act introduced in 1820 was closely related to the participation of representatives of the state and promoted the emergence of parliamentarianism.

The nullity of government debt (repudiation) first appeared in Mississippi in May 1841 as a result of the cotton crisis of 1839 because the government bond concerned was not approved in parliament. [19] In Germany, Friedrich List considered the state loan system to be “the most beautiful creations of recent state art and a blessing for the nations” in 1841. [20] Years later, Karl Marx described the view in 1867 that a people would be richer with increasing public debt as “credo of capital” [21] , he and other socialists were of the opinion that it was only an instrument for accumulation of private capital. [22] Lorenz von Stein wrote in his textbook of financial science in 1875: “A state without public debt either does too little for his future or he demands too much of his present”. [23] Adolph Wagner also approved public debt in 1879 because the state should invest and had to finance the resulting government spending. [24]

However, the debt -friendly representatives overlooked the negative effects that could lead to moratoriums or state bankruptcy. Argentina hired the debt service between 1829 and 1857. Another moratorium followed in April 1987, and in January 2001 the country finally exclaimed the state emergency, combined with the insolvency for government bonds in February 2001. Italy’s state budget has been characterized almost continuously by high public debt in May 1861. [25] In October 1861, Mexico announced a moratorium due to the high debt, Napoleon III. provided the pretext for French intervention in December 1861. Between 1820 and 1916, Colombia explained no less than 13 state bankruptcy. [26]

In 1936, John Maynard Keynes was convinced in his book General Theory of Employment, Interest and the Money that the state had to encounter a recession with increased government expenditure at the expense of temporary public debt and thereby an economy resurrection through anti -cyclically increased state demand (deficit financing, English Deficit spending ). [27]

After the Second World War, the state debt, which prompted the rating agencies in 1982, accepted the rising risks of country risks with a state rating. State debt initially achieved a higher extent from March 1997 in Asia (Asia crisis), then from May 1998 during the Russia crisis and finally in Europe. [28]

The evaluation of the public debt is controversial in economics: While David Ricardo and many of his contemporaries disapproved of them, a temporary public debt can be justified from the Keynesian perspective to smooth the economic course. Ricardo described her as “the most terrible scourge that had ever been invented for the nation”. [29] In his economic theory, Keynes, on the other hand, took the view that the state should temporarily increase its government debt in an economic downturn from Deficit Spending. [30]

Economic limits [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

States can only fault, since from a certain degree of debt investors and creditors begin to doubt the repayment ability. The assessment of the creditworthiness depends primarily on the primary surplus rate, i.e. the budget balance without considering the interest payments, based on GDP. In the event of high debt, comparatively high tax revenue or low government expenditure is required in order to be able to finance the interest payments.

For states with high public debt, not only the interest rates that investors demand for their loans increase, but also reduces the number of investors who are still willing to make money available. A highly indebted state can get into a vicious circle of ever higher financial obligations (interest and repayment of existing debts) and more and more limited access to the financial market. This can end with the loss of creditworthiness or even the insolvency of the state (state bankruptcy), especially if there is debt in foreign currency.

Monetary state financing [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

If a state or state network has its own currency and the central bank – unlike in countries with independent central banks – is obliged to carry out the decisions of the executive, the government can make monetary policy decisions, for example reducing or increasing the amount of money. From a state-controlled increase in money supply, debts were often repaid and economically or armaments programs were financed, for example in the economic policy of the global economic crisis or in times of war. In extreme exceptional situations that threaten the existence of a state, inflationary risks are inevitable by increasing the money supply (reparation claims after the First World War, financing of war and war sequence costs) and the payment of credit suffering from tax revenue is usually impossible, and is also in the The precarious situation does not provide sufficient credit rating for the required loan volume for economically weakened economies.

This “financing through the grading press” can lead to a loss of credibility and creditworthiness. In addition to a perhaps the desired effect of the devaluation of the external value, the population fully employed can also lead to an undesirable devaluation of the financial assets in the relevant currency. Because of the inflationary risks is after Art. 123 AEU contract The monetary state financing in the European Union is prohibited, as has been more and more than independent institutions since the Second World War in general, which have to protect the stability of the currency.

Also the policy of quantitative loosening, which was used after 2001 by the central banks of Japan, the United States and the Eurozone, among others [thirty first] is considered by critics as a form of indirect monetary state financing that hardly differs from direct financing. In addition, the ECB’s monetary policy has been pursuing the goal of generating moderate inflation, including the slow devaluation of financial assets, at zero interest.

The public debt can be distinguished:

According to internal and external creditors [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

One can classify the debt of a state according to whether the creditors are domestic or foreign economic entices (people, households, banks, companies), also called internal and external debt. [32] This classification is the highly simplified idea that internal debt of the state is raised in debt. The idea is “simplified” because only with a theoretical equal distribution – i.e. if a state would owe the same amount of government liabilities to every of its citizens or households and that every citizen or household would have tax liabilities in the amount of at least this same amount – the state State debt in this way would only be directed against itself that consolidation or offsetting would be possible and that there would be practically no public debt. However, external debt is burdening a state without the state being able to offset it with its citizens or households because actual third parties are the creditors. [33]

According to your own and foreign currency [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

One can classify the debt of a state according to the currency in which the capital services (interest and repayment) must be affected to the creditors. This classification is the idea of whether a state may affect the currency itself in which he has to do his capital services. This would be the case for debt in a national currency and a high dependence of the national central bank on the state governments. This influencing potential decreases even if the central bank is independent. In the case of a community currency such as the euro, there is only a weak influence, while in the case of debt in a real third currency, there is no longer any influence.

After delimitation of the state debtor institutions [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

Especially in a federal state, there may be different bodies, e.g. B. the federal government, countries, cities and municipalities that have accepted debt. Likewise, debts can be accepted with several countries, as is the case for projects in the EU. There must also be a distinction whether debts have been included in the core budget of a regional body or in an extra account. In this context, a distinction can be made between the public debt of the public core households and the public debt of the overall public budget (core households + extra -holders).

According to different measurement concepts [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

A distinction must be made between the published credit market debts of public budgets in financial statistical delimitation, the Maastricht debt and the colloquial debt level. Depending on the invoice style practiced, the measurement concept used can always be based on camera (amount of the liabilities) or double data (liabilities + provisions). Not least because of the lack of total state data, double debt levels i. d. R., however, can only be intended for part of the local authorities.

According to the cause of the creation [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

Here, after the financing of the economic and structural budget deficits through public debt, the economic and structural budget deficits are usually classified. By definition, economic deficits are in the scale with economic surpluses, i.e. economic deficits in the economy departure are compared to economic surpluses in the economic upturn. If the gross domestic product is the same as the production potential, the production gap is zero, then the economic deficit is zero according to its definition. [34] [35] Specifically, the structural deficit in percent of the potential gross domestic product is defined as the overall deficit minus the economic deficit. The economic deficit is multiplied by the production gap by the difference of the elasticities of state revenue and government spending on the automatic stabilizers. [36] The distinction between the economic and structural state deficit goes into the regulations on the debt brake and the European fiscal pact.

After explicit and implicit public debt [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

The state debt presented so far is the Explicit public debt . These are all liabilities directly recognizable from the state budget such as government bonds. However, there are also expenditure and liabilities that arise in the future, which are often not visible from the current state budget, but can or will burden later households ( implicit government debt Or shadow debt). This applies in particular to future payment obligations such as civil servants. This non -transparency is favored by the cameralism of most state budgets. In addition, the consumption of substance of state assets is only shown in the change in capital assets, while the far greater depreciation requirement in public infrastructure is not taken into account. On the other hand, the Doppik requires that provisions must be formed in the balance sheet under certain conditions for the future.

Against the background of the euro crisis, the European Central Bank (ECB) now warned of the consequences of shadow debt in the euro countries. The guarantees for other EU member states and their own credit institutions could increase the debt of Germany by 11.2% to a state debt rate of around 90% of gross domestic product (GDP). [37]

It is criticized by the official representations of the public debt that, in addition to the published debt, there can be other liabilities that are not limited or published in other contexts, even though they are fully used by the state. Such a debt, which is prompted by a state budget, but is not shown in this budget (e.g. outsourcing in side households), is referred to as hidden public debt.

In addition, the concept of implicit state debt is used, which mainly includes future pension and pension payments. Bernd Raffelhüschen is of the opinion that, in contrast to the precaution and completeness principle imposed on the private sector, the published government debts generally result in a too favorable presentation of the actual debt, since no future pension expenditure (as a retirement provision) is shown in the measurement of the state debt. [38]

According to the European system of overall economic calculations, state extra holding and special funds are attributed to the overall state -owned households. [2]

The effect of public debt on national and international economies can be read using the following example. If, for example, the state debt (gross) reaches the amount of gross domestic product (state debt rate therefore 100%) and – with an assumed interest rate of 6% – are 33% of the gross domestic product, the tax revenue is already loaded with 18% interest (rate of coverage). After the debt service, only about 80% of the tax revenues for its actual tasks of state financing remain the state. [39] Conversely, in the event of negative interest rates due to indebtedness, income on the part of the state can occur. [40] [41]

Financial crises and economic growth [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff argue that high public debt increases the financial risks for creditors and would conjure up the risk of financial crises. Financial crises are the result of increasing public debt, on the other hand, financial crises would again lead to new public debt. [28] Reinhart and Rogoff thus see a problem in high public debt and argue on the basis of empirical data that high public debt has a negative impact on economic growth. In her data, a state debt rate of over 90% on average led to a negative economic growth. Yeva Nersisyan and L. Randall Wray, on the other hand, contradict interpretation that the state debt rate is the cause of lower growth. It was only a correlation, but no causality was shown. It is more plausible that reduced growth is preceded by a higher public debt, since countries in recessions tend to increase their debt ratio, while the debt rate is reduced from the recovery phase. [42] [43]

Thomas Herndon, Michael Ash and Robert Pollin, on the other hand, come to a different result in 2013 when the raw data is evaluated again: Countries with a state debt rate of over 90% would have a positive economic growth of 2.2% and not as from Reinhart and Rogoff claimed by – 0.1%. Reinhart and Rogoff selectively selected data, weighted them inappropriately and incompletely evaluated due to an error in the spreadsheet calculation. This questions the need for a rigorous austerity policy, which was also operated in Europe and the USA on the basis of this original false evaluation. [44] [45]

Distribution of debts to the generations [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

Critics of a debt policy argue that the current generation lives the current generation at the expense of future generations (generation balance sheet). According to this, government debt is postponed to the future, which are then “supported by the following generations”.

This connection is in macroeconomic theory as BARRO-RICARDO equivalence proposition known and includes as a core message that the permanent income of households does not change due to the new debt (= tax reduction) and thus has no effect on the expenses (= demand) of households, since the households are the future tax payments caused by the current debt are already anticipated in the present by saving. In this context, the question is discussed whether the securities issued by the state or correspond to ongoing taxation, since the economic subjects recognize that the securities must be repaid with future tax increases. For this reason, an increase in the budget deficit that is not accompanied by the state’s expenses should follow an increase in the savings rate in the same amount.

The Keynesian critics of this neoclassical theory, on the other hand, argue that a tax cut can be effective as a demand, since they defuse the liquidity restriction (inability to accept loans) of many households because they are more liquid. Empirical studies show that the Barrro-Ricardo equivalence cannot be fully valid, since the tax cut (→ Reaganomics) carried out in the USA did not lead to an increase in the savings rate (the savings rate dropped of approx. Nine percent a year 1981 to below five percent in 1990).

Austerity measures and rationality trap [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

A so -called rationality trap can be subject to the assessment of combating public debt through austerity measures. What sounds plausible at first glance and illuminates every private household (“I have too high debts, so I have to save.”), Can have unexpected consequences for the economy: If the state cuts its expenses, for example by using transfer payments to industry and Households in the form of grants and subsidies inevitably have an impact on the revenue side of the state budget: to the actual and/or perceived reduction in income of households, they can react with a reduction in consumption and an increase in savings tendency. As a result, the aggregated or overall economic demand drops and leads to falling or negative economic growth, which also reduces the state’s tax revenue, which can effectively lead to a negative savings effect. Individual rationality (savings reduced debts) is therefore in conflict with collective rationality (if everyone saves, this could have no or negative effects on the state budget). [forty six]

creditor [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

The state’s debt is distributed to domestic and foreign creditors. The debt compared to these two creditor groups must be assessed differently. While domestic debt leads to a redistribution of assets within the economy (see redistribution and generation problem in this article), liquidity flows into another economy for interest and repayment payments when debt abroad. The repayment of foreign debts will withdraw liquid funds to the economy in the future, but it can be argued here that states like Germany (the German state and German households together) could be a net believer in a global point of view (depending on the credit states’ creditworthiness ), which is why a global debt reduction could contribute to an inflow of liquid funds. The arguments of the tax increase/distribution problem and the economic-theoretically supported warning of too high abroad by net debtor countries can thus be separated from the argument of the stress of generations.

When credit institutions in turn accept the money at a central bank, the central bank is indirectly borrowing money to the state. [47]

Replacement of private investments [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

Especially if it is assumed that there is a limited supply of money or credit (money supply) and in this respect increased capital demand that the respective capital offer – so that the price of credit granting the loan – is increasingly making an increased demand for “money “The financing costs of the companies and displacements their planned investments, which is why competitiveness such as economic growth suffered.

This economic-negative effect of increasing public debt is called crowding-out effect. However, Wilhelm Lautenbach, for example, already pointed out in 1936 that essential basic assumptions for this model model were only limited. [48] If the state spends a large scale of credit -financed funds for domestic investments, private investments can be replaced if (1) the level of utilization of domestic industry for the production of the investment goods is already very high and (2) no replacement can be imported. Even if the production capacity and the possibility of imports have not yet been exhausted, there can be a crowding out if higher prices for investment goods make private investments less profitable. If the investments are then refused, there has been a repression. The crowding out argument is not based here on a scarcity of money, but on the limited production capacity of an economy (real economy displacement).

Inflation effects [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

To finance the government’s expenditure, [49] In countries with a non -independent central bank there is often an incentive to make this only by gaining the central bank. If additional funds are not withdrawn elsewhere (see also reduction in balance sheet), goods production and offering or even decreases in relation, this results in an inflation tendency. Especially when war financing was made by the respective central bank, as was done by the Reichsbank, for example, this often led to hyperinflation (see German inflation 1914 to 1923) and the following currency reform (such as 1924 and 1948). [50]

Japan’s economic development in the 1930s, on the other hand, shows that the financing of government spending on money creation and expansion of the money supply can also lead to an overcoming crisis in moderate inflation. The income grew by 60 percent between 1931 and 1936, the internal inflation was 18% within the same period, the external value of the yen fell 40%. [51]

Conversely, a monetary policy of a central bank that is too independent can also be deflation, [52] Create credit clamp and banking crisis (as to the German banking crisis in 1931).

Keynesian justification [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

Keynesian is seen by state debt as an economic policy agent against deflations and to overcome adhesive. With his economic balancing mechanics, Wolfgang Stützel showed how comprehensive debt repayment through the state’s excess of income would force the private sector from a Keynesian perspective, which leads with a negative keynes multiplier in crisis and deflation. [53] Therefore, the state is asked by various Keynesian economists to fault to avoid recession and deflation in order to enable the private sector to form a corresponding financial assets.

Deficit Spending only comes for a properly understood Keynesian policy after a relaxation or task of the restrictive monetary policy responsible for an economic crisis. Before the outbreak of the global economic crisis, John Maynard Keynes argued violently against a foreseeable deflation policy [54] the central banks and against the gold standard. [55] In 1930, Keynes called for an expansionary monetary policy to overcome the crisis from those responsible for the central banks. [56] Only after the task of the gold standard and with the beginning of an expansive monetary policy of the central banks, Keynes also advocated a policy of the deficit donation of the state to overcome mass acquisition, because no feasible reduction in interest rates will be sufficient in a difficult deflation, the crisis will end . [57]

In the opinion of Keynesian theorists, the state should operate an anti -cyclical financial policy: In order to conclude a staggeration, the state can bring about an economic upswing by means of higher government expenditure or by means of tax cuts ( Deficit spending , “Start -up financing”), with which private consumption could be promoted and industrial investments could also increase (in subsequent dependency). In return, the income and consequently the tax revenue would increase. The debt paradox may arise: the additional tax revenues transfer the costs to repay the government debt.

See also: Keynesianism

Distribution policy effects of public debt [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

The distribution policy effect of the public debt is controversial. There are several aspects to be distinguished:

The interest burden, which must be applied by the state by taxes or expenditure and the creditor is paid, reduces the state’s scope and therefore requires political decisions. If the taxes are not to be increased, the shares of the household that contribute to redistribution will decrease, unless other expenses are shortened even more in the favor.

However, if debt -financed investments of the state are useful, for example in infrastructure or the temporary support of companies in order to favor or secure sustainable tax revenue and thus more than compensate for the above -mentioned effect, this measure increases the scope of the state. This idea can also be found in the justifications for economic stimulus packages in times of crisis. In many cases, evaluating the chances of success of the respective measures or their omission is obviously difficult and is discussed extensively in politics and science.

Twin deficit [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

If there is both a budget deficit of the state and a current account deficit in a country, one speaks of a twin deficit. In this situation, the increasing public debt is partially financed through foreign loans. This is only possible as long as foreign investors trust that the exchange rate of the currency of the state is stable. If trust is eliminated, it is necessary to either increase interest rates or to restrict domestic consumption, which in turn affects economic growth. In extreme cases, public debt contributes to the emergence of financial crises.

Different countries have implemented legal limits for state new debt in recent years:

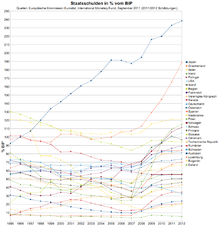

In order to be able to compare the public debt of various countries, it must be taken into account that the economies are different in size. That is why the overall debt is set in relation to the gross domestic product (GDP). Example: Germany’s public debt was around 61% of GDP at the end of 2018, the rate of Austria was almost 74%. [58]

According to the International Monetary Fund of September 2011, the debt rate above the limit of 60% of GDP (Maastricht criteria) was uncritical at 46 out of 171 countries above the limit of 60% of GDP (Maastricht criteria). In 13 countries of it, it was even over 100%. In half of the countries listed in 171 by the International Monetary Fund, the debt rate was less than 44%.

While the debt ratio could be reduced in 91 countries from 2000 to 2007 in 91 countries, it increased in 24 countries, in 30 countries it remained about the same (less than five percentage points change). From 2007 to 2011, however, the debt rate worldwide increased in 83 countries, while it could be reduced in 39 countries and remained about the same in 48 countries. These differences in debt development can be attributed to the financial crisis from 2007 and the subsequent euro crisis, of which many countries worldwide are directly or indirectly affected.

State debt in industrialized countries [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

The phase of economic growth from the end of the Second World War until the early 1970s enabled most industrialized countries to reduce debt. After that, the debt rose rapidly in almost all OECD countries until 1996; Then she sank slightly again. The most important reason for the strong increase in German government debt in the 1990s was reunification. The average of the OECD countries in 2001 was 64.6% (for strong differences: Australia 20.9%, Japan 132.6%, Germany 60.2% according to OECD criteria). The financial crisis from 2007 driven debt in the euro countries to almost 85 percent of GDP (before the crisis: 70 percent). [59]

For state debt there are slightly varying information from various sources. The following table reproduces the establishment of the Austria Chamber of Commerce (as of May 2019 and Source EU Commission, OECD). Italics figures are forecasts.

Eurozone (19)

European Union (28), but not euro zone (19)

not European Union (28)

> 90% > 60% > 30% ≤30%

| Land | Average 2000–2009 |

Average 2010–2014 |

2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 * | 2019 * | 2020 * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 98.4 | 103.9 | 108.8 | 94.7 | 99.7 | 107.5 | 106.4 | 106.1 | 103.4 | 102.0 | 101.3 | 100.7 | |

| 63.9 | 79.1 | 58.9 | 67.0 | 81.8 | 75.3 | 71.6 | 68.5 | 64.5 | 60.9 | 58.4 | 55.6 | |

| 5.0 | 8.6 | 5.1 | 4.5 | 6.6 | 10.5 | 9.9 | 9.2 | 9.2 | 8.4 | 8.5 | 8.5 | |

| 39.6 | 53.2 | 42.5 | 40.0 | 47.1 | 60.2 | 63.4 | 63.0 | 61.3 | 58.9 | 58.3 | 57.7 | |

| 65.6 | 90.4 | 58.9 | 67.4 | 85.3 | 94.9 | 95.6 | 98.0 | 98.4 | 98.4 | 99.0 | 98.9 | |

| 107.1 | 166.8 | 104.9 | 107.4 | 146.2 | 178.9 | 175.9 | 178.5 | 176.2 | 181,1 | 174.9 | 168.9 | |

| 33.6 | 108.1 | 36.1 | 26.1 | 86.0 | 104.1 | 76.8 | 73.5 | 68.5 | 64.8 | 61.3 | 55.9 | |

| 103.2 | 123.2 | 105.1 | 101.9 | 115.4 | 131.8 | 131.6 | 131.4 | 131.4 | 132.2 | 133.7 | 135.2 | |

| 15.0 | 42.5 | 12.1 | 11.4 | 47.3 | 40.9 | 36.8 | 40.3 | 40.0 | 35.9 | 34.5 | 33.5 | |

| 20.1 | 38.5 | 23.5 | 17.6 | 36.2 | 40.5 | 42.6 | 40.0 | 39.4 | 34.2 | 37.0 | 36.4 | |

| 8.9 | 21.4 | 7.2 | 7.4 | 19.8 | 22.7 | 22.2 | 20.7 | 23.0 | 21.4 | 20.7 | 20.3 | |

| 65.7 | 67.4 | 60.9 | 70.0 | 67.5 | 63.4 | 57.9 | 55.5 | 50.2 | 46.0 | 42.8 | 40.2 | |

| 50.0 | 64.5 | 52.1 | 49.8 | 59.3 | 67.9 | 64.6 | 61.9 | 57.0 | 52.4 | 49.1 | 46.7 | |

| 68.0 | 82.5 | 66.1 | 68.6 | 82.7 | 84.0 | 84.7 | 83.0 | 78.2 | 73.8 | 69.7 | 66.8 | |

| 64.1 | 118.7 | 50.3 | 67.4 | 96.2 | 130.6 | 128.8 | 129.2 | 124.8 | 121.5 | 119.5 | 116.6 | |

| 38.3 | 49.1 | 49.6 | 34.1 | 41.2 | 53.5 | 52.2 | 51.8 | 50.9 | 48.9 | 47.3 | 46.0 | |

| 26.4 | 57.9 | 25.9 | 26.3 | 38.4 | 80.4 | 82.6 | 78.7 | 74.1 | 70.1 | 65.9 | 61.7 | |

| 46.5 | 82.2 | 58.0 | 42.3 | 60.1 | 100.4 | 99.3 | 99.0 | 98.1 | 97.1 | 96.3 | 95.7 | |

| 57.9 | 82.8 | 55.7 | 63.4 | 56.8 | 108.0 | 108.0 | 105.5 | 95.8 | 102.5 | 96.4 | 89.9 | |

| Eurozone (19) | 68.9 | 90.6 | 68.2 | 69.3 | 85.0 | 94.4 | 92.3 | 91.4 | 89.1 | 87.1 | 85.8 | 84.3 |

| 35.8 | 18.3 | 71.2 | 26.8 | 15.3 | 27.1 | 26.2 | 29.6 | 25.6 | 22.6 | 20.5 | 18.4 | |

| 41.0 | 44.4 | 52.4 | 37.4 | 42.6 | 44.3 | 39.8 | 37.2 | 35.5 | 34.1 | 33.0 | 32.5 | |

| 39.1 | 71.0 | 35.5 | 41.2 | 57.3 | 84.0 | 83.7 | 80.5 | 77.8 | 74.6 | 70.9 | 67.6 | |

| 44.0 | 53.4 | 36.5 | 46.4 | 53.1 | 50.4 | 51.3 | 54.2 | 50.6 | 48.9 | 48.2 | 47.4 | |

| 18.9 | 35.6 | 22.5 | 15.9 | 29.8 | 39.2 | 37.8 | 37.3 | 35.2 | 35.0 | 36.0 | 38.4 | |

| 46.3 | 40.1 | 50.7 | 49.1 | 38.6 | 45.5 | 44.2 | 42.4 | 40.8 | 38.8 | 34.4 | 32.4 | |

| 26.7 | 41.7 | 17.0 | 27.9 | 37.4 | 42.2 | 40.0 | 36.8 | 34.7 | 32.7 | 31.7 | 31.1 | |

| 61.9 | 78.6 | 55.3 | 60.5 | 80.2 | 76.7 | 76.7 | 76.0 | 73.4 | 70.8 | 69.2 | 67.7 | |

| 41.6 | 82.5 | 37.0 | 39.8 | 75.2 | 87.0 | 87.9 | 87.9 | 87.1 | 86.8 | 85.1 | 84.2 | |

| 61.3 | 84.5 | 60.1 | 61.5 | 79.1 | 88.3 | 86.2 | 85.0 | 83.3 | 81.5 | 80.2 | 78.8 | |

| 57.6 | 59.1 | 63.8 | 58.1 | 54.1 | 66.1 | 68.7 | 68.7 | 66.9 | 68.1 | 66.0 | 64.0 | |

| 41.7 | 85.7 | 37.2 | 24.5 | 85.4 | 79.7 | 65.8 | 51.9 | 42.5 | 40.6 | 38.3 | 36.2 | |

| – | 51.4 | – | 38.2 | 40.7 | 59.9 | 66.2 | 64.4 | 64.2 | 70.6 | 68.4 | 64.5 | |

| 33.7 | 31.5 | 45.6 | 36.7 | 24.1 | 38.1 | 38.1 | 39.9 | 39.5 | 40.5 | 43.2 | 44.0 | |

| 70.6 | 53.8 | 224.8 | 46.2 | 48.9 | 65.4 | 70.7 | 68.6 | 60.1 | 54.5 | 50.9 | 48.0 | |

| 53.9 | 33.9 | 51.6 | 50.8 | 40.1 | 28.8 | 27.6 | 28.3 | 28.3 | 31.1 | 30.9 | 29.3 | |

| 53.1 | 43.2 | 54.5 | 57.0 | 42.8 | 43.3 | 43.3 | 42.5 | 41.2 | 40.0 | 39.0 | 38.3 | |

| 40.2 | 31.2 | 28.0 | 41.3 | 41.9 | 27.2 | 31.7 | 35.3 | 36.0 | 39.3 | 32.1 | 30.7 | |

| 64.2 | 101.6 | 53.2 | 65.6 | 95.5 | 104.6 | 104.8 | 106.8 | 105.2 | 107.4 | 107.8 | 136.6 | |

| 168.9 | 225.5 | 137.9 | 176.8 | 207.9 | 236,1 | 231.6 | 236.7 | 234.8 | 236,1 | 236,1 | 236.3 |

Household deficit in industrialized countries [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

The debt of the overall state is usually caused by deficits in public households. The following table reproduces a list of the Austria Chamber of Commerce (as of May 2019, Source EU Commission). Italics figures are forecasts.

Since the beginning of Covid 19 pandemic, many industrialized countries have significantly increased their 2020 public debt. [sixty one]

Eurozone (19)

European Union (28), but not euro zone (19)

not European Union (28)

more than -3.0% to -3.0% to -1.5% ≥0% (no deficit)

| Land | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | two thousand and thirteen | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 * | 2019 * | 2020 * |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| -4.0 | -4.2 | -4.2 | -3,1 | -3,1 | -2,4 | -2,4 | -0.8 | -0,7 | -1.3 | -1.5 | |

| -3,1 | -2.0 | -0.3 | -0.4 | -5.5 | -1,7 | 0.1 | 1.2 | 2.0 | 0.8 | 1.0 | |

| -2,7 | -2,1 | -3.5 | -1.2 | 1.1 | -1.3 | -0,1 | 1.4 | 0.5 | 0.6 | -0,1 | |

| -4.2 | -1.0 | 0.0 | -0,1 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 1.0 | 0.8 | |

| 0.2 | 1.2 | -0.3 | -0.2 | 0.7 | 0.1 | -0.3 | -0.4 | -0.6 | -0.3 | -0.5 | |

| -2.6 | -1.0 | -2,2 | -2.6 | -3,2 | -2,8 | -1,7 | -0.8 | -0,7 | -0.4 | -0.2 | |

| -6,9 | -5,2 | -5.0 | -4,1 | -3,9 | -3.6 | -3.5 | -2,8 | -2.5 | -3,1 | -2,2 | |

| -11,2 | -10.3 | -8,9 | -13.2 | -3.6 | -5.6 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 1.1 | 0.5 | -0,1 | |

| -32,1 | -12.8 | -8,1 | -6,2 | -3.6 | -1.9 | -0,7 | -0.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.3 | |

| -4.2 | -3,7 | -2,9 | -2,9 | -3.0 | -2.6 | -2.5 | -2,4 | -2,1 | -2.5 | -3.5 | |

| -6.3 | -7.9 | -5.3 | -5.3 | -5,1 | -3,2 | -1.0 | 0.8 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.5 | |

| -8.6 | -4.3 | -1.2 | -1.2 | -1,4 | -1,4 | 0.1 | -0.6 | -1.0 | -0.6 | -0.6 | |

| -6,9 | -8,9 | -3,1 | -2.6 | -0.6 | -0.3 | 0.2 | 0.5 | 0.7 | 0.3 | 0.0 | |

| -0,7 | 0.5 | 0.3 | 1.0 | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 1.4 | 2.4 | 1.4 | 1.1 | |

| -2,4 | -2,4 | -3.5 | -2,4 | -1,7 | -1.0 | 0.9 | 3.4 | 2.0 | 1.1 | 0.9 | |

| -5,2 | -4,4 | -3,9 | -2,9 | -2,2 | -2.0 | 0.0 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 1.4 | 0.8 | |

| -4,4 | -2.6 | -2,2 | -2.0 | -2,7 | -1.0 | -1.6 | -0.8 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.2 | |

| -7.3 | -4.8 | -3,7 | -4,1 | -3,7 | -2,7 | -2,2 | -1.5 | -0.4 | -1.6 | -1,4 | |

| -11,2 | -7,4 | -5,7 | -4.8 | -7.2 | -4,4 | -2.0 | -3.0 | -0.5 | -0.4 | -0,1 | |

| -6,9 | -5,4 | -3,7 | -2,2 | -1.3 | -0,7 | -2,7 | -2,7 | -3.0 | -3.5 | -4,7 | |

| 0.0 | -0.2 | -1.0 | -1,4 | -1.6 | 0.0 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 0.9 | 0.4 | 0.4 | |

| -7.5 | -4.3 | -4.3 | -2,7 | -2,7 | -2.6 | -2,2 | -0.8 | -0,7 | -0.5 | -0.6 | |

| -5.6 | -6,7 | -4.0 | -14.7 | -5.5 | -2,8 | -1.9 | 0.0 | 0.7 | 0.7 | 0.9 | |

| -9,4 | -9.6 | -10.5 | -7.0 | -6,0 | -5.3 | -4.5 | -3,1 | -2.5 | -2.3 | -2.0 | |

| -4.2 | -2,7 | -3,9 | -1.2 | -2,1 | -0.6 | 0.7 | 1.6 | 0.9 | 0.2 | -0.2 | |

| -4.5 | -5,4 | -2,4 | -2.6 | -2.6 | -1.9 | -1.6 | -2,2 | -2,2 | -1.8 | -1.6 | |

| -9.3 | -7.5 | -8,1 | -5.3 | -5.3 | -4.2 | -2,9 | -1.9 | -1.5 | -1.5 | -1.2 | |

| -4,7 | -5,7 | -5.6 | -5,1 | -9.0 | -1.3 | 0.3 | 1.8 | -4.8 | 3.0 | 2.8 | |

| Eurozone (19) | -6,2 | -4.2 | -3,7 | -3,1 | -2.5 | -2.0 | -1.6 | -1.0 | -0.5 | -0.9 | -0.9 |

| -6,4 | -4.6 | -4.3 | -3.3 | -2,9 | -2.3 | -1,7 | -1.0 | -0.6 | -1.0 | -1.0 | |

| -12,4 | -11.0 | -9.2 | -5,8 | -5,2 | -4.6 | -5.3 | -4,1 | -6,4 | -6.5 | -6,4 | |

| -9,1 | -9,1 | -8.3 | -7.6 | -5,4 | -3.6 | -3.5 | -3.0 | -2,9 | -2,8 | -2.5 |

State debt in developing countries [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

State debt and ratings [ Edit | Edit the source text ]

The probability of repayment of a country’s surrounding government bonds is expressed in its creditworthiness or creditworthiness. In the event of high public debt, the probability of repayment can decrease. To classify the debt of the debt of a state as relatively high or low, there are several number of school thinking. A number of developed countries are classified by private international rating agencies as very creditworthy because their economic output expressed in gross national product is considered a debt adequate. Some industrialized countries therefore receive the highest possible rating code AAA (Moody’s), AAA (Standard & Poor’s) and AAA (FITCH Ratings) for their government bonds. But here, too, due to partly excessive debt policy and possibly less dynamic economic output, downgrades of the rating can threaten.

In particular, the debt relief that the debt sees in relation to gross domestic product or state revenue is examined. Delyibility is just still available when the following criteria can be proven:

For developing countries, debt admission is made more difficult in addition to the tendency to be less than less than less than the credit.

- His Apel: State without measure. Financial policy in dead end . Econ, Düsseldorf/Munich 1997, ISBN 3-430-11066-1.

- Horst Böttcher: Mühlsteine. State debt and interest burden . Services, Bad Soden 1996, ISBN 3-9804200-0-0.

- Heiner Flassbeck: Ten myths of the crisis. Suhrkamp Verlag, Berlin 2012, ISBN 978-3-518-06220-3.

- David Graeber: Debt: The First 5,000 Years , Melville House 2011, ISBN 978-1-933633-86-2.

- Friedrich Halstenberg: State debt. A daring financial strategy endangers our community . Plain Text Verlag, 2001, ISBN 3-88474-966-8.

- Kai A. Konrad/Holger Zschäpitz: Debt without atonement. Why the crash of state finances affects us all. C. H. Beck, Munich 2010, ISBN 978-3-406-60688-5.

- Ralf Kronberger: State debt (crisis) (PDF) , Working Group for Economics and School, Vienna 2012, ISBN 978-3-9502430-8-6.

- ↑ Eurostat, State debt level as a percentage of gross domestic product . The relevant definitions contain the Council Ordinance 479/2010, changed by the Council Ordinance 679/2010.

- ↑ a b Federal Office of Statistics: Details for finance, taxes, public service

- ↑ Federal Ministry of Finance, Budget bill and financial statements by the federal government for the 2006 financial year , Annual accounts 2006, p. 1.

- ↑ However, an alleged cicero quote, which is often used as a historical proof of the demand for a debt-free state budget, is an invention. The supposed quote is: “The state budget must be balanced. Public debts have to be broken down, … The support to foreign governments must be reduced if the state is not to go bankrupt. People should learn to work again instead of living on public account ”( Wikiquote, Cicero: Incorrect attributed ). Cited z. B. at Bodo Leibinger/Reinhard Müller/Herbert Wiesner, Public finance , 2014, S. We Or in the FAZ of December 28, 1990, p. 3. It is actually a job from a fictional cicero novel by Taylor Cadwell: A Pillar of Iron , Doubleday, 1965, ch. 51, p. 483 (German: A column from ore , 1965). S. tulliana.eu .

- ↑ Alfred Manes, State bankrotte , 1919, S. 26.

- ↑ Institute for Bank History Research/Ernst Klein, German banking history: From the beginning to the end of the old empire (1806) , Band 1, 1982, S. 73.

- ↑ Gerald Braunberger/Benedikt Fehr, Crash: Financial crises yesterday and today , 2008, S. 18.

- ↑ Alfred Manes, State bankrotte , 1919, S. 55.

- ↑ Fernand Brudgel, Social history of the 15th to 18th centuries , Band III, 1985, S. 338 f.

- ↑ Jacob Peter Mayer, Fundamental Studies on Jean Bodin , 1979, S. 33.

- ↑ Jean-François Melon de Pradou, Financial Economists Du 18ME Siecle , 1734, S. 95.

- ↑ David Hume, Essay on Public Credit , 1752, S. 360 f.

- ↑ Adam Smith, The prosperity of the nations , Book V, Chapter 3: On Public Debts, 1776/1974, p. 798.

- ↑ Adam Smith, The prosperity of the nations , Book V, Chapter 3: On Public Debts, 1776/1974, p. 911.

- ↑ Thomas Jefferson/Lyman Henry Butterfield/Charles T. Cullen, The Papers of Thomas Jefferson: March 1789 to 30 November 1789 , 1958, S. 393.

- ↑ Immanuel Kant, For eternal peace , 1795, S. 7 f.

- ↑ David Ricardo, Principles of political economy , Band 1, 1817/1959, S. 233 ff.

- ↑ David Ricardo, Principles of political economy , Band 1, 1817/1959, S. 233 ff.

- ↑ Alfred Manes, State bankrotte , 1919, S. 57.

- ↑ Friedrich List, The national system of political economy. S. 265.

- ↑ Karl Marx, The capital , Band 1, 1867, S. 782 f.

- ↑ Thomas Piketty: The capital in the 21st century . 1st edition in C.H. Beck Paperback. Munich 2016, ISBN 978-3-406-68865-2, S. 175 .

- ↑ Lorenz von Stein, Textbook of financial science , 1875, S. 716.

- ↑ Adolph Wagner, Financial science , 1890, S. 229.

- ↑ Peter Lippert, State debt in Germany, Italy and Greece , 2014, S. 36.

- ↑ Ernst Löschner, Sovereign risks and international debt , 1983, S. 44 ff.

- ↑ John Maynard Keynes, The General Theory of Employment, Interest, And Money , 1936, S. 211.

- ↑ a b Carmen Reinhart/Kenneth Rogoff, This Time is different , 2009, S. 232.

- ↑ Pierro Sraffa (ed.): David Ricardo: The Works and Correspondance , Band IV: 1815–1823 , 1951, S. 197.

- ↑ Christoph Braunschweig/Bernhard Pichler, The credit economy , 2018, S. 107.

- ↑ Kjell Hausken/Mthuli NCUBE, Quantitative Easing and Its Impact in the US, Japan, the UK and Europe , Springer Science & Business Media, 2013, ISBN 978-1-4614-9646-5, S. 1.

- ↑ Gareth D. Myles: Public Economics. Cambridge University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-521-49769-5, S. 486 ff.

- ↑ Hugh Dalton: Principles of Public Finance. Allied publishers, 1997, 4th edition, ISBN 978-81-7023-133-2, p. 180 ff.

- ↑ A regulation can be found at the Federal Ministry of Justice: “Ordinance on the procedure for determining the economic component in accordance with Section 5 of Article 115 law (Article 115 Regulation-Art115V)”

- ↑ Federal Ministry of Finance: Public finances – production potential and economic components – calculation results and data bases from April 24, 2012.

- ↑ See Achim Truger, Henner Will, Institute for Macroeconomics and Economic Research (January 2012): “Design-prone and pro-cyclical: German debt brake in detail analysis”

- ↑ Franz Schuster: Europe in change , 2013, S. 89.

- ↑ Handelsblatt 19. May 2010: “Hidden debts – the state lacks trillions” ; NZZ, January 25, 2013 “The state debt iceberg”

- ↑ Pascal gamblein / claus jumped, Interest, bonds, loans , 2014, S. 25.

- ↑ Beat market – Germany borrowed money on negative interest rates , Do online, 9. januar 2012.

- ↑ Schäuble makes money with debt making , Handelsblatt Online, July 18, 2012.

- ↑ Yeva Nersisyan, L. Randall Wray: Review: This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly. By Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff . In: Challenge . Band 54 , No. first , 1. January 2011, ISSN 0577-5132 , S. 113–120 , doi: 10,2753/0577-5132540107 .

- ↑ Hubert Beyerle: New thinker (61): Randall Wray and the myth of debt trap ( Memento from July 6, 2011 in Internet Archive ). In: Financial Times Deutschland. July 5, 2011.

- ↑ Thomas Herndon, Michael Ash, Robert Pollin: Does high public debt consistently stifle economic growth? A critique of Reinhart and Rogoff . In: Cambridge Journal of Economics . Band 38 , No. 2 , March 1, 2014, ISSN 0309-166X , S. 257–279 , doi: 10.1093/AJCY/BET075 .

- ↑ Alexander Ruth: Reinhart, Rogoff… and Herndon: The student who caught out the profs. (No longer available online.) BBC News Magazine, April 19, 2013, archived from Original am 25. June 2013 ; Retrieved on July 4, 2013 .

- ↑ Peter Bofinger: Basic features of economics. Pearson Studium, 2010, ISBN 978-3-8273-7354-0, S. 8 ff.

- ↑ “Sink flight returns”, Handelsblatt August 5, 2010

- ↑ Wilhelm Lautenbach: About credit and production. Frankfurt 1937. (first published in 1936 in the quarterly booklet: The business curve. Issue III. ) S. 18:

“How does the credit device work if the state finances large expenses through loan? Where do the funds come from? ”

“Most who ask the question, and there are by no means only laypersons, have the idea as if there was any limited stock of money or credit. With this idea, the concerned question usually links whether the state does not cover the loan to the economy due to its loan claims. In truth, however, it is exactly the opposite. If the state takes a loan on a large scale, the whole credit industry is loosened up. The money and credit markets become fluid, the entrepreneurs become liquid, their bank loans decrease, business deposits are increasing […]. ” - ↑ Olivier Blanchard, Gerhard Illing: Macroeconomics. (5th edition) Munich 2009. ( online ) S. 26.

- ↑ German Bundesbank: Money and monetary policy , S. 146.

- ↑ Carsten Germis: The world improvers: the Japanese Keynes . In: Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung . 26. August 2013, ISSN 0174-4909 ( faz.net [accessed on April 23, 2016]).

- ↑ Hans Strich: New credit policy. Stuttgart and Berlin 1936, pp. 73–95:

“You cannot leave it to the well -qualified banking management whether it wants to impose the victims of deflation to the national economy or reduce the change of exchange. In such questions of fate, only the government, which also has to bear the social and political consequences, can make the decision. The impact and success of the general economic policy depends on credit policy today … ” - ↑ Wolfgang Stützel: Economic Salden Mechanics Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2011, Nachdr. The 2nd ed., Tübingen, Mohr, 1978, p. 86.

- ↑ John Maynard Keynes: The Economic Consequences of Mr. Churchill. In: Essays in Persuasion. W. W. Norton & Company, 1991, S. 259.

- ↑ John Maynard Keynes: The Return to the Gold Standard. In: Essays in Persuasion. W. W. Norton & Company, 1991, S. 208.

- ↑ John Maynard Keynes: The Great Slump of 1930. In: Essays in Persuasion. W. W. Norton & Company, 1991, S. 146.

- ↑ John Maynard Keynes: General theory of employment, interest and money. Duncker & Humblot, Munich/Leipzig 1936, p. 268.

- ↑ Public gross debt. Eurostat, Retrieved on May 11, 2019 .

- ↑ Largest debt mountain in the Federal Republic. ( Memento from March 13, 2010 in Internet Archive ) Tagesschau, March 11, 2010.

- ↑ Public debt: state debt rate (debt level of the overall state in% of GDP). (PDF) Economic Chamber of Austria (WKO), May 2019, accessed on June 27, 2019 .

- ↑ For example, the British government started 259.6 billion pounds of new debts in the first half of 2020 ( Those )

- ↑ Public budgets: surplus/deficit of the overall state in% of GDP: absolute values. (PDF) Economic Chamber of Austria (WKO), May 2019, accessed on June 27, 2019 .

- ↑ IMF and World Bank: Debt Sustainability Analysis for the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries (PDF; 1.5 MB), January 1996, p. 2 (p. 4 in PDF)

Recent Comments