Izates II — Wikipedia

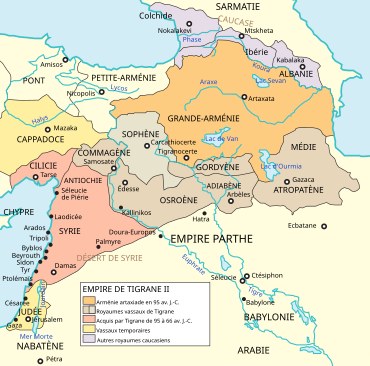

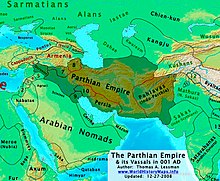

Izatès II or Izatès bar Monobaze (also known as Izate, Izaatès or Izaat; v.1 – v. 57) was a king of Adiabena [ first ] , a theoretically vassal kingdom of the kingdom of Armenia, but in fact very strongly autonomous ( The borders of this kingdom correspond roughly to the territories of the Kurds today ). It was also a proselyte of Judaism. According to Flavius Josephus, Izatès II was one of the sons of Queen Hélène and Monobaze I is . The Talmud specifies that Queen Hélène d’Adiabène had seven sons.

Conversion to Judaism [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

During his youth, the future Izatès II was sent by his father to the court of King Abenerigos (or Abinerglo) [ N 1 ] In the Courtmental demances (ourax Spagis) (Nira Spressage) (The leader of the Malian demands’ [ N 2 ] , capital of the kingdom of Characene also known as Messene [ 2 ] .

“Highly fearing that the hatred of his brothers would be woe, [Monobaze I is ] sent him, after having made him big presents, to Abenerigos, king of the Spasinès camp to whom he entrusted his security. Abenerigos received the young man eagerly, showed a great affection, gave him for woman his daughter named Symacho and gratified him from a country which would bring him big income [ 3 ] , [ 4 ] . »

While he was in Spasinès, Izatès got to know a rich Jewish merchant named Ananias, also Rabbi who practiced proselytism [ 2 ] militant and effective for his religion for the upper classes of the countries of the region [ 5 ] . He familiar with the principles of Jewish religion, which looked at him [ first ] . Izatès married Symacho the daughter of King Abenerigos [ 6 ] which had also been converted to Judaism by the proselytism of Ananias [ 2 ] , [ 5 ] .

“Ananias, who had access to the royal gynecence, told women to worship God according to the national custom of the Jews. Thanks to them he made himself known to Izatès and the persuada too [ 7 ] , [ 5 ] , [ 4 ] . »

Without him knowing, the mother of Izatès, Hélène d’Adiabène, had almost converted to Judaism at the same time, but independently of him [ 2 ] , [ first ] , since they then lived in two different countries. When he returned home to get on the throne on the death of his father, Izatès discovered the conversion of his mother and expressed the intention of adopting Judaism. He even wanted to submit to circumcision. However, he was dissuaded by both his master Ananias and his mother [ 2 ] , [ 5 ] , [ first ] .

“Indeed, he was king,” she said, “he would alienate his subjects very much if they learned that he wanted to adopt foreign customs and opposed to theirs, because they would not bear to have a Jewish king [ 8 ] . »

But finally, he was still circumcised, after being convinced by Eléazar another Jewish Rabbi, originally from Galileo [ 2 ] , [ 5 ] , [ first ] .

“[Ananias and Hélène] were immediately seized with stupor and a great fear, saying that, if the thing was known, the king could be driven out of power, because his subjects would not bear to be governed by A zealous of foreign customs, and that they themselves would be in danger, because the responsibility would be rejected on them. But God prevented their fears from realizing [ 8 ] , [ 5 ] . »

When several parents of King Izatès II, including his brother Monobaze, openly recognized their conversion to Judaism, some nobles of Adiabena then conspired to dismiss him. They pay in particular Abia, an Arab king, then after his failure vologists I is , King of the Parthians, so that they were warning the war at King Izatès II. But he comes out victorious from each confrontations.

Lord of Carrhes [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

His father gave him the country of Carrhes (south of Edessa, on the Turkish-Syrian border), probably after the death of King Abenerigos, around 21.

“Monobaze was already old and understood that he had little time to live; So he wanted to see his son before he died. So he brought him up, kissed him with great affection and gave him the country called Carrhes [ N 3 ] This land is very suitable for producing amome in abundance (a plant with which ointments were made). It is also there that the remains of the ark are where, it is said, Noah escaped from the deluge, remains which, until today, are shown to those who want to see them. Izatès therefore lived in this region until the death of his father [ 9 ] . »

This gift from the Carrhes region by his father was apparently the way for Monobaze I is to formalize the designation of Izatès as his successor. This gift by Monobaze I is Also shows that this territory which belonged to the Osroen at the time of the Battle of Carrhes (-53) had passed under the control of the Kingdom of Adiaben [ N 4 ] .

As for Ananias who had converted Izatès and his wife to Judaism, the future king took him with him.

“[When Izatès] was recalled by his father in Adiaben, Ananias accompanied him, obeying his pressing solicitations [ 7 ] . »

Accession to the throne [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

On the death of his father Monobaze I is , her mother Hélène had to manage a difficult transition during which she managed that her son Izatès was recognized as a legitimate successor, while saving the life of her other sons [ 2 ] . The dynastic transmission was made by designation of his successor by the king still alive. Monobaze I is had appointed Izatès to succeed him, although his eldest son was Monobaze who succeeds Izatès under the name of Monobaze II. To justify your Monobaze choice I is invoked a divine voice that would have spoken to him when Hélène was pregnant with Izatès.

On the death of his father, Izatès still lived in the country of Carrhes. The greats of the kingdom of Adiaben accepted that Izatès succeeded his father, but asked that his other brothers be executed. It was indeed a common practice in the region to avoid wars which could result from dynastic conflicts between brothers [ 2 ] . Hélène managed to save the life of her other sons while delaying, but was forced to put her sons in prison, however, like those of the other wives of Monobaze I is . However, she obtained that killing could only be decided by Izatès, when it would have returned. She also obtained being able to “establish temporarily as a regent of the kingdom” Monobaze [ N 5 ] , his eldest son [ 2 ] , [ 9 ] . Izatès “returned, quickly when he learned the death of his father and succeeded his brother Monobaze, who gave him power [ 2 ] , [ 9 ] . »

“When Izatès had taken royalty and arriving in adiaben he saw his brothers and other chained parents, he was unhappy with what had happened. Watching as ungodly to kill them or keep them chained, but deeming dangerous to leave them free with him as they remember the offenses received, he sent some as hostages to Rome near the Emperor Claude with their children and He sent the others under a similar pretext to Artabane the Parthian [ 7 ] , [ 4 ] . »

This hostage status seems to have only concerned the sons of other women in Monobaze I is ; Indeed the presence of the sons of Hélène (therefore brothers of Izatès) is mentioned several times by Flavius Josephus in Judea and in Jerusalem in the following years. Flavius Josephus says that Hélène and his sons had a palace in Jerusalem. The ruins of it were also discovered in 2007.

Curiously enough, after the conversions of Hélène and Izatès and his accession to power, all her other brothers and all of her parents seem to have also converted to Judaism simultaneously. This belonging to Judaism is more publicly revealed. When several parents of Izatès openly recognized their conversion to Judaism, some nobles of Adiabena secretly wrote to Abia, an Arab king, “by promising him a large sum of money” to declare war in Izatès. But Izatès defeats his enemy, who committed suicide from despair. Towards the end of the reign of Izatès, the nobles, dissatisfied with his conversion, conspire again with Vologèse I is , King of the Parthians, but at the last moment he is prevented from putting his plan for execution, because when he sets out to invade the Adiabena, an army of Daces and Scythians entered by Parthie and he must to face [ ten ] .

Kingdom expansion [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

At an undetermined time, probably located in the 1920s or 30s, the King of the Parthe Artaban III Empire was in a mound to a terrible sling of his nobles who chose a king, secretly supported by the Romans. He asks Izatès to accept that he takes refuge in his home [ ten ] .

“So he arrived at Izatès, surrounded by about a thousand parents and servants, and met him on the way [ 11 ] . »

Izatès hastens to accept [ ten ] By reserving for his guest all the honors due to a “king of kings”. This attitude propels him to the level of the “king of kings”.

“Take courage:” he said, “O king,” and that the present calamity does not upset you as if it were irreparable: your grief will quickly change in joy. You will find in me a better friend and ally than you hoped; Indeed, where I will reinstall you in the kingdom of Parthians, or I will lose mine [ 11 ] . »

Izatès is then so respected that he manages to arise as a arbitrator between King Parthe Artaban III, his nobles in rebellion [ first ] , [ ten ] and the usurper called Cinname [ 2 ] . Thanks to the help of Izatès, Artaban found his throne (v. 36). In thanks, he gave Izatès some gifts, including the city of Nisibe and his region [ ten ] , [ N 6 ] .

“[Artaban] was not thankless for the services he had received and he rewarded Izatès with the greatest honors: he allowed him to wear the right tiara and to sleep in a golden bed, while this honor and This badge is reserved only for the kings of the Parthians. He also gave him a large fertile country which he detached from the possessions of the King of Armenia. This country is called NisiBis. The Macedonians once found the city of Antioch which they named Epimygdonian [ 7 ] . »

Emancipation [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

While several wars are triggered in the surrounding countries, Izatès manages to maintain his kingdom away from these conflicts. Although he is theoretically vassal of the Parthian Empire, he observed a strict neutrality, when in 34, at the death of Artaxias III of Armenia, the King Parthe Artaban III (king of 12 to 38), tries to Put his son Arsace on the throne of Armenia, which was a Roman protectorate since 65 BC. This action triggered two years of war, during which the Romans aroused the invasion of Armenia by Sarmatian forces [ N 7 ] , ibères [ N 8 ] and Albanian (Daghestan), and various conspiracies so that the noble Parthians deposit Artaban III and replace it with a king favorable to the Romans. Throughout this troubled period, Adiaben did not make any hostile act towards the Romans and it can be assumed that agreements had been made between Izatès and Lucius Vitellius, the Roman legate of Syria. The Romans manage to install Mithridate of Armenia on the throne and Artaban III almost lost his own [ twelfth ] , [ 13 ] .

At the end of this crisis, the adiaben is no longer a vassal of the Parthians but of the Kingdom of Armenia. It has in fact gained wider autonomy, especially because on the death of Tiberius (March 37), Caligula’s madness comes to compromise everything for the Romans. Without reason, the emperor summons Mithridate from Armenia to Rome and shoes him from his royalty (37). The Parthians do not fail to take advantage of this fault to reoccupy Armenia, and the Adiaben takes the opportunity to assert its autonomy even more by rejecting its Armenian vassality, which in fact was hardly more than a year old [ 14 ] .

Neutrality towards the Roman Empires and Parthian [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

But a first cause of friction was born after the death of the Parthian monarch:

“Artabane died, leaving the throne to her Vardan son. He went to Izatès and tried to convince him, as he was about to wage war with the Romans, ally with him and provide him with his support. But he did not convince him, because Izatès knew the power and the fortune of the Romans and believed the impossible company. […] The Parthian, irritated by this, immediately declared war in Izatès; But he did not remove any profit from this business, because God destroys all his hopes. Indeed, when the Parthians learned Vardane’s projects and his decision to fight the Romans, they got rid of him and gave power to his brother Cotardès [ N 9 ] , [ 8 ] , [ 4 ] . »

Around 47-49, after the death of Vardanès I is , Emperor Claude supports the Parthe party who tries to bring Meherdatès to power against King Gotarzès II [ ten ] . Cassius, the Governor of Syria, and Carénès, the main partisan Parthe of Merherdatès, rally to Méherdatès Izatès and Arabic Abgar V Ukomo Bar Ma’nu (13-50), king of Edessa. But according to Richard Gottheil, “Izatès plays a double game, while he secretly took sides for Gotarzès [ ten ] . It is probably the same for his probable Abgar V. after having lost too much time in Edessa, they begin to movement towards the Adiaben via Armenia, while winter is approaching.

“They pass the tiger and cross the Adiabénie, whose king Izatès, apparently ally of meherdate, secretly leaned for Gotarzès and served him in better faith [ 15 ] . »

But Gotarzès takes refuge behind the Corma river and refuses the fight, judging his army insufficient.

“He delayed, changed positions, sent corrupters to buy betrayal in the enemy ranks. Soon Izatès, and then acbare, withdrew with the Adiabenians and the Arabs: this is the inconstancy of these peoples [ 16 ] . »

Merherdatès, Carénès and Cassius still face Gotarzès and are defeated.

Benefactor of the Jewish people [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

“Hélène, the king of the king, saw that peace reigned in the kingdom and that her son was happy and even envied by all, even among foreign peoples, thanks to divine Providence. She had the desire to go to the city of Jerusalem to bow down before the temple of God, famous in the whole universe, and offer sacrifices of thanksgiving, and asked for permission from her son. Izatès agreed with the greatest eagerness at the request of his mother, made great preparations for his trip and even gave him a very large amount of money. So she went down to the city of Jerusalem, not without her son having accompanied her very far [ 17 ] . »

From her accession to the throne, Hélène and her sons seem to have spent a good part of their lives in Judea [ 2 ] . “Izatès sent five of his sons to Jerusalem to have them educated in the religion and the language of Judeans [ 2 ] . »Flavius Josephus mentions that Hélène had a palace in Jerusalem [ 2 ] . According to rabbinical sources, her mother Queen Hélène also had a residence in Lydda (LOD). Monobaze, the older brother, also had a palace in Jerusalem [ 2 ] . According to Heinrich Graetz, the granddaughter of Hélène d’Adiabène, the princess climbed, had built another in the Ophel district [ 2 ] .

Flavius Josephe unfortunately does not give the details of the names of the sons and parents present with Queen Hélène in any of the episodes where she appears. He repeatedly mentions Hélène d’Adiabene accompanied by his sons and specifies that they were seven. The Jews of Judea, Galilee and the Samaritans seem to have devoted a quasi devotion to Queen Hélène, despite aspects of her personality, difficult to accept for a Jew of I is century [ 2 ] .

Hélène and her sons are famous for their generosity and the support they provided in all circumstances to the Jewish people of Judea and Galileo. During a famine in Jerusalem, Hélène sent ships to seek wheat or other cereals to Alexandria and look for dry figs to Cyprus and had them distributed to the victims of the famine [ 2 ] , [ 18 ] . In the Talmud (BB 11A), this action is put to the credit of Monbaz , without more precision. This reference to Monbaz is sometimes considered to designate not the monarch but the dynasty [ 19 ] and therefore the two sovereigns and their children [ N 10 ] . This great famine took place while Tiberius Julius Alexander was a prosecutor of Judea, therefore around 46-48 [ 20 ] . At the time of famine, King Monobaze I is has been dead for a long time and it is izate that reigns at that time.

-

- ‘ A fowl succventus Tiberius Alexander ( The nephew of Philon of Alexandria ), son of Alexander, the former Alabarque of Alexandria […] It was under the latter that Arriva in Judea the Grande Distente where Queen Hélène bought wheat in Egypt at Grand Prix to distribute it to the indigent , as I said above [ 21 ] . »

Death and succession [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

According to Heinrich Graetz, Izatès died around 55, at the age of 55 [ 2 ] . Hélène, her mother, seems to have been deeply affected by her death whose circumstances are not known, and also survives him for a short time.

“A little later Izatès died, after having finished his fifty-fifth year and after twenty-four years of reign (v. 34–58), leaving twenty-four sons and twenty-four girls. The succession to the throne was to return according to his orders to his brother Monobaze, as a reward for the loyalty with which he had kept his power in his absence, after the death of their father [ 22 ] , [ first ] . »

Monobaze II actually succeeds his brother Izatès. He sends her remains and those of Queen Hélène to Jerusalem so that they are buried there [ first ] .

“Monobaze sent [the] bones [of Hélène] and those of her brother to Jerusalem and made them bury in the three pyramids that his mother had built at three stages from the city [ 22 ] . »

These catacombs are now called the tomb of kings [ N 11 ] .

Izatès had several women. When he died, Flavius Josephe indicates that he had “twenty-four sons and twenty-four daughters” [ 22 ] , [ first ] .

Notes [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

- Abenerigos (or Abinerglo after one of his tetradrachms) reigned on Charax Spasinu from 5 to 21 AD. AD ( cf. Georges Mathieu)

- Charax Spasinu or Spasinès was the capital of the kingdom of Characène, also known as Mesene (חבל ימא), a kingdom dependent on the Parthe Empire located at the top of the Persian Gulf.

- Carrhes in Mesopotamia (the old charan; cf. Besnier, lexicon of ancient geography) when later Izatès receives possession of Nisibe, this acquisition must ensure its communications between Adiaben and Mesopotamia. (Georges Mathieu)

- In the first century, under Monobaze I is , we note that several other territories which belonged to the Osrone at the time of Pompey had also passed under the control of the kingdom of Adiaben. This is the case of Singara, but also of the region of the Khabour river ( Chaboras ) which depended on the bone in the time of Tigrane II of Armenia. This movement of territories from bone to the adiaben will be further reinforced by the donation of Nisibe by Artaban III. In addition, the cordotene had been attached to the adiaben after the invasion of Armenia by Pompey, in -63. Some criticisms believe that at that time, the kings of Adiaben may also control Hatra ( cf. (in) Javier Teixidor, The Kingdom of Adiabene and Hatra , Berytus , 17, 1967-1968) (region north of Iraq, near Mosul, also populated by Arabs, close to the Nabatéens). Tacitus mentions that a king of Adiaben had his statue in one of the temples of Hatra, ( cf. JAVIER TEXIDOR, Hatrean notes , p. 96 ).

- Hélène “invests in Monobaze royalty, the king’s eldest son, imposing the diadem for him and giving him the ring bearing the seal of her father and what is named in this country Samspsér (it was a scepter bearing the image of the sun) ”; (Flavius Josephus, Judaic antiques , Book XX II – 2.

- It is probably the gift of Nisibe and his region which explains that, according to the book II From the history of Armenia of Moses from Khorène, King Abgar IN Transfers her capital to Édesse from Nisibe where she was before. Abgar’s father IN , Ma’nu Saphul reigned at least on part of the Adiaben and Nisibe was probably part of its territories.

- Called “Alains” (ἀλαοὺς) by Flavius Josephus, Judaic antiques , 18-4, 4

- The “ibères” according to Tacitus and “Ibernes” according to Flavius Josephus belonged to a corresponding kingdom approximately to the southern and eastern parties of the current Georgia

- Gotarzès according to Tacitus, Annales , XI, 8-17.

- In Jewish tradition this interpretation is however disputed by the Rabi Rashi.

- Compare with Ecclesiastical history , Eusebius of Caesarea, II., Ch. 12

References [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

- (in) Richard Gottheil and Isaac Broydé, “Izates” (from Adiabena) , on Jewish Encyclopedia .

- Heinrich Graetz, History of Jews , Chapter XVI-Dispersion of the Judaic Nation and dissemination of its doctrine-(40-49)

- Flavius Joshenphs, Judaic antiques , Book xx II – 1

- See also Heinrich Graetz, on. Cit.

- H. G. Enelow, (in) « Ananias of Adiabene » , on Jewish Encyclopedia .

- Christian Settipani, Our antiquity ancestors : studies of the possibilities of genealogical links between families of antiquity and those of the High Middle European , Éditions Christian, 1991, Paris, p. 80.

- Flavius Joshenphs, Judaic antiques , Book xx II – 3

- Flavius Joshenphs, Judaic antiques , Book xx II – 4

- Flavius Joshenphs, Judaic antiques , Book xx II – 2

- (in) Richard Gottheil “Adiabene” on Jewish Encyclopedia

- Flavius Joshenphs, Judaic antiques , Book 20 3 – 1

- Tacit, Annales , Book VI, from XXXI to XXXVIII

- Flavius Joshenphs, Judaic antiques , 18-4, 4-5

- René Greatly, History of Armenia , Payot, 1984 (ISBN 2-228-13570-4 ) , p. 105.

- Tacit, Annales , Liter 12, § 13.

- Tacit, Annales , Locre XII, § XoIV.

- Flavius Joshenphs, Judaic antiques , Book xx V – 5

- Flavius Josephus, Judaic antiques, book XX II – 5

- Rabbi Nehemiah Brüll, “Year.” i. 76.

- Verse l’and 47, selon Heartrich grazing, on. Cit.

- Flavius Josephus, Judaic antiques book XX V – 2.

- Flavius Joshenphs, Judaic antiques , Book xx IV – 3

- Genealogy of Izatès II , on http://fabpedigree.com

- Primary sources

- Flavius Joshenphs, Judaic antiques , Book XX, from II to IV.

- Flavius Joshenphs, Jews War , Livre we, we – 3.4.

- Moses from Khorène, Book II, Chapters 35-36.

- The Sweay Ata Masam , the Seder ‘Olam Rabbah and the Saler .

- Strabon, Geography , XI, 14.16.

- Tacit, Annales , XV – 1s.

- Talmud de Babylone, Yoma 37, Suk. 2.

- Appien, Mithridatic wars .

- Dion Cassius, Roman history, XL book, 21 – 27; LXVIII book, 17.

- Eusebius of Caesarea, Ecclesiastical history II., Ch. 12.

- Secondary sources

- (in) Michael Marciak , Sophene, Gordyene, and Adiabene : Three Regna Minora of Northern Mesopotamia Between East and West , Suffering, brille, , 580 p. (ISBN 978-90-04-35070-0 , Online presentation ) .

- (in) Michael Marciak , Izates, Helena, and Monobazos of Adiabene : A Study on Literary Traditions and History , Wiesbaden, LSD, , 324 p. (ISBN 978-3-447-10108-0 ) .

- (in) E. Brauer, The Jews of Kurdistan , Wayne State University Press, Detroit, 1993.

- (in) Salomon Grayzel, A History of the Jews , New York, Mentor, 1968.

- (in) Ernst Schürer, The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ , 3 flight., Eddbourg, 1976-1986.

- Heinrich Graetz, History of Jews , on http://www.histoiredesjuifs.com .

- Tertiary sources

- (in) D. Sellwood, «Ad -IABENE» , In Encyclopædia Iranica ( read online )

- (in) M. Seligsohn, “Mayha Charm zuta» , In http://www.jewishencyClopedia.com .

- (in) Richard Gottheil, «Ad -IABENE» , In http://www.jewishencyClopedia.com .

- (in) H. G. Enelow, « Ananias of Adiabene » , on Jewish Encyclopedia , tested on August 14, 2011

- (in) Merchant Kohler, «Agabus» , on Jewish Encyclopedia , tested on August 14, 2011

- (in) Emil G. Hirsch & M. Seligsohn, «Peshiṭta» , In http://www.jewishencyClopedia.com

- (in) Richard Gottheil and Isaac Broydé, « Izates » , on Jewish Encyclopedia , tested on December 26, 2017

- (in) Richard Gotteheil et M. Seligsohn, « Helena » , In Jewish Encyclopedia . Funk and Wagnalls, 1901–1906, who quote:

- Rabbi Nehemiah Brüll, Year. i. 70-78.

- Heinrich Graetz, Gesch. , 3 It is Ed., III. 403-406, 414.

- Schürer, Gesch. , 3 It is Ed., III. 119-122.

Recent Comments