Amarna — Wikipedia

Akhetaton

Amarna ( Tell El-Amarna or El-Amarna [ first ] ) is the archaeological site of the ruins of Akhetaton, the capital built by the Pharaoh Akhenaton around -1360.

The Arabic name of Tell El-Amarna is undoubtedly the contraction of the names of the current village, El-Till, and a nomadic tribe, the Beni Amran, who left the desert at XVIII It is century to settle on the banks of the Nile. Akhetatus means “the horizon of Aton” in ancient Egyptian.

At this location, located between Thebes and Memphis, the high cliffs of the Arabic chain which stand on the right bank of the Nile depart from the river to form a hemicycle of twelve kilometers in length; It is there that in the year 4 of his reign (around -1360) Akhenaton threw the foundations of the city which will be the capital of the Egyptian Empire for a quarter of a century. The city, dedicated to the worship of the single god Aton, was raised quickly in raw bricks and talatatics; Four years after its foundation, it was already inhabited by a large population that is estimated at least twenty thousand people. Border steles delimited the territory of the city. On one of them, the King proclaims that Avon himself had chosen this location because he was a virgin of the presence of any other divinity. When Toutankhamon left Akhetaton to return to Thebes, the city was abandoned, then dismantled by the successors of Akhenaton and covered by the sands.

Akhetaton is the only city in ancient Egypt, of which we have a detailed knowledge, especially because of the fact that it was deserted shortly after Akhenaton’s death, to never be occupied again. However, due to its exceptional character and the conditions under which the city was founded and then abandoned, it is difficult to know to what extent “the horizon of Aton” was representative of Egyptian town planning.

Visited sporadically by travelers and antiquity collectors at XVIII It is century, mapped by the scholars of the Egyptian countryside, the site was explored at XIX It is century by British and German archaeological missions. The German Karl Richard Lepsius copied the inscriptions, the frescoes and the reliefs to which he had access and published them in his Monuments from Egypt and Ethiopia (1849-59) ( Monuments of Egypt and Ethiopia ). Other surveys of the site were carried out between 1891 and 1908 by Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie and Norman de Garis Davies. The publications of these scholars are of great value, because since then the site was regularly vandalized by villagers in search of building materials and sebakh, a natural fertilizer. From 1907 to 1914, the German Orient Society Explore the workshop of the Thoutmès sculptor where she discovered the bust of Néfertiti which has been exposed from the at the Berlin Museum Neues. The excavations were interrupted during the First World War, then resumed in the 1920s. Since 1977, the Egypt Exploration Society (Egypt Exploration Society) proceeds to the systematic study of the site, under the responsibility of Barry J. KEMP, director of excavations and professor at the University of Cambridge.

Chronology of excavations [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

- 1714 – The French Jesuit Claude Sicard describes the first a stele of Amarna [ 2 ] ;

- 1798-1799 – The scholars of Bonaparte establish an Amarna card published in the Description of Egypt (1809 – 1828);

- 1824 – Sir John Gardner Wilkinson explores and cartography the ruins of the ancient city;

- – Jean-François Champollion briefly visits the site [ 3 ] ;

- 1833 – Copist Robert Hay and G. Laver explore the southern tombs and reproduce the reliefs on engravings kept since the British Library;

- 1843-1845-A Prussian expedition led by Karl Richard Lepsius established a topography of Amarna during two twelve-day visits. The plaster drawings and casts that the expedition had made on the scene are published in Monuments from Ægypt and Æthiopia (1849-1859) [ 4 ] ;

- 1881-1882 – Discovery of the tomb of Akhenaton by inhabitants of the region;

- 1887 – Discovery of a deposit of clay tablets engraved in cuneiform: the Letters from Amarna ;

- 1891-1892 – Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie studies the great temple of Aton and the royal palaces among others;

- 1903-1908 – Norman de Garis Davies draws and photographs the tombs and steles of Amarna;

- 1907-1914-A German archaeological mission led by Ludwig Borchardt under the supervision of the German Eastern Society ( German Orient Society ) excavates the north and southern outskirts of the city. She notably discovers the famous bust of Nefertiti, the . The excavations are interrupted by the First World War.

- 1921-1936 – T.E. Depeet, Siro Ronard Wallety, Henri Franc care, where John’s Frierebussen Le Situals;

- 1960s – Excavations are organized regularly by the Supreme Council of Egyptian Antiquities;

- From 1977 – Barry J. Kemp directed the expeditions of Egypt Exploration Society, which became annual;

- 1974-1989 – Geoffrey T. Martin publishes his studies of the hypogeum says the royal tomb in The royal tomb at el-amarna .

The letters of Amarna [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

In 1887, a villager looking for Sebakh on the site discovered a deposit of several hundred tablets from the Royal Archives. These tablets, the Letters from Amarna , are written in cuneiform akkadian, the language of diplomatic relations of the time. For the most part, these are missives exchanged between the royal court and its vassals of the near East as well as its allies then. This discovery is very precious, because it covers exchanges between the chancelleries since the end of the reign of Amenhotep III , attesting once again that a Coregence with his son is more than likely, up to time troubles from the reign of Akhenaton. Thus, they include a series of calls for help launched by the Egyptian vassals in Syro-Palestine, threatened by the Hittite ambitions, and letters addressed “to the Great King, their brother” by the Kings of Babylon, of Assyria And Mittani, which also had to face this rupture of the balance of forces in the region which Pharaoh seems to have been indifferent, however.

Of course, the Letters from Amarna only give an inevitably incomplete overview of this period, but they nevertheless attest to the close ties existing between the royal courses of the region and testify to the intense diplomatic activity which in antiquity already characterized the relationships between the protagonists of the Near East .

The city, located opposite Hermopolis Magna, formed a large set which stretched for almost nine kilometers. The excavations revealed the existence of four palaces, staged from north to south along the Nile. The “north palace of the banks of the river” surrounded by a surrounding wall seems to have been the royal residence, fortified and isolated from the city proper. Further south was a second palace probably built for Kiya, the “great wife loved by the king”. In the center of the city stood the Grand Palais or Official Palais with its many administrative dependencies, its ceremonial courses and its royal pavilion which included a courtroom. Access was practiced in the north and west by two traffic axes which intersect and distribute the various main parts. The northern portal overlooked a large forecourt which preceded the great temple of Aton, while the western access was to give on the Nile and a royal port.

The large avenue which linked the Grand Palais to the two northern palaces, the royal road, undoubtedly the processional path of Akhenaton, divided the palace into two distinct zones: one, west of the avenue, bordering the Nile , more administrative and ceremonial, with its gigantic throne room, and a large courtyard with a monumental kiosk bordered by colossi of kings; the other, in the east, more intimate with the royal apartments, its gardens and its outbuildings. The avenue was spanned by a covered bridge connecting the two parts, and in which was arranged a “window of apparitions”, the very one since which the king covered the gold of the rewards his faithful subjects. On both sides of the official palace were built the large temple, the “residence of ATON in Akhetaton”, a 760 × 270 enclosure m , and the small temple, also devoted to Aton.

On the southern outskirts finally, Marou-Aton was undoubtedly a place of pleasure and meditation, built to satisfy love brought to nature by the royal family: he owned vast gardens, whose king seems to have made a park zoological, as well as several artificial lakes.

The two temples of Aton occupied the center of the city, adjoining the Grand Palais. Unlike the usual Egyptian temples, where we pass from light to the deep shadow of the Holy of Saints, they offered their open-air courses to the rays of the Sun God and their three hundred and sixty-five altars covered with offerings. These sanctuaries were probably designed on the same model as the Gem-Aton ( ATON is found ) of Karnak, partially cleared, which Akhenaton had built at the start of his reign when he still lived in Thebes: they were composed of a hypostyle room and a succession of pylons, giving six major courses with the altars with offerings – unlike the structure of the classic temples where the courses precede the hypostyle rooms. The pylon doors had to include a peculiarity: perhaps the lintels were broken for nothing to hinder the sun to the temple. However, it should be noted that for the architectural details archaeologists are often reduced to hypotheses, each proposing their own, especially as the two temples there are only foundations and representations in the tombs [ 5 ] .

Nevertheless, we can reasonably assume that the architecture of these temples is the same as that which Khenaton wanted for his Heliopolis in the South, Thebes, and he developed it in a masterful way in Akhetaton as he began to a new capital: he is therefore acted with monuments exclusively dedicated to solar light, which links them more to the solar temples of the old empire than to the classic sanctuaries of the new empire. Perhaps we can even detect in this type of architecture Heliopolitan influences, although the Heliopolis site has been as much upset as that of Tell El-Amarna.

With the Grand Palais, the two temples of Aton were the determining element of Akhetaton – his raison d’être, and they thus formed the scene on which was played the life of the royal court, but also the great ritual ceremonies exclusively dedicated to Aton, and exclusively accomplished by the king himself.

Around this vast set spanned without any urban planning the residences of dignitaries, surrounded by more modest houses, which makes Sergio Donadoni say that “The city appears without a premeditated plan […]: near the god the king, near the king the dignitaries of the kingdom, near the dignitaries their auxiliaries – but all this without there are districts fundamentally differentiated by the status of their inhabitants” [ 6 ] . The main interest of this disorderly town planning is to have been preserved at least as to its foundations. Thus we have real plans of Amarnian residences, from the royal palace to the house of the simple servant. These testimonies are unique for the period of XVIII It is dynasty.

The other radical transformation that Akhenaton undertakes by founding his new capital was to transfer the royal necropolis by abandoning the western shore of Thebes and the Valley of Kings. This unprecedented event also applied to the Great of the Kingdom, who renounced their Theban projects to be buried as close as possible to their sovereign. This change could not be done without the establishment in Akhetaton of a community of craftsmen, perhaps the very people who lived in Deir el-Médineh.

The noble necropolis [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

The burials of the notables were dug in the cliff, north and south of the city. There are few of them, about forty, intended for large dignitaries who had chosen to follow the pharaoh in its capital. The best preserved, the most beautiful also because decorated in the purest Amarnian style, are the tomb of Mahou, the chief of the police, and that of Aÿ, the successor of Touânkhamon. These tombs include column rooms, undoubtedly designed and developed on the model of the large ceiling rooms of the residences that the dignitaries occupied during their lifetime. In this, they are very similar to those that the courtiers of Amenhotep III In Thebes West, notably the Ramosé vizier which was contemporary with the two kingdoms and whose tomb also carries on its walls the first elements of the stylistic change inspired or imposed by Akhenaton himself.

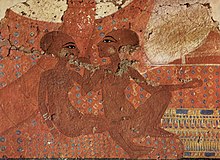

In Amarnian necropolises on the other hand, the sculpted scenes are exclusively made in the new Amarnian style and they all relate to life in Akhetaton. We see Pharaoh and his family to offer the god Aton, as well as descriptions of the striking palace of realism, although it is sometimes difficult to interpret them because of the non-personal way that the Egyptians had to represent the Buildings. The fact remains that these scenes contrast with the reliefs of the classic tombs. Thus, at the entrance, the owner is represented and his companion kneeling in front of the exit and making the gesture of prayer in front of a long text which is a hymn in the sun. In this way, they could benefit from the first rays of the rising sun and send him a prayer that the king himself would have written: the anthem to Aton.

The royal necropolis [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

A vast hypogeum located away in a desert gorge, the royal wadi, could be the tomb that sheltered the mummified body of Akhenaton, as well as those of the royal family, but nothing proves it. This hypogeum was designed to house the king’s body. A multitude of fragments of a red quartzite sarcophagus have been noted there, which has been reconstituted and is currently exhibited in the gardens of the Cairo Museum. This sarcophagus is very similar to those of the following reigns sculpted for Tounkhamon, Aÿ or even Horemheb and which we found in their tombs of the Valley of Kings. The major difference obviously lies in the cartridges with the names of the king and the god Aton, and especially in the fact that the four female characters who extend their protective wings around the sarcophagus are not the classic prophylactic goddesses that we will find later, but Well four representations of Nefertiti personified in Sothis, the star which in Egyptian mythology assured the eternal return of the annual flood during its heliac lifting. This last detail demonstrates that religious reform had reached all areas, including that of the resurrection, the prerogative of the god Osiris. Akhenaton also kept the main symbols and rites including that of mummification, what the remains of a canopes box or the or the Ouchebtis found in the royal hypogeum, but again as for the person of the King , the solarization had done his work, and Pharaoh was completely assimilated to the Sun God even in his tomb.

Another proof of this architecture. It was designed on a straight plane facing the east in order to receive the solar rays which theoretically could have penetrated in the depths of the vault. The very location of the necropolis completes the demonstration. He was not chosen in the west no longer, in the traditional domain of Osiris, but east of the city, in a wadi which, from the city, appears between two hills in the middle of which the sun rises each morning, The divine star that Pharaoh has his death will join for eternity. Thus Akhenaton returned to life every morning, to each new dawn. The religious revolution had therefore taken place even in the interpretation of the myth of the resurrection and this last act of faith, among others, was undoubtedly at the origin of the hatred that the pharaoh attracted to him after his disappearance, when his Successors will be unable to resist the pressures of the clergy of the great ancestral gods of the country, including that of Osiris in Abydos.

Another peculiarity of this hypogeum: just before the sarcophagus room are two side galleries, one of which leads to two other rooms, also unfinished, but whose decor is unusual in a royal tomb. The walls are indeed decorated with mourning scenes where we see Pharaoh and his queen crying Mâkhetaton one of their daughters who are dead around the twelfth It is year of the reign. It is a unique testimony of its kind, delivering one of the most touching aspects of the reign of Akhenaton. After the year XII , successive deaths to go to the royal family and began the extinction of the royal line. Mâkhetaton probably died in layers, because we can distinguish in the lower register a servant leaving the room where the deceased rests and taking an infant in her arms, while all the assistance seems grieved, which gives the scene a dramatic intensity.

Akhenaton probably wanted his daughters to be buried with him and thus transformed his hypogeum into a family vault. The other gallery would have been planned for Queen Nefertiti, but this hypothesis remains to be confirmed.

Near the royal tomb of other hypogeums had started to be arranged, but they were never completed. They were probably intended for other members of the Royal Court.

The Village des Artisans [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

Close to the southern necropolis, archaeologists have cleared a village of the craftsmen of Tell El-Amarna where the craftsmen lived with their families: around sixty houses built in clay bricks, comprising four rooms, and undoubtedly not very comfortable. Like Deir el-Médineh, the village was surrounded by a surrounding wall pierced with a single door, less to kidnap the craftsmen than to prevent the misappropriation of materials. However, unlike the royal city, and even the Theban example, the village of the craftsmen of Akhetaton was designed on a well -defined urban plan, with streets cutting at right angles and homes with standardized proportions. In this this village recalls the example of a Pyramid city From the Middle Empire discovered in Kahun at the entrance to the Oasis du Fayoum, near El-Lahoun, where Séstris II had built his funeral complex.

Amarnian art is unique, by its “expressionist” period (by comparison – abusive, but for lack of better – with certain works by German expressionist artists), then its naturalism, both based on the same spiritual motivations. These artistic forms and artistic practices seem to be radical with Egyptian art which had preceded, in the Middle Empire – although Séstris III Already a problem -then with strong personalities like Queen Hatchepsout and the King Thoutmôsis III . However, this “Amarnian revolution” which begins in Thebes, was very clearly announced under Amenhotep III and Queen Tiyi.

The scenes represented deviate completely from the traditional subjects of the Egyptian religion centered around the worship of Amon, images of the Egyptian monarchy by representing, for example, the royal family with its children. However, such images, the royal family, have long been the subject of anachronistic interpretations. A better knowledge of this period, over the past twenty years, has made it possible to dismiss many errors. Several major exhibitions, but also archaeological excavations have been able to considerably advance the state of this knowledge.

Typical objects of the Amarnian era were discovered in distant regions of Egypt as in the Palestinian region [ 7 ]

After the end of the Amarnian experience, Egyptian art returned to iconography and, gradually, to the traditional style.

- According to archaeologist Laboury 2010, p. 13 (taking up an argument from Sydney Hervé Aufrère), all these names are neologisms of archaeologists and “result from the mixture or confusion of the names of modern villages located on the site and the populations who live there. Since it is not a stratified mound called a Tell in near-East archeology and the Arab article ” he- »Has difficult to justify in front of these modern names created by Westerners, according to the most frequent use in archeology The Amarna designation is privileged. »»

- Laboury 2010, p. 16

- Laboury 2010, p. 21

- Laboury 2010, p. 22

- Kemp 2004, p. 281

- Egyptian art , French general bookstore, 1993, p. 344

- B. Mazar, « The Ancient City Jerusalem in the biblical Period », p. 1-8 dans Jerusalem revealed, Archology in the Holy City 1968-1974 , Y. Yadin ed., Yale University Press, New Haven, and The Israel Exploration Society, 1976.

Bibliography [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

- (in) Dorothea Arnold, The Royal women of Amarna : images of beauty from Ancient Egypt , New York (N.Y.), the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Abrams, , 169 p. , 29 cm. (ISBN 0-87099-818-8 , 0-87099-816-1 And 0-8109-6504-6 , read online ) , p. 63-67

- (in) Rita E. Freed, Yvonne J. Markowitz and Sue H. d’Auria (Scientific publishers) (Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 1999-2000), Pharaohs of the sun : Akhenaten, Nefertiti, Tutankhamen , London : Thames and Hudson ; Boston (Mass.) : Little, Brown and Company, 1999, , 316 p. , 29 cm (ISBN 0-500-05099-6 , read online )

- (in) Barry J. Kemp , Ancient Egypt. Anatomy of a Civilization , Routledge,

- Dimitri Laboury , Akhénaton , Paris, Pygmalion, , 478 p. (ISBN 978-2-7564-0043-3 )

- (in) Friederike Seyfried (exposure 2012), In the Light of Amarna: 100 Years of the Nefertiti Discovery: For the Egyptian Museum and Papyrus Collection State Museums in Berlin , Berlin, Berlin: Egyptian museum and papyrus collection, , 495 p. , 28 cm (ISBN 978-3-86568-848-4 And 3-86568-848-9 )

Related article [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

external links [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

Recent Comments