Blackbirding – Wikipedia

Per blackbirding We mean the capture of the indigenous people of some islands of the Pacific Ocean through deception and kidnapping to make them work in conditions close to slavery. Starting from the 1860s, the ships for fishing for cod of the Pacific Ocean began to look for workers to extract Guano’s deposits on the Chincha islands in Peru. [2] In the following decade, the trade of men focused on the supply of workers to the plantations, in particular to those of Queensland sugar cane and the Figi. [3] [4] The first documented practice of a great trafficking of sugar cane workers took place between 1842 and 1904. These people were recruited among the indigenous populations of the Pacific Islands close to northern Queensland. Even in the early years of the pearl collection in western Australia to Nickol Bay and Broome workers from the islands were used.

Blackbirding has continued almost today in developing countries. An example is the kidnapping and coercion under the threat of the indigenous populations of Central America to work as laborers in the plantations of the region, where they were exposed to heavy loads of pesticides and subjected to massacring works for very few money. [5]

The term could derive directly from a contraction of the expression “Blackbird Catching” (capture of the merlo).

For less than a year between 1862 and 1863 several Peruvian ships and some Chilene ships with Peruvian flag, they beat the smallest islands of Polynesia, the Easter island in the Eastern Pacific, the Ellice Islands (today Tuvalu) and the southern atolls of the Gilbert Islands (today Kiribati), looking for workers to overcome the problem of the extreme deficiency of labor in Peru. [2]

In 1862 J. C. Byrne, an Irish speculator, persuaded the farmers to financially support a plan to bring “colonists” from the new hebrides to Peru as contract agricultural workers. The first ship, the Forward , was equipped and on June 15, 1862 Sallò. Arriving in Tugareva, in the Pen Rew atoll, in the northern Cook Islands, Byrne found the only Pacific Ocean island where the population was arranged to leave due to a serious coconut famine. He hired 253 people who, by September, were at work in Peru as laborers in the plantations and as domestic.

Almost immediately speculators and shipowners of ships prepared the transport ships to allow them to go to Polynesia to enlist “settlers”. No less than thirty ships started from September 1862 in April 1863. Since profit was the main reason, many captains of recursed in dishonest tactics and kidnapping to fill the vessels.

Arrived [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

In June 1863, about 350 people lived in the Ata ‘Ata in Tonga, in a village called Kolomaile, whose remains were still visible a century later. The captain of the Tasmanian fishing boat Grecian , Thomas James McGrath, after decided that the new slave trade was more profitable than whale hunting, arrived in the Atoll and invited the islanders on board for a meeting. Once almost half of the population was on board, the doors of the ship were locked and the ship sailed. 144 people never returned to their island. The Grecian He also tried to catch slaves in the lau, but without success. In Niuafo’ou McGrath he only captured thirty people. This was Tonga’s second island to be hit. ‘Uiha should have been the third island approached, but there the islanders overturned the roles and held an ambush to the ship Margarita .

The Grecian He never arrived in Peru. Probably close to Pukapuka, in the Cook Islands, they met another ship, the General Prim , who had left Callao in March. His captain was willing to take delivery of the 174 tons to return quickly to the port, where he arrived on July 19th. In the meantime, the Peruvian government, under the pressure of foreign powers and also shocked by the fact that his work plan had turned into a slave trade, on April 28, 1863 he canceled all the licenses. The islanders aboard the General Prim And other ships could not therefore land. The islanders were then transferred to other ships rented by the Peruvian government to make them return to their homeland.

On October 2, 1863 the Forward , on which most of the Tongans were embarked, he left definitively, but many people had already died or in the end of life due to contagious diseases. Excurre, the captain of the Forward , he paid his own pocket his $ 30 per head tax, but landed on the uninhabited coconut island. Later he said that the 426 Kanakas were suffering from smallpox and were therefore a danger to his crew. When the whale Active He visited the island on October 21, his crew found about two hundred Tongani. A month after the Peruvian war ship Tumbes He went to save the remaining survivors and led them to Paita, where they apparently were absorbed by the local population.

In the meantime, in Tonga, King George Tupou I, having heard of these events, sent three Schooners to Ata to evacuate and reset the two hundred people who remained in Eua, where they would have been safe as future attacks. Nowadays their descendants still live in Ha’Atu’a.

Ellice Islands [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

Reverend A. W. Murray, the first European missionary in Tuvalu, [6] He described the practice of blackbirding in the ellice islands. He said that traffickers promised the islanders who would convert them while they worked in the production of coconut oil, even if the destination of the slaves were the chincha islands in Peru. Father Murray reported that in 1863 about 180 people [7] They were captured in Funafuti and two more hundred in Nukulaelae, [8] leaving in the latter island less than 100 of the 300 inhabitants recorded in 1861. [9] [ten]

Other islands [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

Bully Hayes, an American captain who reached fame for his activities in the Pacific Ocean in the years between 1850 and 1870, arrived in Papeete, Tahiti, in December 1868 on his ship Us With 150 men from Niue. Hayes offered them for sale as contractors or slaves for debts. [11]

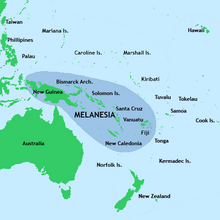

The expansion of the plantations in the Figi and Samoa, as well as the sugar plantations in Australia created other market destinations for men’s traffickers. The ships also beat the islands of Melanche and Micronesia, kidnaping workers to be employed in other places. In 1871 the first Anglican bishop of Melania, John Patteson, was killed on the island of Nukapu (one of the Solomon islands) by the indigenous populations five days after the traffickers killed a man and kidnapped five more.

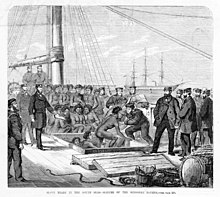

Many ships entered the slave trade with nefarious consequences on the islanders. The Royal Navy sent vessels from its base in Australia to try to suppress trade. In 1808, in fact, the United Kingdom and the United States of America had forbidden the trade of African slaves. However the ships of the Australian squadron ( HMS Basilisk , HMS Beagle , HMS Conflict , HMS Renard , HMS Sandfly It is HMS Rosario ) were unable to suppress blackbirding.

Since 1860, the great demand for labor in Queensland, Australia, sparked blackbirding in that region. Queensland was an independent British colony in north-eastern Australia until 1901, when it became a state of the Commonwealth of Australia. During a period of forty years, from the second half of the 19th century to the beginning of the twentieth century, the traffickers “recruited” Kanaka workers for Queensland sugar cane plantations, the new hebrids (today Vanuatu), the Papua New Guinea, of the Solomon Islands and the islands of the loyalty of New Caledonia as well as in Nue. The Government of Queensland tried to regulate trade: he asked all ships engaged in the recruitment of workers from the Pacific Ocean islands to bring a person in charge of the government to ensure that the workers were voluntarily recruited and not through deceptions. These government observers, however, were often corrupted by bonuses paid for workers recruited or blinded by alcohol and did little or nothing to prevent Marina’s captains from deceiving the islanders or kidnaping them with violent actions. [11] Joe Melvin, an investigative journalist, in 1892 became part of the crew of the Australian ship Helena And he did not report examples of intimidation or false declarations and concluded that the recruited islanders did it “willingly and absurdly”. [twelfth]

The generally coercive intake was similar to forced enlargement, once used by the Royal Navy in England. Between 55 000 and 62 500 Kanaka were brought to Australia. [13]

These people were called Kanaka (the French equivalent was canals And it is still used to refer to the Melanesians of New Caledonia) and came from the islands of the western Pacific: from the melania, from the Solomon islands and the new hebrids and a small number from the Polynesian and Micronesian islands such as Tonga (mainly ‘Ata), Samoa, Kiribati , Tuvalu and islands of loyalty. Many of the workers were actually slaves, but they were officially indicated with the term “contractors” or similar. Some Australian Aborigines, especially of the Capo York peninsula, were also kidnapped and transported to the south to work in farms.

The methods of blackbirding remained unchanged for a long time. Some workers were willing to be brought to Australia to work, while others were deceived or forced. In some cases, the ships of the traffickers (who made enormous profits) captured entire villages by attracting them on board with the excuse of trade or to attend a religious service and then starting quickly. Many died during the journey due to the unhealthy conditions and in the fields due to hard manual work. [14]

The number of people were actually kidnapped is unknown and remains controversial. The official documents and accounts of the period are often in conflict with the oral tradition handed down by the descendants of the workers. The stories of violent kidnappings still tend to stabilize in the first 10-15 years of trade.

Most of the 10 000 inhabitants of the Pacific Islands remained in Australia in 1901 were compulsorily repatriated between 1906 and 1908 pursuant to the Pacific Island Laborers Act of 1901. [15] Those who were married to an Australian were exempt from forced repatriation. Today, the descendants of these people are officially indicated as “South Sea Islanders”. A census from 1992 reported that about ten thousand South Sea Islanders lived in Queensland. Less than 3500 were reported in the 2001 Australian census. [13]

The era of Blackbirding began in the Figi Islands in 1865, when the first workers of the new hebrides and the Solomon islands were transported there to work on cotton plantations. The American Secession War had cut the supply of cotton to the international market when the union ships blocked southern ports. The cultivation of cotton was potentially an extremely profitable activity. Thousands of European plans arrived in the Figi to open new plantations but found the natives not willing to adapt to their plans. They therefore sought workers in the islands of Melania. On July 5, 1865 Ben Pease obtained the first license to introduce forty workers of the new hebrides in the Figi. [16]

British governments and Queensland tried to regulate this recruitment and the transport of workers. The Melanesian laborers had to be recruited for a period of three years at most, paid three pounds a year, and should have received basic clothing and the possibility of accessing emporiums. However, most of the Melanesians were recruited with deception, usually they were invited on board the ships with some excuses and then blocked. The conditions of life and work for them in the Figi were worse than those suffered by the subsequent Indian contract laborers. In 1875, the Figi medical officer, Sir William MacGregor, established a mortality rate of 540 out of 1000 workers. At the expiry of the three -year contract, the government imposed the commanders to transport workers to their villages, but most of the captains left them on the first island that saw in the waters of the Figi. The British sent war ships to enforce the law (in particular the Pacific Islanders Protection Act of 1872) but only a small part of the culprits was tried.

A well -known accident linked to Blackbirding was the 1871 journey of the Brigantino Carl , organized by Dr. James Patrick Murray [17] To recruit laborers for the Figi plantations. Murray ordered his men to wear white collar and bring black books, so as to seem missionaries. When the islanders embarked believing they had to attend a religious service, Murray and his men extracted the guns and forced the islanders to embark. During the journey Murray killed about sixty islanders. He was never tried for his actions, given that he was granted immunity in exchange for testimonies against the members of his crew. [11] [17] The captain of the Carl , Joseph Armstrong, was later sentenced to death. [17] [18]

Starting from 1879, British platforms organized the transport of Indian workers to the Figi islands. The number of Melanesian workers therefore decreased but continued to be recruited and employed in places such as sugars and ports until the beginning of the First World War. In addition, as told by the writer Jack London, the British ships and Queensland often used black crews, sometimes recruited among the islanders. Most of the Melanesian laborers were male. After the end of the recruitment, those who chose to remain in the Figi prayed for the wife of local women and settled in the areas around Suva. Their multicultural descendants identify themselves as a distinct community but, for strangers, their language and culture are indistinguishable from those of native figians.

The descendants of the forced originals of the Solomon Islands presented land demands to assert their right to traditional settlements in the Figi. A group that lived in Tamavua-I-Wai, in the Figi, received a verdict of the high court in their favor on February 1, 2007. The court rejected the complaint of the Christian Adventist Christian Church of the seventh day who asked the islanders to free a land on which they had lived for seventy years. [19]

The islanders fought and sometimes they were able to resist the practice of blackbirding. The historical events of Melamaia are now evaluated in the context of blackbirding with the addition of new materials from indigenous oral stories and in the interpretation of their culture. [20] A sensational event that attracted great attention in the United Kingdom was the assassination of the Anglican missionary John Coleridge Patteson, bishop of Melania, which took place in September 1871 in Nukapu, in the current province of Temotu, Solomon Islands. His death from the beginning was interpreted as resistance by local peoples to blackbirding. Patteson is considered a martyr from the Anglican Church. A few days before his death, one of the local men had been killed and five others had been kidnapped. [20]

However, an article in 2010 says that women played a greater and different role than they believed. When Patteson tried to convince his islanders to leave him his children to educate them in a distant Christian missionary school, Niuvai, wife of the supreme head and other women did not want to lose their children. She therefore persuaded men to kill the bishop. [20] An alternative theory is that Patteson destroyed the local hierarchy and in particular has threatened the patriarchal order. [20]

At the time, Pattenson’s death aroused clamor in England and contributed to the opening of the discussion on the practice of blackbirding. The United Kingdom later decided to annex the Figi to suppress this form of trafficking and slavery.

The American writer Jack London in his 1907 book The snark cruise , talks about an accident that occurred at the Langa Langa Langa in Malaita, in the Solomon Islands, when the local islanders attacked a “recruitment” ship:

|

“… he still wore the signs of the Tomahawk where the Melanesians of Langa Langa several months earlier had sneaked with the rifle and the ammunition closed in it, after having bloody the predecessor of Jansen, captain Mackenzie. The ship’s fire was somehow prevented by the black crew but this was so unheard of that the owner feared some complicities between them and the striker. However, this could not be tried and we sailed with most of this same crew. The current skipper warned us smiling that the same tribe still requested two other mini heads, to remedy the death in the YSABEL plantation. (page 387) [21] » |

In another step of the same book he wrote:

|

«We spent three unsuccessful days in Su’u. The Minota did not take any recruit from the Boscaglia and the premises did not take the head of the Minota (p. 270) ” |

- ^ Emma Christopher, Cassandra Pybus and Marcus Buford Rediker (2007). Many Middle Passages: Forced Migration and the Making of the Modern World , University of California Press, pp 188–190. ISBN 0-520-25206-3.

- ^ a b H.E. Maude, Slavers in Paradise , Institute of Pacific Studies (1981)

- ^ Emma Willoughby, Our Federation Journey 1901–2001 ( PDF ), are museum.vic.gov.au , Museum Victoria. URL consulted on June 14, 2006 (archived by URL Original on June 25, 2006) .

- ^ Reid Mortensen, (2009), “Slaving In Australian Courts: Blackbirding Cases, 1869–1871” , Journal of South Pacific Law , 13:1, accessed 7 October 2010

- ^ J Timmons Roberts and Nikki Demetria Thanos, Trouble in Paradise: Globalization and Environmental Crises in Latin America , Routledge, London and New York, 2003, p. vii.

- ^ Murray A.W., 1876. Forty Years’ Mission Work . London: Nisbet

- ^ the figure of 171 taken from Funafuti is given by Laumua Kofe, Palagi and Pastors, Tuvalu: A History , Ch. 15, Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific and Government of Tuvalu, 1983

- ^ The figure of 250 taken from Nukulaelae is given by Laumua Kofe, Palagi and Pastors, Tuvalu: A History , Ch. 15, U.S.P./Tuvalu (1983)

- ^ W.F. Newton, The Early Population of the Ellice Islands , 76 (2) (1967) The Journal of the Polynesian Society, 197–204.

- ^ the figure of 250 taken from Nukulaelae is stated by Richard Bedford, Barrie Macdonald & Doug Monro, Population Estimates for Kiribati and Tuvalu (1980) 89(1) Journal of the Polynesian Society 199

- ^ a b c James A. Michener & A. Grove Day, “Bully Hayes, South Sea Buccaneer”, in Rascals in Paradise , London: Secker & Warburg 1957

- ^ Peter Corris, ‘Melvin, Joseph Dalgarno (1852–1909)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/melvin-joseph-dalgarno-7556/text13185 , published first in hardcopy 1986, accessed online 9 January 2015.

- ^ a b Tracey Flanagan, Meredith Wilkie, and Susanna Iuliano. “Australian South Sea Islanders: A Century of Race Discrimination under Australian Law” Filed On March 14, 2011 on the Internet Archive., Australian Human Rights Commission.

- ^ Queensland Government, Australian South Sea Islander Training Package . are premiers.qld.gov.au . URL consulted on February 3, 2016 (archived by URL Original October 12, 2006) .

- ^ Documenting Democracy . are foundingdocs.gov.au . URL consulted on April 9, 2011 (archived by URL Original October 26, 2009) .

- ^ Jane Resture, The Story of Blackbirding in the South Seas – Part 2 . are janesoceania.com . URL consulted on 9 December 2013 .

- ^ a b c R. G. Elmslie, ‘The Colonial Career of James Patrick Murray’, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Surgery , (1979) 49 (1): 154-62

- ^ Sydney Morning Herald , 20-23 Nov 1872, 1 March 1873

- ^ Solomon Islands descendants win land case . are fijitimes.com , February 2, 2007. URL consulted on April 9, 2011 (archived by URL Original February 13, 2012) .

- ^ a b c d Thorgeir Kolshus e Even Hovdhaugen, Reassessing the death of Bishop John Coleridge Patteson , in The Journal of Pacific History , vol. 45, 2010, pp. 331–355, two: 10.1080/00223344.2010.530813 .

- ^ The Log of the Stark ( TXT ), are Archive.org . URL consulted on April 9, 2011 .

- Affeldt, Stefanie. (2014). Consuming Whiteness. Australian Racism and the ‘White Sugar’ Campaign . Berlin [et al.]: Lit. ISBN 978-3-643-90569-7.

- Corris, Peter. (1973). Passage, Port and Plantation: A History of the Solomon Islands Labour Migration, 1870–1914. Melbourne, Australia: Melbourne University Press. ISBN 978-0-522-84050-6.

- Docker, E. W. (1981). The Blackbirders: A Brutal Story of the Kanaka Slave-Trade . London: Angus & Robertson. ISBN 0-207-14069-3

- Gravelle, Kim. (1979). A History of Fiji . Suva: Fiji Times Limited.

- Horne, Gerald. (2007). The White Pacific: US Imperialism and Black Slavery in the South Seas after the Civil War . Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3147-9

- Maude, H. E. (1981). Slavers in Paradise . Fiji: Institute of Pacific Studies.

Recent Comments