Colfax massacre – Wikipedia

The Colfax massacre (Until the 1950s called by the historic tumult O Rivolta di Colfax) occurred on Easter Sunday 13 April 1873 in the territory of the parish of Grant, when about 150 African American were killed by white southerners; It was the most bloody racial carnage during the reconstruction era.

After the contested elections of 1872 for the governor of Louisiana and for other local offices, a large group of whites armed with rifles and a small overlooking cannon the freedmen and state militia occupying the headquarters of the district justice building [first] [2] . Most of the victims were killed after he surrendered; another 50 were murdered later that night after being held prisoners for several hours. The estimates on the actual number of the dead vary, passing from a minimum of 62 to a maximum of 153; Three attackers remained on the ground. The figures were difficult to determine above all because the bodies were largely thrown into the river or removed for a hasty burial. Voices were also scattered on the existence of mutual pits.

The historian Eric Foner described the massacre as the worst example of racist violence after 1865 [first] . It constitutes the bloodiest event in the federated state of Louisiana among the numerous acts of violence after the heated election campaign for the election of the governor. Foner writes that ” … Each election [in Louisiana] between 1868 and 1876 was characterized by rampant violence and pervasive fraud ” [3] .

At first the electoral committee, in which the anti -government “fusionists” predominated, declared the democrat John Mcenerry winner but then split, with the opposing faction that proclaimed the republican William Pitt Kelllogg winning. A federal magistrate of New Orleans then established that a state parliament was settled with a republican majority [4] .

The federal process and the condemnation of some material executors of the massacre pursuant to Enforcement Acts He reached the Supreme Court. In a key sentence, the one on the United States case against CruikShank (1876) [5] The Court established that the protections guaranteed by the XIV amendment did not apply to the actions of individuals, but only to those of state governments. Following this, the Federal Government found himself unable to prosecute the actions of the Paramilite Organization of the White League, which since 1874 had opened sections in the entire state territory. Intimidation, murders and repression of the vote of blacks by these paramilitary groups were helpful to the Democratic Party to regain the political control of the state parliament by force in the late 1870s.

Between the end of the 20th and the beginning of the 21st century, historians paid a renewed attention to the tragic events of Colfax and the case that led to the sentence of the Supreme Court, and their meaning in the context of the history of the United States of those decades .

In March 1865 the owner of James Madison Wells plantations, unionist, became the governor of Louisiana. While the state parliament, by democratic majority, approved the black codes that limited the rights of the freedmen, Wells began to offer to allow blacks to vote and at the same time suspend the right to vote to the former rebel secessionists. To achieve all this, a new state constitutional assembly convened for July 30, 1866 [6] . However, it had to be postponed due to the New Orleans massacre that occurred that day, in which Bianchi armed attacked blacks who were participating in a parade in support of the constitutional assembly itself. Providing for possible accidents, the mayor of New Orleans John T. Monroe requested the local military commander to supervise the city and protect the assembly [7] . The forces of Union Army did not however respond with sufficient promptness to avoid the massacre. A large number of blacks was attacked by white armed with clubs and weapons; The outcome was 38 dead, 34 black and four whites and more than 40 injured, mostly black [8] .

President Andrew Johnson blamed the massacre of the political agitation created by the Republicans, causing a national popular reaction against Andrew Johnson’s policies which led, in the mid -mandate elections of 1866, to a strong republican majority at the congress [9] . This approved the civil rights law of 1866 by climbing over Johnson’s veto. Previously the Freedmen’s Bureau and the occupying armies had prevented southerners that the “” black codes “, which had limited the rights of the freedmen and other blacks (including their work choices and places of life) entered into force [ten] . On July 16, 1866 the congress extended the duration and skills of the “Freedmen’s Bureau”, also in this case by canceling a veto of Johnson. On March 2, 1867 the first of the Reconstruction Acts which guaranteed the electoral rights of the blacks and which imposed the southern United States to approve the XIV amendment for their readmission in the Union [11] .

In April 1868 a coalition of whites and blacks in Louisiana had elected a state parliament by republican majority, but violence increased before the autumn elections; Almost all the victims were African American and some of the whites killed were republican activists. The insurgents also physically attacked people or burned their houses to discourage them from voting. President Johnson prevented the republican governor from using state militias or United States Armed Forces to cut off rebel groups, such as the so -called “Knights of the White Camelia” [twelfth] .

The elections in the parish of Winn and in the parish of Rapides were also marked by widespread violence. The area saw the cohabitation between large plantations and subsistence farmers; Before the war, the African Americans had worked there as slaves. William Smith Calhoun, an important owner of plantations, owned land for 14,000 acres (57 km 2 ) throughout the area. Former Schiavista, he lived with a mulatto woman in More Uxorio. He had come to support the political equality of the blacks [twelfth] .

On the day of the presidential elections of 1868 in November he led a group of freedmen to vote. The urn was originally located in a shop owned by John Hooe, who threatened to whip all the blacks who had tried to vote. Calhoun managed to make sure that the polls were transferred to the property of a republican. The Republicans obtained 318 votes and the Democrats 49. A group of whites launched the ballot box in the river and had Calhoun arrested for alleged electoral fraud. With the loss of the urn containing the electoral cards, the democrat Michael Ryan claimed an overwhelming victory [twelfth] .

After the electoral commissioner Hal Frazier, a black republican, was killed by Bianchi, Calhoun prepared a bill to create a new civil parish, the parish of Grant, forming it with a territory taken to both existing, that of Winn and that of Rapides; The proposal was approved by the state parliament controlled by the Republicans. Being a great owner of plantations, Calhoun thought that he would have had a greater political influence in the new jurisdiction, which had a black majority. Others were created to this by the state parliament to increase its political support [twelfth] .

After the settlement of the presidency of Ulysses S. Grant in 1869, the promulgation of the XV amendment was quickly reached, ratified on February 3, 1870; It guaranteed that the blacks, many of which were freshly released slaves, would have had full citizenship and therefore also the right to vote.

The Ku Klux Klan (Kkk) and other rebellious groups continued with their violent attacks and killed dozens of blacks in the South Carolina, in Georgia, Mississippi and elsewhere with the intent to discourage them from voting in the mid -mandate elections of 1870. The 31 of May of that year the congress approved a Enforcement Act based both on the XIV amendment and on the next. The following followed him KU KLUX KLAN ACT ( Civil Rights Act ), issued on April 20, 1871.

President Ulysses S. Grant used these laws to suspend the Habeas Corpus and use the federal army to cut off Klan’s terrorist violence [twelfth] .

The governor of Louisiana Henry Clay Warmoth strenuously struggled to maintain political balance in his state.

Among the people he named was William Ward, a war veteran of Union Army, chosen as commander of the “Compagnia A, 6th Infantry Regiment, militia of the State of Louisiana”, a new terrestrial military unit to be founded in the parish of Grant to help repress the violence both there and in other civilian parishes of the Red River valley. [13] .

Ward, born slave in 1840 in Charleston (Carolina del Sud), had learned to read and write while he was a servant of a teacher in Richmond (Virginia). In 1864 he fled and went to Fort Monroe (Virginia), where he entered the Union army and served until the definitive surrender of the Secessionist General Robert Edward Lee. [14] .

Around 1870 he arrived in the parish of Grant, where he had a friend; quickly became active among the local blacks in the Republican Party. After his appointment Ward recruited other freedmen for his troops; Many of these had also been war veterans. [15]

In Louisiana, republican governor Henry Clay Warmoth abandoned the “liberal republicans” (a group that opposed the reconstruction policies of President Grant) in 1872. Warmoth previously had supported a constitutional amendment that allowed the former confederates, to whom he had been denied the right to vote, to regain it. A “fusionist” coalition of liberal and democratic republicans presented the former confederate and democratic battalion commander John Mcenerry as a candidate. In return, Democrats and liberal republicans would have sent Warmoth to Washington as a senator of the United States. The republican William Pitt Kelllogg, one of the senators of Louisiana, oppose Mcenerry. The votes of November 4, 1872 resulted in disputes on who he had won, since the electoral committee, by majority “merger” (liberal and democratic republicans) declared Mcenerry winner but the minority of the committee proclaimed Kellogg winner. Both governors held settlement ceremonies.

Kellogg’s supporters did not manage to make the state court pronounce in their favor, and therefore appealed to the federal judge Edward Durell in New Orleans to intervene and ordered that Kellogg and the republican majority parliament were settled and that Grant authorized the troops of the Federal army to protect the Kellogg government. This action was highly criticized throughout the nation by the Democrats and by both the wings of the Republican Party because considered a violation of the rights of the States to manage their local elections. Therefore, the Investigative Committees of both Chambers of the Federal Congress in Washington were critical of Kellogg’s choice. The majority of the Chamber declared the action of Durell illegal and the majority of the Senate defined the Kellogg government “not much better than a successful plot”. In 1874 a commission of investigation by the Chamber in Washington recommended that the judge Durell was accused for corruption and illegal interference in the state elections of the Louisiana of 1872, but the judge resigned to avoid the infringement procedure. [16] [17]

McEnerry’s faction tried to take control of the state -arsenal to Jackson Square, but Kellogg used the state militia to block dozens of exponents of the McEnerry faction and to check New Orleans, where the state government was located. McEnerry returned to try to take control with a private paramilitary group. In September 1873 his forces, over 8,000 men, entered the city and defeated the state and citizen militia, with 3500 units in New Orleans. The Democrats took control of the Palazzo of the State Government, the Arma and the Police Stations, where the state government was then located, in what was known as the battle of Jackson Square. McEner’s troops controlled those buildings for three days, retiring before the arrival of federal troops. [3] [18]

Warmoth appointed the Democrats as chancellers of the parish of Grant and they made sure that the electoral lists included as many whites as possible and the least number of free blacks. The fusionists also made fraud on the day of the elections. As a result, the fusionists claimed an overwhelming victory in the parish, even if the black voters were more numerous than the whites, 776 against 630.

Warmoth appointed the Democrats of the Alphonse Cazabat and Christopher Columbus Nash, respectively judge of the parish and sheriff. Like many southern whites, Nash was a confederated veteran (as an officer, he had been for a year and a half prisoner of war in Johnson’s Island in Ohio). Cazabat and Nash lent a oath to the Colfax court on January 2, 1873 and sent the documents to the Governor Mcenerry to New Orleans.

William Pitt Kelllogg, for his part, on 17 and 18 January appointed candidates of the Republican list to the same positions. At that point Nash and Cazabat controlled the small and primitive court. The Republican Robert C. Register insisted that he, not Alphonse Cazabat, was the judge of the parish and that the republican Daniel Wesley Shaw, not Nash, had to be the sheriff. On the night of March 25, the Republicans took possession of the empty court and lent an oath. They sent their oaths to the Kellogg administration to New Orleans. [19]

Fearing that the Democrats would try to take over with the strength of the local institutions, the blacks began to build trenches around the district court and gave themselves the change to guard; The republican employees remained inside spending the night. In this way they maintained possession of the city for three weeks [20] .

On March 28 Nash, Cazabat, Hadnot and other white “fusionists” asked their supporters to arm themselves and gather with the aim of regaining the building on April 1st. Men were recruited by the nearby parish of Winn and from the surrounding ones. The Republicans Shaw, Register and Flowers organized an African American troop with the intention of defending the palace of justice [twelfth] .

The black republicans Lewis Meekins and William Ward, captain of the state militia and war veteran of the United States Colord Troops, broke into the houses of the opposition exponents, the judge William R. Rutland, Bill Cruikhank and Jim Hadnot. Gunshots were exchanged for the first time on April 2nd and then again on April 5; But the shots were too imprecise to produce damage. The two parts negotiated the fire, interrupted when a white killed, shooting him, a black, Jesse McKinney, described as a “spectator” [twelfth] . Another clash took place on April 6, ending with the whites on the run chased by the black armed. With the disorders spread throughout the community, black women and children joined the alleged men within the court to seek protection.

W. Ward, commander of Compagnia A, 6th infantry regiment of the Louisiana state militia, based in the parish of Grant, had been elected deputy to the state parliament in the republican list [15] . He wrote to Kelllogg asking for the sending of immediate reinforcements and entrusted the letter to William Smith Calhoun to deliver it; He embarked on the steam “Labelle” that spoken along the Red River (Mississippi), but was blocked by Paul Hooe, Hadnot and Cruikhank, who ordered him to tell the blacks to abandon the tribunal palace.

However, the defenders refused to leave, even if threatened by the armed gangs under Nash’s orders. To recruit the greatest number of men he had spread the voices that blacks were preparing to kill all white men and take their women [21] . On April 8 the anti-report newspaper Daily Picayune of New Orleans accentuated the tensions describing the events through the following title:

|

«The revolt in the parish of Grant. Frightening atrocities committed by the Negroes. No respect shown towards the dead [22] . » |

These false racist news pushed other whites in the area to join the Nash armed gang; They were all veterans of the Secession War. They appropriates a cannon that could shoot four -pound iron bullets. As Dave Paul said, a member of Ku Klux Klan: “Guys, this is a struggle for white supremacy!” [23] While suffering from tuberculosis and rheumatism, Captain Ward took a steam boat in New Orleans on April 11 to seek reinforcement directly from Kellogg. It was therefore not on the site during subsequent events [24]

Cazabat had ordered Nash, already appointed to sheriff, to cut off what he called a revolt. He organized a paramilitary group armed with Bianchi, assisted by former veterans officers confederated by the parishes of Rapides, Winn and Catahoula. He made these forces move to the court at noon on April 13, Easter Sunday. Nash led more than 300 whites, most on horseback and armed with rifles; According to reports, he would have ordered the defenders to surrender and exit without resistance. When his request was rejected, he gave half an hour to women and children camped outside to leave, and then opened fire. The clash continued for several hours with a few victims; But when the paramilitaries placed the cannon on the back of the building, some of the defenders, panicked, flew. About 60 of the latter ran away in the nearby dense bush trying to wade the river. Nash sent to their chase a group on horseback, which chilled most of them instantly.

In the meantime, Nash’s troops forced a black prisoner to set fire to the roof of the court. At this point, two white flags were raised from the inside, one produced with one shirt and the other with the page of a book. The shots ended.

The Nash group approached by ordering to all those who surrendered to throw the weapons and go out with raised arms: what happened immediately afterwards continues to remain the subject of discussion. According to some whites, James Hadnot was hit and injured by someone who was still within the court. Following the African American facts, on the other hand, “men in the court were stacking their rifles when the whites approached and Hadnot was hit from behind by a supervised member of his own band” [25] Hadnot died later, after being boarded downstream by a passage boat [26] .

The group of Bianchi armed reacted to the Hadnot wounding killing blacks; The black dead were 40 times greater than whites: historians describe the event as a massacre. The former secessionist soldiers killed unarmed men who tried to hide in the Palazzo del Tribunale, chased and killed those who ran away. They threw corpses into the river. About 50 survived that afternoon and were taken prisoner; Later that same night they were briefly killed by their jailers, who had drunk. Only a group of the group, Levi Nelson, was saved: he was hit by Cruikhank but managed to crawl away unnoticed. Subsequently he was one of the main witnesses of the accusation against the defendants of the murderous attacks [27] .

Kellogg sent the colonels of the state militia Theodore Deklyne and William Wright to Colfax with the arrest mandates for about fifty white attackers and have new local officers settle, the result of compromise. The two envoys found themselves in front of the still steaming ruins of the court and many of the corpses with wounds on the back of the neck or in the back of the skull [twelfth] . They described a completely charred body, the skull and the face of another crushed to the point of making its recognition impossible, another had the throat tightened. The survivors said that the blacks had dug a trench around the palace of justice to protect it from the attempt by the white democrats to “steal the election” [twelfth] , who had been attacked by whites armed with rifles, pistols and a cannon, which when the blacks had refused to leave the court had been set on fire and its defenders knocked down in cold blood. The whites accused the blacks of violating the white flag and of having been the cause of the disorders, the Republicans replied that it was not true and accused the whites of having captured and tied the prisoners in pairs and of having shot them behind the head [twelfth] .

On April 14, some elements of the new government police force arrived from New Orleans. A few days later two companies of federal troops also arrived; They set out to hunt the managers, but many of them had already taken refuge in Texas or on the hills. The agents drawn up a military relationship in which they identified three white victims and 105 African American by name; They also reported that they had recovered from 15 to 20 bodies not identified by the river waters [28] . They pointed out the heinous nature of many killings, assuming that the situation had been out of control.

The exact number of the dead was never accurately established; two federal agents ( marshal ) who visited the place of the massacre on April 15 and who made the victims buried, reported by 62 deaths [29] . A military report drawn up by a Congress Commission in 1875 identified 81 African American killed [30] , also estimating between 15 and 20 corpses that had been thrown into the river, plus another 18 buried in secret: for a total total of “at least” 105 [thirty first] . A state commemorative panel installed in the 1950s noted the deaths: 3 white and 150 blacks [32] .

The historian Eric Foner, a specialist of both the war of American secession and the era of reconstruction, wrote on the event:

| “As a more bloody case of racial massacre that took place in the era of reconstruction, Colfax massacre has taught many lessons, including the limits to which some opponents of the reconstruction would have gone to regain their traditional power. Among the blacks of the Louisiana, the accident was long remembered how the proof that in every great confrontation were inevitably found in a fatal disadvantage situation [first] . The organization against them had proved too strong. Later the state professor and parliamentarian of the reconstruction John G. Lewis observed: “They attempted [The Army Autodifesa] in Colfax. The result was that on Easter Sunday of 1873, when the sun set, he did it on the corpses of two hundred eighty blacks ” [first] . » |

James Roswell Beckwith, the district prosecutor based in New Orleans, sent a telegram on the massacre to the prosecutor General George Henry Williams. National newspapers from Boston to Chicago took care of the Colfax massacre [33] . Several government agents sent on the spot spent weeks in an attempt to arrest the members of the paramilitary organization involved, leading to a total of 97 offending white men. In the end, Beckwith accused nine and brought them back to the violation of the Enforcement Act of 1870, designed to give federal protection to the civil rights of the freedmen, based on the 14th amendment , Against terrorist groups such as Ku Klux Klan. The accusations were murder and conspiracy against the rights of African Americans; Two criminal proceedings were held in succession during 1874.

William Burnham Woods presides over his first, showing himself solidarity with the accusation. If there had been convictions, the culprits would not have been able to challenge the sentence before any Court of Appeal, according to the rules of time [twelfth] . However, the prosecutor did not prove to be able to obtain a sentence; An accused was acquitted, while for the other eight there was an error of procedure.

In the second trial, three defendants were judged guilty of sixteen accusations [twelfth] . However, the president of the jury, Joseph Philo Bradley, associated judge of the Supreme Court, declared the sentences inflicted by saying that the accusations violated the principle of ownership of the criminal action by the state [twelfth] , who had not been able to demonstrate a racial motive for the massacre or who were vague. He therefore ordered that the men were released behind deposit, and these immediately made themselves unavailable [twelfth] [34] .

The public accusation appealed and the Supreme Court examined him as the United States against Cruikhank in 1875. The sentence established that the Enforcement Act It could only be applied to the actions committed by a state and not to those committed by private individuals or by private associations. The Federal Authority could therefore not pursue cases such as Colfax’s mass killings. The high court stated that those who believed they had suffered a crime had to request protection from the state: however, Louisiana did not pursue any of the authors of the massacre and the most of the southern United States would never have pursued the whites for racial violence and the murders of Neri.

The advertising of the facts thanks to the printed paper and the subsequent decision of the Supreme Court substantially encouraged the growth of racist white paramilitary organizations. In May 1874 Nash created the first section of the White League, directly transforming its armed gang, and others were soon formed in many areas of the state, as well as in the southern areas of the neighboring ones. Unlike the KKK, they made propaganda publicly and often in a widespread way. The authoritative historian of the George C. Rable period described them as “the military arm of the Democratic Party” [35] .

Other formations also arose, for example the Red Shirts, especially in the South Carolina and Mississippi, states that had a majority of the black population. They widely used violence and political murder in order to terrorize the heads of the freedmen and the white representatives of the Republican Party and to repress the right to vote among African American citizens for all the years 1870: the victims could do very little for try to defend yourself. In August 1874 the White League fell with violence the owners of republican charges from Coushatta (Louisiana), in the parish of Red River, killing the six whites before they could leave the state and from 5 to 15 freedmen who were witnessed. Four of the victims were connected to the deputy of the Chamber of Representatives of the area [36] .

The acts of widespread violence served to intimidate both the voters and the public officials in charge; It was one of the main methods that southern white democrats used to regain full control of the state legislative assembly during the presidential elections of 1876 and, finally, to dismantle the era of reconstruction throughout the Louisiana.

In 1920 a committee to Colfax was set up to finance a commemorative stele of the three whites killed; It is located in the Colfax cemetery and recites ” Erected to the memory of the heroes, / parish of Stephen Decatur / James West Hadnot / Sidney Harris / Who fell into the Colfax revolt fighting for white supremacy ” [37] [38] .

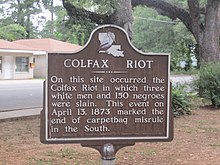

In 1950 the Louisiana placed a road commemorative panel that recalled the 1873 event as “Colfax revolt”, so traditionally called in the white community. The panel recited: “On this site the Colfax revolt took place, in which three white men and 150 niggers were killed: this event, on April 13, 1873, marked the end of the bad governance of the southern United States by carpetbagger” [37] [39] . The panel was removed on May 15, 2021, to be moved to a museum. [40]

Colfax massacre is among the events of the reconstruction and history of the United States who received a new national attention at the beginning of the 21st century.

In the two-year period 2007-08 two new books were published on the theme: The Colfax Massacre: The Untold Story of Black Power, White Terror and the Death of Reconstruction [41] [42] by Leeanna Keith [43] It is The Day Freedom Died: The Colfax Massacre, the Supreme Court and the Betrayal of Reconstruction [44] of the journalist Charles Lane. The latter in particular faced the political and legal implications of the case that came before the Supreme Court, which arose from the accusation of several men belonging to white paramilitary groups. A documentary film is also in preparation.

- ^ a b c d Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 , p. 437

- ^ Ulysses S. Grant , People and Events: “The Colfax Massacre”, PBS Website Filed On April 21, 2004 on the Internet Archive., Access Apr 6, 2008

- ^ a b Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863-1877 , New York: Perennial Library, 1989, p. 550

- ^ Lane, 2008, Pag. b13 .

- ^ Form

- ^ Michael Holt, By One Vote , Lawrence, Kansas, University Press of Kansas, 2008, p. 196.

- ^ Avery Craven, Reconstruction , Boston, Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1969, pp. 186 .

- ^ Avery Craven, Reconstruction , Boston, Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1969, pp. 187 .

- ^ Francis Simkins e Charles Roland, A History of the South , New York, Alfred A. Knopf, 1947, p. 262.

- ^ John Ezell, The South Since 1865 , New York, Macmilan, 1975, pp. 47 -48.

- ^ J. G. Randall e David Donald, The Civil War and Reconstruction , Boston, D. C. Heath, 1961, pp. 633 –34.

- ^ a b c d It is f g h i j k l m n Lane, 2008 .

- ^ Lane, 2008, pag. 54 .

- ^ Lane, 2008, pag. 55 .

- ^ a b Lane, 2008, pag. 56 .

- ^ William Hesseltine, “Grant the Politician”, 344

- ^ Charles Lane, *The Green Bag*, “Edward Henry Durell,” 167-68

- ^ Jeffry Wants, General James Longstreet , New York, Simon & Schuster, 1993, pp. 416 .

- ^ Lane, 2008 .

- ^ Keith’s Leems, The Colfax Massacre: The Untold Story of Black Power, White Terror, & The Death of Reconstruction , New York, Oxford University Press, 2008, p. 100, ISBN 978-0-19-5

- ^ Keith (2007), The Colfax Massacre , p. 117

- ^ Lane, 2008, pag. 84 .

- ^ Lane, 2008, pag. 91 .

- ^ Lane, 2008, pag. 57 .

- ^ Nicholas Lemann, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War , New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, paperback, 2007, p.18

- ^ Lemann (2007), Redemption, p. 18

- ^ Lane, 2008, pp. 123-124 .

- ^ “Military Report on Colfax Riot, 1875” , Congressional Record ], Access 6 April 2008

- ^ Lane, 2008, pag. 265 .

- ^ Find a grave memorial on the Colfax Massacre has 80 names listed

- ^ Lane, 2008, pp. 265-66 .

- ^ Louisiana Department of Culture, Recreation and Tourism, Colfax Riot Historical Marker . are stoppingPoints.com , 1950.

- ^ Lane, 2008, pag. 22 .

- ^ Nicholas Lemann, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War , New York; Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2006, p.25

- ^ George C. Rable, But There Was No Peace: The Role of Violence in the Politics of Reconstruction , Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1984, p. 132

- ^ Eric Foner (2002), Reconstruction , p. 551

- ^ a b Richard Rubin, The Colfax Riot , in The Atlantic Monthly , The Atlantic Monthly, luglio–August 2003. URL consulted on June 2009 .

- ^ ( IN ) Colfax Riot Memorial , in Find a Grave .

- ^ Keith (2007), Colfax Massacre, p. 169

- ^ Charles Lane, Opinion: Not far from Tulsa, a quieter but consequential correction of the historical record , in The Washington Post , 9 June 2021. URL consulted on June 9, 2021 .

- ^ Google Boos

- ^ Form

- ^ Form

- ^ Form

- Eric Foner, Reconstruction: America’s Unfinished Revolution, 1863–1877 , 1st, New York, Harper & Row, 1988.

- Robert M. Goldman, Reconstruction & Black Suffrage: Losing the Vote in Reese & Cruikshank , Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2001.

- Hogue, James K., Uncivil War: Five New Orleans Street Battle and the Rise and Fall of Radical Reconstruction , Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2006.

- Keith’s Leems, The Colfax Massacre: The Untold Story of Black Power, White Terror, & The Death of Reconstruction , New York: Oxford University Press, 2007

- KKK Hearings, 46th Congress, 2d Session, Senate Report 693 .

- Charles Lane, The Day Freedom Died: The Colfax Massacre, the Supreme Court, and the Betrayal of Reconstruction , New York, Henry Holt & Company, 2008, ISBN 978-1-4299-3678-1.

- Nicholas Lemann, Redemption: The Last Battle of the Civil War 1st ed. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2006.

- Richard Rubin, “The Colfax Riot” , The Atlantic , Christmas/Aug 2003

- Joe G. Taylor, Louisiana Reconstructed, 1863-1877 , Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1974, pp. 268–70.

Recent Comments