Comics — Wikipedia

Comics is the term used in the United States to designate comics. It comes from the word meaning “comic” in English because the first comics published in the United States were humorous. However in the French -speaking world, the meaning has been limited to specifically designate American comics.

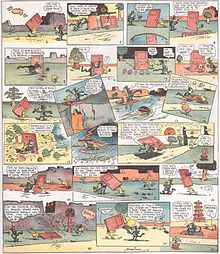

Appeared at the end of XIX It is century, the ‘ comic strips » Are short comics of a few boxes published in the press, generally extending on a band in the week ( ‘ daily strip » ), an entire page on weekends ( ‘ sunday strip » ) and most often telling a short humorous story, or sometimes an adventure, in the form of a soap opera.

THE comic books are periodicals of a few tens of pages telling a developed story, published in fascicles with regular periodicity, which appeared in the 1930s. If all genres are represented, the best known are those staged superhero, edited by DC Comics and Marvel Comics, which participate in comics mainstream . With the birth of comics underground In the 1960s, followed by alternative comics This format also allowed the comic strip of American author to express themselves in all its diversity.

Comics having struggled to be recognized as an art in its own right in the United States, the term ‘ graphic novel » ( “Graphic novel” ), which appeared in the 1970s, began to become particularly popular since the 1990s. Forged to designate more ambitious comic albums than the comic books genre and published by alternative publishers, it was quickly overused and today designates above all a format, the album, whether it is an original creation or the compilation of planks first published in of the comic books . Graphic novel is now sometimes disputed as pretentious. The collections of comic strips are usually called reprints or anthology . Other modes of publication, such as fanzines, small press Or webcomics are also from the United States.

In France [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

In France, the term comics appeared quite recently. In the 1980s, publishers began to employ the term comics , first for more mature works that were not in the superhero genre, then to qualify the superhero genre so that the term has almost become synonymous with “Superhero comic strip” , this genre being the predominant genre in the United States. Indeed, Disney comics or those of newspapers are rarely or never called comics although being American. With the arrival of Japanese comics, called manga, the trend of calling comics the American comic strip has been strengthened.

Origins [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

In 1842, a pirate edition of comics appeared in the United States The loves of M. Vieux-Bois by Rodolphe Töpffer [ P 1 ] which is followed by the publication of the other works of this author, always in the form of Pirate editions [ first ] . American artists then have the idea of producing similar works. Journey to the Gold Diggins by Jeremiah Saddlebags by James A. and Donald F. Read was in 1849 the first American comic strip [ S 1 ] , [ G 1 ] .

The boom in comics must wait, however, when the newspapers are starting to compete fierce and that to attract the reader of the press of the press William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer decide to publish comics in their newspapers [ 2 ] . Many important series then see the light of day and the grammar of comics is set up. In 1894, Joseph Pulitzer published in the New York World The first color strip, designed by Walt McDougall [ D 1 ] . The same year, in the New York World , Richard F. Outcault propose Hogan’s Alley and on October 25, 1896, the main character in this series, the Yellow Kid , pronounces his first words in a phylactère [ 3 ] .

The stories of a few boxes arranged horizontally on two bands or a page are quickly essential: this is the beginning of Comic strips [ n 1 ] . In 1897, Rudolph Dirks created in American Humorist , weekly supplement of New York Journal , The Catzenjammer Kids (PIM PAM POUM) . Very quickly, Dirks uses bubbles and his comic book series becomes the first to systematically use linear narration) [ A 1 ] . From September 24, 1905, Winsor McCay published Little Nemo in Slumberland in the New York Herald of pulitzer [ Has 1 ] .

In 1903 that the first daily strip (“Daily band”), that is to say the first comic strip Published daily, in black and white, in the interior pages of a newspaper but the band was not essential and it was not until 1907 to see a new test. November 15 of this year is published in the San Francisco Chronicle the hearest Mr A. Mutt Starts In to Play the Races [ n 2 ] of Bud Fisher. Shortly after, Fisher adds to Mutt an acolyte, Jeff, and the series becomes Mutt and Jeff [ D 2 ] , [ H 1 ] . The success of the series this time brings the other newspapers to offer daily strip a black and white band during the week and a sunday strip of a page or a half-color in color on Sunday [ H 2 ] . Five years later, Hearst is at the origin of another innovation that deeply structures the comic strips : Systematic syndication. The authors must assign their diffusion rights to the publisher. This can then offer American newspapers and around the world subscriptions to the various works in its catalog, allowing the author to experience a much greater dissemination than if he only published in a single daily [ F 1 ] .

Among the series of this time, some are intended to become classics like Kat , de George in the Herriman, Polly and Her Pals The Cliff Sterrett, Gasoline Alley The Frank King, Little Orphan Annie [ n 3 ] Created by Harold Gray, Popeye of E. Segar, etc.

There are also adaptations of existing characters such as Mickey Mouse or Tarzan, Drawn by Hal Foster from the character of Edgar Rice Burroughs.

Apparition [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

In 1933, American comics experienced a new revolution with the appearance of comic books , first free then from 1934 paid. In February of that year, it seems Famous Funnies , and comic book of a hundred pages sold at a price of ten hundred and which takes up newspaper strips [ K 1 ] . In 1938, a publishing house called National Allied Publications decided to launch a new comic book appointed Action Comics in which appears the first superman superhero, created by Joe Shuster and Jerry Siegel [ K 1 ] . The success is immediate and soon many publishers will offer comics of superheroes and DC will also continue on this path and offer in number 27 of Detective Comics , Batman, created by Bob Kane and Bill Finger [ B 1 ] .

The appearance of the comic book does not mean the end of the comic strip and many major series appear: The ghost ( The Phantom ) the Lee Falk [ 4 ] , Prince Vaillant [ n 4 ] The Hal Foster [ 5 ] , Spirit , de will Eisner, Pogo the Walt Kelly [ 5 ] . October 2, 1950 appeared the first strip of Peanuts by Charles Schulz [ 6 ] . The most popular strips are then disseminated in hundreds of newspapers and are read by tens of millions of people [ I 1 ] .

In 1940, when war threatened, appeared Captain America , created by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby. The title will launch the wave of patriotic superheroes which will be the norm when war broke out [ 7 ] . From the end of the war, these heroes having no more enemies disappear [ C 1 ] . However, superhero comics are not those that dominate the market. The most important genre is that of comics featuring anthropomorphic animals like Mickey Mouse or Bugs Bunny [ G 2 ] But other genres also have success: humorous comics [ G 3 ] , educational comics, series featuring adolescents and even information comics [ 8 ] . Nevertheless, it is superheroes and humanized animals that dominate the market [ G 4 ] .

After war [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

After the war, the patriotic superheroes disappear and the other superheroes also lose their readers, who prefer to turn to other genres such as police comics whose sales are progressing strongly, as Crime Does Not Pay which sells for more than a million copies [ P 2 ] . Another genre appears after the war, that of the romance comics which appeared in 1947 with the publication of Young Romance by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby. The success is immediate (sales between the first and third issue are tripled [ Are 1 ] ) and imitations flourish [ P 2 ] . Horror comics are the third genre that attracts readers. The publishing house EC Comics launched his first horror comics in 1949 Crypt of Terror And The Vault of Horror who will also be imitated [ P 3 ] . These three genres will however disappear. In 1950, the romance market was saturated and finally collapsed: the number of series was divided by two between the first and the second half of 1950 and in 1951, only thirty series were still published [ B 2 ] . In 1954, it was the establishment of a censorship organization, the comics code , instituted by publishers to avoid the establishment of state censorship, which brings the brutal stop of police and horror series [ 9 ] . In September 1956 began a new period called the age of comics, which above all refers to developments in Books comics. This month appears, at DC Comics, the n O 4 of comic book Showcase in which the character of Flash is recreated [ ten ] . Subsequently, still in this same comic book Other characters are created who win their own series, which definitively launches the age of money.

Seeing that the superhero gender is fashionable, the Marvel Comics publishing house launches series of the same kind, written by Stan Lee. The fantastic four therefore appear in August 1961 drawn Jack Kirby who also participated in the development of the plot [ 11 ] , Hulk in May 1962 (Lee and Kirby), Thor in August 1962 (Lee and Kirby), Spider-Man in August 1962 (Lee and Steve Ditko), Iron Man in March 1963 (Lee and Don Heck), X-Men And the avengers both in September 1963 (Lee and Kirby), etc. The success of these series made Marvel the first publishing house in front of DC [ C 2 ] . Next to the superhero comics, we continue to find westerns, war stories, espionage, etc. [ twelfth ] published by DC and Marvel but also by other publishers such as Gold Key , Dell Comics , Gilberton Publications , Harvey Comics or Charlton Comics .

While the editing of comics, subject to the code comics, is integrated into an organized creation and distribution circuit, a new form of comics intended for an adult audience is developing. THE comics underground , or “Comix”, are characterized by their freedom of your willingly provocative and carrying a critical discourse on American society. Diffusion circuits, underground newspapers [ 13 ] or Fanzines [ And 1 ] ), are original and thus escape censorship. They were born during the rise of protest movements of the 1960s and 1970s and most often developed a critical discourse of American society. The prints are confidential but their influence is important [ N 1 ] . Little by little, this type of comic strip develops: the number of comix published increases (300 in 1973) and sales sometimes amounts to the tens of thousands of copies. This good health lasts the time of claiming movements and when the dispute weakens comix sales are affected [ B 3 ] . The underground scene gradually turns into an alternative scene [ B 4 ] .

Since the 1970s [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

After the golden age and the age of money, the bronze age is a period of difficulties both for comic books and for comic strips but also an innovation period to try to fight against these difficulties. The Bronze Age, whose start date varies according to the authors, extends during the 1970s and 1980s. One of the first characteristics of this “Bronze Age” is the realism which is essential at the expense of A sometimes childish appearance [ C 3 ] . This evolution of the content of the comics is to be linked with the changes of American society: struggle for the recognition of ethnic minorities [ B 5 ] , questioning of the authority [ 14 ] . The world of comics is then more complex and darker [ B 6 ] .

Comics sales during this period decrease [ P 4 ] But some series resist, like Superman or Batman, who benefit from a base of loyal readers. New series are essential because they benefit from the presence of young talented authors. This is the case of the X-Men, recreated in 1975, when they were taken in hand by Chris Claremont and John Byrne [ P 5 ] . New personalities emerge when at the same time new genres appear on the stands such as heroic fantasy, horror or kung fu. As for the Underground comics, it also evolves by abandoning its demanding aspect and becoming the place of the personal expression of the authors. We are no longer talking about underground but alternative comics, which will find new distribution places that are stores specializing in the sale of comics [ 15 ] . In addition, the authors find new publishers ready to publish their works. This metamorphosis of the alternative underground finds an obvious example in the journey of Art Spiegelman, first an underground author then founder of a RAW review where he publishes Maus [ S 2 ] . Spiegelman published in 1986 the first volume of Maus (entitled Maus: A Survivor’s Tale ) which will be followed in 1992 of Maus: from Mauschwitz to the Catskills worth to the author a special pulitzer prize in 1992 [ 16 ] .

The mid -1980s was often marked as a period of changes designated as the modern age of comics. Indeed, in 1985 appeared Crisis on Infinite Earths by Marv Wolfman and George Perez which allows the recreation of the DC universe. Then in 1986 came out The Dark Knight Returns by Frank Miller and Watchmen from Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons. The themes are more adult and violence is more visible than in a classic comics. However, these major series in the history of comics cannot hide the continuous crisis that the comics industry is experiencing whose sales are constantly decreasing. The early 1990s seem to see a renewed interest in comics but this is actually a straw fire due to a speculative bubble which leads people to buy comics, sometimes in several copies, by making the bet that their value will fly away. When this fallacious hope faints, sales collapse. The consequences are a disappearance of publishing houses and comic stores as well as a concentration in the field of broadcasting [ P 6 ] . This crisis leads publishers to treat the content of their comics: cinema, television or novelists are called to write comics scenarios, the scenarios are more complex, the stories are more realistic and the psychology of the characters is better developed . In addition to attracting the reader who could fear getting lost in an existing universe sometimes for over 60 years, the recreations are common. The series take a new start to follow the story even if the hero’s past is not known by the reader [ P 7 ] . Randy Duncan and Matthew J. Smith speak of an “age of reiteration” to characterize this period in which heroes are constantly recreated, whether in the classic universe or in alternative versions [ P 7 ] .

Next to the two major comics publishers, Marvel and DC, who dominate the market [ 17 ] , publishers, qualified as independent, manage to exist by most often offering more personal works and in genres other than that of superheroes. In these cases, the comic book format is no longer necessarily chosen and the form of the graphic novel can be preferred [ 18 ] .

The adaptation of comics is a relatively old phenomenon which largely precedes that of other types of comics (“Franco-Belgian” and “manga”). THE Flash Gordon of Alex Raymond is thus adapted in serial (television series) From 1936 and this audiovisual product had an important success (since it gave rise to two suites). According to Nicolas Labarre, in an article published in Comicities , the adaptation is very faithful since it directly takes up certain boxes of the different books and almost assimilates the comic to a form of story board (such is also the case with the adaptation of Watchmen ). On the other hand, the adaptation of this comic seems to pose a problem in terms of cultural hierarchy and invites us to think about the relationship that we have with the different media mobilized by our cultural practices: “ Yet, in all these cases, the enthusiasm or disdain with which the serial is described strongly differs from the reverence devoted to Raymond’s work. While both cultural objects have survived to some extent, they now occupy very different places within popular culture » [ 19 ] .

There was 53 adaptations of comic-books made between 2000 and 2015 for the cinema, two of which had the main character a woman [ 20 ] .

Differences with Franco-Belgian comics [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

These differences are generalizations which mainly concern comics mainstream .

- THE comic books Go out in the form of a booklet reached on a regular basis (monthly), and ask for the involvement of different artists to go out on time: very often, there is a screenwriter, a designer, an ink, a letter, a colorist. The European album does not exist or prepublication in magazine. The term ” graphic novel »Cover everything that is not booklet, be it the big volumes in black and white ( A contract with God de Will Eisner is considered one of the first graphic novels historical), formats ” over-sized », Or« tabloid “, Modeled on Franco-Belgian albums, even” trade paperbacks Who compile pre -published stories in booklets.

- The characters and the series do not belong to the creators, but to the publishers. Unless the author self-public or if he manages with the publisher to hold the law of his series, which is not the norm. This is why most comics regularly change writers and designers during their existence.

- The series are under the direction of a editor -in -chief who has his say on the general orientation of the series. He can decide that a series is no longer viable as is and asking for the change in creative team. He can also ask for significant changes (death of a character, change of costume) to arouse the interest of readers again. Among the questionable editorial decisions we can cite the “reboot” (new start of the series at the number 1 to attract a new readership).

- The distribution system is different in the United States. The comics were once sold exclusively in kiosks and drugstores (Drugstores) and are now available almost only in ” comics-shop », Specialized stores. Publishers are trying to expand their distribution mode by publishing ” trade paperbacks (Collection bringing together several episodes of the same series, in order to form a complete history) on the bookstore shelves of large surfaces or in generalist bookstores such as the Barnes & Noble points of sale chain.

Notes [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

- Literally: “humorous bands”.

- M. A. Mutt embarks on the hippical bet.

- Annie, the little orphan

- Prince Valiant

References [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

Bibliographic references [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

- Charles Coletta, « Detective Comics », p. 150.

- Michelle Nolan, « Romance Comics », p. 523.

- Randy Duncan, « Underground and Adult Comics », p. 650

- Randy Duncan, « Underground and Adult Comics », p. 654.

- Tim Bryant, « Ages of Comics », p. 13.

- Chris Murray, « Cold War », p. 109.

- p. 25

- p. 37

- p. 38.

- p. sixty one

- p. 62.

- p. 76-77.

- p. 79.

Other references [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

- Florian Ruby « Comics From the Crypt to the Top : panorama des comics en français », DBD , n O 61, , p. 39 (ISSN 1951-4050 ) .

- Florian Ruby « Comics From the Crypt to the Top : panorama des comics en français », DBD , n O 61, , p. 45 (ISSN 1951-4050 ) .

- Denis Lord « Bandles: French -speaking phylactera celebrates its 100th anniversary », The duty , ( read online ) .

- Bernard Coulange, ‘ Bengal ghost » , on www.bdoubliees.com , Bernard Coulange (consulted the ) .

- Florian Ruby « Comics From the Crypt to the Top : panorama des comics en français », DBD , n O 61, , p. forty six (ISSN 1951-4050 ) .

- Stephen J. Lind, ‘ Reading Peanuts : the Secular and the Sacred » , ImageTexT: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies , on http://www.english.ufl.edu/imagetext/ , English Department at the University of Florida, (consulted the )

- Gianni Haver and Michaël Meyer, “From interventionism to commitment. Comic books during the Second World War »in Images at war, under the direction of Philippe Kaenel and François Vallotton, Lausanne, Antipodes, 2008.

- Gianni Haver, Michaël Meyer, “Stranger than fiction. Comic Information and Cinema Books “, in Boillat A. (DIR), Les boxes on the screen. Comics and cinema in dialogue. The Equinox, Georg, Geneva, 2010, pp. 197-219.

- (in) ‘ The Press : Horror on the Newsstands » , Time magazine , , p. first ( read online ) .

- (in) Roy Thomas , ‘ Who Created The Silver Age Flash? » , Another self , vol. 3, n O 10, ( read online ) .

- (in) ‘ Digital Comics: Fantastic Four (1961) #1 » , Marvel Comics (consulted the )

- (in) Craig Shutt , Baby Boomer Comics : The Wild, Wacky, Wonderful Comic Books of the 1960s , Krause Publications, , 207 p. (ISBN 978-1-4402-2741-7 , read online ) , p. 17 .

- Lambiek Comic Shop and Studio in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, ‘ Underground Comix Overview by Lambiek » , on lambiek.net , (consulted the ) .

- (in) Bryan E. Vizzini , « Comic Books » , in Roger Chapman, Culture Wars: An Encyclopedia of Issues, Viewpoints, and Voices , M.E. Sharpe, ( read online ) , p. 106 .

- (in) Stephen Weiner , One Hundred and One Best Graphic Novels , Nbm, , 2 It is ed. , 60 p. (ISBN 978-1-56163-443-9 , read online ) , p. XIV .

- ‘ The Pulitzer Prizes : Special Awards and Citations » , www.pulitzer.org (consulted the ) .

- (in) Shirrel Rhoades , Comic Books : How the Industry Works , Peter only, , 406 p. (ISBN 978-0-8204-8892-9 , read online ) , p. 2 .

- Jean-Paul Gabilliet, ‘ From comic book to graphic novel: the Europeanization of American comics » , on www.imageandnarrative.be , Image & Narrative, (consulted the ) .

- Nicolas Labarre, “Two flashes. Entertainment, Adaptation: Flash Gordon as Comic Strip and Serial “, Comicities [online], media, posted on May 19, 2011, consulted on January 05, 2014. URL: http://comicalites.revues.org/249 ; DOI : 10.4000/comicalites.249.

- ‘ Superheroines in Gotham City: an intermedial study of the redefinition of gender roles in the universe of Batman. » , on theses.fr , (consulted the ) .

Bibliography [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

![]() : document used as a source for writing this article.

: document used as a source for writing this article.

- (in) Frederick Luis Aldama (dir.), Multicultural Comics. From Zap to Blue Beetle, Austin : University of Texas Press, coll. « Cognitive Approaches to Literature and Culture », 2010, p. . (ISBN 9780292722811 )

- Annie Baron-Carvais , Comics , Paris, Puf, coll. “What do I know? “, , 127 p. (ISBN 2-13-056107-1 )

- (in) Mike Benton, The Comic Book in America. An Illustrated History , Dallas : Taylor Publishing Company, 1989.

- (in) M. Keith Booker ( you. ), Encyclopedia of Comic Books and Graphic Novels , ABC-Clio, , 763 p. (ISBN 978-0-313-35746-6 , read online )

- (in) Jon B. Cooke and David Roach , Warren Companion : The Ultimate Reference Guide , TwoMorrows Publishing, , 272 p. (ISBN 1-893905-08-X , read online )

- Gérard Courtial , To meet superheroes , Expanded, , 152 p.

- (in) Marc Dipolo , War, Politics and Superheroes : Ethics and Propaganda in Comics and Film , , 330 p. (ISBN 978-0-7864-4718-3 , read online )

- (in) Randy Duncan and Matthew J. Smith , The Power of Comics : History, Form & Culture , New York, The Continuum International Publishing Group Inc., , 346 p. (ISBN 978-0-8264-2936-0 , read online )

- Dominique Dupuis , At first was yellow…, a subjective story of comics , Paris, plg, coll. “RAM”, , 263 p. (ISBN 2-9522729-0-5 )

- (in) Mark James Rent , A History of Underground Comics , Ronin Publishing, , 3 It is ed. , 319 p. (ISBN 978-0-914171-64-5 , read online )

- Henri The Philippines , Dictionary of comics , Paris, Bordas, , 912 p. (ISBN 2-04-729970-5 )

- Jean Paul Catches , Comics and men: cultural history of comic books in the United States , Nantes, editions of time, , 478 p. (ISBN 2-84274-309-1 , Online presentation , read online ) .

- (in) Ron Goulart, Comic Book Culture. An Illustrated History , Portland : Collectors Press, 2000.

- (in) Robert C. Harvey , « How Comics came to be » , in Jeet Heer and Kent Worcester, A Comics Studies Reader , University Press of Mississippi, , 380 p. (ISBN 9781604731095 , read online )

- (in) Robert C. Harvey , The Art of the Funnies : An Aesthetic History , Univ. Press of Mississippi, , 252 p. (ISBN 978-0-87805-674-3 , read online )

- (in) Jeet lord et knows Worcester (éd.), Arguing Comics. Literary Masters on a Popular Medium , Jackson : University Press of Mississippi, 2004, 176 p. (ISBN 9781578066872 )

- (in) Arie Kaplan , From Krakow to Krypton : Jews and Comic Books , Philadelphie, The Jewish Publication Society, , 225 p. (ISBN 978-0-8276-0843-6 , read online )

- (in) Nicolas Labarre, ” Two Flashes. Entertainment, Adaptation : Flash Gordon as comic strip and serial », Comicies. Graphic culture studies , May 2011.

- (in) Gina Egyptian , The Superhero Book : The Ultimate Encyclopedia Of Comic-Book Icons And Hollywood Heroes , Visible Ink Press, , 725 p. (ISBN 1-57859-154-6 , read online )

- (in) Amy Kiste Nyberg , Seal of Approval : The History of the Comics Code , Jackson (Miss.), University Press of Mississippi, , 224 p. (ISBN 0-87805-975-X , read online )

- (in) Shirrel Rhoades , A Complete History of American Comic Books , Peter only, , 353 p. (ISBN 978-1-4331-0107-6 And 1-4331-0107-6 , read online ) , p. 120

- (in) Chris Ryall the Scott Tipton , Comic Books 101 : The History, Methods and Madness , Impact, , 288 p. (ISBN 978-1-60061-187-2 , read online )

- (in) Roger Sabin, Comics, Comix & Graphic Novels , Londres, Phaidon, 1996.

- (in) Joe Sutcliff Sanders et al. , The Rise of the American Comics Artist : Creators and Contexts , University Press of Mississippi, , 253 p. (ISBN 978-1-60473-792-9 , read online )

- (in) Amy Thorne , « Webcomics and Libraries » , in Robert G. Weiner, Graphic Novels and Comics in Libraries and Archives : Essays on Readers, Research, History and Cataloging , McFarland, ( read online )

- (in) Brian Walker, The Comics Before 1945 , New York, Harry N. Abrams, 2004.

- (in) Virginia Woods Robert , « Comic strips » , dans Ray Broadus Browne, Pat Browne, The Guide to United States Popular Culture , Popular Press, ( read online )

- (in) Bradford W. Wright , Comic Book Nation : The Transformation of Youth Culture in America , JHU Press, , 360 p. (ISBN 978-0-8018-7450-5 , read online )

Related articles [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

Recent Comments