Giuliano’s Sasanide campaign – Wikipedia

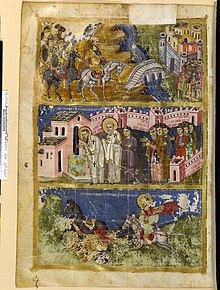

The Giuliano’s Sasanide campaign It was the last military operation of the Roman wars Sasanidi (224-363) desired and commanded of the Roman emperor Giuliano in 363, in order to conquer the kingdom of the Sasanids, at the time governed by the king of the King flavor II. After arriving to the capital Sasanide of Ctesifonte and having defeated the enemy army you, Giuliano was forced to retire, but he died before returning to Roman territory and his successor, Gioviano had to buy the salvation of the Roman army at a high price, and economic and political.

Ammiano Marcellino, a historian who met Giuliano, constitutes the primary source of the countryside: the chapters from the 20th to the XXV of his Achievements They tell the invasion in detail. [first]

Giuliano wanted a campaign against the Sasanids in order to eliminate their threat; For this reason, the emperor came, in the summer of 362, in Antioch of Syria, in order to prepare the countryside.

The real reason behind the Sasanide campaign of Giuliano is the subject of debate in the academic field. The campaign was neither urgent nor necessary: although its predecessor Costanzo II had not signed any peace with the Sasanide King Sapore II, after the victorious countryside in Mesopotamia of 360 the Sasanids had retired to their territories. The Sasanids had even tried to stipulate a peace with Giuliano, who no less refused the offer; [2] Ammiano Marcellino tells of how Giuliano was eager to get victories against the Persians. [3] A further reason could have been the desire to make deeds comparable to those of Alexander the Great; Ammiano himself cites this motivation, [4] Also affirming how all the generals involved in wars on the eastern front could not fail to have Alexander as a model. [5]

A further reason could have been Giuliano’s will to strengthen his link with the army, with a victory that would have increased the prestige of emperor and army and improved the relationship between Giuliano and his generals. The Roman army at the time of Giuliano was in fact divided into two factions: the western one, with soldiers of Gallic origin and pagan faith, such as the officers Dagalaiphus and Nevitta, and the oriental one, made up of Rome’s soldiers of Christian faith. Furthermore, it is possible that the oriental officers, who had a long war experience against the Sasanids, were skeptical against an offensive campaign like that of Giuliano. The demonstration of the fact that the desire to go to Julian’s war was shared only by a small part of the army was that with the progress of the campaign the emperor had to order the execution of some officers and even the decimation of some units. [6]

On March 5, 363 Giuliano left Antioch by moving to the East. The sources report different numbers regarding the strength of its army; However, it was one of the largest operations of late antiquity. [7]

The emperor entrusted the king of Armenia the task of providing him with supplies and auxiliary troops; In Hierapolis Giuliano he concluded a pact with the Arabs. He then went south to the south, along the Euphrates. Ormisda accompanied him, a member of the Sasanid royal family, who had escaped at the Roman court already at the time of Constantine I and who served Giuliano as a councilor.

According to reports by Ammiano, Giuliano was disturbed by negative omens received during the stop in Carre. [8]

Giuliano decided to send a strong contingent to the north under the command of his relatives Procopio and Sebastiano, with the aim of joining the troops of the Armenian King Arsace II and operating in northern Mesopotamia, while he headed on Ctesifonte; According to Zosimo, an author of the 6th century, the procopio contingent was made up of 18,000 soldiers while Giuliano had a strong army of 65,000 men. [9] Giuliano’s advance allowed the conquest of several cities and enemy fortresses, but the emperor was worried by the fact that the bulk of the Sasanid army was no trace; The Persians, in fact, limited themselves to low -intensity but continuous attacks, in order to prevent the Roman soldiers from resting and always keep them on the alert, and prevented Giuliano from putting his hand on the large deposits of material necessary for him.

At the end of May the Roman army finally reached Ctesifonte. However, the impossibility of the success of a direct attack on the capital Sasanide became clear to Roman officers, also because the army of flavor II was given very close to the city and could have been able to reach any time. Giuliano made a decision of consequences at that moment. Since the Romans lacked in the necessary siege machines, it was not possible to take Ctesifonte in reasonable times; At the same time, it was not even possible to resume the same way to return home, as the Roman looting and the destruction of any source of supply by the retired Persians had eliminated this possibility. Although there was a risk that tastes it chased it with the Sasanide army and destroyed it, Giuliano wanted to avoid being surrounded at all costs as he besieged the enemy capital and then decided to move by land to the north of Mesopotamia, to gather with the contingent of Procopio. Giuliano’s generals were against this plan, but the emperor imposed his decision and the Roman army, who had defeated the Persian one before the capital (battle of Ctesifonte), broke the siege in early June and moved towards the inland. In addition, the Romans made another mistake, burning the river fleet that accompanied the army, as it was not considered to have to cross another river. Ammiano describes the difficulties of the retreat, made even more difficult by high temperatures, insects and the inadequate supply of food and materials; The moral of the Roman army was very low. [ten]

On the way back home, the Roman army had to finally face the complete Sasanide army; In the battle of Maranga the Romans were still victorious, but Giuliano died as a result of a wound reported in the clash. A advice of the high Roman officers chose an officer of the guard as successor, Gioviano, who, to the intensification of the Persian attacks and to decrease the provisions replied asking for peace to the Sasanids.

Based on the peace of 363, the Romans ceded the areas beyond the tigers and fifteen fortresses to the Sasanids, including Singara and Nisibis, whose loss inflicted a hard blow to the Roman defensive system; The boundaries between the two states returned to be those preceding the Roman conquests that began with Diocletian in 298. In the following years, the Romans had as its purpose the reconquest of Nisibis.

- ^ It seems that Ammiano has also used other sources, such as the works of Magno di Carre, who came only in some fragments, and of Eutichiano, both used probably also by Zosimo.

- ^ Libanio, Prayers , 18.164.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, XXII.1.12.1.

- ^ Marcellino, XXIV.4.27.

- ^ Robin Lane Fox, “The Itinerary of Alexander: Constantius to Julian”, The Classical Quarterly, New Series , 47 (1997), pp. 239–252.

- ^ Gerhard Wirth, “Julian’s Persian War. Criteria of a disaster”, Julian apostate , Ed. By Richard Klein, Darmstadt 1978, pp. 455 e Segg.

- ^ The literature on Giuliano’s Persian campaign is somewhat vast in every biography of the emperor. See in particular Glen Warren Bowersock, Julian the Apostate , London 1978, p. 106 and Segg.; Rosen, Julian , p. 333 and firm. Paschouds’ comment on Zosimo provides important information on Giuliano’s campaign.

- ^ Pliny the Elder, XXIII.3.3.

- ^ The estimate of the force of the army of Giuliano is based on zosimo (III.12); However, it is not clear whether the 18,000 men of Procopio should be counted separately, and therefore if the Roman army was made up of 83,000 men in total, or if rather Giuliano had with him in his descent on Ctesifonte 47,000 men.

- ^ Ammiano, XXIV.7. By la ritirata if Veda Ammiano, XVI.1 E Seguenti, Rosen, pp. 353 e Seguenti, Wirth, pp. 484 e seguenti.

- Primary sources

- Secondary sources

- Literary works

Recent Comments