History of the ancient Near East

The History of the ancient Near East It moves from the Neolithic revolution, protohistoric phase in which man, also in other parts of the world, gradually perfected the most archaic production technologies. The beginning of the story is traditionally associated with the invention of writing (second half of the fourth millennium BC), but already during the so -called protohistory of the Near East the progressive affirmation of the urban, Templar and Palatine models [first] It represents a brand that characterizes the entire period from the 4th millennium BC. Until the middle of the first millennium BC On the other hand, the role of writing with respect to the “rising” of history is important not so much because it makes sources available again, but because, as Mario Liverani writes, “for the first time we are witnessing the complex interaction of Human groups within individual communities (social stratification, establishment of a political management, socio -political role of ideology) ” [2] .

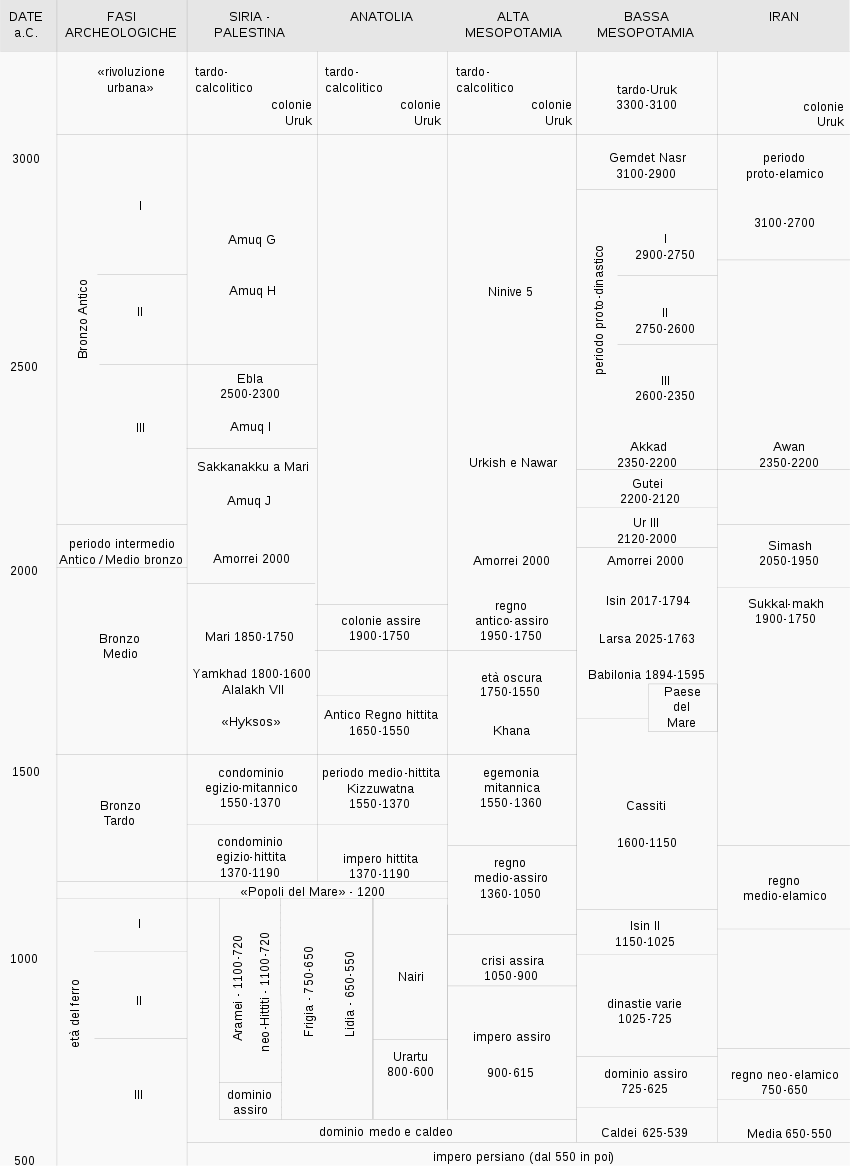

The story condensed in the Near East represents half of the entire documented human history [3] . Conventionally, in addition to the Neolithic Revolution, by an age of the bronze (from 3500 BC), usually divided in an ancient period (in the context of which the “urban revolution”), an average period is marked by a bronze age. (which begins with the collapse of the Ibbi-Sin Empire and the progressive amounts of the Near East) and a late one (which begins with a sort of “dark age”, in the 16th century BC), and then moved to an age of the Iron, which coincides with the arrival of the peoples of the sea (1200 BC ca.).

Periodization [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

An ancient historiography is missing that has left a trace on which to graft the modern historical reconstruction of the Near East. It is a story that rests entirely on primary sources: administrative, commercial, legal documentation, in general in archival function. This documentation resisted the time because they are collected on a support, the clay tablets, which have resisted fires, immersion in the soil and other atmospheric agents very better than other supports (the papyrus, the parchment, the paper) that will come gradually used, in the area considered or elsewhere [4] .

In addition to the light of the Greek-Classic reconstruction, the ancient-oriental historical context has been read through the Bible [5] and indeed the rediscovery of this story has often had as their engine the attempt to reconstruct the historical environment behind the biblical stories [6] .

Approximately, the high limit of the historical context in question can be identified when the written sources see the light, in addition to the purely archaeological ones, while the low limit could coincide with the advent of Greek-Roman sources [7] . Archaeological sources typically present themselves in Monticelli formed by the accumulation of materials produced by the millenary human occupation. Such piles of rubble, which stand out for example in the flood plain, but also in other geographical contexts, are said tell In the span top in Persian e hüyük In Turkish, and these expressions often resort to the names of different archaeological sites (for example, Tell Brak, Tepe Gawra or çatal Hüyük). [8]

A periodization based on political considerations was offered by Van de Mieroop, which highlighted how the city-state represented the predominant political element from 3000 to 1600 BC. Ca., followed by the “territorial state”, between 1600 and the beginning of the first millennium, and then by the empires (axiro first and then Babylonian). [9] Overall, however, the periodization of the history of the Near East depends to great extent on the possibility of accessing the sources. In this sense, the Mesopotamian sources also condition the knowledge we have of “peripheral” cultures, which, as suggested by archeology, must have had a parallel development, not always dependent on the evolution developed between the two rivers. Mesopotamian culture is characterized by uninterrupted continuity, based on the use of cuneiform writing and the preservation of cultural and religious traditions. [9]

|

Chronological problems [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

For the ancient Near East, of course, archaeological dates (location of finds both of each other, but also absolute dating, that is, in relation to the present) and cultural dating are naturally followed. The former are generally based on vertical stratigraphy, the latter on the horizontal stratigraphy (the one in use for the necropolises, for example) and on the typological classification. The latter must necessarily play a secondary role. The absolute dating can be substantiated with the discovery of textual documents in a layer or with one of the various physical-chemical methods with which some materials can be dated, in particular organic ones. [11]

For the period from the end of the fourth millennium BC In the middle of the III, the documentation is almost only archaeological (the written documents of this period are almost all of an administrative nature), while buying a more articulated character for the period from the second half of the third millennium to the first millennium BC: they were Retained real inscriptions, calendars, chronicles, annals, legal acts and real lists. [twelfth] Other important sources for the reconstruction of the Assyrian and Babylonian chronology are the so -called Synchronic history (which tells of the relationship between Assyria and Babylon in the first millennium BC, suggesting many important synchronisms) and Babylonian chronicles ; the latter (now preserved in the British Museum) are based on Astronomical diaries and collect events from Nabonassar (747-734 BC) to the Hellenistic period. [twelfth]

The chronology of the 1st millennium BC It is known with sufficient safety and is based on a good documentation, which includes the so -called Ptolemaic canon , a real list drawn up by the Greek astronomer Claudio Tolomeo in the second century AD, which starts from 747 BC. Another certain reference is an eclipse that occurred on June 15 763, which allows you to absolutely date a long sequence of eponymous axes officials (i Limmu ). The chronology of the first centuries of the first millennium BC It is less certain and going back in time the situation becomes even more uncertain. [13]

Ancient-eastern cultures felt the need to set their own chronology of events (role played by scribes and priests), but in often incompatible ways with modernly understood historiography. The eras in use in Mesopotamia were relatively short and referred mostly to the intronizations, so that each city-state could have its own. Thus, for example there is a document dated “day 4, month III, year sixth of Nabuchadeyer”, which risks, as it is, to remain unrelated to the modern reference systems. [14]

The dating systems in use between the Mesopotamian populations were essentially three: [twelfth] [15]

- the identification of the year through the name of an eponymous official, said glue (So in Assyria throughout the course of its history).

- The one -year denomination with reference to an event, such as eg: “the year in which the walls were built in the city X” (this system, called “of the name of the year” – year name In English – it was in use in the Sul Sammeric South and then in Babylon until the middle of the second millennium BC).

- the system of the years based on the enthusiasm of the kings (system in use in the Babylon Cassita and also subsequently).

Texts like the Real Sumerian list (but also the Babylonian Royal List and the Royal List Assira , from the rear era) came fragmented and incomplete. Then there are also material errors, findable when it is possible to compare different reproductions of the same list. The tampering are still more decisive, intentional in greater or lesser extent, often of political-ideological flavor: some kings or entire dynasties are expunged, some dynasties that exerted their power in the same period are acrytically in sequence. The insertion of mythical-legging elements is more easily controlled, in particular at the beginning of these lists. [16]

The chronology that has been able to extrapolate from the data available is sufficiently precise for the period 1500-500 BC. And indeed, for the first millennium BC Historians have Babylonian chronicles and annals axiris that are more precise than the lists. [16]

The Royal List Assira It is the best preserved dynastic sequence and the longest. Yet, in the middle of the second millennium BC One is produced, caused by gaps in the text and by different overlaps of Babylonian dynasties. For the period 2500-1500 BC This hiatus is measurable in tens of years, but it becomes more full -bodied as it is relegated to older times. The attempt to fix the hiatus in relation to the period around the middle of the second millennium BC, referring to allusions to astronomical phenomena contained in paleo-babylonian texts (period of admiral, king of the first Babylonian dynasty: 1582-1562 BC, according to the Short chronology; it is the so-called “tablet of Venus of Admiral”) has not been successful, since astronomers have not found an agreement on the interpretation of these allusions. Based on the uncertain indications of astronomers, three different chronologies were determined: one, so -called “long chronology”, a “medium chronology”, a “short history” and “ultra -tetrobress chronology”. That “average” is the greatest consent. The most solid chronology is that relating to Mesopotamia: those of the surrounding areas rely on this. [17]

Among the royal lists, it is possible to distinguish those in Sumerian and those in Accadico. In Sumerian we only have the Real Sumerian list and the Reale di Lagash list . Many more are those in Accue: the Royal list of Larsa , the Qveraeeerumee the pate in , the Babylonian Royal List , the Royal List Assira And the assiraia Synchronic list , so called because apparently tries to establish synchronisms between the Assyrian and Babylonian kingdoms. There Babylonian Royal List It consists of three different documents (indicated with letters A, B and C). Then there are three different main specimens of the Royal List Assira : the Royal list of Nassouhi (Nakl), la Real list of KhorsaBad (Khkl) and the so -called Seventh Day Adventist Seminary King List (SDAS). [18]

Then there are later lists: the In duae to the body you are. (UKL), kept at the Iraq Museum and therefore cataloged to the number IM 65066, reaches the third century BC; there Royal list of the Hellenistic period , preserved in the British Museum and therefore cataloged to the BM 35603 number, it reaches up to the second century BC. [18]

History of archaeological discoveries [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

In the mid -nineteenth century, the opposing imperialisms of France and Great Britain pushed the two countries to concentrate in the northern Iraq, the region of ancient Assyria, where the most sumptuous monuments emerged. Only at the end of the nineteenth century archaeologists dug in the southern Iraq and tracked down the Summera civilization. [19]

Some events of the twentieth century also had a dramatic impact on archaeological research: the Iranian revolution of 1979, the first and second Gulf war (1991 and 2003), the Syrian civil war, which broke out in 2011, forced archaeologists to go in areas first considered peripheral. The archaeological discoveries that occurred there have contributed to reconsider the historical centrality of Mesopotamia. [19]

Epipaleolitic [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

Robert John Braidwood distinguishes two phases:

In the first phase, the settlement is still in caves and the communities, following the animals that support their diet, are made up of 40-50 individuals at most. Men have not yet developed any production or conservation technique of food and subsistence remains a daily challenge. [20] The man tends to hunt more minute prey (gazelles, sheep, goats), but does not do it more indiscriminately: rather attempts to safeguard the consistency of the flock, through a form that is of control, even if not yet direct. [20] The collection of graminaceae and legumes produces an discharge and selection of seeds. [20] Lithical industry heads towards microlitism. The first pestelli appear. [21]

In the second phase, the talented of the flock begins, with the consequent use of milk and wool, and the first cultivation experiments. The man begins to gradually abandon nomadism, gradually stable in the low mountains, next to a strong variety of ecological units. [22]

Neolithic [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

Aceral Neolithic [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

The period of the aceramic Neolithic (approx. 7,500-6,000 BC) can be understood as an almost “full” Neolithic [24] . The total sedentary lifestyle, in raw or mud brick homes, can be said. The houses have now quadrangular shape, a format intrinsically open to new aggregates. The inter -family cooperation within the villages is very important in this phase, made up of several hundred individuals. [25]

The inhabited nuclei are completely autonomous, but the contacts between them expand and also cover distances of discreet length as regards the availability of certain materials (hard stones, metals, shells): in particular, a trade is developed by the ‘Ossidiana (from Anatolia and Armenia), while the shells come from the Mediterranean, from the Red Sea, from the Persian Gulf. In short, we exchange valuable materials and slightly clutter (not the food, therefore) [25] [26] .

The full Neolithic and the crisis of the VI millennium [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

Legend (from Sudest to the northwest approximately):

Haggi Muhammad culture

Culture of Samarra

Halaf culture

Culture of Havena

Culture “Halaf type”

Anatolic ceramics

Amuq D and Neolithic Ceramic B Palestinian

(Biblo area): average Neolithic of Biblo

The period from 6000 to 4500 BC It is generally indicated as “full Neolithic”. The affirmation of the new characters in the subsistence economy (agriculture and breeding) is accompanied by new manufacturing techniques (weaving, processing of ceramic and pounded copper) and by the improvement of the already existing ones (arrow tips, sickle, tools for the processing of the skins, for shearing and slaughter).

The ceramic, in particular, used to cook and to consume food (and more rarely liquids), plays a very important role in this phase, especially as regards the start of extensive cultivation. [27]

The breeding focuses on dog (used for defense and hunting), Caprovini, pigs, cattle and donkeys. [28]

The inhabited people begin to spread from the pedestrian areas to the Iranian and Anatolian highlands and, finally, the Mesopotamian plain come to populate [29] .

Irrigual agriculture, grinding seeds and food conservation techniques are the most important moments of an economy now almost exclusively on agro-pastoral basis. However, the collection activity continues and continue to be always practiced hunting, fishing and collection of molluscs and crustaceans. [29]

In the first half of the 6th millennium, we meet a phase of arrest or crisis, marked by the sensitive decrease in archaeological data (crisis perhaps attributable to a period of drought, resulting from the climate change that occurred around 10,000 and which brought an increase in temperature) [30] .

Relations between community: war and trade [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

The Neolithic “colonization” leaves large residual spaces, dedicated to hunting and harvesting. A low conflict between the communities is assumed, since the weapons received do not denote a typological differentiation between hunting and war. [thirty first]

Nothing is known about language, me is presumed to be a certain differentiation and area correspondence to the historic phase. The correspondence between culture, language and ethnos It may have been greater at this seminal phase, while in the historical era it tends to be nothing or irrelevant and, at the limit, misleading. [thirty first]

As for trade, as mentioned, Neolithic technology is not able to support transport of bulky materials or food. Precious materials are traded (in the proportions of the time). It was possible to reconstruct the trade of Oxyidiana, due to the different chemical composition which it has depending on the place of origin (different quantities of barium and zirconium). [32]

Calculcolic [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

The first signs of a transition from the protohistoric to the historical phase consist in the construction of buildings that seem to be dedicated to only cult (but they are not real temples). In this respect, the culture of Ubaid is particularly significant, (which takes its name from the Ubaid Guide website, in the lower Mesopotamia), a chronologically very consistent culture (in fact lasts from 4500 to 3500), at the beginning of which the Start of the local Calcolithician. It is at this stage that a first infrastructure accommodation of the alluvium takes place. In the late phase of Ubaid culture, levels 7 and 6 of the Temple of Eridu are placed, in which the standard model of the Mesopotamian Templar building for three thousand years will be formed. Funeral equipment suggest a seminal social stratification. [35]

The Uruk period (from 4000 to 3100 BC ca.) takes its name from the Uruk guide website. It is at this stage that an organizational “leap” is identified: the transition from the Ecological Niche Pedemontana, in which very different environments are interfacked at close range, to a decidedly wider, that of the alluvium, it seems the fundamental reason that pushed the Human communities to organize themselves at congruous levels: tigers and Euphrates offered a much richer collected potential, but on the other hand, a strongly coordinated channel work was necessary to allow the transition from the “dry” agriculture of the pedemony to the irrigation of the irrigation of the irrigation of the irrigation of the ‘Flood: the first obeys rainfall, the second is to an extent greater result of human work, because it conveys the waters where it is necessary and drains excess quantities. The flood, which in the period of the first Neolitization, was still far from the fulcrums of technological and settlement development, during the calculcolicist and in the transition to the early Bronze Age it becomes the central pole and will remain for all preclaxic antiquities, albeit in relationship dialectical with the semi -harmful areas and with the nomadic element that lives them. The culmination of the “urban revolution” of Lower Mesopotamia is to be placed between 3500 and 3200 BC. [37] : in this phase, corresponding to the late-Uruk, the sedentarization of agricultural producers assumes significant proportions never found before; It should be noted that “the great organizations of the first urbanization are constituted in the absence of the writing tool: they are their needs that lead to its introduction” [38] .

The first urbanization [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

The North is somehow “colonized” by the Uruk model, with the creation of settlements aimed at supporting, apparently, southern trade (a substantially river trade). Pure, it is already present and an autonomous culture of the North remains in life, which was reflected (and will reflect) in a different political model, substantiated by a different relationship with the territory. [39] In particular, between the South (Sumer) and the North (Akkad) [40] :

- The territory of the South is more subject to swamping; It is organized centrally (“Templar colonization”)

- In the north, water flows are more easily controlled (to the detriment of the valley on the valley); The role of “free” is more incisive, given the “noble” nature of the command

In essence, settlements such as Susa or Habuba Kebira seem to be real “colonies” of Uruk, while in several coeval centers, in the north, the relationship with the nomadic-pastoral element defines a different political panorama [41] . These are the centers of Subartu (La Futura Assyria) and the “Triangle of the Khabur: the Tepe Gawra site represents for the North what Uruk represented for the South. When the” colonization “arrives there, this is implanted on An important culture, while, always in the North, there are also cases of real foundation from nothing (the same Habuba Kebira and Gebel ‘Aruda [41] ). Another important center of the North is Nineveh. [41] Tell Brak is instead the most relevant site of the Khabur triangle (relevant his “temple of the eye”) [42] .

As for Palestine, the first urbanization was just involved [43] .

The ancient bronze of the Near East ranges from 3000 to 2000 BC [ten]

The crisis of the first urbanization [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

In its later phase (end of the fourth millennium BC), the culture of Uruk suffers a strong contraction, which sees the disappearance of some centers that refer to it. The reasons for this crisis are not entirely clear: Liverani hypothesizes a question of performance of the crops, more contracted outside the alluvium. [44] The scope of this crisis, in the absence of written documentation, can only be evaluated in relation to material culture (especially ceramic production): in any case it happens a regionalization (in the face of the strong homogeneity represented by the type-ubaid settlements). The Uruk phase follows the so-called Gendet Nasr period (corresponding to Uruk 3), which takes its name from the Gemdet Nasr guide site: this phase is called “proto-literate”. It follows the period called “Protinetica”, with a first recessive phase (proto-ending I, 2900-2750 ca.). [45]

The protinastic phase [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

With this phase we enter the third millennium BC The protinestic phases II and III, after the first recessive phase, are of expansion, both demographic and technological. The regionalization produced by the crisis of the first urbanization is now developed in a city-state system: among these, Uruk, Urk, Eridu in the South, Lagash and Umma on the Tiger, Adab, Shuruppak and Nippur in the central area, kish to the north, and Eshnunna in the far north. [forty six]

| Proto-ending period in Mesopotamia [47] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Proto-ending i | 2900-2750 CA. | |

| Proto-ending II | 2750-2600 shifts. | |

| Proto-ending III | a | 2600-2450 shifts. |

| b | 2450-2350 shifts. | |

The second urbanization [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

The second urbanization in Syria and Alta Mesopotamia [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

The panorama valid for the first urbanization (a southern culture that is implanted on a northern substratum of noble and pastoral nature) is repeated on the occasion of the second urbanization [39] . However, it must be said that this second urbanization has greater diffusion than the first and is implanted in a more stable and significant way: the two fundamental settlements (true “bridge heads” of the South in the north) are seas on the Euphrates and absur on the tiger: around To these settlements, direct Sumerian emanation, there is a whole constellation of settlements (cities or villages) which are instead issuing the northern culture: these foothills are based on “dry” agriculture (which is based on rainfall) and on Caprovini breeding (in the south much less significant). The influence of the South is felt on the administrative level, but the material culture is different and is based on a different environmental background. A certain cultural unit of the pedestrian’s cultural unit can be assumed: they range from the anti-tauro pedonmonte to that of the northern Zagros. With the appearance of a written documentation, Hurrite and Semite populations will emerge in these areas (the first in the most Nordic band). [48]

In the long run, this northern settlement band will flourish in proto-ending II (2750-2600) and III (2600-2350) and then up to the Akkad empire (2350-2200), the Gutea invasion (2200-2120), The third Ur dynasty (2120-2000), while there is a declining phase in the middle bronze and further contraction in the late bronze. [49]

The second urbanization involves a solid diffusion of the “city” model, and with it of the institutions and characteristics that are accompanied by it: a systematic use of writing (obviously limited to a specialized elite, that of the scribes), centralization of the command, hierarchy of the settlements and a strong social stratification (as shown in the widespread trade in valuable objects, illuminated by the discoveries of the Ebla shopping center, in Syria). [50] It is possible that suddenly the Institute peak of the third millennium BC It corresponds to a climate phase richer in rainfall, because subsequently, when the climatic conditions worsen, the foothills of the foothills (the “high country”) will demonstrate that it cannot support too dense urbanization. [49] There is no archaeological evidence of the appearance of writing in high Mesopotamia in this pre -racing phase, but the richness of the Ebla archives made that also in the “high country” the writing was used significantly. [51] Moreover, the Ebla archive refers to one a -Bar-Sìla, probably ASSUR, for which we speak of a “Treaty between EBLA and ASSUR”. If an absur is, an international commercial system would be configured, with two main streets, that of Ebla (Alto Eufrate, Syria) and that of ASSUR (Alto Tigri, Anatolia), whose mutual interference would be at the origin of the decision to regulate it use through a treatise (in particular, the treaty allows the Assyrial merchants to use the kāru Eblaiti). The way of Assur so hypothesized is also the same that will manifest itself in the Paleo-Assiro trade phase. [52]

The documentation joined by Mari (city well present in the tablets of the Ebla archives) and by its so-called “Palazzo Presargonide” (perhaps already of the proto-ending IIIA), the various temples, including that of Ishtar, is also important. Mari appears to be a direct Sumerian emanation, but the documentation reveals a largely semite honor and the language is the same as in Ebla, a “pre-amorrhea” Semitic language. [53] A fundamental document to discern the relationship between Ebla and Mari is the so-called “letter of Enna-Dagan” (however it is not clear whether Enna-Dagan was a king of Ebla or, as is more likely, a king of seas). Overall, the commercial role of Mari, passing on the Euphrates between Mesopotamia and Syria as is Assur for Tigri, is in substance dependent on that of Ebla. Although the overall picture of this historical phase is very dark, it is possible to hypothesize a certain competition between the two cities, which may have had military implications. [54]

The second urbanization in Lebanon and Palestine [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

At the end of the Calculotic (end of the fourth millennium BC), Syria-Palestin experiences a fragile prototourban experience with the Giawa site, in today’s Jordan [43] [55] . It is only during the third millennium BC (especially in the middle of the millennium, coinciding with Ebla’s apogee) that the urban model emerges strongly in these areas, moving from north to south, reaching first on the coast and on the valleys with dry agriculture, subsequently on the hills. In this period (corresponding to ancient bronze III), Palestine touches a demographic and vast peak is also the extension of the human penetration area. [43] In the past, the hypothesis of a dense migratory phenomenon from the north has been advanced. In fact, the ceramic types of est-anatolic inspiration are recognizable (in particular in the type of Khirbet Kerak, on Lake Tiberiade), but these are models reworked by local populations, in the context of a non-sudden development. [43]

The cell of this Institute development is the pastoral tribe, with a stunted agriculture and dependent on capricious rainfall. The most important resources are represented by Lebanon’s cedars, by the copper of the ʻaraba, Turquoise and Cornalina del Sinai [43] .

In this phase the urban center of Biblo (with evidence of imports from Egypt) is already certified and perhaps the Foundation of Ugarit is also of this time [43] . Other important centers are the already named Khirbet Kerak (Bet Yerah) and Megiddo, located in the Valleys, Gerico, located next to an oasis, ʻai and Tell Farʻah on the hills. Subsequent are the settlements of Tell ʻareyni and Tell ʻArad (in the Negev). [56]

These are medium -sized centers compared to the Syrian and Altomenasopotamic ones. The fortifications of all these centers testify to a high conflict between them. They housed public buildings, as is the case with a building in Megiddo, of a Silo in Khirbet Kerak or the so -called Temple of Reshef in Biblo. Overall, the temples of the area are minutes and to a single environment, very different from those of the Mesopotamian alluvium, with which they evidently did not share the marked propensity for political and commercial activity. [56]

The Palestinian centers are also documented by texts from Ebla and Egypt of the ancient kingdom (Egypt). However, we do not have a picture of domain relationships. Moreover, the EBLA archive, which deceives a series of dense commercial relations around the ancient Syrian city, does not embrace, with its references, the commercial network existing south of Biblo and Hama: it seems that the Palestinian centers gravin more on Egypt, but it must be said that vases with Egyptian cartouches (of the IV and VI Dynasty) were also found in Ebla (as well as Biblo herself) and it is possible that Biblo has played a role in this trade. There are several prestigious assets that have been found in Egypt or Ebla and which are the result of these trade (understood as regional gifts): lapislazzuli in Egypt and Ebla gold, of Egyptian origin or perhaps also of Eastern Africa. [56]

In addition to the resources already mentioned (cedars, copper, turquoise, cornalina), the attention of Egypt to Palestine and Lebanese coast is aroused by olive oil and wine (trades in the jars of typical Palestinian invoice then found in the necropolis of the ‘era of the ancient kingdom), as well as from the resinous essences that the premises derive from the conifers. The Egyptian attitude is not set to a commercial equality: the relationships with the local elites were probably based on an “unequal exchange”, so these, in exchange for access to the goods, obtained prestigious objects (such as apotropaic scarabes) . And Egypt is likely to also use the strength to access Palestinian resources. [57] The Egyptian reinforced intervention was often addressed to the repression of nomads (called Shasu, ʻamu or, with more generic terms, “the wild”, “those of the sand”), seen as a disturbance of the commercial practices that Egypt entertained with the permanent populations [58] , but there are also sorties in urbanized areas, as the tomb inscriptions of UNI or a parietal representation in Deshasha attest, where the siege of a fortified Palestinian city depicted. But it is not yet an interest in direct management of the territory, as regards the protection of the ways of access to resources. [59]

The second urbanization in Palestine and Lebanon enters a certain point in crisis, but it is neither the pressure of the Akkad empire nor the much more soft one of the Egyptians to determine this merger. It is an internal crisis, probably determined by the insustibility of a demographic pressure not adequately supported by the resources of the territory and by the technological possibilities of the ancient bronze. It will then be the nomadic element that, in the medium bronze, will be able to bring a more stable urbanization back to Palestine and in the surrounding areas. [60]

The Akkad Empire [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

The Accadi, a semite population [sixty one] Present in Mesopotamia since the proto-ending II and III (2750-2350 BC, according to the average history), they were a nomadic population, from tradition, according to tradition, from the Siro-Arabic desert [62] . They represent the conspicuous historical manifestation of a long -term phenomenon, that is, the “cohabitation”, in the Mesopotamian field, of Semiite populations with the Summera Civilization, cohabitation that dates back to at least at the fourth millennium BC. [63] The Empire they constituted (called “Akkadian” or “of Akkad”), founded by the The new man Sargon, represents the most important unifying initiative up to that moment experienced in Mesopotamia.

In addition to Sargon (2335-2279 BC), the other great important figure in the approximately 150 years of life of the Accounting Empire is Naram-Sin, who reigned from 2254 to 2218 BC. [sixty four] Both great kings remained impressed in the memory of the Mesopotamian people very long, but Sargon as a positive example and Naram-Sin (undeservedly) as a negative example [65] .

The cause of the collapse of the Akkad dynasty is generally attributed to the invasion of the Guutei, a mountain population originally from Luristan. It is likely that their domain extended near their region of origin: this meant a certain autonomy for the South (Sumer) and this condition will be the prelude to the reconquest of political power, with the so -called Sumerian rebirth. [66]

L’eta neo-sumerica e ur 3 [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

The neo-suumeric age or Sumerian rebirth (end of the third millennium BC) sees a return of initiative by the cities of Sumer (Bassa Mesopotamia). During the Guuteo domain, the Sumerian cities-state had enjoyed a certain freedom and this also explains how the Guutei could have controlled the area for about 100 years. The Guutei disappear almost in nothing after a war episode: Utu – Hegal, king of Uruk, beat the Guteo army sent by King Tigan in the open field, who fled to Durum, where he ended up killed. Utu-Hegal obtained hegemony on the other cities-states for a short time, but soon he was barely undergone from Ur-Nammu, king of Ur. A new dynasty stands with him, the third UR dynasty, which will have great meaning in the subsequent Mesopotamian events. [sixty seven]

The most important kings of the Neo-Sumeric Age are, in addition to Utu-Hegal (2120-2112 BC) in Uruk and Ur-Nammu (2012-2095) in Ur, also Shulgi (2094-2047) a (successor of Ur- Nammu) and above all Gudea (uncertain dating, probably contemporary of Ur-Nammu [68] ) In Lagash. Last re di ur di ur iii è ibbi-sin (2028-2004). [69] [70]

With the reconquest of independence, the sumercian cities-state resumed their state tradition, with the next places to dominate individual cities. Among these, the Real Sumerian list It emphasizes Uruk’s fourth dynasty, while the most relevant archaeological remains concern the second Lagash dynasty (with the Ur-Baba, Gudea and Ur-Ningirsu kings). The literary texts and votive statues relating to Gudea are particularly significant, which is the best known Sumerian king. [71]

The medium bronze of the Near East goes from 2000 to 1500 BC [ten] After the destruction of the city of Ur due to the elamites and of the amorrei, these will kick off the so -called amorrei kingdoms, that is, have been governed by dynasties of Amorrhea origin.

The crisis of the second urbanization [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

The period of Isin and Larsa [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

The so-called isin-work period goes around 2000 to 1800 BC. It takes its name from two cities of the lower Mesopotamia which (in sequence) dominated the area: Isin (in particular with his (first dynasty) and then Larsa. [72]

The collapse of the third UR dynasty did not result in an immediate political fragmentation. The cities-states, although in conflict, recognized that they were part of a system in some way common, centered around Nippur, a sort of religious capital, whose control allowed a sovereign to boast of the title of King of Sumer and Akkad (regardless of the real scope of its power [seventy three] ). It is in this phase that the idea of a royalty that passes through cities in the city is consolidated and develops the Real Sumerian list [74] (or rhymes it, if it dates back to UR III).

The kings of the first Dynasty of Isin tried to absorb the trauma of the fall of Ur (but also other elements of discontinuity, such as the transition from Sumerian to the Accadeus and the amounts process) through an ideology of continuity with the kings of Ur III (divinization of the king, title, royal lists aimed at highlighting the direct succession). This continuity was also effective. [75] Already with Ibbi-Sin the imperial system of UR III could only leave more autonomy to various centers, including Isin, Larsa, Uruk, in the North Babylon (whose stratigraphic levels Paleo-Babylonian are not accessible), Eshnunna on Diyala and Der On the border with Elam. At the same time, three centers that had represented important border cities (Mari, Assur and Susa) were consolidated as large formations of large courses. [76]

In Larsa, after a series of short kingdoms, a dynasty was affirmed that reassembled in Kudur-Mabuk, perhaps an elamite based on Mashkan-Shapir, the easternmost of the cities of central Babylon. Kudur-Mabuk managed to install his son Warad-Sin on Larsa’s throne. Upon Warad-Sin’s death, the throne was occupied by the brother of these, Rim-Sin. [seventy three] In 1793, the only rival city remained was Babylon. In 1792, Hammurabi rose to the throne of Babylon. [seventy three]

With the Isin-Larsa period, it emerges alongside the traditional documentation of the great Palatine and Templar organizations a documentation (especially of a legal nature) relating to “private” initiatives in the field of agriculture. Also in the commercial field (as in the case of the sections that connected UR and Dilmun) a private initiative is forming (in particular in the Larsa phase), similar to the paleo-absir trade of the Far away Anatolic. [77]

Origins of the Assyrian state [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

The Palaces of the Middle Euphrates at the time of Mari [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

Mari was an ancient Summe and Amorrita city, located 11 kilometers north-west of the modern city of Abu Kamal, on the western bank of the Euphrates, almost 120 km south-east of Deir El-Zor, Syria. It is thought that it has been inhabited since the 5th millennium BC, although it prospered from 2900 BC. Until 1759 BC, when he was able to sack Hammurabi.

Yamhad [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

Yamhad was an ancient Amorrita kingdom, where a conspicuous Hurrite population also settled, influencing the area with its culture. The kingdom was powerful during the medium bronze age (1800-1600 BC approx.). Her biggest rival was Qatna further south. Finally, Yamhad was destroyed by the Hittites in the 16th century BC.

Hammurabi [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

Intervention of the Hittite State [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

Within a fiftieth anniversary (ca. 1650-1600) the Hittites, led by the two King Hattušili I and Muršili I, became the protagonists of the history of the ancient Near East.

They spread on the Siro-Mesopotamian bassopians and ended the states of Yamkhad and Babylon. During his second year of Kingdom Kattushili launches his first attack against Alalakh, Aleppo’s vassal, destroying it. During the sixth year and following the Hittite king he went down to the south of Tauro, destroying several cities but had to stop at Urshum. Upon Kattushili’s death, the work was continued by the adopted son of the latter, Murshili I who descended to Syria defeating Yamkhad and his allies. Strengthened by his victory, he went to Babylon by looting it and thus ending the reigning dynasty. Murshili’s drawings, however, were not so ambitious, so he left Babylon to concentrate on Syria [78] .

The “dark age” and the “peoples of the mountains” [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

The late bronze of the Near East runs along the second half of the second millennium BC, from 1500 to 1200 BC. [ten] , and happens to a relatively less documented era, so much so that the historiographic tradition spoke for the 16th century BC. of a “dark age”. In particular, for a long time there has been talk of an introduction of new Anatian and Iranian populations (called “peoples of the mountains”), mostly interpreted as of Indo -European origin. The appearance on the nearby-east scene of Hittites, Hurriti and Casiti was interpreted as a unitary phenomenon, in spite of the fact that these penetrations developed along a large span of time and despite the clearly not Indo-European character of these peoples. In fact, the ittitis have been present on the Anatolian plateau since the end of the third millennium BC. The middle kingdom is already constituted in the late paleo-babylonian age and seems indeed in decline in the 16th century. There are also traces of the Hurriti that come back to the middle of the third millennium. The cassites are instead, like Gutii and Lullifiti, populations originally of the Zagros Mountains: their grip of power in Babylon does not derive from a migratory, but political phenomenon, with an ethnic minority which, even in power, certainly does not affect the prevalence of the Babylonian element. [79]

The transition between medium and late bronze takes place without strong discontinuity, unlike the transition from ancient to medium bronze, which he had seen, at the end of the third millennium BC. The coming of Indo -European people. Between medium and late bronze material culture does not change, while there is a contraction in the urbanization process (similar to that found at the beginning of the second millennium), which concerns in succession the medium euphrates, the high Mesopotamia, the Syrian planking , transjordan. The semiaride areas, which had also been central to the development of ancient and middle bronze, are gradually abandoned, to leave room for a lighter occupation, conducted by seminomad shepherds. So it is, for example, for the ancient centers of Mari, Tuttul and Terqa on the Middle Euphrates, Shubat Enlil on the Khabur or Ebla and Qatna river in Syria. The centers supported by richest rainfall keep better, in particular those at the sea or rivers. [80]

The new technologies have their fulcrum no longer in low Mesopotamia, for two millennia at the forefront, but in high Mesopotamia and in Syria: the talling of the horse is mediated in the Mitannic environment, the processing of the vitrea pasta is typical of a band that It crosses Alta Mesopotamia, Syria and Palestine, and that of the purple in the Siro-Lebanese coastal strip. [81]

The advent of the horse in the Near East [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

Certainly new there is the recurrence of Indo -Right Languistic elements, as in the Opinimasti of Mitanni and other connected kingdoms, and above all in the terminology linked to the breeding and training of horses, used now to tow light two -wheeled wagons. For the onomastic, names are conspicuously related to the ancient Persian and Sanskrit: Shuwardata (‘given by the sky’), Biryashshura (‘Hero of value’), indicated (‘Supported by Indra’), but also Teonimi as Indra, Mithras, Varually, Nashatya (invoked in a treatise between Khatti and Khurri), and then Shurya, solar deity of the cassiti, corresponding to the God-Sole Sūrya dei Rigveda . [82]

The appearance of Indo -Diranic Terms is attested in particular by the treaties dedicated to the training of horses, such as that attributed to a Kikkuli of Mitanni. It is the case of Ashušanni (‘Horse breeder’; Sanskrit is compared Aśvas , ‘horse’), A neighborhood (‘charioteer’?), maryannu (‘fighter on the cart’; in Sanskrit Marya is for ‘young’), Babrunnu (‘brown-red’, with reference to the color of the horses; in Sanskrit babhru , ‘red-brown’), barittannu (‘Gray’, in Sanskrit Palitá , ‘grey’), pinkarannu (‘Fulvo’, in Sanskrit will drip , ‘reddish’), Aika-reporter (‘A Giro’, from Sanskrit to , ‘one’ and the ancient Iranian word VARTANÍ , ‘Giro’, ‘Path’, and other numbers appear in the same context: such- , panza- , Shotta- It is Nā-repugnance , from Sanskrit wisdom , Lord , saptá , nava , respectively ‘three’, ‘five’, ‘seven’ and ‘nine laps’). [82]

This Indoiranic layer comes from the East and is distinct from the “Anatolica” Indoe European, which from a point of view of linguistic geography is older. In any case, these are not mass migratory phenomena, with waves of Indo -Stranol tanks aimed at conquering, thanks to the superiority of horse -drawn floats, the whole Near East up to Ejection, as has been interpreted in relation to the Hyksos. The advent of the Hyksos is previous, while Mitanni, often interpreted as the maximum state realization of the Indo -Right Peoples, is actually the result of the political unification of Hurrite populations. Instead, it is the spread of the new technology that brings with it a sort of “onomastic fashion”. The use of the horse and the light two -wheeled two -wheeled chariot is originally from Central Asia, where the political void produced by the crisis of the second urbanization had favored the advance of peoples with a marked pastoral and warrior character. The new technology, which bursts in the Near East to the middle of the second millennium BC. And it quickly reaches Egypt, it is still adapted to the needs of complex urban companies. [82]

The zootechny of the Near East exploited some equids from the Neolithic revolution. The donkey ( Horse donkey ) It was the normal Soma animal. A wild variety, the onagro ( Horse hemionus ), was used to tow four -wheeled wagons, thanks to its greater robustness. The greatest difficulties related to the training of the wild horse had relegated this animal to the margins of common use in the Near East at least until the middle of the second millennium BC. Although certainly isolated cases of paleo-zoological attestation, the historical marginality of the horse also transpires from the marginality of the references in the texts. Not surprisingly, in the sumera language the horse was said anchee , ‘mountain donkey’, and therefore intended as an exotic variant of the most attic donkey. [83]

As for the wagon, it had always been used above all to transport goods, thanks to the use of four full wheels. Its transformation into a light two -wheeled chariot first has a relevance on the war. In the third millennium and in the first half of the II, the battles resolved with Campali clashes between infantry units, which were measured in body to body with short weapon, preceded in some cases by the launch of javelin and arrows. The new type of war instead provides for the charge of wagons against other wagons or against the infantry lined up. The cart, which is normally guided by an auriga and houses an archer, is used as a mobile platform for the launch of arrows, as a tool for loading (even if this use is not accepted by all scholars), as a means of chasing i Fang on the run. Infantry and carriage are manifested as separate bodies, with different military and social prestige. Then there is a hunting use of the light chariot, with limited repercussions on the political level, but certainly of symbolic value, especially if the king is conducted. [83]

In the new bodies of retirements, aware of being decisive for the outcome of the battles, a sort of heroic ideal spreads, which has courage in its center. This ideal binds the king and his own maryannu , and transpires into literature and figurative art, from Egypt to Babylon. The tanks are used full -time directly from the crown: they are granted to land lots, equipped with colonists, where horses and aurighi prepare to provide military service to the king, according to forms approximately similar to medieval feudalism. Before now, it had never happened that a military body assumed the same importance as administrators, scribes, priests and merchants in nearby-horror society. [83]

Vitrea and purple pasta [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

While agricultural, metallurgical and ceramic techniques continue for internal lines, elements of novelty are detected in the field of “chemistry”. For example, it begins to produce a vitreous, opaque and colorful pasta, with which miniaturist objects are made (a vitreous paste was already in use in the medium bronze, but was used only to surface terracotta objects). Such vitrea pasta, called Makkah in western Semitic e eḫlipakku In Hurrita, it was made up of sand, vegetable ashes and mineral dyes, treated with different baked cooking. The Makkah It was an artificial substitute for lapislazzuli and other hard stones, whose traffic was in crisis for the inaching decline of the Iranian plateau. The texts end up distinguishing between a “mountain”, that is, authentic lapislazzuli, because they are extracted, and a “oven” or “boiled” lapislazzuli, that is, the semi -priest imitation. [84]

Fabric dyes also develop, both mineral and vegetable. Remarkable is the case of purple, an animal coloring, mucous secretion produced by the hypobranchial gland of molluscs mostly belonging to the Muricidi family. The manufacture of perfumes and spices also develops, the latter used in the medical field rather than in the culinary field. [84]

Treatise [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

New technologies are illustrated in works that are characterized as real treaties. Previously, the scribes had dedicated themselves only to the treatise relating to medicine and mathematics: the new treatise has a technical-practical flavor, well distinguishable from the Babylonian script approach. The most famous treaty on horses, that of Kikkuli di Mitanni, is written in Hittite and was found in ḫattuša, but medium-healthy texts were also found in Assur and Ugaritic texts. [81]

Texts dedicated to the manufacture of vitrea pasta come from the Babylon of Gulkishar’s times, the sixth sovereign of the town of the sea. With magical provisions are fragment effective indications for the production of the Makkah : a vitrea pasta was obtained in modern times, following the indications of those texts. [81]

Finally, there are texts on the manufacture of perfumes and on the production of spices, always from medium-health environments. [81]

The enslavement for peasants’ debts [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

Connected to the rise of a “military aristocracy”, with its heroic ideals and its land properties, it is another typical trend of the late bronze: already in the texts of Mari, but then above all in those of Khana and Alalakh VII, they begin to appear clauses that make the effects of a liberation edict on certain asserted subjects null. From the end of the seventeenth century they are no longer emanated edicts of remission of the debts. Compared to the paleo-babylonian age, the late bronze is a more ruthless era. The peasant masses are now no longer central to carrying out the war and remain even more isolated in the light of the convergence of the interests of king and maryannu . The members of the Palatine and military elite are then the same money loans, so they have no interest in providing for social correctors who favor a distribution rebalancing. From a propaganda point of view, the strong and courageous king replaces the right king. [85]

Main kingdoms of the late bronze [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

Also called “the era of great kingdoms”, this period sees precisely the development of superpowers that will decide the fate of history: Egypt, Hatti (Ittiti), Mitanni, Babylon Cassita and Assyria.

These states came to be created not for migratory movements, but because of the voids of power that the old dominators had left (e.g. Yamhad; Mitanni or Babylon; Casiti) or with the aggregation of independent cities in a single state (e.g. Hatti).

The Hurriti lived in northern Mesopotamia and in the immediate vicinity of East and west, approximately around 2500 BC. They probably originated from the Caucasus and went from the north, but this is not given with certainty. Their homeland was Subartu, the Khabur river valley. Subsequently they established themselves as dominators of small kingdoms in northern Mesopotamia and Syria. The largest and most influential Hurrite nation was the Kingdom of Mitanni. The Hurriti played a substantial role in the history of the Hittites.

Ishuwa (or Išuwa) was an ancient kingdom in Anatolia. The name is attested for the first time in the second millennium BC. In the classic period its territory corresponded more or less to the current Armenia. The first agricultural revolution had one of the places of development in Ishuwa. Urban centers concentrated along the Valle dell’Uufrate around 3500 BC, while the first states followed in the third millennium BC. The name “Ishuwa” is not known except starting from the documentation of the second millennium BC. Few literary sources have been discovered in his regard and the primary sources are extracted from heritage texts. To the west of Ishuwa the nearby Kingdom of the Hittites extended, a mountain and combative people. It is said that King Hittite Hattušili I (1600 BC) had marched with his army through the Euphrates, destroying the cities of the place. The confirmation comes from the confirmation, that is, from the burnt layers discovered in the city sites in Ishuwa, dated pressure at the same time. After the end of the Hittite Empire at the beginning of the twelfth century BC A new state emerged in the kingdom of Ishuwa. The city of Malatya became the center of one of the so-called neo-hygiti kingdoms. The movement of the nomadic people could have weakened the Kingdom of Malatya before the axira final invasion. The decline of settlements and culture in IShuwa from the seventh century BC Until the Roman period it was probably caused by this shift of people. The Armenians subsequently settled in the area, being natives of the Armenian plateau, relating to the oldest inhabitants of Ishuwa.

Kizzuwatna is the name of an ancient kingdom of the second millennium BC. Located on the plateaus of south-eastern Anatolia, close to the Gulf of İSkenderun, currently in Turkey, surrounded the Tauro mountain range and the Ceyhan river [eighty six] . The center of the kingdom was the city of Kummanni, located in the plateau. In a subsequent period, the same region was known as Cilicia.

Luvio is an extinct ancient language of the Anatolica branch of the Indo -European languages family. The Luvi speakers gradually expanded through Anatolia, contributing to the fall, after 1180 BC. About, of the Hittite Empire, where this language was already talking about. Luvio was also the language spoken in the neo-Ityyy States of Syria, such as Melid and Karkemiš, as well as in the central kingdom of Tabal who flourished around 900 BC. Luvio preserved in two forms, defined according to the writing system used to represent them: Luvio Cuneiformo and Luvio Gioroglifico.

Mitanni was a Hurrite kingdom located in northern Mesopotamia (1500 BC ca.). The culmination of its power was had during the 14th century BC: then embraced what today is south-eastern Turkey, northern Syria and northern Iraq (correspondent pressed to the Kurdistan region), and was focused on the capital Washukanni, whose precise location has not yet been determined by archaeologists. It is thought that Mitanni was a “feudal” state, led by the warrior nobility of Indo-Arian descent, which invaded the region of the Levant at a certain point during the seventeenth century BC. The diffusion in Syria of a type of characteristic ceramic associated with the culture of Kura-Araxes has been connected with this movement, although its dating is perhaps too archaic. [eighty seven]

The Aramei were a Semitic people (western Semitic linguistic group), semi-nomadic and pastoral that lived in the upper Mesopotamia and Aram. The Aramei never had a unified empire: they were divided into independent kingdoms, all located in the Near East. Also for the Aramei, the privilege of imposing their language and culture to the entire East and beyond, favored in part by the mass transfers decreed by the subsequent empires, including those of the Assyrians and the Babylonians are realized. Scholars also used the term “Aramaicization” for the languages and cultures of the Assyrian-Babylonian peoples, who ended up adopting Aramaic as a Franca language.

“Popoli del Mare” is a definition used for a confederation of predons of the sea of the second millennium BC, who, sailing along the eastern coasts of the Mediterranean, caused many political concerns: they attempted to control the Egyptian territory during the late period of the XIX Dynasty, especially during eight years of the Ramese III Kingdom of the XX Dynasty. [88] The Egyptian Pharaoh Merenptah explicitly refers to them with the term “nations (or peoples) foreigners [89] of the sea ” [90] [91] In his great registration of Karnak. [92]

The “collapse of the Bronze Age” is the definition given by those historians who see the transition from the late Bronze Age to the first phase of the Iron Age as violent, sudden and culturally destructive, expressed by the collapse of the Aegean palatial societies and Anatolia, replaced after an interruption from the cultures of isolated villages of dark ages. The collapse of the Bronze Age can be seen in the context of a technological history that saw the slow, relatively continuous expansion of the technology of steelurgery in the region, which began early in the XIII and XII centuries in what is currently Romania. [93] The cultural collapse of the Mycenaean Kingdoms, of the Hittite Empire in Anatolia and Syria, and the Egyptian Empire in Syria and Palestine, the splitting of long -distance commercial contacts and the sudden eclipse of literacy, happened between 1206 and 1150 B.C. In the first phase of this period, almost every city between Troy and Gaza was violently destroyed, and often left empty (for example, ḫttuša, Mycenae, Ugarit). The gradual end of the “Buia Age” that follows the rise of the stable new Aramean kingdoms in the mid-tenth century BC, and the advent of the newlyssly infant Empire.

The iron age of the Near East goes from 1200 to 500 BC [ten]

During the first phase of the Iron Age, Axiria took on a position of great regional power (although only after the reforms of Tiglatpiler III, in the eighth century BC), competing with Babylon and other minor powers for the domain of the region [ninety four] . In the middle period of the late bronze age, Assyria was a minor kingdom of northern Mesopotamia (current northern Iraq), competing for dominance with the Babylon rival of southern Mesopotamia. Starting with the AdaD-Nirari II campaign, it became a great regional power, growing in such a way as to become a serious threat to the XXV Dynasty of Egypt. The neo-axus Empire succeeded that of the Middle Assiro (XIV-X century BC). Some scholars, such as Richard Nelson Frye, consider the neo-absir empire as the first true empire in the history of humanity. [95] During this period, Aramaic was established as the official language of the Empire, alongside the ACCICA language. [95]

The states of the neo-Eittite kingdom were political entities that spoke Luvio, Aramaic and Phoenician of northern Syria and southern Anatolia in the Iron Age, which arose following the collapse of the Hittite Empire around 1180 BC, and lasted pressure up to 700 BC The term “neo-itita” is sometimes specifically reserved for principalities who spoke Luvio as Melid (Malatya) and Karkemiš, although in a broader sense the most extensive cultural term is “siro-itey” for all the entities that arose in central-southern Anatolia following the hip collapse-as tabal and Quwê – or those of northern and coastal Syria [96] [97] .

Urartu was an ancient reign of Armenia and northern Mesopotamia [98] , existed more or less from 860 BC, emerging from the late Bronze Age, until 585 BC. The Kingdom of Urartu was located in the mountainous plateau between Asia Minor, Mesopotamia and the Caucasus chain, subsequently known as the Armenian plateau, focusing around Lake Van (currently part of the Eastern Turkey). The name corresponds to the biblical Ararat .

The term neo-babylonian empire refers to Babylon Under the government of the XI Dynasty (“Caldea”), from the rebellion of Nabopolassar in 626 BC. Until the invasion of Cyrus II of Persia in 539 BC, in particular including the reign of Nabukodon Moral II. Through centuries of Assyira domination, Babylon enjoyed a remarkable social status, trying several times to rebel against the yoke of the dominators. However, the Assyrians always managed in one way or another to restore the loyalty of Babylon to the Empire, through concessions of growing privileges, or militarily. Finally in 627 BC With the death of the last Powerful Assyrian reigning, Sardanapalo, Babylon rebelled under Nabopolassar the Caldeo the following year. With the help of the Middle, Ninive was sacked in 612 BC, and the seat of the power of the Empire was moved to Babylon again.

The Achemenide Empire was the first of the Persian empires to govern on significant areas of the great Iran, and the second large Iranian empire (after the Empire of the Middle). At the height of its power, with a vast extension of approximately 7.5 million km², the Achaemenid Empire was territorially the wider than classical antiquity. It extended to three continents, including the territories of the current Afghanistan, part of Pakistan, Central Asia, Asia Minor, Tracia, many coastal regions of the Black Sea, Iraq, Northern Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Israel, Lebanon, Syria and all Inhabited centers of ancient Egypt to Libya. The Empire is mentioned in history as the enemy of the Greek State Cities in the Greek-Persian wars, as a liberator of the Israelites from their Babylonian captivity, and for having established Aramaic as the official language of the empire.

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 15.

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 108.

- ^ Liverani, The ancient Near East , intervention at the Modena conference The story is of all. New horizons and good practices in teaching history (5-10 September 2005).

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 10.

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 5.

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 6.

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 13.

- ^ Van de Miieroop, p. 5 .

- ^ a b Van de Miieroop, p. 3 .

- ^ a b c d It is Liverani 2009, p. 24.

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 17.

- ^ a b c Vacca-d’andrea, p. 31 .

- ^ Van de Mieroop, pp. 17-18 .

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 23.

- ^ Liverani 2009, pp. 23-25 .

- ^ a b Liverani 2009, p. 25.

- ^ Liverani 2009, pp. 25-6 .

- ^ a b Chen, pp. 1-2 .

- ^ a b Van de Miieroop, p. 5 .

- ^ a b c Liverani 2009, p. 64.

- ^ Liverani 2009, pp. 64-5 .

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 63.

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 64.

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 66.

- ^ a b Liverani 2009, p. 69.

- ^ Liverani 2009, pp. 80-1 .

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 74.

- ^ Liverani 2009, pp. 72-3 .

- ^ a b Liverani 2009, p. 72.

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 71.

- ^ a b Liverani 2009, pp. 78-9 .

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 81.

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 84.

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. ninety two . The dates indicated rely on the average chronology.

- ^ Liverani 2009, pp. 90-5 .

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 147 . The dates indicated rely on the average chronology.

- ^ Liverani 2009, pp. 114-115 .

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 128.

- ^ a b Liverani 2009, p. 201.

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 166.

- ^ a b c Liverani 2009, p. 148.

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 150.

- ^ a b c d It is f Liverani 2009, p. 227.

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 157.

- ^ Liverani 2009, pp. 157, 159.

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 164.

- ^ According to the average chronology (cf. Liverani 2009, p. 164 ). The period is also indicated as “ancient dynastic”, in the abbreviation “from”: the abbreviations from I, from II, from IIIA, from IIIB (cf. Bears 2011, p. 22 ).

- ^ Liverani 2009, pp. 201-202 .

- ^ a b Liverani 2009, p. 202.

- ^ Bears 2011, p. 11. [first]

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 204.

- ^ Liverani 2009, pp. 204-205 .

- ^ Liverani 2009, pp. 205-6 .

- ^ Liverani 2009, pp. 206-207 .

- ^ Liverden are francesci, Daviri and Martino, Battini Inter 2002.

- ^ a b c Liverani 2009, p. 228.

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 229.

- ^ Liverani 2009, pp. 229-230 .

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 230.

- ^ Liverani 2009, pp. 230-231 .

- ^ Card on the Accadi , in treccani.it.

- ^ Caselli and Fina 1999, p. 10.

- ^ Semite card , in treccani.it.

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 235.

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 236.

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 263.

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 267 .

- ^ ( IN ) Claudia E. Suter, Gudea’s Temple Building: The Representation of an Early Mesopotamian Ruler in Text and Image , Groningen, STYX Publications, 2000, p. 17.

- ^ Beaulieu, p. 51 .

- ^ The dates are those indicated by Liverani 2009, p. 235 .

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 265 .

- ^ Form are Britishmuseum.org.

- ^ a b c Van de Miieroop, p. 92 .

- ^ Van de Miieroop, p. 90 .

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 317 .

- ^ Liverani 2009, p. 318 .

- ^ Liverani 2009, pp. 322-324 .

- ^ Liverani, Ancient east. History Economy Company .

- ^ Liverani 2009, pp. 449-450 .

- ^ Liverani 2009, pp. 453 and 462.

- ^ a b c d Liverani 2009, p. 461.

- ^ a b c Liverani 2009, pp. 451-453 .

- ^ a b c Liverani 2009, pp. 453-457 .

- ^ a b Liverani 2009, pp. 458-461 .

- ^ Liverani 2009, pp. 457-458 .

- ^ Traditionally known also as Pyramos or Pyramus (from Greek Pylon ) o Leucosyrus.

- ^ Mallory e Adams 1997.

- ^ An appropriate table of peoples of the sea in hieroglyphics, transliteration and English translation is offered by the dissertation of Woodhuizen, 2006, who developed it from the works of Kitchen there.

- ^ As noted by Gardiner ( Gardiner 1947, p. 196 ), other texts have ḫȝty.w “Peoples-Strenieri”; Both terms can well refer to the concept of “foreigners”. Zangger, expressing a widespread point of view, states that the term “peoples of the sea” does not translate this and other expressions, but it is an academic innovation. The dissertation of Woudhuizen and Morris’ essay indicate in Gaston Maspero the first who used the term “Peuples de la Mer”, in 1881.

- ^ Gardiner 1947, p. 196.

- ^ Mana 2003, tel. 55.

- ^ Towards 52. Registration is shown in Mana 2003, p. 55, Tav. 12.

- ^ See A. Stoia and other essays in Sørensen 1989 It is Wertime e Muhly 1980 .

- ^ Tadmor 1994, p. 29.

- ^ a b Frye 1992

«And the Assyrian Empire, was the first true empire in history. What I want to mean, is that it had many different people included in the empire, all speaking Aramaic, becoming what they could be called, “Assyrian citizens”. It was the first period of the story in which this happens. For example, the musicians elamit, were brought to nineive, it is axious facts’; This means that Assyria was more than a small region: it was an empire, the entire fertile crescent. ”

- ^ Hawkins 1982, pp. 372-441 .

- ^ Hawkins 1995, pp. 87-101 .

- ^ ( IN ) Urartu . are The Free Dictionary , The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia, 2013. URL consulted on January 30, 2014 .

- ( IN ) Paul-Alain Beaulieu, A History of Babylon, 2200 BC – AD 75 , John Wiley & Sons, 2018.

- Giovanni Caselli and Giuseppe M. della Fina, The great civilizations of the ancient world , Florence, Giunti Editore, 1999. URL consulted on January 30, 2014 .

- ( IN ) Fei Chen, Study on the Synchronistic King List from Ashur , Brill, 2020.

- ( IN ) Richard Nelson Frye, Assyria and Syria: Synonyms , in Journal of Near Eastern Studies , 1992.

- ( IN ) Alan H. Gardiner, Ancient Egyptian Onomastica , I, Oxford University, 1947.

- ( IN ) William W. Hallo & William Kelly Simpson, The Ancient Near East. A History , Holt Rinehart and Winston Editori, 1997

- ( IN ) John David Hawkins, Neo-Hittite States in Syria and Anatolia , in Cambridge Ancient History , vol. 3.1, 2ª ed., Cambridge University Press, 1982, ISBN 978-0-521-22496-3.

- ( IN ) John David Hawkins, The Political Geography of North Syria and South-East Anatolia in the Neo-Assyrian Period , in Mario Liverani (edited by), Neo -Assyrian Geography – University of Rome “La Sapienza,” Department of historical, archaeological and anthropological sciences of antiquity, notebooks of historical geography , vol. 5, Roma, Sargon srl, 1995.

- Mario Liverani, Antico East: History, Society, Economy , Rome-Bari, Laterza, 2009, ISBN 978-88-420-9041-0.

- Mario Liveravani, Marcellanca Rasci Per Martino and Laura Battinini, Paola Battains, From the first settlements to the urban phenomenon. Near East and Egypt , in The world of archeology – Italian Encyclopedia Treccani.it , 2002. URL consulted on January 30, 2014 .

- ( IN ) James P. Mallory, Kuro-Araxes Culture , in Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture , Londra, Fitzroy Dearborn, 1997, ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5.

- ( IN ) Colleen in mana, The Great Karnak Inscription of Merneptah: Grand Strategy in the 13th Century BC , New Haven, Yale Egyptological Seminar, 2003, ISBN 978-0-9740025-0-7.

- Valentina Orsi, Crisis and regeneration in the Upper Khabur valley (Syria): ceramic production in the transition from ancient bronze to medium bronze , flight. 1, FIENCES, Institivity Press, 2011, 2011, ISBN 978-888-6555-08-7. URL consulted on January 30, 2014 .

- Karen Radner, Nadine Moeller and D. T. Potts (edited by), Volume 1: From the Beginnings to Old Kingdom Egypt and the Dynasty of Akkad , in The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East , New York, Oxford University Press, 2020.

- Karen Radner, Nadine Moeller and D. T. Potts (edited by), Volume 2: From the End of the Third Millennium BC to the Fall of Babylon , in The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East , New York, Oxford University Press, 2022.

- Karen Radner, Nadine Moeller and D. T. Potts (edited by), Volume 3: From the Hyksos to the Late Second Millennium BC , in The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East , New York, Oxford University Press, 2022.

- ( IN ) Jack Sasson (ed.), Civilizations of the Ancient Near East , New York, 1995

- ( IN ) Marie Louise Stig Sørensen, The Bronze Age – Iron Age Transition in Europe: Aspects of Continuity and Change in European Societies c. 1200-500 BC , in British Archaeological Reports, International Series 483 , Oxford, Archaeopress, 1989.

- ( IN ) Hayim Tadmor, The Inscriptions of Tiglath-pileser III, King of Assyria , Jerusalem, The Israel Academy of Sciences and Humanities, 1994.

- Agnese Vacca and Marta D’Andrea, Chronology of ancient Mesopotamia , in Davide Nadali and Andrea Polcaro (edited by), Archeology of Antica Mesopotamia , Rome, Carocci, 2015, pp. 29-45, ISBN 978-88-430-7783-0. Hosted on academia.edu.

- ( IN ) Marc van de Mieroop, A History of the Ancient Near East , 3ª ed., Malden, Wiley Blackwell, 2016, ISBN 978-1-118-71816-2.

- ( IN ) T.A. Wertime e J.D. Muhly, The Coming of the Age of Iron , New Haven and London, Yale University Press, 1980.

Recent Comments