Jan Borreman – Wikipédia

For the homonymous article, see Borreman.

|

Jan Borreman the old, too Jan Borman or Borremans (Active in Brussels from 1479 to 1520), is the best wooden sculptor ( «Best Beltsvæder» ) of his time in Brussels. His late Gothic style works not only found a market in the ancient Netherlands, but also, passing through the merchant roads of the time, to the north of the Holy Roman Empire and to the Scandinavian countries.

1479: Bourgeoisie right in Brussels [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

In 1479, Borreman acquired the right of bourgeoisie of the city of Brussels and became a member of the Guild of Brick , who united stone tailors, masons, sculptors and slate workers.

1507 – 1510: Cooperation with Jan Petercels [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

The organization of work in the Brussels guild [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

The superior quality of Brussels altarpieces, and in particular those of the members of the Borreman dynasty, contrasts with the production in series of Antwerp sculptors. The cause was undoubtedly, in part, the differences in the organization of work between the Guilds of Antwerp and those of Brussels. If the Antwerp sculptors produced for a free market, those of Brussels worked rather on order. In the two cities, various specialists (carpenters, painters and sculptors) collaborated on these altarpieces, since dispersed across Europe. In Brussels, however, there was a greater variation in the form and in the themes processed because of the many commands of customers each with its wishes and requirements, but also because of the orders placed by painters themselves providing the drawings. However, in Antwerp, the crates of the altarpieces were still built according to the same schemes. It was a real serial work. The themes were most often limited to the most popular subjects, worthy of any Church: the passion and the life of Mary [ first ] .

1507: Borreman uses Petercels [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

A better understanding of the subcontracting system of Brussels guilds is obtained by the letter that the brewers of Louvain addressed to Jan Borreman in 1507, asking him to design the central ball of their altarpiece, dedicated to Saint Arnoul, in a different way Compared to the baldaquins of the side panels; That is to say in a fairly daring style for this time, which is close to that applied by the painter Jean Gossaert and quickly imitated everywhere. The designer-sculptor, nodding at the request, immediately sought a detailed and refined masonry sculptor quite skilful for him to execute the most meticulous work: he found him in Jan Petercels, who was inspired by the drawings of Matthieu Keldermans, member of the renowned family of architects and Malinois sculptors [ 2 ] .

1510: In Turnhout, Petercels is asked to cooperate with Borreman [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

Cooperation with Petercels was again documented in 1510, the year when the brotherhood of the Saint-Sacrament of Turnhout charged Petercels to make a altarpiece on the theme of the last period. Petercels featured entrepreneur. Exceptionally, the brotherhood demanded from him to entrust the sculptural part in subcontracting to Jan Borreman or to the son of his, Passchier.

That a client posed such a condition to a sculptor of Turnhout, Louvain or Antwerp, a city nearby and export port of choice for altarpieces at the time, can not mean something other than Turnhout, we wanted to ambitiously and at all costs obtain the collaboration of the famous Brussels Master. Apparently, they considered Borreman as the best of wood sculptors. The contract explicitly stipulates that the characters would be sculpted by Jan Borreman or Passchier, his son [ 3 ] . Under the contract, Borreman had to execute the characters in an exquisite and perfect way ( “Zundlinge and Reyn” ) And we also wanted the gilder to applied polychromy the next day or on the next day ( «Morning Often Tomorrow» ). In the same spirit, it imposed on Petercels to add two side panels to the table, refined and sufficiently solid: «Item, the es oick voirwerde that this table sal with dice do notesle, permanent werck and Sterck, to have it scited with potoratures in the event of standing.” [ 3 ] . After the altarpiece completion, Petercels would have received 100 guilders.

In any case, it was an responsibility for a jury to judge the quality of the altarpiece [ 4 ] . In the event that the quality is questioned, the fees collected by Petercel are reduced. Apparently, the control of a high quality and initially non -polychrome wood altarpiece involved the prior intention of the principal to have it brown later. Can there be a relationship with possible budgetary restrictions when the order is placed? In all likelihood, money for a predelle was missing: «Item, the es oick vorwerde that Master Jan does the foot sal sal ” [ 4 ] . We undoubtedly accepted the delivery of a altarpiece of incoherent and manifestly unfinished aspect. The sources remain silent when it comes to knowing when and if the brotherhood put an end to this situation by sending the altarpiece to the gilder so that it applied a polychrome layer.

1513: Ducal accounting praises Borreman [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

The receipt of 1513 in the Ducaux accounts for the statues crowning the fence of Place des Bailles, in front of the Palais du Coudenberg in Brussels, tells us that Jan Borreman was once considered the best of wooden sculptors [ 5 ] . This grid, made up of a balustrade decorated with statues, which we still know thanks to ancient engravings, inspired the architect Henri Beyaert (1823-1894) by his shape and by his style, when he converts, to the square of Petit-Sablon, the space around the sculptural group representing the counts of Egmont and Hornes in a commemorative monument for humanism and reform in the Netherlands in XVI It is century. This square was solemnly inaugurated in 1890 [ 6 ] .

Rétable de Saint Georges de la Chapelle de Notre-Dame de Ginderbuyten in Louvain [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

The altarpiece of Saint Georges de Borreman is considered to be his masterpiece. Well documented in the archives, the work has become that of reference for new attributions. The oak altar, «The Tablement of Sint-Jooris [ 7 ] » , was commissioned by the Crossbow Guild, called the Sixty , the sixty, for their chapel of Notre-Dame-Hors-les-Murs ( «In Ons-Lieve Vrouwe Capelle Ginderbuyten» ), located in the Hullstraete , currently rue de Tirlemont, in Louvain. Historical documents not only confirm the paternity of Master Jean Borreman of Brussels, who had designed it with a double pair of shutters, but also recognize that the work was sculpted in good wood, whose quality had been controlled, and that The altarpiece was indeed done according to the model [ 8 ] , [ 9 ] . The chapel of Notre-Dame-Hors-les-Murs having been demolished at the end of XVIII It is century [ ten ] , the altarpiece is currently at the royal museums of art and history of Belgium. Formerly, these altarpieces cost a fortune. It is estimated that a altarpiece was worth as much as a cog of 250 tons. The altarpieces were even pledged for the cargo of a ship.

On the edge of the dress of one of the figures, Borreman has signed Jan His altarpiece. In addition, the altarpiece is provided with guarantee punches of the city of Brussels and the date in Roman numerals MCCCCXCIII (1493). At that time, a signature was a fairly new phenomenon, a sign of an awareness of craftsmen. Perhaps Borreman wanted to express that he realized his artist qualities. The mention of the author’s name was probably also a commercial strategy: for the buyer, the name guaranteed the quality of the product. As the production of anonymous mass of works of art had taken a considerable boom at that time, among others in Antwerp, it was also a means of increasing the fame of craftsmen.

The altarpiece of Saint Georges is considered to be a masterpiece [ ten ] From the flamboyant late medieval sculpture because of its plasticity, the work probably never having been polychromy, and because of the treatment of the legends and the complex gestures of the many characters, arranged in small compartments. That the altarpiece has never received a polychrome layer is undoubtedly, although indirectly, to relate to the organization of subcontracting work, as of use to the Brussels guilds. Acceptance of an order was reserved for wooden sculptors and painters, the latter being treated on an equal footing when it was the execution of orders. Regarding the sale on the market, only painters were allowed to sell completed altarpieces, sculptors only having this right for non -polychrome works. The painters were therefore in a privileged position, while the sculptors depended, to a large extent, on the initiative of painters or orders placed to painters. There has been no trace of polychromy on this altarpiece, which would imply either that polychromy has been removed in a later time and for unknown reasons, or that the altarpiece has never reached the painter and that the wooden sculptor presented it without polychromy to the principal. Perhaps a dispute was the cause [ 11 ] .

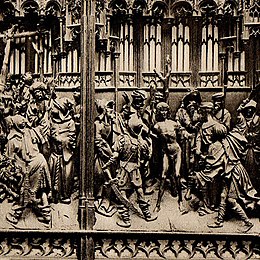

The altarpiece measures 163.5 x 284.5 x 30.5 cm and represents the different tortures suffered by Saint Georges, as well as its ultimate decapitation; Besides this last scene, Alexandra, the wife of Proconsul Dacien, converted to the Roman religion after having attended the agony of the martyr, was also beheaded (his head, having been stolen from the museum, had been replaced, but reappeared later). With each scene, Dacien rubs shoulders with the Diocletian emperor in the name of which these tortures were executed. The proconsul has a pointed face, carries a forked beard and earrings, and is wearing a flat cap. The emperor is wrapped in a coat to the Hermine pass; He is wearing a hat surrounded by a crown and he wears a braided beard [ twelfth ] .

The receipt of 1493 proves that at the origin, the altarpiece had been provided with a double pair of shutters; This is confirmed by the hinges in the shape of hinges on the amounts of existing shutters. It is uncertain if the shutters were painted panels; It frequently happened that they were not added until later or even never [ 13 ] .

Sacred legends depicting macabre paintings were pious subjects supposed to encourage the faithful (mostly illiterate) to devotion. Borreman sculpta with as much unusual realism as bravery. The rupture of style that Borreman reaches by this altarpiece lies in the spatial and concentric arrangement of figures around a main character. The Renaissance undoubtedly entered the paintings of this altarpiece, whose architectural elements are still late Gothic style [ twelfth ] . The few characters, seen from back to foreground, and the pronounced individualization of the figures are all new elements [ 14 ] .

During the XIX It is century, a restoration of the altarpiece left it with an inverted presentation of the stages of the martyrdom of Saint-Georges [ ten ] . Royal Museums of Art and History (MRAH) also had it restored at the start of XXI It is century and restored the original order of decapitation, which had been done when the altarpiece was created [ ten ] .

Tomb of Marie de Bourgogne [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

The late Gothic style tomb of the Duchess Marie de Bourgogne, heiress of Burgundy and wife of Maximilien I is From Austria, currently located in the choir of the Notre-Dame de Bruges church, was produced around 1495-1502. It is the fruit of collaboration between different craftsmen: the wooden model was created by Jan Borreman, while the Brussels Dinandier, Renier Van Thienen, flowed in copper this recumbent [ 15 ] . Marie de Bourgogne, born in Brussels the , had succumbed, in Bruges the , in the aftermath of an equestrian accident in the woods of Torhout. The funeral statue had been ordered to the sculptor Jan Borreman, in Brussels, by the Maximilien Archduke I is . Borreman had developed his wooden model from the mortuary mask of the deceased duchess. According to the use of the Habsbourg dynasty, the urn containing the heart of Marie’s son, Duke Philippe le Beau, was deposited in 1507, a year after his death.

The funeral monument is a masterpiece of courteous naturalism, especially by the facial expression of recumbent , the elongated figure. The Duchess is represented in a particularly tangible and natural way. The crowned head sinks into a pulp with pompoms. On the chest, the hands are in a prayer position. The body is wrapped in a dress with heavy folds, but majestic and flexible, and large sleeves, resting next to a folded cape at the edge and richly ornament. The lying rests on a rectangular and solid sarcophagus, a bluish or blackish, finely polished slate base. Below is the base, lined with a plinth of the same material. The two side sides of the sarcophagus are decorated with genealogical trees, made of copper, whose flexible symmetry of the deployed branches surrounds ECUs in ordered enamel, held by angels. The short sides respectively carry the individual titles and emblems of the duchess, while the exclusively religious element is limited to the figures of the four evangelists in medieval costume which, like figures released under their small balls, adorn the ribs. Different counties and duchies of the seventeen provinces [ 16 ] , the multicolored crowns on banners are arranged in a hollow profile of the cover, around the duchess [ 17 ] . At the foot of the statue of Marie lengthen two German bassine, symbols of loyalty to the spouse and the father. Under the French occupation, the recumbers were removed and the grave became the target of the securities of burials.

Triumphal cross of the Saint-Pierre church in Louvain [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

The triumphant oak cross of the Saint-Pierre collegiate church in Louvain, composed of life-size statues of the crucified Christ, the Virgin Mary and John the Evangelist who retain traces of the original polychromy, is attributed to Jan Borreman. A small altar is suspended at the foot of the cross. Borreman was also said to have been associated with the execution of the roodle of this same church.

Works attributed to the members of the Borreman dynasty [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

In addition to the aforementioned works, the first two of which are certain attributions, the third being attempt, a number of anonymous works have been awarded to Borreman or his family members.

Based on the similarity between the funeral monument of Marie de Bourgogne of the Notre-Dame de Bruges church and the Madeleine of around 1490 of the collections of the royal museums of art and history of Belgium, Count Joseph de Borchgrave ‘Altena attributed the last to the sculptor Jan Borreman. We have also observed a resemblance between this figurine and the lady of honor of Alexandra of the altarpiece of Saint-Georges at the royal museums of art and history of Belgium, which testifies to grace and charm such. The punch of the Brussels guild, the wooden hammer, appears under the statuette, thus confirming the attribution [ 18 ] .

The attribution by Friedrich Schlie of the Antwerp altarpiece, dating from 1518, of the Sainte-Marie church of Lübeck confirmed a previous attribution by Adolph Goldschmidt, made in 1889 [ 19 ] , which went in the same direction.

In 1933, Johnny Roosval recognized the fatherhood of Jan Borreman for a number of altarpieces in Sweden: in Villberga, at the Vaddstena monastery, in Västerås (the altarpiece of passion, known as Västerås III ) It Dans La Cathsdraldal Drawn the vulnerable [ 20 ] .

The capital work of the alleged son of Jan Borreman, Jan Borreman the Younger, and his collaborators, is the altar of the passion of 1522 of the Sainte-Marie church in Güstrow (Pfarrkrche St. Marien), whose painted panels have sometimes been attributed to Bernard Van Orley, sometimes to the master of the altar of Güstrow [ 21 ] . This altar carries the signature of Jan Borman On the sheath of a soldier to the right of the crucifixion. In addition, under the Caisse du Vrai, is the hallmark of the city of Brussels. Jan Borman the young was already active around 1499, the year he was listed as a member of the guild.

The third of the members of the Borreman family known by historical documents is Passchier Borreman, still active in 1537. He was probably a brother of Jan the young and a son of Jan the old. He became master of the guild in 1491. We know of him the altarpiece of Saint Crépin and Saint Crépinien, dated around 1520, of the Sainte-Waudru church of Herentals; He sculpted his name in two figures of the altarpiece. Other attributions to this wood sculptor are still a subject of discussion. The herental altarpiece – undoubtedly an order, undoubtedly made by a guild – was dedicated to the life of the holy patterns of the Tanneurs and Sabotiers Guilders [ 22 ] .

Selective list of works [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

- Wooden model for the recuperation of the funerary monument of Marie de Bourgogne, Notre-Dame church, Bruges

- Vétable de Saint Georges, coming from the Notre-Dame-Hors-les-Murs church ( Onze-Lieve-Vrouw van Ginderbuyten ), Louvain, currently at the royal museums of art and history of Brussels [ ten ]

- Triomphale cross, Saint-Pierre church, Louvain (around 1500, attribution, restored in 1996-1998)

- Marie-Madeleine, around 1490 (attribution), royal museums of art and history of Brussels

- Grid of Place des Bailles in front of the Palais du Coudenberg in Brussels (missing)

- Activate of the Borreman family workshop at the Schnütgen museum in Cologne [ 23 ]

- Ghislaine Derveaux-van Ussel. Hans Nieuwdorp et J. Steppe, «Retabels» , Public art ownership in Flanders , 1979, p. 16 , 20

- The Art Bulletin , Juin 2000, Etan Matt Cavals

- Edward VAN EVEN. “The author of the 1493 altarpiece of the Hal Porte Museum in Brussels” , Bulletin of royal commissions of art and archeology 16, 1877, p. 588 : «Item, the es oick vorwerde that the persona caught, by Jannen Borman oft Paesshier, Synen Sone, in Brussels weighing, Zundlinge and Reyn, with Aenmercken that man tomorrow oft are stoefferen. ”

- Edward VAN EVEN. “The author of the 1493 altarpiece of the Hal Porte Museum in Brussels” , Bulletin of royal commissions of art and archeology 16 , 1877, p. 589 , «Item, the es oick vorwerden that so much when that yards are pleased, that sal standing from masters of Kynesse and in that it is one that the Werck also does not and es have been pleased, nair the gel that they corten sals are told. ”

- Cor Engelen. Salt lion , Jan Mertens and De Laatgotiek, confrontation with Jan Borreman: Essay for insight and overview of the Late Gothic , Kessel-Lo, 1993, p. 262 , «That he is the best master scare es» .

- Gérard des MAREZ. Illustrated Guide of Brussels , First part, civil monuments, Belgian Touring Club, 1917, p. 172

- The painting of Saint Georges

- Ghislaine Derveaux-Van Ussel. Wooden retable , Museum guide , Royal Museums of Art and History of Belgium, Brussels, 1977, p. 11

- Edward VAN EVEN. “The author of the 1493 altarpiece of the Hal Porte Museum in Brussels” , Bulletin of royal commissions of art and archeology 16 , 1877, p. 586 , «Macked by Master Jan Borreman, to Brussels, with dice doors, cut uyt well -approved woode, according to the model daeraf Wesende» .

- Culture of France Télévisions writing, ‘ A 15th century altarpiece, masterpiece of the Middle Ages, finds its Brussels museum after its restoration » , on Franceinfo , (consulted the )

- E. Vandamme (1985) and Br. D’Hainaut-Zveny (1987), p. 11

- Ghislaine Derveaux-Van Ussel. Wooden retable , Museumgids , Royal Museums of Art and History , Brussels, 1977, p. ten -11.

- Ghislaine Derveaux-Van Ussel. Wooden retable , Museumgids , Royal Museums of Art and History , Brussels, 1977, p. 11 .

- Ghislaine Derveaux-van Ussel, Hans Nieuwdorp et J. Steppe. Retabels in public art ownership in Flanders , 1979, p. 19

- André A. Moerman. «Praal grave of Maria van Burgundy, Jan Borman and Reinier Jansz. van Thienen » , Public art ownership , 1964, p. 27A

- The Burgundian territories of the former Netherlands on which Marie had made her authority prevail

- André A. Moerman. «Praal grave of Maria van Burgundy, Jan Borman and Reinier Jansz. van Thienen » , Public art ownership , 1964, p. 27b

- Ad. Jansen. H. Maria-Magdalena, Jan Borman , In : Public art ownership , 1965, 5a-b

- GOLDSCHMIDT S. 23 f.

- ROSSVAL S. 16 (20 ff.)

- CATHELINE Réier-decents (you.). The altarpiece of the passion of the Sainte-Marie church in Gustrow. Historical and technological study , Brussels, 2014; Sacha Zdanov. “New perspectives on the design of the painted shutters of mixed brabaning altarpieces: Güstrow’s altarpiece”, Annals of art history and archeology of the Free University of Brussels 39, 2017, p. 103-121 [first]

- Ghislaine Derveaux-van Ussel, Hans Nieuwdorp, Et J. Steppe. Retabels in public art ownership in Flanders , 1979, p. 40

- Fig: Brussels altar in the Museum Schnütgen in Cologne

Bibliography [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

- (fr) Borchgrave d’alena, Comte Joseph de. The altarpiece of Saint Georges de Jan Borman , Brussels, Dupriez, 1947.

- (nl) Borchgrave d’alena, Comte Joseph de. The St-Joris retable of Jan Borman , Anvers, Standard bookstore, 1947 .

- (nl) Borchgrave d’alena, Comte Joseph de. Museums of Belgium , National Archeology, Arts and Crafts, Folklore, Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels, Part 3, 1958 No. 45 .

- (in) Debane, Marjan (you.), Levey, michel ( et al. ). Borman, a Family of Northern Renaissance Sculptors , 2019, exhibition catalog Borman and son (M-Museum, Louvain, Belgium) .

- (nl) Duverger, Jean. “The masters of the burial monument of Maria van Bourgondia in Bruges” , Yearbook of the Royal Flemish Academy of Belgium, VIII , 1946.

- (nl) Engelen, Cor. Zoutleeuw, Jan Mertens and De Laatgotiek, confrontation with Jan Borreman: Essay for insight and overview of the Late Gothic , Kessel-Lo, 1993 .

- (fr) EVEN, Edward van. “The author of the 1493 altarpiece of the Hal Porte Museum in Brussels” , Bulletin of royal commissions of art and archeology 16 , 1877, p. 581 -598.

- (fr) Even, Edward Van. “Maître Jean Borman, the great Belgian sculptor at the end of XV It is century “, Bulletin of royal commissions of art and archeology 24 , 1884, p. 397 -426.

- (of) GOLDSCHMIDT, Adolph. Lübeck painting and plastic.

- (fr) Hainaut-Zveny, Brigitte d ‘. «La Dynasty Borreman ( XV It is – XVI It is S.): Genealogical pencil and comparative analysis of artistic personalities » , Annals of the history of art and archeology of the Free University of Brussels 5, 1983, p. 47 -66.

- (fr) Peronier-deterespers, Cathetlaine (you.). The altarpiece of the passion of the Sainte-Marie church in Gustrow. Historical and technological study , Brussels, ULB / Editechnart, 2014.

- (of) ROOSVAL, Johnny. Schnitzaltaren in Swedish churches and museums from the workshop of the Brüssler scanner Jan Borman. , Strasbourg, 1903 .

- (of) Schlie, Friedrich. The art and history monuments of the Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. Schwerin, 1901, p. 234 ff.

- (of) “Jan Borman” in Thieme-Becker .

external links [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

- Fine art resources :

-

Notes in generalist dictionaries or encyclopedias :

Recent Comments