Teke (people) — Wikipedia

For homonymous articles, see Teke.

THE Text – you tecé [ 5 ] – are Bantous from Central Africa, mainly of their population, in the south, to the north and center of the Republic of Congo, but also in the west of the Democratic Republic of Congo, and, minority, to the south -It of Gabon. The term BATEKE designates “the people of the teke”, the prefix not being the sign of the plural.

According to the sources and context, on observe of multipples variantes (CF. Polyonymy): Anzicana, Anzichi, Anzicho, Anzika, Anzique, Apostle, Baketi, Breasts, Tells, Bed, Mbeti, Tege, Tégué, Teché, Teché, Teché, Teché, Tella, Telle, Telle, Tege. Not, Teré, attracted, Oteré, Tio, Tsio, tyo [ 6 ] , Manjolo (au brésil) [ 7 ] .

Tékes were once known as “Anzico” [ 8 ] . This name appeared in 1535 in the titles claimed by Alphonse I of Kongo [ 9 ] . The term would be a pejorative designation used by bakongos and meaning “small” [ 8 ] , in reference to the pygmies with which the Tekes have mixed by spreading out on the ancient territory of these. Many other hypotheses on the etymology of Rather were issued by various authors without being more satisfactory.

They are often called today “Teké” (“Batéké” in Kikongo) or “Teke” according to Africanist spelling. In a way comparable to the ethnonym “Dioula” in Côte d’Ivoire, the term means or has taken up the meaning of “traders”.

Teké groups: Aboma, Akaniki, Foumou, Houm or Woum, Küküa (Kukuya) or Koukouya, Lali, Mfinou, Ndzikou, Ndzinzali, Ngoungoulou, Nguengué, Tégué, Tié, Tsayi (Tsaayi), Tswar. It should be noted that the spellings can vary a lot from one Western conqueror to another, and then with the scholarly distinctions [ ten ] .

They speak Teke languages [ 11 ] , which are Bantu languages.

We can distinguish around fifteen Metually intercomensible Teke dialects [ twelfth ] : ibelle Drove (BERVE CONFICIECION), IFoumu Nord, Iwouf Branzer, Polif (Nebouvie, Police) , Esyee, Gercaa u u uticté. Playele), guliwel (Gatuludes in Gambo, Plaeye (tereeye), ɲake 2ire, shoosing, fibrows, shoos, shoos, sandems, fibruel, firber. (boundji, Ewe Effico Ooro, albala). The series of the Bernis, djon and dye. [Ref. necessary]

The Teké are in the minority in Gabon, 54,000 are in the region of the Haut-Ogooué province, which constitutes their stronghold [Ref. necessary] . The late President Omar Bongo and the current president Ali Bongo are Teké.

It is in the Republic of Congo that they are the most numerous. Teké form 16.9% of the population. They are generally found in the very clear savannah regions of the sets, the department of Lékoumou, the West basin (where they are called Mbéti and Tégué), Niari, Bouenza and the Pool region [Ref. necessary] . Téke Tsayi occupy the forest on the eastern foothills of the Chaillu massif [ 13 ] .

In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, 267,000 Teké are installed in savannah regions in the district of the sets (located on the left bank of the Congo river, western part of the Bandundu province), and in the Kinshasa-Kinshasa city [Ref. necessary] .

Archeology [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

With the formation of a new grip of the forest under a climate that has become warm and humid (more humid than currently) in Central Africa, around 12,000-10,000 years BP, from the end of the Pleistocene, dry, at the start of the ‘Holocene, humid, a new lithic industry appears: Tshitolian [ 14 ] . This does not imply a uniform and regular phenomenon, but strong variations and local adaptations accordingly. There have only been a few traces of the former hunter-collection inhabitants, and their tools mark few differences with those of the end of the Pleistocene, the Lupembian industry. Locally, the assemblies in the northwest of the area are close to those found in West Africa, it is the same in the south with populations further south. Tshitolian, dominated with microliths, covers a large part of the Congo and certain areas of Gabon (the Batéké plateau), as well as west of the DRC, and northwest of Angola. These are broad spectrum, and mobile hunters. Tshitolian populations will leave traces of their activity in the Teké area for 10,000 years [ 15 ] .

In times following 7,000 BP, on the southeast border of Nigeria with Cameroon appear pottery, grinding and proof of fruit consumption Canarium schweinfurthii (Élémi, or Elemier). We meet other clues, thus large non -tshitolian bifaces and polished stone tools (with microliths). Later, these tools will be used to clear and gardening. This set will dominate the whole region during the following four millennia, while semi-domestic plants, such as oil palm, will be used abundantly. We deduce that these populations will be less mobile, more sedentary and more farmers, while a little less hunter-collectors. Banana and millet, however from Far East, appear in pits, west of Gabon and southwest Cameroon. Their dispersion to the south is probably to associate with the dissemination of Bantu languages. A dry climate period comes between 3,500 and 2,000 years BP in the Grassland (Cameroon) [ 16 ] . This episode, attached to overcrowding, could have determined the Bantu migration, from the Grassland, of these populations of cultivators with ceramic having, for some, the technology of iron – which appeared at the latest around 2150 BP, and came from Nigeria (culture Nok); It is also from Nok that the decorations with roulette would come from that we meet from this time on ceramics. The return of the populations to the Grassland would have limited reforestation, the dry episode passed [ 17 ] . The Batéké plateaus would, perhaps have crossed a similar sequence which would explain its current appearance.

On the Téké plateau, the steel industry widespread in the first centuries in our era. Agricultural tools, arrows and weapons employ iron. It is given a symbolic value, among others, in the cult of the dead. Then around the year 1,000 this activity increases clearly. Direct reduction low stoves are used in bowls dug on the ground. We activated combustion by a set composed of small bellows and terracotta nozzle. A stove, for single use, produced a few pounds of metal. Waste could be stored in mounds of slag, some of which correspond to the extraction of several tonnes of iron [ 18 ] .

Archeology has revealed, on the two banks of the Congo and Pool Malébo a rich ceramic tradition since the XI It is century, taking advantage of quality local clay. The quality of the sets and the finesse of this dishes manifest itself above all XIII It is At XIV It is century. It would be witnesses of the Téke Ndzindzali culture which would have developed for XI It is century. She would be the pombo mentioned by Olfert Dapper as having been a model for the peoples of the Atlantic coast [ 19 ] .

Ancient history [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

According to the founding myths, the Teké descend from Ngunu, ancestor of most of the populations of the South Congo.

At XV It is century, the Teké are established [ 20 ] In the savannah on the right bank of the Congo river. The heart of the kingdom being towards Mbé, it extends from the current cities of Kinshasa and Brazzaville, to the south, to the proximity of Ewo, to the north, then from the left bank of the Louessé near Mossendjo, at the ‘West, beyond the left bank of the Congo river, near Mushie, to the east, about 400 x 400 km.

The Teké drew their richness of important copper deposits at that time, like that of Mindouli. They have contacts with the Portuguese who explore the coastal region from the XVI It is century. They undergo the assaults of the Congo Empire, attracted by this source of profits and supported by the Kingdom of Portugal. A population, at the origin of the kingdom of Loango, hunts them towards the territory. At XIX It is century their space was reduced under the push of the Sundi, of the large Kongo group, by the Southwest and the South.

They are the successors of the pygmies in the occupation of the interior of the current Congo -Brazzaville – it is the pygmy which brings fire to the Teke. They emancipate from the political leader of the Kongo people, the manikongo at the XVII It is century and in turn founded the TIO kingdom. A rivalry is established with the Kongo which previously dominated this territory, then called Rather . The king is called mangroves or Makoko by Europeans, while the State is called the Kingdom of Anzique and the inhabitants Anzicains [ 21 ] .

Between the XVI It is and the XVIII It is century, the Teké kingdom is involved in triangular trade between Africa, Europe and European colonies in America and the slave trade [ 22 ] . This trade is accompanied by several others, at long distance, such as tobacco and ivory that Teké chiefs obtain pygmies. The iron trade produced by the forest Teké is carried out over hundreds of kilometers [ 23 ] . The steel industry is developing in Téke Tsayi with the arrival of a hero, who propagates variations in weaving techniques, but, at the same time, radically modifies the ancestral political system. Part of them escapes this break and develops other places of production. Clashes oppose Téké and Bobangui, who will culminate in 1820, with a victory of the Teké, near M’bé.

The Teke Tsayi had a two -headed political system: the which tsié , master of the earth, who has relations with the outside, trade, and the ta na , the master of people, from a society that preserves its sealing. With a strong distinction between Everfield , masters, and here , dependent-slaves. The tax war (1913-1920) ended this movement [ 24 ] .

Modern story [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

The explorer Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza left, in 1877, from the banks of the Ogooué river “in search of the lakes or the river through which the large mass of water falls under the equator”. He enters the Téke country and will reach the banks of the Alima, but he undergoes the attack on the Apfourou and must turn around. He undertook a second trip subsidized by the Ministry of Public Instruction as a representative of the Study Society for the exploration of Equatorial Africa. He founded Franceville in 1880, then entered the Téké country again [ 26 ] .

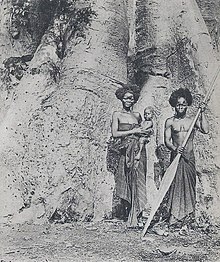

On October 3, 1880 in Mbé, in the city of which he is the makoko, Imubath Imumba I is Concludes with Brazza, acting on behalf of France, the so -called “Makoko treaty”, under which he places his kingdom under the protection of France. The treaty authorizes the establishment of the post of M’FA. Before the arrival of Europeans, the site, which was very busy, was a hub of trade controlled by the Teké. The place is located on the right bank of the Congo river, from Pool Malebo (Stanley Pool) to the first fast, at the break -up of several modes of transport, in the agglomeration of Nkuna and in the village of M ‘ FA (or MFOA), 500 kilometers from the last French station. In July 1881, the position was baptized Brazzaville. This position will be kept for years by a single sergeant, the Senegalese Malamine Kamara [ 27 ] . At the end of 82 a third trip is validated. The publication of the report of “Voyages to West Africa, 1875-1887” (The World Tour of 1887 and 1888) is accompanied by numerous engravings made from drawings based on the photographs taken by his brother, Jacques Jacques de Brazza, who had carried out a mission to the Téké country, on the banks of the Likouala in 1885. The Liane bridge on the Mpassa river, which he photographed in Téké country, was commented on by Brazza with admiration [ 28 ] .

The colonies had their own budget, fueled by direct tax per capita (difficult to set up in this unreteited or monetized company) and by customs taxes [ 29 ] . The economy of trafficking in agricultural products, in Central Africa, was supposed to be based on the exchange of manufactured goods imported for primary agricultural goods. In Téke country, they are large privileged companies (charter or dealership [ 30 ] ) Specialized in “picking” products, such as ivory and rubber. The colonials, isolated, had all the powers, the “natives” no [ thirty first ] . This situation leads, after the Casement report and the red rubber scandal in the independent state of the Congo which follows, then the Toqué-Gaud affair, to investigate, in France, in the noises of scandals similar to the French Congo. The taking possession of the territory was essential with the requisition of food, workers and carriers (among others, Batéké [ 32 ] ). The result of this investigation – the Brazza report -, conducted by Brazza and his team, will never be disclosed, too many people and interest in question, probably too many “unbearable” abuses for the image of France [ 33 ] . This report pointed out, among so many other facts, the questions posed by the tax, inconsistent, excessive, associated with forced labor (due to the regime of the Indigenous), and leading to armed expeditions to force tax to tax by force.

Some Teké still live, at the end of XIX It is century, in the independent state of the Congo, which in 1908 became Belgian Congo. At the beginning of XX It is century, most of the Teké groups lives on what the French consider two colonies, Gabon and the Middle Congo. Indeed, if in 1886, Gabon had become a colony, in 1888, it was merged with that of the Congo under the name of Gabon-Congo then, in 1898, French Congo. In 1904, following a decree of December 29, 1903, Gabon became a distinct colony, the rest of the French Congo forming the two colonies of the Middle Congo and Oubangui-Chari and the “Chad military territory”. In 1910, the colonies of Gabon and Congo were integrated into French Africa-Equatorial. The colonized populations are subject to the Indigenous regime until after the Second World War.

For centuries, the Tsayi Teké have detached the savannas to settle in the forest, in the eastern region of the Chaillu mountains. Colonial penetration, decided in 1909, led to a revolt proclaimed by all the peoples of this area, was followed by a repression, in 1913-1920, called “tax war”. The war, strictly speaking, was brief, and the country, after being subjected was abandoned due to the First World War. The tax war, in the Chaillu mountains (approximately between Mbinda, Mossendjo and Zanaga, a map above), was particularly brutal and brief, it led to the political and physiological distress of these populations, the abandonment of the villages, the ‘Wandering, famines and epidemics: sleep disease and Spanish flu of 1918. This disaster almost destroyed all Tsayi Téké [ 34 ] And the Nzebi people, in Gabon and the Congo Middle of the time. This war intervened while taxes increased and the populations suffered the dramatic decline in rubber prices (divided by 3 after 1911), a drop linked to the development of plantations of French Indochina, because from 1900, the culture of The rubber turned there a real commercial success. The Teké, in permanent motion to the Chaillu massif where some have stayed in Gabon [ 35 ] . Many came to die of hunger so as not to submit, not having enough to pay the tax and feared the reprisals of the troop. At the end of this war Téke Tsayi, to name a few, lost the nine tenths of their population.

Everyday life [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

A large part of the Teké lives on sets, between 300 and 900 meters above sea level, in an almost desert sandy savannah as well as platforms listed since 2005 on an indicative list, with a view to its classification as World Heritage of Humanity UNESCO [ 36 ] . It is an apparently inhospitable environment, women walk several hours a day to bring essential water, the port is essential, the network of trails cuts through giant and hurtful grasses [ 37 ] .

The medium -sized village was limited, at the end of XX It is century, at a dozen homes and around thirty people, some animals, dogs and hens. The places of housing, vegetable constructions of reduced and smoky sizes, had to be rebuilt nine every three or four years. The furniture was summed up in log beds with braided mat, some basketry objects and pottery. The absence of a food reserve corresponded, then, to a decline in corn in favor of cassava.

The arts of the body manifested themselves with real diversity. Facial scarifications, incised around three years, were not general and varied according to the groups. Some covering their body with palm oil shaded in red. The development of complex hairstyles occupied part of the free time.

In this context, frugality was an ideal lived on a daily basis; Well-being showing itself in the health and fertility of men and nature, which depend on the goodwill of invisible forces, spirits of waters, trees and rocks, spirits of the deceased. The only collective wealth depended on the number of humans. The race for material, individual wealth seemed suspicious and dangerous there: “Material goods are reduced to nothing by accompanying the deceased in the earth during grandiose funeral [ 38 ] . ».

The fire was essential. In the etiological stories of Tsayi Tékeyi it is a pigmy that invents fire. The fire arts appear one after the other, first the driving fire, for weaving, the one that cooks, for ceramics, and the one that transforms, for metallurgy.

Each village had several weaving trades, sheltered, made available to craftsmen. From the top of the palm trees we recovered the flock, put to dry in the sun and fire before drawing strands. The pineapple leaves also supplied an appreciated fiber. The weaving was carried out on a vertical profession at a rank of smooth, a loom that the Nzebi borrowed them. Each woven part covers, then, about 50 x 70 cm, which will be sewn between them according to the use. Fineness, the colors obtained by dyeing, the fringes offer different quality criteria. Téke Koukouya would have been the first to produce a form of velvet in polychrome patterns [ 39 ] .

Art and society [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

Before colonization and until the beginning of XX It is A century, the achievements of the Teké are of high quality and in direct connection with their culture, with their society.

Metal arts [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

The whole region is particularly rich in minerals, the Batéké plateaus having always known for their iron ore [ 40 ] .

Certain objects, such as the torques, necklaces of brass chefs, were made at the request of Westerners at the end of the XIX It is century according to the originals they saw, including that executed for Jacques de Brazza in 1884 (Paris, Museum of Man [ 41 ] ). Many iron weapons were parade objects; Certain weapons specific to Téke, knives with curved blades, sharpened on the convex side. The oldest, whose forged blade is not smooth, have a potato with decoration fixed with iron staples, others with brass upholsterers, western. A drawing by Jacques de Brazza from 1883 shows this type of knife, held in its case, under the left axrait [ 42 ] . The iron, in the shape of a ball, was produced for centuries by the Téke Tsayi and Lali des Monts du Chaillu, and exported to hundreds of kilometers before being shaped. The blacksmith was master blacksmith and also, “forced spirits [ 43 ] ». He had an anvil often in stone, a small home on the ground and a bellows activated by an apprentice. His mastery led him to practice in other fields, the realization of pipes, even in ceramic, he was an expert in the handling of tools, even scarifier or sculptor on wood, “always close to healers, and never distant from political power [ 43 ] ».

-

Brass chief necklace [ 44 ] .

-

![Appuie-tête. Bois, punaises laiton, fer. 15.0 x 16.5 x 11.3 cm. RDC (?). 19e-déb. 20e[45]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5e/Brooklyn_Museum_22.1270_Headrest.jpg/179px-Brooklyn_Museum_22.1270_Headrest.jpg)

Headrest. Wood, brass bedbugs, iron. 15.0 x 16.5 x 11.3 cm. DRC (?). 19 It is -Deb. 20 It is [ 45 ]

-

Curve blade knife. Iron, wood, brass. Congo or DRC [ forty six ] .

Daily life arts [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

The headrests were necessary before European penetration to preserve the elaborate hairstyles. They are of a sober and elegant drawing, or play the “carrier whose head is the headrest” in a perfectly balanced geometric style. One of them serves as an emblem at the Dapper Museum. The combs were used above all to make spectacular hairstyles on a circular frame, mwou , or huge crests, mou-pani [ 47 ] . »

The potters achieved their own ceramics, cooked on bare fire. Most of these pottery were mounted at Colombin, but sometimes it was a ball of clay that was dug. The assembly of two parts made it possible to obtain closed forms. Incisions or prints can decorate the walls. Some were decorated, from the XIX It is century, red or orange bands. Remove from the fire, still burning the pottery were shaded in black and waterproofed by a bath of palm oil or by projection of a decoction of bark. After 1930, potters produced extraordinary forms for passing tourists [ 48 ] .

Statues and statuettes [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

Europeans quickly confused under the term “fetish” of the characters whose functions and the work escaped their understanding. They could be advisers and personal doctors of the representatives of political power, sosets, shamans, healers or even general practitioners or specialists. In any case, they were attentive and curious characters with all effective novelty. They were always required to success, or to healing, and were only paid after. For this purpose, they gathered everything that represented, in the most concentrated way, “the invisible forces, designated as an mind of nature or ancestors [ 49 ] . », Benevolent or malicious spirits that it was a question of knowing and thus acting accordingly.

Teké statues and statuettes measure between 50 and 10 cm high [ 51 ] . The classic style statuettes of the right bank of the Congo river have, like most of the Teké statues, a cavity on the belly which can receive a composite substance, a magic load which devotes it to a magical, protective function, coated with a fabric blue. But sometimes the statuette is simply taken in a kind of conical “pottery” reddish. The character carries a hat represented in the old teké sculpture, in the shape of a tray surmounted by a ridge [ 52 ] . A beard expressed by a trapezoidal shape evokes, by amplifying it, the short bearded that dignitaries carried such as the Makoko of Mbé Illoy Loubath Imumba. The load in clay, even in palm oil and crushed red wood, mixed with other components, serves as a medication [ 53 ] . Sometimes it could take the place of protection brought by the living head of family, or any other eminent deceased character.

A village chief who owned the art of healing could sculpt or command sculpture, but, as a practitioner it is he who devoted this sculpture by loading it with its power, to the components chosen for their supposed efficiency [ 54 ] . Current diseases, such as sleep disease, could give rise to such objects.

For neighbors, like the Sundi (Sound), one could give the statuette the appearance of a Sundi rather than a teke by obvious signs, like the hairstyle [ 55 ] , maybe also the headdress (?) [ 56 ] .

Relations between neighboring populations, in a more or less difficult time to determine, sometimes manifest in the form of exchanges of sculptural solutions. Thus on certain statues of Teké size and morphology, the fitting between the cheeks and the neck seems to be inspired by the solution present in the large female statue of the Yanzi, which were neighbors of the Téke on the left bank of the Congo river, while The Teké were installed on both banks. In the opposite direction, it would not be impossible that the long scarifications of the Teké were transposed in this statue [ 57 ] . A loan could also be motivated by the desire to increase the efficiency of what was shaped.

Paintings of Téké Tsayi [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

The paintings occurred on Kidoumou masks and on the boards mboungou of the Nkita ritual, essential during certain Tsayi rituals.

The west Teké, Teké Tsayi and Lali, live in the forest, in the region between Bambama, Komono, Mossendjo and Mayoko, in the Republic of Congo, a square of about 100 km. next to [ 58 ] .

Maybe at the start of XVI It is A century, Tsayi migrated to the west to flee an overly powerful makoko. They left the savannas for the Chaillu mountains forest. They were numerous and traded the woven iron and raffia. The Tsayi first exploited the rich iron of iron ore in the northeast of Komono, the Zanaga mines, east of the Tsayi area [ 59 ] . Power was traditionally balanced between master of the earth and master of men. At the beginning of XVIII It is century or before, a hero, of Teké Küküa origin, introduced an authoritarian regime which destroyed the previous balance by suppressing the role of the master of the earth. The western part kept its operating mode, developed with the exploitation the less rich deposits of Mont Obima (dep. Lékoumou), towards Mbinda. Trade, the milking, intensified there from 1815. For the Téke this intensification resulted in the arrival of groups of Kota warriors who picked up their way to the Atlantic. The invention of the Kidoumou, around 1860, at Mount Lékoumou, would first be a peaceful response to this different culture which was breaking, then and above all the affirmation of the duality of power by a round mask in two symmetrical parts Who would dance, by making “the wheel”, to emphasize its deep meaning.

Until 1920, southern Gabon, on the border, served as an ultimate sanctuary for Tsayi, rebellious despite the tax war. The forest corresponds to the tank of a certain type of Kidoumou mask, the so -called Lékoumou style masks [ 60 ] . The Lékoumou deposit (department of Lékoumou) was rich, and its exploitation stretched to Youlandzami, a large village south of the Siniga-Louessé confluence.

Masque kidoumou [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

The wooden part of the mask is in the shape of a disc, and differs in every way Kota masks. This disc [ sixty one ] is painted in mineral red, black and white, in graphic shapes, redoubled by deep incisions. He is a face in a “abstract” way, which fascinated modern Parisian artists [ 62 ] . It is divided in half, horizontally. Left/right symmetry is coupled with high/low symmetry. It’s “a kind of horizontal Janus”. And yet some signs come out of symmetry. They discreetly oppose the top and lower face. At first glance, only the eyes are visible, everything else is “abstract”. And yet these eyes are blind, they do not coincide at all with the small slots that allow the dancer to see and move. The slots are hidden, completely invisible, in a double level of level between the upper and lower halves. A large “hair” of feathers surrounds it, redoubled by a wider “beard” of raffia which descends to the shoulders. Kidoumou’s acrobatic dancer also has a raffia garment that covers it entirely. He makes the wheel: a high and low moment are reversed, only a moment the dominant goes downstairs. The choreography is full of meaning and at high risk, because the mask increases by its hair and its beard, barely holds by a lace between the teeth of the dancer. It is a brilliant manifestation of Téké cultural genius. Three came to the first cultural week of Brazzaville in July 1968, and they did not come from Bambama (Lékana) who had refused to move. The choreography which took place in 1969 was accompanied by singers who beat hands, and by an orchestra made up of three drums, a double bell without a beating and another, simple, struck by a wooden rod [ 63 ] .

Another origin of Kidoumou masks gives some of them large “eyes” which spread from one edge to another [ sixty four ] , [ 65 ] .

The peak of the Kidoumou mask corresponds to the period when the Teké (and their allies) formed a rich and active set. This mask still appears during the tax war, after which it is only a memory in the memory of some Teké specialists.

This mask is sometimes accompanied by another, Sanga, which wears a veil on a long dress that drags and swirls. Another version of the origin of Kidoumou places the latter in the evolution of the veiled Mask Sanga, which is anterior to him [ 66 ] .

In 1967, as part of an ethno-aesthetic research following the study of the social and political organization of the Tsayi [ sixty seven ] , Marie-Claude Dupré photographs a mask, which had not been made to dance, but to keep the memory, after the sale of the previous [ 68 ] .

“In 1968, on the occasion of the inauguration of the railway which evacuated manganese, passing through the Bambama region, and with the creation of an administrative position in Bambama, three Kidoumou” went out “, three masks are Alleged in Brazzaville, the cultural week of July 14, 1968. There were two broadcasting households in 1968. One of the two households in the south, (in Mbama?) Those who went to Brazzaville, and one of them , who had not finished his mask refused to sell him and completed him with his home. I had the chance to photograph the 2 versions. »»

It was to the master of the earth, in this case that of Bambama, which he returned to bring out the Kidoumou mask in October 1969: for the resolution of a conflict between the same master of the earth and one of his dependent . It is therefore a political mask – and not “animist” or “religious”.

But this mask had not danced for almost 20 years. The second diffusion household was, still in 1968, on two places: in Bambama, with the village (suburb) of Lékana, the most traditionalist, and in the village of Kiboungou with rather rustic masks of this style.

The Kidoumou mask was, then, a rare mask which only came out very exceptionally. The research conducted on this mask by ethno-esthetician and published in 1968, found an echo in the local administration which requested the production of several hundred masks, carried out according to tradition, from memory from old models, different. They were intended for the art market. However, the diffusion in the form of drawings, from France, of the “old” masks published in the thesis, have led to copies, smeared with colors, and to the extension of the production places outside the Téké country until, Finally, market saturation [ 69 ] .

Painted board mboungou [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

First of all the mind must Inkita manifests itself in a woman. If it did not come forward, we would not use mboungou . Because it alone will then be likely to use the board.

On August 15, 1972 in Zanaga, when she released the imprisonment, the young Nkita, sumptuously adorned, offered herself to the admiration of the crowd. She was supervised by her “mothers”. She entered a trance, and had to be accompanied with care. Then the party continued, to the sound of the pluriac played by a pygmy. On another occasion, described by the missionary Siegfrid Sodergren [ 71 ] The dance that leads the village does not interrupt that of Inkita women, accompanied to the trance by a numerous orchestra and composed of stringed rope instruments, pods of seeds and rattles.

The women affected by the Inkita spirit are reclusions in a small building, a little away from the dwellings. The board is the one that borders her bed.

The boards of the ritual bed strike by the intensity of their colors: the guimet blue known for the azureage by the whitens, alternates with white and red ocher, elsewhere black and red brown play with pure white. The color placed in the incisions keeps all its intensity for a long time, while the other colors will diminish in use. The plates are composed according to a regular rhythm by vivid incisions and colors, from the “heart”, the center or the “navel”, then towards the right side, that of man, or the reverse, from the left side, that of the woman [ 72 ] . The center can also be empty, or simply signified by a line between the two spaces. Horizontal symmetry is most often found; The patterns of the Kidoumou mask logically find their place there. The snake or the turtle become purely graphic patterns. But the herminettes which are used to make the boards, the knife, even the agricultural knife must insert subtly among the abstract patterns which echo them. The effects of symmetry are not systematic, on the contrary, the offsets, the counter-time games and the local asymmetries create more or less balanced “abstract” compositions or in tension. Finally, the solution of a disorder area can find its place, punctually, but sometimes it is only only systematic throughout the length of the paint. According to the authors of these paintings, you have to see stories in pictures. Everything seems to happen in the world of creative spirits.

Twins in Teké culture [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

L’Onkira [ seventy three ] is the ritual celebrating the arrival of twins. In a tegue country, the birth of twins is a happiness but dreaded happiness. Their interviews are also called Ayara (plural) and Yara (singular) and their worship Oyara. As soon as the world arrives, twins learn to walk in a special enclosure. During all this time, strict respect for several natural and human laws under the observation of parents and other individuals. When we talk to the twins, you have to address the two, or else, if you want one, you have to ask the other agreement. No gift to one of the two, never in a different dress style before the age of 15. The parents of the twins are very respected in society. These are the Tara Ayara or Tara Ankira (father of the twins) and Ngou Ayara or Ngou Ankira (mother of the twins). The dancing of the ritual of twins is called Lama. This dance is considered to be the mother of all the dances and it was she who gave birth to the famous Dance Tégué Olamaghna. Thus, the Onkira Tegue to which the twins belonged and their parents belonged. Also born in this veneration of twins, a calendar and the award of names. The first born is Nkoumou , mbou,mo, ngambouu or Ngambio And Mpea, Clash, Black, Ngamkika or Mpi For the second. The one who follows twins in the order of birth is called Lekogho or Lakogho and the fourth Nut .

The weaving of raffia, practiced in many regions of sub -Saharan Africa, is known to most of the populations of the Congo basin. Although, in general, the old -fashioned current production, the manufacture and the use of raffia tissues keep in certain regions an important ritual character cannot be compared. Among the Batéké the loincloth of Raphia an essential object for customary marriages and burials. All the more these raffia fabrics were the main object of external exchange with the Mbochi, the Tékes of the Alima, the Koukouya ..

There are several types of raffia weaving in batéké: powers or nzana (house four) when they are folded down [What ?] and that the whole is normally hell, bread when the free part of each band ends with a fringe; It is reserved for heads of families and notables. When it is not united, the loincloth carries the dominant color of its stripes, the name of the animal which is supposed to have transmitted to men the shade considered; nzoana-ben , a loincloth where the red is dominant, Well or “The frog”, a loincloth where black is dominant; Impalapala or “the lizard” a loincloth where the gray is dominant and lime So called because of its making which highlights protruding streaks comparable to that of a file, loutsoulo , woven in a coupon to constitute a loincloth. The other raffia loincloths are pogo , loincloth reserved for the dowry, Ana , Raphia cover sometimes carried by women around the arm.

In addition to the raffia, there are velour effect multicolored fabrics such as the ntâ-ngò (pronunciation: when) [ 74 ] , the loincloth of the panther, decorated with the pattern of the panther, the representation of cassava fields, flowers and sometimes the objects of power most often red color is also found in gray, blue and brown. These patterns can also be gray in color. This remarkable product is reserved for the so -called “lords” mfumu a yulu and “Lords of the Earth”, said The king of the osè , and the self -employed, said diply . They alone have the right to hold the ntâ-ngò in their homes.

There are also a lot of female and male accessories, bells, raffia caps and feathers, baskets, baskets, hunting, calabasses, brooms…

- Janis Otsiemi, Gabonese writer

- Omar Bongo Ondimba, Gabonese politician

- Lambert Galibali, Policy Du Cogo Brazzaville

- Patience Dabany, Gabonese musician

- Gabriel Okoundji, Congolese poet and writer

- Ndouna Désnaud, Gabonese poet and writer

- Illoy Ier, Makoko of BEI

- Ngalifourou (1879-1956), queen of the Téké kingdom

- Hopiel Ebiatsi , Congolese historian and writer

- Eugénie monayini opou , Congolese writer, poet and novelist

- Serge Ibaka Ngobila, player basket congolais

- GENTINY NGOBILA (Mary de Kinshasa)

- Pierre Mombele (DRC politician). He was the president of the Bateke Union and participated in the Brussels round table in 1960.

- Stervos Niarcos, Adrien Mombele Nganthie was a Congolese singer and songwriter and songwriter.

- Ngaliema Insi, also called Mukoko, which means “prince” is a land chief and one of the many brothers of King Makoko.

- Beach Ngobila, issu of the chief Ngobila who reigns on Nshasa, today Kinshasa.

- “Makoko” is a title, it is not the name of a person (M-C Dupré and E. Dégau, 1998, p. 31). If we want to force the comparison, it could be a term “approaching” “king”.

- Source https://www.britannica.com/place/democratic-republic-OF-the-congo/peove , estimation 2021

- Source CIA The Word Factbook

- Source CIA The Word Factbook

- Larousse encyclopedia.

- Source branch, bnf [first]

- (pt-br) ‘ Slave trade: Africans brought to Taubaté » , on Urupês Almanac , (consulted the )

- Th. Simar, The Congo at XVI It is century according to the relationship of Lopez-Pigafetta , p. 79 & sq. Simonetti, Brussels, 1919

- Louis Jadin and Mireille Dicorato, Correspondence from Dom Afonso, King of Congo , Brussels, 1974.

- M-C Dupré and E. Dégau, 1998, p. 15 not paginated, card.

- ‘ Teke languages » , on IDREF.fr

- Jean-Pierre Missié, ” Ethnicity and territoriality », African study notebooks , n O 192, , p. 835-864 ( read online , consulted the ) .

- M-C Dupré, 1990, p. 59

- (in) Karen Lupo, Chris Kiahipes et A. Jean-Paul Ndanga, ‘ On Late Holocene Population Interactions in the Northwestern Congo Basin : When, how and why does the ethnographic pattern begin ? » , 2013 env. (consulted the ) . See as well : (in) Peter N. Peegrine (ed.), Scott McEhern et al. , Encyclopedia of prehistory , vol. 1, Elsevier, , 28 cm. (9 vol.) (ISBN 978-0-306-46255-9 And 0-306-46255-9 , read online ) , « Central africa : Forageres, farmers and metallurgists » , p. 278-286 .

- M-C Dupré and E. Dégau, 1998, p. 43 and Raymond Lanfranchi, Dominique Schwartz (ed.) Et P. de Maret, Quaternary landscapes of Atlantic Central Africa , Ed. Orstom, ( read online ) , “The” Neolithic “and the Ancient Iron Age in the southwest of Central Africa” .

- Lupo (et al.), 2013 ENV. and Alain Froment, Jean GUFFROY ( you. ) and Philippe Lavachery, Ancient and current stands of tropical forests (1998) , Paris, IRD ed., , 358 p. , 24 cm (ISBN 2-7099-1534-0 , read online ) , “At the edge of the forest 10,000 years of interactions between humans and the environment in the Grassfields (Cameroon)”

- Philippe Lavachery, 2003

- Bruno Pinçon in M-C Dupré and E. Dégau, 1998, p. 43

- Bruno Pinçon in M-C Dupré and E. Dégau, 1998, p. forty six

- They have been established there for five centuries and more: M-C Dupré and E. Dégau, 1998, p. 42

- Olfert Dapper, Description of Africa .

- Isidore Ndaywel, Slavery and treats: why blacks and not others? , The potential.

- Bruno Pinçon in M-C Dupré and E. Dégau, 1998, p. 48

- M-C Dupré, 1990

- Dating attributed according to the photographer’s biography

- M-C Dupré and E. Dégau, 1998, p. thirty first

- J.- Roof, A legendary explorer , in Adventurers of the world – The archives of French explorers – 1827-1914. , The iconoclast, Paris, 2013 (ISBN 978-2-91336-660-2 ) , p. 117.

- Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza ( pref. Chantal Edel et J.P. Sicre, ill. Riou, Barbant, Thiriat), In the heart of Africa 1875-1887 , Paris, Phébus, ( first re ed. 1888, published in Around the world ), 206 p. (ISBN 2-85940-244-6 ) , p. 192 (e.g.) . Read online p. 51, on the site of the French Institute: Fond Gabon.

- Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch, Little history of Africa: Africa south of the Sahara, from prehistory to the present day , Paris, La Découverte, 2011-2016, 226 p. (ISBN 978-2-7071-9101-4 ) , p. 170

- Concession map of 01-01-1900: History of Central Africa, origins in the middle of XX It is century , African presence 1971, p. 186. No concession indicated in Téke country, north and west of Brazzaville.

- Coquery-Vidrovitch, 2016, p. 173. See also, although different: Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch The Congo at the time of major concession companies: 1898-1930 , EHESS open-publishing.

- The illustrated world , 1884: engraving reproduced in M-C Dupré and E. Dégau, 1998, p. thirty first

- Mission Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza / Commission Lanessan ( pref. Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch), The Brazza report, Congo Investigation Mission, Report and Documents (1905-1907) , Paris, the clandestine passenger, , 307 p. (ISBN 978-2-36935-006-4 , read online ) : Online presentation on Fabula. The question of tax: p. 112-113.

- Marie-Claude Dupré, ” The tax war in the Chaillu mountains. Gabon, medium Congo (1909-1920) », Overseas. History review , n O 300, , p. 409-423 ( read online , consulted the ) And Marie-Claude Dupré, ” A demographic catastrophe in the Congo Middle: the tax war among the TSAAYI Tékeayi, 1913-1920 », History in Africa , vol. 17, , p. 59-76 ( read online , consulted the )

- M-C Dupré, 1990, p. 65

- UNESCO Heritage Center world , ‘ Batéké Plateaux National Park – UNESCO World Heritage Center » , on UNESCO World Heritage Center , (consulted the )

- Bruno Pinçon in: M-C Dupré and E. Dégau, 1998, p. 58-61

- Ditto, Bruno Pinçon, p. 60.

- Ditto, Bruno Pinçon, p. 61.

- Pierre serve, « The mining economy of the People’s Republic of Congo », Overseas notebooks , vol. 26, n O 102, , p. 172-206 ( read online , consulted the ) . Card p. 174.

- Torque made for Jacques de Brazza in 1884 in Ngantchou , Quai Branly Museum.

- M-C Dupré and E. Dégau, 1998, p. 108-111

- M-C Dupré and E. Dégau, 1998, p. sixty four

- Royal Museum of Central Africa

- Brooklyn Museum

- Ontario Royal Museum

- M-C Dupré and E. Dégau, 1998, p. 77.

- M-C Dupré and E. Dégau, 1998, p. 62-63 and p. 82

- Marie-Claude Dupré in: M-C Dupré and E. Dégau, 1998, p. 242-267

- Sessions pavilion. Louvre.

- Étienne Dégau in: M-C Dupré and E. Dégau, 1998, p. 124 and following. They can reach 80 cm, like that of the Dapper Foundation: Christiane Falgayrette-Leveau ( you. ) et al. , Afriques: artists of yesterday and today: Clément Foundation , Hervé Chopin, Clément Foundation, Dapper Foundation, , 240 p. , 30 cm (ISBN 978-2-3572-0361-7 ) , p. 52-53

- See the notice of the Assisi male statuette , with the “Description” and “Use” sections.

- Doctor Mense, in 1887: M-C Dupré and E. Dégau, 1998, p. 172

- Étienne Dégau, in: M-C Dupré and E. Dégau, 1998, p. 126-129

- The colonial administrator Kiener, stationed in 1913, published a study which is mentioned in M-C Dupré and E. Dégau, 1998, p. 128: The Sundi / Téké difference manifests in the hairstyle, “Batéké stretches the skin from the skull and folds it over itself to form a crown; The bassoundi brings all his hair back to the median part of the head and the helmet -shaped comb ”.

- The notice written by the Quai Branly museum, about a Teké statuette, evokes a headdress: The character carries a hat very often represented in the Téké sculpture. Museum page , see tab “Description”.

- Marie-Claude Dupré in: M-C Dupré and E. Dégau, 1998, p. 222-223

- M-C Dupré, 1990, p. 450

- M-C Dupré, 1990, p. 447

- M-C Dupré, 1981, p. 121 who refers to collectors-historians.

- Several old versions have various “original” variants “. Marie-Claude Dupré points out that a master of the land will order, on a certain opportunity, to one of his friends, who sent a young parent, sportsman with another sculptor-dancer who will serve as “coach”. Back, the young person will be sculptor of memory (the variants always appear), he will cut his costume and become a dancer of the mask. See the copy described by M.-C. Dupré: [2] .

- André Derain had one which is currently kept in the collection of the Barbier-Mueller Museum in Geneva.

- Marie-Claude Dupré in: M-C Dupré and E. Dégau, 1998, p. 245

- Marie-Claude Dupré in: M-C Dupré and E. Dégau, 1998, p. 248; See as well Marie-Claude Dupré, ” A “heritage” exhibition in Paris: Batéké, painters and sculptors from Africa and Central », French ethnology “Museum, nation: after the colonies”, , p. 461-464 ( read online , consulted in ) .

- ‘ Historical » , on Barbier-Mueller Museum, Geneva (consulted the ) : photo, “facial mask. TEKE, TSAAYI group, Republic of Congo. Polychrome light wood. H. 34 cm. Anc. coll. André Derain, Charles Ratton and Josef Mueller. Inv. 1021-20. Barbier-Mueller Museum. Ferrazzini Bouchet studio photo. »»

- Marie-Claude Dupré in: M-C Dupré and E. Dégau, 1998, p. 247

- This research is in the methodological heritage of Pierre Francastel, “comparative historical sociology”. M-C Dupré, 1981, p. 106 in Ref. To Painting and society , Gallimard, Ideas / Art 1965, p. 52: “Art explains, in part, the real springs of society”.

- M-C Dupré, 1981, p. 105

- Marie-Claude Dupré in: M-C Dupré and E. Dégau, 1998, p. 244-245. Drawings reproduced p. 298 (Photography of 1972).

- Quai Branly Museum

- M-C Dupré, 1981, p. 268-273

- Marie-Claude Dupré in: M-C Dupré and E. Dégau, 1998, p. 276 and 276-295

- ‘ Memoir online – Traditional beliefs of the Alima tege and Christianity (1880-1960) – Louis PRAXISTELLE NGANGA » , on Online memory (consulted the )

- Pierre Bonnafé « A great feast of life and death: the Miyali, funeral ceremony of a lord of heaven Kukuya (Congo-Brazzaville) », Male , vol. 13, n O 1, , p. 97–166 (DOI 10.3406/him.1973.367331 , read online , consulted the )

Bibliography [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

- Willy Bal, The Kingdom of Kongo to XV It is And XVI It is centuries , African presence, , 124 p. , 24 cm . See as well The Kingdom of Congo & the surrounding regions (1591) , the description of Filippo Pigafetta & Duarte Lopes; Translated from the Italian, annotated & presented by Willy Bal, Paris: Chandeigne: Ed. UNESCO, 2002. (ISBN 2-906462-82-9 )

- Pierre Savorgnan de Brazza ( pref. Chantal Edel et J.P. Sicre, ill. Riou, Barbant, Thiriat), In the heart of Africa: 1875-1887 , Paris, Phébus, ( first re ed. Passage published in Around the world In 1888), 206 p. (ISBN 978-2-85940-244-0 And 2-85940-244-6 , read online ) , p. 183-191 . Online on Gallica (poorly reproduced engravings): 1887 and 1888, Research Brazza, 1887 (p. 305-320) and 1888 (p. 1-64). See also text and good engravings: 1888 / Téké: PDF , pages 49, 52 and 54-59.

- Hubert Deschamps, Oral traditions and archives in Gabon. Contribution to ethno-history , Paris, Berger-Levrault, , 172 p. , 23 cm. ( read online ) , p. 61-64 , the article «Tecé»

- Marie-Claude Dupré (drawn from: “Antologia di Belle Arti”, (1981), vol. 5, n. 17-20 (p.105-128)), Art and History among the Tsaayi Tékeayi of Congo , Editrice Society Umberto Allemandi & Co (?), (ISSN 0394-0136 ) , p. 121

- Marie-Claude Dupré, ” About a Mask by the west Teké (Congo-Brazzaville) », Objects and worlds: The Revue du Musée de l’Homme , vol. 8, n O 4, , p. 295-310 ( read online , consulted the ) .

- Marie-Claude Dupré, ‘ Dance masks or geopolitical cards? : Kidumu’s invention among Tsayi Teké at XIX It is century (People’s Republic of Congo) » , on Horizon full texts, research institute for development , (consulted the ) .

- Marie-Claude Dupré and Bruno Pinçon, Metallurgy and politics in Central Africa: two thousand years of vestiges on the Batéké, Gabon, Congo, Zaïre sets , Paris, ed. Karthala, , 266 p. , 24 cm. (ISBN 2-86537-717-2 , read online ) : Online, large extracts.

- Marie-Claude Dupré, ” The agricultural tool for forest essartages: culture knives in Gabon and Congo », Notebooks of the Institute of Method , n O 2, , p. 3-77 .

- Marie-Claude Dupré (Commissioner), Étienne Dégau (Commissioner), Bruno Pinçon, Colleen Kriger and Sigfrid Södergren (exhibition catalog: Paris, National Museum of Arts of Africa and Oceania, September 30, 1998-4 January 1999) ,, Batéké: painters and sculptors from Central Africa , Paris, Paris: meeting of national museums, , 300 p. , 28 cm. [ill. in black and slot. Bibliography] (ISBN 2-7118-3567-7 ) . Press release: [3]

- Ethno-pastoral study week, Social and political organization among the Yansi, Teke and Boma: reports and reports of the IV It is Ethno-pastoral study week , Bandundu (Zaire), Center for Ethnological Studies, , 194 p. , 26 cm.

- Raoul Lehuard, « Stanley-Pool statuary: Contribution to the study of the arts and techniques of the peoples Téke, Lari, Bembé, Sundi and Bwendé of the People’s Republic of Congo », Black Africa Arts , , p. 184 .

- (in) Scott Maceachern (Africanist archaeologist, Duke Kunshan University (in) ), Central Africa : Foragers, Farmers, and Metallurgists : Great Lakes Area, Sudan, Nilotic Zimbabwe, Plateau and Surrounding Areas (PDF) , Elsevier, ( read online ) : article : Tshitolian .

- Theophilus call, The Teke people in Central Africa », MUNTU, scientific and cultural review of the CICIBA / Center International des Civilizations Bantu , n O 7, (ISSN 0768-9403 , Salt B005KGQBY8 ) .

- Theophilus call, Introduction to the knowledge of the people of the People’s Republic of Congo , University of Brazzaville, laboratory of cultural anthropology, , 148 p. , 31 cm

- Theophilus call ( you. ) ( pref. Denis Sassou N’Guesso), General history of the Congo from origins to the present day , Paris: L’Harmattan, 2010-2011, 284 p. , 22 cm (ISBN 978-2-296-12927-6 , 978-2-296-12969-6 , 978-2-296-13628-1 And 978-2-296-54367-6 ) (4 tomes)

- EbotSSSAI-HOPIEL-Opienge, Tekes, peoples and nation , Montpellier, Montpellier : Ebiatsa-Hopiel, , 81 p. , 21 cm. (ISBN 2-9501472-1-6 , read online )

- Eugénie monayini opou, The Teké kingdom , Paris/Budapest/Torino, L’Harmattan, Paris, ( rompr. 2013), 151 p. , 22 cm (ISBN 2-7475-8541-7 , read online )

- Eugénie monayini opou, Queen Ngalifourou, sovereign of Teké: last sovereign of black Africa , L’Harmattan, Paris, , 238 p. , 22 cm (ISBN 978-2-296-01310-0 , read online )

- Bakonirina Rakotomamonjy (Coordination Ensag), ‘ And Domaine du The Best Of Domaine, Congo Brazzaville » , on ENSAG, Craterre Éditions , (consulted the )

- Alain Roger (thesis), Teké art, ethno-morphological analysis of statuary , University of Paris 7, ( rompr. 1993, Lille: National Workshop for the Reproduction of theses, microfiches), 335 p.

- (in) Jan Vansina, The Tio kingdom of the middle Congo 1880-1892 , Oxford University Press, , XVI- 586 p. , 22 cm (ISBN 0-19-724189-1 ) . Report by M-C Dupré

Related articles [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

external links [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

- Fine art resources :

- Music resource :

-

Notes in generalist dictionaries or encyclopedias :

- Hearth : All about the Teké ethnicity in Gabon On Amazing Gabon

- (is) Pueblo they shook

![Collier de chef en laiton[44].](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5c/Collar_for_chief%2C_brass_-_Teke_-_DRC_-_Royal_Museum_for_Central_Africa_-_DSC07146.JPG/294px-Collar_for_chief%2C_brass_-_Teke_-_DRC_-_Royal_Museum_for_Central_Africa_-_DSC07146.JPG)

![Couteau à lame courbe. Fer, bois, laiton. Congo ou RDC[46].](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/1b/Knife%2C_Teke%2C_Democratic_Republic_of_the_Congo%2C_late_19th_century_-_Royal_Ontario_Museum_-_DSC09593.JPG/130px-Knife%2C_Teke%2C_Democratic_Republic_of_the_Congo%2C_late_19th_century_-_Royal_Ontario_Museum_-_DSC09593.JPG)

Recent Comments