TidAraya sōtatsu – Wikipedia

Sōtatsu , nickname: Inen , workshop names: Tawara-y And Taiseiken , generally called Tawaraya Sōtatsu, is a Japanese painter of XVI It is – XVII It is centuries, from the Rinpa school. His dates of birth and death are not known but his birth at the end of XVI It is century according to the dating of his work, and his death was around 1643. One of his works was dated 1606, and the restoration works of a precious collection which was entrusted to him in 1602, suggests a date of birth towards the end of XVI It is century.

The feudal regime firmly established by the Shogunal Government of Tokugawa and supported by the development of industry and trade, ensures a peace that lasts for two and a half centuries. No longer having to fear interior disorders or foreign invasions, the different social, military, aristocratic or bourgeois classes, call on artists of very diverse tendencies to satisfy their need for works of art. At the same time as Edo stands out as a political center, ôsaka affirms its economic importance and Kyoto, seat of the imperial family, still maintains its high tradition of culture. In addition, local lords strive to develop sciences and arts in the provinces, and especially in the cities where they reside.

The aristocratic elite and the emperor, as well as the big bourgeoisie of Kyoto support and participate in a set of achievements (including those of Tawaraya Sōtatsu and Hon’ami Kōetsu) strongly impregnated with a desire for high culture, where the HEIAN period and the start of the Kamakura era serve as references. In this they are radically distinguished from the productions commanded by the new war elites which have been competing for centuries [ first ] .

Tawaraya sotatsu. Waves in Matsushima . Two paravents with 6 leaves. Ink, colors, silver and gold / paper, 2 x (166 × 370 cm )

|

Waves in Matsushima . Two paravents with 6 leaves. 1628 [ 2 ] . Ink, colors, silver and gold / paper, 2 x (166 × 370 cm ). Freer Gallery of Art

|

This artist remains an enigma: we keep very few allusions to his work, his orders and the judgments of his contemporaries. If we sit down at the start of XVII It is century, nothing is known, neither of his dates of birth and death, nor even of the location of his grave [ 3 ] .

Before 1615 [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

The painter who signed, from 1616, by the name of Sōtatsu seems to have been named “of Tawaraya” before, and “Tawaraya” would be the name of his workshop or the workshop in which he works [ 4 ] . The known activities of this type of decoration workshop, in Kyoto, bring together all the disciplines related to painting: illumination, painting on fan, lanterns, shells and paravents, architectural drawing, textile drawing, dolls. They were not only turned to the public but also to the emperor, his court and the aristocracy. Their flourishing activity meets the demand of an urban population which revives prosperity, during reconstruction which follows the long eras of wars and destruction.

Sōtatsu probably directed the Tawaraya workshop. He realizes, or had many fans produced. There are still many paintings on fan paper (Simenga) , gathered on Paravents, “Sōtatsu style”, which take up the same themes and the same compositions, where we distinguish the touch from the master and his disciples. It therefore seems that the decorative style of the Tawaraya house is very popular at the time, and that it is also there that the originality of Sōtatsu is appreciated [ 6 ] .

The Tawaraya workshop provided the emperor and his courtyard decorated papers for calligraphy. In this workshop, as Tawaraya, Sōtatsu also painted fans, before receiving larger orders, such as the restoration of an old collection of poems from the Heian era, vehicle , composed in Japanese and not in classic Chinese, as were the thirst . This era appeared, both in the emperor and his court, as a golden age of Japanese culture, at the height of the power of the emperor. This beautiful era, from their point of view, each made it revive by poems, put into speech, perhaps in music, but above all, for us, in inspired calligraphies, on decorated and chosen or chosen or made by the workshop Tawaraya in accordance with the poetry they had to receive.

Sōtatsu also relives painting from the Heian era, or YAMATO-E , by bringing his innovative mind and surprising processes there. Indeed, in 1602 the name of Sōtatsu appeared for the restoration of a collection of old sutras [ 7 ] . It is an offering deposited by the Heike family in 1164, at the end of the era of Heian (at XI It is And XII It is centuries) in the sanctuary of Itsukushima on the island of the same name (or Miyajima). The artistic creations of the Heian era, and the very particular style of the illuminations of this collection, will have an essential importance for Sōtatsu [ 8 ] And then for the whole Rinpa school to which he gives the initial impulse with, even if the beginning of the time of Kamakura (1185-1333), which follows the era of Heian, also serves as a reference [ 9 ] .

Many rollers and albums (the oldest of which dates back to 1606) where the very beautiful calligraphy of Kōetsu comes to register on leaves richly endowed with motifs with gold and silver wash by Sōtatsu, are collective works that evoke the harmony of drawing, calligraphy and poetry of the Heian era [ ten ] . Until this time gold and silver were only used to enhance a decoration of painted traces, Sōtatsu employs them in washing as shimmering effects [ 11 ] .

-

TSURU EMAKI . Anthology of poetry and flight cranes. Calligraphy: Kōetsu, Painting: Sōtatsu. Kyoto National Museum

-

Deer (retail). Calligraphy: Kōetsu, Painting: Sōtatsu. Horizontal roller. Ink of gold and silver on paper. H 34 cm. MOA Museum of Art, Atami.

-

Poem of the collection of vehicle : Chef’s Wakakashū. Feuille d’Album, 18.3 × 16.3 cm . Ink and gold on paper. Calligraphy: Kōetsu, Painting: Sōtatsu. Minneapolis Institute of Art

-

Twelve poems from SHIN KOKIN WAKASHū . Calligraphy: Kōetsu, Painting: Sōtatsu. Around 1620. Roll, ink and gold on silk, 34 × 488 cm . Of

-

POEMS AND DAMS , retail. Kōetsu calligraphy, ink; Sōtatsu painting, gold and silver wash; paper. H 34 cm , shttail. Museum the art moa.

In 1615, the shōgun Ieyasu gave land to Kōetsu in the village of Takagamine, northwest of Kyoto, and a number of craftsmen joined him [ twelfth ] . But Sōtatsu remains in Kyoto. Their collaboration then ends.

Cultural characteristics of the Heian era [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

At that time of Heian Japan emancipates, little by little, from its relationship to China to engage in an original path [ 14 ] . Although Chinese remains the official language of the Imperial Court of the Heian period, the introduction of Kana promotes the development of Japanese literature. These are the first novels in world literature, as The said of the genji ( XI It is century), and poems vehicle , all written in Japanese characters and not in classic Chinese.

Ancient literature thus married happily, narrative content and poetic expression to dexterity in the handling of the brush for calligraphy in Japanese syllabaries not at all And to powers evocative of colors, forms identifiable by their relationship with the text, and of the more or less luminous beauty of the metallic effects of gold and silver: the meaning and its evocative power emerging from all these elements in echoes with each other.

Yamato-e painting, practiced in the Heian era, employs codes that also stand out for Chinese painting, in particular for the representation of interior scenes, depending on the roofs removed FUKINUKI YATAI , and in the stylization of bodies in court clothes, men and women. It is these paintings that illuminate the texts of the novels, on the Emaki , and poems, or tales, such as ISE tales [ 15 ] , on separate leaves. The Tawaraya workshop probably produced these separate, square, shikishii , or oblong, tanzaku . During the Keichō era (11596-1615) the workshop will have developed above all the process for decorating papers by printing wood engravings.

After 1615 [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

It is around this date that Sōtatsu is recognized as a talented artist. We keep from him very different paintings from the first, larger, more colorful. Indeed he seems to no longer be able to collaborate with Kōetsu, and many figurative paintings, most often on Paravent, characterize this new era of his life as an artist.

-

![Lions chinois. 2 de 6 fusuma. Vers 1620[16]. Couleurs sur cèdre, ch. H. 182 ; L. 125 cm. Yōgen-in, Kyōto](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/cc/Tawaraya_S%C5%8Dtatsu-%E4%BF%B5%E5%B1%8B%E5%AE%97%E8%BE%BE-%E4%BA%AC%E9%83%BD%E5%85%BB%E6%BA%90%E9%99%A2.jpg/183px-Tawaraya_S%C5%8Dtatsu-%E4%BF%B5%E5%B1%8B%E5%AE%97%E8%BE%BE-%E4%BA%AC%E9%83%BD%E5%85%BB%E6%BA%90%E9%99%A2.jpg)

Chinese lions . 2 of 6 fusuma . Around 1620 [ 16 ] . Colors on cedar, ch. H. 182; L. 125 cm . Yōgen-in, kyōto

-

![Les dieux du vent et du tonnerre. Tawaraya Sōtatsu. Paire de paravents à deux panneaux, non signés. Encre et couleurs sur fond d'or, sur papier. Vers 1626[17]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/af/Wind-God-Fujin-and-Thunder-God-Raijin-by-Tawaraya-Sotatsu.png/200px-Wind-God-Fujin-and-Thunder-God-Raijin-by-Tawaraya-Sotatsu.png)

Wind and thunder gods . Tawaraya Sōtatsu. Pair of two panels, not signed. Ink and colors on a gold background, on paper. Around 1626 [ 17 ]

-

Eight chapters of the said of Gengi. Sōtatsu. Ink, color and gold on golden paper. 8 -sheet screen, 81 × 327 cm . Met. Each screen 154.5 × 169.8 cm Kennin-Ji, KyōTo

-

Black and maple pines . 6 -leaf screen, l 3.62; H 1.51 m. Yamataane Museum of Art. Technique of TARASHIKOMI On the pine trunks.

-

“Mont utsu”, from Tales de Ise ( ISE Monogatari ), around 1634. Poetry sheet ( shikishii ), climb in suspended roller, image: 24.6; 20.8 cm. Calligraphy Toshiharu (1611–1647), painting: Sōtatsu. Put

-

![Danseurs de bugaku. Vers 1626[18]. Paire de paravents à deux panneaux. Encre, couleurs, or / papier. 169 x 165 cm. Daigo-ji, Kyoto](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e9/S%C3%B4tatsu_Bugaku_links.jpg/146px-S%C3%B4tatsu_Bugaku_links.jpg)

Bugaku dancers . Around 1626 [ 18 ] . Pair of two panels. Ink, colors, gold / paper. 169 x 165 cm. Daigo-ji, Kyoto

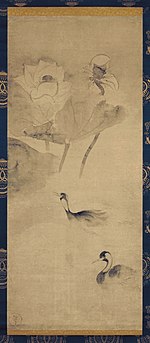

“Sōtatsu endeavors to make the flexibility of the lines as well as the vigor of the accents and succeeds in qualifying the united surfaces by the technique TARASHIKOMI (Freshly placed ink keys which, by spraying water, become degraded spots). He later resumes, these processes in his monochrome paintings in Chinese ink, introducing in the art of washing a new decorative feeling, far from the Chinese tradition and in its rollers and paravents in superimposed colors to form unexpected harmonies . He also innovates [see his monochrome paintings: Ducks on the Lotus pond ] in the treatment of reasons without circle, according to the ancient Chinese party said boneless . » [ 19 ] .

He produced, in particular, during this period, a large number of ink and colors paravents, on a gold background.

His big decorative screening is, for the most part, signed “Hokkyō sōtatsu” next to a round cachet [ 20 ] . “This title of Howskyo is a high priestly dignity generally granted to outstanding artists ” [ 21 ] . According to Miyko Murase and others, not mentioned by Okudaira Shunroku [ 16 ] , this distinction would have followed the reconstruction of the Yōgen-in temple, in Kyoto [ 22 ] , in 1621, in which Sōtatsu participated with the paintings of the doors (painted on both sides: white elephants and rhinos and, on the back, figures of fantastic animals) and paintings of sliding partitions with large pines and rocks. Okudaira Shunroku suggests that these paintings were made before 1624. This approximate dating is one of the very rare benchmarks generally accepted.

On the doors of Yōgen-in, the two rhinos and the four fantastic animals, all, extraordinary, are protective beings, some against the dangers of water (rhinoceros) and against the dangers of fire ( Sangei ); Welcome to the temples exposed to these two permanent risks. These animals are usually treated in a much more conventional and more static way, while here they appear in a completely free, original and rapid execution. Pins and rocks, for their part, seem to recall Chinese landscapes in blue and green; The trunks are all spotted, according to a process which will become the TARASHIKOMI , by water spot on the paint becoming degraded spots.

Style: few deployed means, variations in the pattern [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

The pair of paravents, in large format, to the poems of “La Sente aux Lierres” is quite remarkable. The two paravents, placed next to each other, make up a space in continuity. He evokes a path, the one that the reader of the poems travels (the “path” could refer to time, time being, at least, one of the motifs of the first calligraphic poem). The painter uses extremely few means, but they are of perfect poetic efficiency. The ivy, so many patterns playing on subtle variations, which hang from top to bottom come to echo the calligraphies, as if the sight of these leaves, encountered by the traveler mentioned poems. Reading the first poem, in fact, two poems meet, one, visible, the other, absent. Because the calligraphic poem refers to another, drawn from Inside d’Ise , which, both, recall the memory of a lack, the lack of the beloved (e). And if the two paravents, as if to isolate people in space, were arranged in a circle, they would form “a kind of ribbon of Möbius: the path then becomes the sky, then the sky is going on” [ 23 ] .

If in this example the few deployed means is particularly striking, it is not a unique case. Compared to the other painters of his time who deploy a multitude of patterns, great effects, Sōtatsu makes it less. One could say that it applies, all kept proportions, the principle of widespread economy in a part of the art of XX It is century : ” less is more » [ 24 ] . This reduction in means – few reasons, some large forms, all articulated with the vertical regularity of calligraphies when they are present – is what best characterizes the work of Tawaraya Sōtatsu, knowing that he was addressing in Japan cultivated, imbued with subtle literary references.

- I see dawn pale .

- O ducks-mandarins passing ,

- Do you give me a message from my loved one?

(Man’yōshū, XI, 2491 — VIII It is century)

“Sōtatsu is hardly customary with such discretion. This extremely famous wash is to tell the truth very little representative in its way, usually infinitely more bypass and colorful. In the pallor of the half-day, the two ducks teasing by a caressing, playful brush can be said, sail on water that merges with the mist of dawn … (…) [ 25 ] ».

The taste for decor, which is the mark of the time, brings artists back to the aristocratic novels of formerly, pretexts for resolutely colorful evocations, to sumptuous tissue deployments. Here, a famous scene of the ISE MONOGATARI 6

Textually:

- “A man had loved a woman infinitely for a long time.

- But he couldn’t have him for himself alone.

- He managed to remove it and fled with her in the dark night (…).

- The night was advanced, thunder rumbled, the rain fell violently.

- The man brought the woman into a ruined barn, ignoring that there were demons.

- With his ready arc, his quiver on the shoulder, he held guard at the entrance, waiting for dawn.

- Meanwhile, a demon swallowed the lady: Stupid!

- She was crying: Anaya ! which was lost in the crash of lightning.

- When he did day, the man went to find the woman. In his place, nothing! ” [ 26 ] .

- Atami (museum the art moa):

- Deer roll , run in length, ink of gold and silver on paper.

- Cleveland (Mus. of Art):

- The priest Zen Méka , high roll, ink on paper.

- ISHIKAWA (YAMAKAWA FOUNDATION OF ART):

- Maki , six -sheet screen, color on paper.

- Kyōto (Museum National The Kyoto):

- Ducks on the Lotus pond , ink on paper (50×116 centimeters), poem by Man’yōshū.

- Water game in the lotus pond , high roll, ink on paper, in the register of national treasures.

- Herbs and flowers , colors on gold paper, four sliding doors.

- Herbs and flowers , colors on gold paper, four sliding doors, Inen stamp.

- Dragon Roll in height, ink on paper.

- Kyōto (temple roku-in):

- Oxen , two rolls in height, ink on paper, inscription of Karasumaru Mitsuhiro, in the register of important cultural goods.

- KyōTo (Temple Daigo-Ji):

- Bugaku , colors on golden paper, two two -leaf paravents, in the register of important cultural goods.

- Paravents with eleven fans , colors on golden paper, two two -leaf paravents.

- Ducks in the reeds , ink on paper, two screens.

- Kyoto (Temple Kennin-Ji):

- The gods of thunder and wind , colors on golden paper, two two -leaf paravents, in the register of important cultural goods.

- Kyoto (Temple Myoho-in):

- Maple , colors on gold paper, range.

- Kyoto (Temple Yōgen-in):

- Pins and rocks , colors on gold paper, twelve sliding doors.

- Imaginary animals , colors on wood, four sliding doors, in the register of important cultural goods.

- NARA (Musée Yamato Bunkakan):

- Scene of Ise Monogatari , ink and colors on paper (21.1×24.7 centimeters).

- Tōkyō (Nat. Mus.):

- Cherry trees and Yamabuki (Kerries of Japan) , colors on paper, two six -leaf paravents, allocation.

- Plants of the four seasons in bloom , colors on paper, two six -leaf paravents, Inen stamp.

- Dragon , high roll, ink on paper.

- For the intersection (coat of arms , high roll, light colors on paper.

- Tōkyō (Museum Goto):

- The thousand cranes , two shikishi, ink of gold and silver on paper.

- TOKYO (HATAKEYAMA Kinenka Mus.):

- Flowers and herbs of the four seasons , length roll, ink of gold and silver on paper, by Sōtatsu and Kōetsu.

- Water game in the lotus pond , high roll, ink on paper.

- Tokyo (Imperial Household Agency) :

- Paravents with forty-eight fans , colors on paper, two six -leaf paravents, Inen stamp.

- Sheet , high roll, ink on paper.

- Tokyo (Okura Cultural Foundation):

- Floating fans , color on paper, two six -leaf paravents, Inen stamp, in the register of important cultural goods.

- Tokyo (Seikadō Foundation):

- Episode Sekiya and Miotsukushi episode from Genji Monogatari , golden paper colors, two six -leaf paravents, in the register of important cultural goods.

- TOKYO (YAMATANE ART MUS.):

- Maki, Chinese and maple pines , colors on gold paper, six -leaf screen, Taiseiken stamp.

- Washington DC (Freer Gallery of Art):

- Matsushima , colors on paper, two six -leaf paravents.

Bibliography [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

- Manuela Moscatello ( you. ) et al. (Exhibition presented at the Cernuscchi museum from October 26, 2018 to January 27, 2019), Kyoto treasures: three centuries of Rinpa creation , Paris, museum meeruses, , 191 p. , 30 cm. (ISBN 978-2-7596-0399-2 )

- Christine Guth, Japanese art of the Edo period , Flammarion, coll. “All art”, , 175 p. , 21 cm. (ISBN 2-08-012280-0 )

- MIYEKO MURASE ( trad. from English), Japan art , Paris, LGF editions – Pocket Book, coll. “The Pochotheque”, , 414 p. , 19 cm. (ISBN 2-253-13054-0 ) , p. 248-275

- Christine Schimizu, Japanese art , Paris, Flammarion, coll. “Old art funds”, , 495 p. , 28 x 24 x 3 cm env. (ISBN 2-08-012251-7 ) , And Christine Schimizu, Japanese art , Paris, Flammarion, coll. “All art, history”, , 448 p. , 21 x 18 x 2 cm env. (ISBN 2-08-013701-8 )

- Bénézit dictionary, Dictionary of painters, sculptors, designers and engravers , vol. 13, Gründ editions, , 13440 p. (ISBN 2-7000-3023-0 ) , p. 48, 49 .

- Akiyama Terukazu, Japanese painting – Asia’s treasures , Éditions Albert Skira – Geneva, , 217 p. , p. 102, 141, 145/153, 156, 177

- Maurice Coyaud, The Empire of the Look – a thousand years of Japanese painting , Paris, Phebus editions, Paris, , 256 p. (ISBN 2-85940-039-7 ) , p. 32, 33, 56, 166, 167, 168, 170, 171

Related articles [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

Notes and references [ modifier | Modifier and code ]

- However, the generals Oda Nobunaga and Tokugawa Ieyasu, who takes power as the first Shogun Tokugawa and founded this period of Edo, maintain relations with Hon’ami Kōetsu as an expert in sabers. Myeko Murase, 1996, p. 252

- “1628, or shortly after”. Okudaira shunroku in Manuela Moscatielo (dir.), 2018, p. 27

- Okudaira shunroku in Manuela Moscatielo (dir.), 2018, p. 18-23

- Okudaira shunroku in Manuela Moscatielo (dir.), 2018, p. 18-23, including 21: “Tawaraya painter”

- freersackler.si.edu : maximum magnification possible.

- Okudaira shunroku in Manuela Moscatielo (dir.), 2018, p. 19

- Manuela Muscatello (DIR.), 2018, p. 18-23

- Okudaira shunroku in Manuela Moscatielo (dir.), 2018, p. 19-20

- Fukui Masumi in Manuela Moscatielo (dir.), 2018, p. 62

- See : Roll of deer poems. v. 1610. Seattle Asian Art Museum .

- Christine Shimizu, 1997, p. 339

- MIYEKO MURASE, 1996, p. 258. In this regard, Christine Shimizu brings this date of the siege of Osaka (1614-1615) closer to the date of the siege (1614-1615) after which Ieyasu Tokugawa, previously very close to the Suruta Oribe tea master, accuses him of betrayal and forces him to suicide. This could be the reason for the sidelining of Kōetsu, also very close to the tea master. Christine Shimizu, 1997, p. 338

- Okudaira shunroku in Manuela Moscatielo (dir.), 2018, p. 27

- Pierre François Souyri, New History of Japan , Paris, Perrin, , 627 p. , 24 cm (ISBN 978-2-262-02246-4 ) , p. 173

- Fukui Masumi in Manuela Moscatielo (dir.), 2018, p. 70

- Okudaira shunroku in Manuela Moscatielo (dir.), 2018, p. 23

- Okudaira shunroku in Manuela Moscatielo (dir.), 2018, p. seventy three

- Okudaira shunroku in Manuela Moscatielo (dir.), 2018, p. 78-79

- Dictionary Bénézit, vol. 13, 1999, p. 48-49

- Akiyama Terukazu 1961, p. 145

- MIYEKO MURASE, 1996, p. 259

- Yōgen-in is a private temple, originally, dedicated to the memory of the Asai clan. : Okudaira shunroku in Manuela Moscatielo (dir.), 2018, p. 22

- Okudaira shunroku in Manuela Moscatielo (dir.), 2018, p. 83

- See, from the use of this expression by its creator, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, its involvement in modern architecture, design and plastic arts in XX It is century.

- Maurice Coyaud 1981, p. 166-167

- Maurice Coyaud 1981, p. 170-171

Recent Comments