Birmingham (Alabama) – Wikipedia

| Birmingham city |

|

|---|---|

| City of Birmingham | |

|

|

View of the Urban Landscape of Birmingham from Vulcan Park |

|

| Location | |

| State | |

| Federated state | |

| County | Jefferson Shelby |

| Administration | |

| Mayor | Randall Woodfin (D) |

| Territory | |

| Coordinate | 33°31′03″N 86 ° 48′34 ″ in / 33.5175°N 86.809444°W |

| Altitude | 187 m s.l.m. |

| Surface | 384,9 km² |

| Inhabitants | 209 880 (2018) |

| Density | 545,28 Ab./km2 |

| More information | |

| Code. mail | 35201-35224, 35226, 35228-35229, 35231-35238, 35242-35244, 35246, 35249, 35253-35255, 35259-35261, 35266, 35270, 35282-35283, 35285, 35287, 35288, 35290-3529888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888888 |

| Prefix | 205 |

| Jet lag | UTC-6 |

| Nickname | “The Magic City”, “Pittsburgh of the South” |

| Mapping | |

|

|

| Institutional site | |

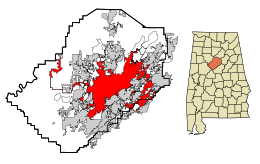

Birmingham ( /ˈBɜːrmɪŋhæm/ bur-ming-ham ) is a municipality ( city ) of the United States of America which is located between the counties of Jefferson (of which it is the capital) and Shelby, in the state of Alabama. The population was 209,880 people at the 2018 census, which makes it the most populous city of the state and the hundredth most populous city of the nation. It is the main city of the metropolitan area known as Greater Birmingham.

According to the United States Census Bureau, it has a total area of 151.9 square miles (393 km²), consisting of 149.9 square miles (388 km²) of land and 2.0 square miles (5.2 km²) of water .

Climate [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

The highest temperature ever recorded was 107 ° F (42 ° C), on July 29, 1930, [first] While the lowest temperature ever recorded was −10 ° F (−23 ° C), on February 13, 1899. [2]

| Birmingham [3] [4] [5] [6] [7] | Months | Seasons | Year | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Feb | Mar | Apr | Mag | Gulp | Lug | Ago | Set | There | Nov | Dic | Inv | At | East | Or | ||

| T. max. media (°C) | 12.1 | 14.7 | 19.3 | 23.6 | 27.5 | 30.9 | 32.7 | 32.6 | 29.5 | 24.1 | 18.6 | 13.3 | 13.4 | 23.5 | 32.1 | 24.1 | 23.2 |

| T. min. media (°C) | first | 2.8 | 6.5 | 10.3 | 15.4 | 19.8 | 21.9 | 21.6 | 17.9 | 11.6 | 6.4 | 2.4 | 2.1 | 10.7 | 21.1 | 12.0 | 11.5 |

| Rainfall (mm) | 122.9 | 115.1 | 132.8 | 111.3 | 126.7 | 111.3 | 121.9 | 99.8 | 99.1 | 87.4 | 123.2 | 113.0 | 351.0 | 370.8 | 333.0 | 309.7 | 1 364.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 70.5 | 66.5 | 64.2 | 65.0 | 70.1 | 71.6 | 74.4 | 74.6 | 74.0 | 71.6 | 71.4 | 71.2 | 69.4 | 66.4 | 73.5 | 72.3 | 70.4 |

Birmingham was founded on June 1, 1871, at the end of the American civil war, as an industrial area. It was so called in honor of Birmingham, the main industrial city of the United Kingdom. The city arose in a valley where a large amount of iron had been detected, useful in the production of steel. The growth of the city was initially slowed down by a violent cholera epidemic and the crash of the Wall Street bag of 1873.

In the early 1900s, the city center suffered a showy residence, and became a rich residential area with new neoclassical -style houses. Between 1902 and 1912 four skyscrapers were then built at the intersection of 20th Street and the 1st Avenue North. These skyscrapers took the name of the “heaviest corner on earth”.

In 1916 the city was affected by an earthquake, which went down in history as “Irondale earthquake” (magnitude 5.1) and some buildings were conspicuously damaged.

The “great depression” of the 1930s hit Birmingham in a particularly hard way, and saw the closure of many industries and the migration of hundreds of peasants, who came from the country to the city in search of work. Subsequently, in the early 1940s, the enormous demand for steel following the II World War, had the city of Birmingham prosper again.

Over the years, an African American middle class developed over the years, which however remained segregated until the period of the struggles for civil rights in the sixties.

In the middle of the twentieth century Birmingham had become one of the most important industrial centers in the United States so much so that the nicknames of Magic City It is Pittsburgh del barrel . The most important industries in the city were those of iron and steel, then over the years, while the industry began to get into crisis throughout the nation, the city economy diversified also focusing on medical research, banks and on publishing.

In recent years, the sectors of biotechnology and computer technology and Birmingham have grown rapidly has been declared as one of the best US cities in which to live [8] .

Between 1950 and 1960 the city of Birmingham jumped to the honors of national and international news as one of the main seats of the Movement of Civil Rights. At that time, most of the African Americans residing in the city worked in the mines and in the steel industries.

In the 1950s, many African American were affected by Ku Klux Klan after this had managed to get in possession of numerous cartons of dynamite kept in the iron extraction mines. In fact, many citizens of white breed were not in favor of the social changes proposed by the movement of civil rights and many homes of African Americans were affected in those years by the explosion of these devices. Many color workers, in order to protect their families, were forced to move to the outskirts of the city. These dynamite events assigned the nickname “to the city of Birmingham Bombingham “.

Locally the movement of civil rights was led by Fred Shuttlesworth, a proud preacher who became legendary for his courage in the face of threats and violence.

The watershed inside the Birmingham movement took place in 1963, when Fred Shuttlesworth asked Martin Luther King to come to Birmingham to help him put an end to violence and racial segregation. Martin Luther King welcomed the request and went to Birmingham as a shepherd and remained for the first years of his preacher career [9] .

Together they launched the so -called “project C” (where “c” was for “confrontation”), an imposing and non -violent demonstration against the abuses perpetrated by whites. In 1963 Martin Luther King was imprisoned for taking part in a non -violent event and while he was in prison he wrote the famous “letter from the prison of Birmingham”, a sort of treaty in which he explained the causes of racial segregation in the United States . Immediately after King’s arrest, many and noisy protests were raised in the city, which were violently repressed by the police with tear gas and lightening charges. Following the protests more than 3,000 people were arrested, including many minors.

On a Sunday morning of September 1963 an artisan bomb exploded in the Battista church of the 16th road killing four color girls [ten] . The subsequent protests of the movement activists, together with a growing indignation of public opinion against the police and Ku Klux Klan, contributed to the change of course against African American citizens and to the definitive approval in 1964 of the Civil Right Act.

Civil architectures [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

Birmingham is home to 66 Torre houses. [11]

Birmingham is also the cultural and artistic capital of Alabama, with numerous art galleries within the city, including the Birmingham Museum of Arts.

Birmingham is also home to the most important orchestras and dance companies in the Alabama state.

Museums [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

In Birmingham there are many museums. The largest of all is the Birmingham Museum of Arts.

Inside the Kelly Ingram Park there is also the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, which offers a narrative path for memorabilia and images on the story of the racial persecutions that occurred in the city.

The Southern Museum of Flight, on the 73th Street North, is a civil museum dedicated to aviation. Inside the structure there are about 100 planes, as well as original engines, models and vintage photographs. In addition, the museum is the headquarters of the Alabama Aviation Hall of Fame, which tells the story of the aviation of Alabama through some collective biographies. In the city there is also a museum of motorcycles, the Barber Vintage Motorsports Museum

Inhabitants surveyed (in thousands) [twelfth] [13] [14] [15]

Demographic evolution [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

According to the census [16] of 2010, there were 212 237 people.

The latest 2018 data speak of 209 880 inhabitants.

Foreign ethnic groups and minorities [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

According to the 2010 census, the city’s ethnic composition was made up of 73.4% of Bianchi, 22.3% of African Americans, 0.2% of Native American, 1.0% of Asian, 2, 2, 1% of other ethnic groups, and 1.0% of two or more ethnic groups. Hispanic or Latinos of any ethnicity were 3.6% of the population.

In 2014 the major public companies of Birmingham by share capitalization were Regions Bank (14.61 billion dollars), Vulcan Materials (8.45 billion dollars), Energegen (6.47 billion dollars), Protective Life (5.47 billions of dollars) and Healthsouth (3.15 billion dollars). [17]

In 2015 the major private companies of Birmingham for annual turnover and number of employees were: O’Neal Steel (2.66 billion dollars, 550 employees), Ebsco Industries (2.5 billion dollars, 1 220 employees), Drummond Co , Inc. (2.4 billion dollars, $ 1 380), Brasfield & Gorrie, LLC (2.2 billion dollars, 973 employees) and McWane Inc. (1.7 billion dollars, 620 employees). [18]

The city is served by Birmingham-Shuttlesworth international airport.

Twinning [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

Birmingham is twinned with: [19] [20]

Hitachi, Dal 1982;

Hitachi, Dal 1982;  Székesfehérvár, Dala 1995;

Székesfehérvár, Dala 1995;  AnShan, Dal 1996;

AnShan, Dal 1996;  Geweru, Dal 1997;

Geweru, Dal 1997;  Pomigliano d’Arco, since 1998;

Pomigliano d’Arco, since 1998;  Chaoyang district, since 1998;

Chaoyang district, since 1998;  Maebashi, dal 1998;

Maebashi, dal 1998;  Krasnodon, dal 1999;

Krasnodon, dal 1999;  Vinnycja, Dal 2003;

Vinnycja, Dal 2003;  Department of Guédiawaye, since 2005;

Department of Guédiawaye, since 2005;  Plzeň, Dal 2005;

Plzeň, Dal 2005;  Rosh HaAyin, dal 2005;

Rosh HaAyin, dal 2005;  Al-Karak, Dal 2005;

Al-Karak, Dal 2005;  Winneba, dal 2009;

Winneba, dal 2009;  Liverpool, dal 2015

Liverpool, dal 2015  Kingston, dal 2017

Kingston, dal 2017

- The folk song Down in the Valley , also known as Birmingham Jail , contains the verse: “Write me a letter, Send It by Mail; Send It in Care of the Birmingham Jail” (‘Write me a letter, Mandala by mail; direct it to the prison of Birmingham’).

- The song Sweet Home Alabama Of the Lynyrd Skynyrd contains the verse “In Birmingham they love the governor” (” A Birmingham love the governor ‘).

- The song Black Betty Contains the verse “She’s from Birmingham (Bam-Ba-Lam) Way Down in Alabam ‘(Bam-Ba-Lam)” (‘ She is from Birmingham, down in Alabama ‘).

- Randy Newman wrote a song entitled Birmingham , contained in the album Good Old Boys (1974).

- ^ July Daily Averages for Birmingham, AL (35209) . are Weather.com . URL consulted on November 24, 2011 (archived by URL Original on 27 October 2012) .

- ^ February Daily Averages for Birmingham, AL (35209) . are Weather.com . URL consulted on April 21, 2014 (archived by URL Original June 28, 2014) .

- ^ Station Name: AL BIRMINGHAM AP ( TXT ), are ftp.ncdc.noaa.gov , National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. URL consulted on April 21, 2014 (archived by URL Original July 16, 2020) .

- ^ NowData – NOAA Online Weather Data . are nws.noaa.gov , National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. URL consulted on December 2, 2016 .

- ^ WMO Climate Normals for BIRMINGHAM/WSFO AL 1961–1990 ( TXT ), are ftp.atdd.noaa.gov , National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. URL consulted on April 21, 2014 .

- ^ WMO Climate Normals for BIRMINGHAM/MUNICIPAL ARPT AL 1961–1990 ( TXT ), are ftp.atdd.noaa.gov , National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. URL consulted on April 21, 2014 .

- ^ Average Weather for Birmingham, AL – Temperature and Precipitation . are Weather.com , The Weather Channel, dicembre 2011. URL consulted on September 20, 2011 (archived by URL Original on 27 October 2012) .

- ^ ( IN ) America’s Most Livable Communities [ interrupted connection ] . are Mostlivable.org . URL consulted on June 10, 2010 .

- ^ americanheritage.com , http://www.americanheritage.com/articles/magazine/ah/2010/4/2010_4_90.shtml .

- ^ The city of fear . are Crimelibrary.com (archived by URL Original on August 18, 2007) .

- ^ Tall Buildings of Birmingham . are Emporis.com . URL consulted on February 8, 2015 .

- ^ Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015 . are Census.gov . URL consulted on July 2, 2016 .

- ^ U.S. Decennial Census . are census.gov . URL consulted on May 27, 2013 (archived by URL Original May 12, 2015) .

- ^ Population Estimates . are census.gov , United States Census Bureau. URL consulted on May 20, 2016 .

- ^ U.S. Census Bureau

- ^ American FactFinder . are factfinder2.census.gov , United States Census Bureau. URL consulted on March 14, 2017 .

- ^ Ranking Alabama’s largest public companies – Birmingham Business Journal . are Birmingham Business Journal , June 27, 2014. URL consulted on July 21, 2015 .

- ^ The Birmingham 25: Meet the Magic City’s largest private companies . are Birmingham Business Journal , June 16, 2015. URL consulted on July 21, 2015 .

- ^ Birmingham Sister Cities Commission . are Birminghamsisteracits.com , July 16, 2016. URL consulted on January 7, 2017 (archived by URL Original March 2, 2017) .

- ^ ( HU ) Agnes Bozsoki, List of Partner Cities Partner and sister cities list [ Partner and Twin Cities List ] . are City of Szekesfehervar . URL consulted on 5 August 2013 (archived by URL Original December 8, 2012) .

- Saffold Berney, Birmingham , in Handbook of Alabama , Mobile, Mobile Register print., 1878.

- City Directory of Birmingham , Atlanta, Ga., Interstate Directory Co., 1884.

- John W. DuBose, ed., The Mineral Wealth of Alabama and Birmingham (Birmingham, 1886)

- 1887 Pocket Business Directory and Guide to Birmingham, Ala. [ interrupted connection ] , 1887. Hosted on Birmingham Public Library.

- Jefferson County and Birmingham, Alabama: Historical and Biographical , Teeple & Smith, 1887, ISBN 978-0-89308-041-9.

- Henry M. Caldwell, History of the Elyton Land Company and Birmingham, Ala. 1892.

- Code of City of Birmingham, Alabama. 1917.

- Birmingham , in Automobile Blue Book , USA, 1919.

- Cruikshank, A History of Birmingham and Its Environs (2 vols., Chicago, 1920)

- Thomas McAdory Owen, Birmingham , in History of Alabama and Dictionary of Alabama Biography , Chicago, S.J. Clarke, 1921, OCLC 1872130 .

- Harrison A. Trexler, “Birmingham’s Struggle with Commission Government,” National Municipal Review, XIV (November 1925)

- George R. Leighton, “Birmingham, Alabama: The City of Perpetual Promise,” Harper’s Magazine, CLXXV (August 1937)

- Federal Writers’ Project, Birmingham , in Alabama; a Guide to the Deep South , American Guide Series, New York, Hastings House, 1975.

- Florence H. W. Moss, Building Birmingham and Jefferson County (Birmingham, Ala.: Birmingham Printing Company, 1947)

- John C. Henley, Jr., This Is Birmingham: The Story of the Founding and Growth of an American City. 1960.

- Paul B. Worthman, “Black Workers and Labor Unions in Birmingham, Alabama, 1897-1904,” Labor History, 10 (Summer 1969)

- Paul B. Worthman, “Working Class Mobility in Birmingham, Alabama, 1880-1914,” in Anonymous Americans: Explorations in Nineteenth-Century Social History, ed. Tamara K. Hareven (Englewood Cliffs, 1971)

- Blaine A. Brownell, Birmingham, Alabama: New South City in the 1920s , in Journal of Southern History , vol. 38, 1972, JSTOR 2206652 .

- McMillan, Malcolm C. Yesterday’s Birmingham. Miami: E.A. Seeman Publishing, 1975.

- Oryai Maazi and Agalea (for the), Birmingham, AL , in Encyclopedia of American Cities , New York, E.P. Dutton, 1980, OL 4120668M .

- Robert P. Ingalls, Antiradical Violence in Birmingham During the 1930s , in Journal of Southern History , vol. 47, 1981, JSTOR 2207401 .

- Valley and the Hills: An Illustrated History of Birmingham and Jefferson County. 1981

- Robert J. Norrell, Caste in Steel: Jim Crow Careers in Birmingham, Alabama , in Journal of American History , vol. 73, 1986, JSTOR 1902982 .

- Old Birmingham , OCLC 38508791 . 1991-

- George thomas kuran, Birmingham, Alabama , in World Encyclopedia of Cities , 1: North America, Santa Barbara, Calif., ABC-Clio, 1994. Hosted on Open Library.

- Henry M. McKiven, Iron and Steel: Class, Race, and Community in Birmingham, Alabama, 1875-1920 , Univ of North Carolina Press, 1995, ISBN 978-0-8078-4524-0.

- Alan Draper, New Southern Labor History Revisited: The Success of the Mine, Mill and Smelter Workers Union in Birmingham, 1934-1938 , in Journal of Southern History , vol. 62, 1996, JSTOR 2211207 .

- The South: Alabama: Birmingham , in deer , Let’s Go, New York, St. Martin’s Press, 2008, OL 24937240m .

- Lynne B. Feldman, A Sense of Place: Birmingham’s Black Middle Class Community, 1890-1930 (Tuscaloosa, 1999)

- Alabama: Birmingham , in Louisiana & the Deep South , Lonely Planet, 2001. Ospitato su Open Library.

- American Association for State and Local History, Alabama: Birmingham , in Directory of Historical Organizations in the United States and Canada , 15th, 2002, ISBN 0-7591-0002-0.

- Richard Pillsbury (the care of), Birmingham , in Geography , New Encyclopedia of Southern Culture , vol. 2, University of North Carolina Press, 2006, p. 156 , OCLC 910189354 .

Recent Comments