Lingua Ebratica – Wikipedia

Child Jewish language (in Israeli Jewish: עברδ – Hebrew ) We mean both the Biblical Jewish (or classic) both the Modern Hebrew , the official language of the state of Israel and the Jewish autonomous Oblast in Russia; The modern Hebrew, grown in a social and technological context very different from the ancient one, contains many lexical elements borrowed from other languages. [first] Hebrew is a Semitic language and therefore part of the same family that also includes Arab, Aramaic, Amarica, Tigrine, Maltese and others languages. By number of locutors, Jewish is the third language of this strain after Arabic and Amarico. [2]

At 2022, it is spoken by 9.4 million total speakers [3] .

In the tanakh (תנ”ך, abbreviation of Torah, nevyim It is Khetubbim , “Law, Prophets and Writings”) The name Eber (עבר) is remembered, attributed to an ancestor of the Patriarch Abraham (Genesis 10.21 [4] ). On the same root, the word עברctor recalls several times in the Bible ( ivri , “Jew”), although the language of the Jews in the Scriptures is never said Hebrew to mean “Hebrew”. [5]

Although the most famous text written in Jewish is the Bible, the name of the language used for its editorial staff is not mentioned. However, in two steps of the Scriptures (2 kings 18.26 [6] Isaiah 36.11 [7] ), it is said of how the Messi del King Ezekia asked Ravshaqe, the envoy of the Assiro Sennacherib king, to be able to speak in the ARAM language (Aramaic, Aramit ) and not in Judea language (Jewish girl, yehudit ). This request was aimed at preventing the people, who apparently did not have to understand the first, could understand their words. It is therefore possible that the second term remembered may have been the name attributed then to the Jewish language or, at least, that of the dialect spoken in the Jerusalem area. [2] [8]

Today the language of the Bible is called “Biblical Hebrew”, “classic Hebrew” or also, in religious environments, “Holy Language”. This, in order to distinguish it from the Hebrew of Mishnah (from the scholars also called with a Jewish expression לשון חז”ל, hazal : the “language of essays”; Or “Rabbinic Hebrew”), which represents a late evolution of Hebrew in the ancient world. [2]

Biblical language [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

Originally, the Jewish one was the language used by the Jews when they still lived in the majority in the Near East. It is estimated that about two thousand years ago the Hebrew was already in disuse as a spoken language, being replaced by the Aramaic.

The books of the Jewish Bible (except some parts of the most recent books, such as Daniele’s book, written in biblical Aramaic), all the Mishnah, most of the non -canonical books and most of the manuscripts of the dead Sea were written in Jewish. The Bible was written in Biblical Hebrew, while Mishnah was drawn up in a late variety of the language, called “Jewish Mishnaic”. [2]

Only the Samaritan community did not use the Mishnaic variety, but preferred to maintain its own, called “Samaritan Jewish”. [8]

Lingua Mishnaica [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

During the period of the second temple or a little later (there is no consensus in this regard between academics), most Jews abandoned the daily use of Hebrew as a language spoken in favor of the Aramaic, which has become the international language of the Near East. A recovery of Hebrew as a spoken language was thanks to the ideological action of the Maccabees and the Asmonei, in an attempt to oppose the strong Hellenizing push of that era, and later during the Kokhba bar revolt; They were useless efforts, as Jewish was no longer understood by the mass. Hundreds of years after the period of the second temple, the Ghemarah was composed in Aramaic, as well as the Midrashim. [9]

Medieval language [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

In the following centuries the Jews of the diaspora continued to use this language only for religious ceremonies. In everyday life the Jews expressed themselves, however, in local languages or in other languages created by the Jews themselves in the diaspora, non -Semitic languages such as yiddish , The rogue , The Judaic-Romanian or the Judaic-Veneziano , born from the encounter between the expression and the Jewish alphabet and the European languages; It is very interesting, for example, a copy of a To adjace to pesach Written in Venetian in Jewish characters around the eighteenth century. [2]

Furthermore, even when the Hebrew no longer represented the spoken language, it continued to act as a generation generation, during everything that the period of medieval Hebrew is said, as the main tool of written comunication of the Jews. His status among the Jews was then analogous to that of Latin in Western Europe among Christians. This especially in issues of Halachic nature: for the drafting of the documents of the religious courts, for the collections of halakot , for comments on sacred texts etc. The drafting of letters and contracts between Jews was also often made in Hebrew; Since the women read Jewish, but did not perfectly understand it, the halachic and exegetical literature intended for them in the Ashkenazite communities was written in Yiddish (think, for example, of the Tseno Ureno text). Even the Jewish works of a non -religious or non -Halachic nature were composed in the languages of Jews or in a foreign language. [9] For example, Maimonide wrote his Mishne Torah in Hebrew, while his famous philosophical work The guide of perplexed , intended for the scholars of his time, was composed in Judeo-Arabo. However, the works of secular or worldly subject were portrayed in Hebrew, if of interest to the Jewish communities of another language, as precisely in the case of The guide of perplexed . [ten] Among the most famous families for dealing with translation from Judeo-Arabic to Hebrew during the Middle Ages were the Ibn Tibbons, a family of rabbis and translators active in Provence in the XII and XIII century. [11]

After the Talmud, several regional dialects of medieval Jewish dialects developed, among which the most important was the Jewish Tiberiense or Masoretic Hebrew, a local dialect of Tiberiade in Galilee which became the standard for the vocalization of the Jewish Bible ( Tanakh ) and, therefore, still influences all the other dialects of Hebrew. This Jewish Tiberiense from the seventh century to the 10th century is sometimes called “Biblical Jewish” since it is used to pronounce the Jewish Bible; However, it must be properly distinguished from the Vioh century Biblical Hebrew Bib, whose original pronunciation must be reconstructed. The Jewish Tiberiense incorporates the remarkable study made by the Masoreti (from Masoret which means “tradition”), which they added moth (vowels) and signs of candy (grammatical points) to the Jewish letters in order to preserve the previous characteristics of the Hebrew. [2] Even the Syriac alphabet, a precursor of the Arab alphabet, developed vocal punctuation systems, approximately in the same period. [twelfth] Aleppo’s code, a Jewish Bible with Masoretica punctuation, was written in the 10th century, perhaps to Tiberiade, and survives still today: it is probably the most important Jewish manuscript that exists. [13]

Between the 11th and the 11th century the study of the language took a fundamental step thanks to Yehudah Ben David Hayyuj, which established the laws that regulate the functioning of the language, in particular “trilitterism”, still considered precise today.

In the seventeenth century the drafting of the Jewish language compendium , written between 1670 and 1675 by the great philosopher Baruch Spinoza.

Modern language [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

The Hebrew entered its modern phase with the movement of the Haskalah (the Jewish Enlightenment) in Germany and Eastern Europe starting from the eighteenth century. Until the nineteenth century, which marked the beginnings of the Zionist movement, the Hebrew continued to act as a written language, especially for religious purposes, but also for other various purposes, such as philosophy, science, medicine and literature. Over the course of the whole 19th century the use that of Hebrew made itself for secular or worldly purposes by strengthening.

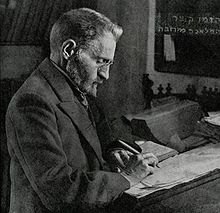

At the same time as the movement of the national Risorgimento, the activity aimed at transforming Jewish in the spoken language of the Jewish community into the land of Israel (the Yishuv) and for the Jews who immigrated to the Ottoman Palestine also began to transform. The linguist and enthusiast who gave practical implementation to the idea was Eliezer Ben Yehuda, a Lithuanian Jew who had emigrated to Palestine in 1881. It was he who created new words for the concepts related to modern life, which did not exist in classical Hebrew. The transition to Hebrew as a language of communication of the Yishuv in the land of Israel was relatively rapid. At the same time, the speech Jewish was also developing in other Jewish centers of Eastern Europe. [9]

Joseph Roth reports a story on Theodor Herzl and Ben Yehuda. This says that, a short time before the First Zionist Congress , in a bourgeois living room of Centreuropa, the journalist, as well as the founder of Zionism, Theodor Herzl met Ben Yehuda, who hoped to revive the ancient Jewish language, now relegated to the Saturday ritual only. Each of the two, hearing about the other about his utopia, pretended to grasp his charm, but, as soon as he left the interlocutor, he thought well of giving up and malignant as absurd and unsitively the purpose of these was. In spite of the detractors, both dreams were realized. [14]

With the establishment of the British agent government in the country, Jewish was established as a third official language, alongside Arabic and English. On the eve of the establishment of the state of Israel, it was already the main language of the Yishuv and was also used in schools and training institutes.

In 1948, the Hebrew became the official language of Israel, together with the Arabic. Nowadays, while maintaining a link with classic Hebrew, Hebrew is a language that is used in all fields of life, including science and literature. Inside there are influences from Yiddish, Arabic, Russian and English. There are about 9 million Israeli Locutors of Israeli, of which the vast majority resides in Israel. Lucky more than half are native locutors, that is, of Jewish mother tongue, while the remaining less than fifty percent has Jewish as a second language. [15]

On the basis of the European regulatory tradition, which finds its first expression in the establishment of the Accademia della Crusca (1585), also in Israel there is an official organ that dictates the linguistic standard: the Academy of the Jewish language. Although its real influence is limited, it operates with law. The Institute mainly deals with creating new terms and new lexical and morphosyntactic tools, through decisions that would be binding for institutional bodies and state school structures. In fact, most of his decisions are not accepted. The development of the sector of current use dictionaries in the Israel of the 90s produced some dictionaries and lexicas, which instead attest to the Royal Israeli Jewish language and which represent a source of alternative authority to the Academy of the Jewish language. [9] [16]

Orthodox Jews initially did not initially accept the idea of using the “Holy Language” for daily life and still in Israel some groups of ultra-orthodox Jews continue to use Yiddish for everyday life.

The Jewish communities of the diaspora continue to speak other languages, but the Jews who move to Israel have always had to learn this language to be able to enter. [2] [9]

Phonology [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

Biblical Jewish possessed a typically Semitic consonantism; e.g. The deaf and sound pharynges, a series of emphatic consonants (perhaps ejective, but this is much discussed), a lateral fricative, and in the oldest phases also deaf and sound uvularies. The latter two became pharyngeal, while / b g d k p t / suffered an alophication spirantization, transforming themselves, into certain positions, in / v, ɣ, ð, x, f, θ / (the so -called “begadkefat spirantization”). The primitive vocalism of biblical Hebrew included protosematic vowels / short and long, in addition to / or / long; But it changed considerably over time.

At the time of the Rotoli of the Dead Sea, the lateral fricative had turned into /s /in Jewish use, while among the Samaritans it had become /int /. Tiberiense vocalism had /a and i or u /, with /e /both closed and open, as well as ad /a and /just mentioned (or “decreased”); while other medieval reading systems owned a smaller number of vowels.

Some ancient reading systems have survived in liturgical traditions. In the Eastern Jewish tradition (sefarditis and Mizrahì) the emphatic consonants are pronounced as pharyngeals; While the Aschenazita tradition (central-eastern European) has lost both emphasis and pharyngeal, and /w /pass A /V /. The Samaritan tradition has a complex vowel repertoire, which does not always correspond to the Tiberiense system.

The pronunciation of modern Hebrew is derived from a set of different traditional reading methods, generally tending to simplification. The emphatic consonants are pronounced as non -emphatic equivalent, /w /as /v /, /ɣ ð θ /as /g d t /. Many Israelis, especially in the communities of European origin, assimilate sound pharynge to the blow of glottis, and the deaf pharling with deaf bounds, pronounce the consonants as simple as simple, and the / r / as a uvular vibration instead of alveolar, similarly to many variants of the Hebrew Aschenazita; Even the / h / tends to disappear. In contradiction with this strong tendency to the reduction of the number of traditional phonemes, other phonemes have become relatively frequent once absent or rare, such as /t͡s /, /d͡z /, c and g sweets, j French, and also /w /has reappeared; All this due to the adoption of many foreign words, especially neologisms. [17]

Morphology [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

Characteristic of the Hebrew, like other Semitic languages, is the root: a discontinuous morpheme in general or fourthononantic, from which words attributable to the same semantic field are derived. In Italian the Jewish roots are traditionally indicated by writing their capital consonants. The consonants of the root, writing in Hebrew, were usually transcribed by separating them with a point (e.g. כ.ת.ב); Today the grammatical conventions would impose the use of the dash (e.g. כ-ת-ב), since the point indicates a long break, while the dash connects. Similarly, the expression in a construct בδת-ספר ( Bet-Sefer “School”, lett. “House of the Book”) sees the use of the dash: in fact we do not find ourselves in front of the word בδ ( bayt “house”) separated from the other, ספר ( expedition “Book”), but we are faced with a single word composed of two elements in function of a common name. So for example also for the KTV root: the letters that represent it are not ת ת and ב, but the root is a unit with its specific meaning: כ-ת-ב. [18]

Much of scholars agree that they originally existed biconsonantic roots, such as ב-א and ק-ם (although according to the Academy of the Jewish language, these roots must be considered trilits: ב-ו and ק-ו).

The roots never appear alone as such in the language, but as members of the words, together with other morphemes. The root, modified by prefixes, suffixing and adequately vocalized, takes on different meanings. For example from the root כ-ת-ב KTV, attributable to the idea of the write , Derivano write ( that k h t O in ; “scrow”), letter ( me k h t a in ; “Letterra”), address ( kt O in And ; “indiezzo”), dictate ( Although k h t i in , “dictate”); From the root קשר qshr, which expresses the concept of connection, the words derive קשר ( k It is sh It is r , “Conteto Personale”) E Communications ( of ksh O r And , “communication”).

Mainly through the lexical loan, the modern Jewish also comes to create roots of four consonants and more, such as ד-ק-ס dsqs: לדסקס ( the d a sq It is s , often transcribed ledaskes “discuss”, from English to discuss ); o T-P-N-TLPN: Phone ( t It is l It is p O n , usually transcribed telephone , “telephone”, from the equivalent English or French word); or ט-ל-ר-פ TLGRP: לטלגרף ( the t a Lgr It is p , usually transcribed letalgref , from English or French “send a telegram”); FQSQS: ל-פ-ק-ס ( the f a qs It is s Usually transcribed liter , still from English to fax ).

Sometimes, modern Hebrew form neologisms through the combination of pre -existing lexical elements; In such cases, their roots are not easily defined in a traditional picture. For example, words such as רמזור ( ramzor “SemaForo”), o Moving ( Midrah “Strada, Isola Pedonale”), Derivate Rispettivamement Da Hint+Light E Squad+Street ( remez , “signal” e or , “light”, for “traffic light”; And midrakhah , “sidewalk” e Rehov “Via”, for “road, pedestrian island”). From the word ramzor However, a root was derived ר-מ-מ-ר rmzr, certified for example in the expression צומת מרומזר ( Tsomet Me r in mz a r “crossing with traffic light”).

The semantic link between words derived from the same root over time can become confused and is not necessarily evident or certain. Thus, for example, the verbs נפל ( nafal “Cadere”) hitnapel “Attach”) derive from the same root נ-פ-ל npl, although the two meanings have differentiated over time. The verbs פסל ( chapter “Annullare”) E Fisel ( piss “sculpting”), they would seem to derive from the same PSL root, but there is no semantic link between them, because the second comes from a root attested in Biblical Hebrew, while the first comes from an Aramaic word welcomed in Hebrew in a period later. Currently there is no consensus among linguists on the role of the root in the language. There are those who support the thesis that it represents an inseparable part of the lexical heritage, even if it appears only jointly with other morphemes, and there are those who see it as a linguistic manifestation of which the locutters are not necessarily aware at the intuitive level. [19]

Word [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

Verbs are expressed in seven forms ( binyanim , literally ‘constructions’), which usually change the meaning. The names of binyanim They derive from the root פעל (pa’al = work), except for the basic binyan, which is defined קל (qal = easy).

| Tell ( Pa’al ) | (Easy (act | active | Do |

| Nif’al | We will act | passive of the kal (pa’al) | be done |

| Fur | Fanil | intensive | do (usually) |

| Pu’al | Fike | Passivo del Pi’el | be done (usually) |

| Hif’il | Becoming | Causativo | make |

| Huf’al | And bellowed | passive of hif’il | be done |

| Hitpa’el | Counter | thoughtful | be |

Each Binyan has two verbal ways (indicative and infinite); In the indicative there are a present time, of the participial type, a past, a future and an imperative. There are no compound times (such as Italian transfers).

In the case, quite rare, of quadrilittere roots, the verb follows a flexion similar to the pi’el with splitting the median vowel: for example the verb לתפקד ( lethal , “work) to the past does תפקד ( tifked ) exactly as from לדבר ( ledaber ‘, speak) we have דδ ( Debar ). This occurs in the biblical language especially with loans from Persian in contemporary era, because of the loans from other modern languages you have to form neologisms and make up for the deficiencies of the biblical roots.

There is a distinction between male and female in the participial form of the present, and in some of the other two times (II and III singular, plural of the past; II and singular III of the future). [9] [20]

Nouns [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

As in the majority of modern Romance languages, there is a declination of the name only for the number and the genre. In the most common case, the original male name assumes a ה (vowel A + H Muta) final) or a ת- ( -t often with accent on the penultimate syllable) to the singular feminine, and the ending δ – ( -in the ) in the plural male, ות – ( -ot ) Plural female. But there are many male terms that have plural ending -ot while remaining male (and therefore any adjectives must be put to the plural in -in the : down = candela, nerot = candles, down the lava = Candela Bianca, Nerot Levanim = white candles). Another part of female terms, on the other hand, have male ending in -in the , while remaining feminine ( yonah = dove, side = dove, yonah levanah = white dove, Yonim Levanot = white doves).

In addition to singular and plural, numerous words admit a dual form, always written δ – but read -aim . The great majority of the dual terms are objects composed of two equal parts ( I am = bicycle, misparaim = scissors, mishqafaim = glasses) and almost all the double parts of the human and animal body, ( Birkaim = knees, shinnaim = teeth, I am notifying = ears, Sfataim = lips, yadaim = me, Eynaim = eyes, raw = ankles, leẖayaim = cheeks, ẖanikhaim = gums; but: Battey Seẖi = armpits), which normally want the female gender. [20]

The Hebrew is written from right to left. Its alphabet includes 22 letters of consonantic value (five of which have a distinct form at the end of the word) and some graphic signs developed in the relatively late period, aimed at representing the vowels. In fact, like the Arab one, the Jewish alphabet does not transcribe the vowels, if not in the form of small signs placed above, below or inside the consonants. As will be seen later, vocalization is importance for the meaning. See the Jewish alphabet voice for the list of letters and for phonetic correspondences. [21]

The system for transcription of the vowels, called נδ ( nowhere “Punta”), is usually not used in contemporary writings. In the books of the Bible, poetry and for children, it is instead common to indicate vocalization through the nowhere . The signs of nowhere , today municipalities were invented to Tiberiade in the seventh century in order to act as a mnemonic aid in reading the Bible. In the past there is also systems of nowhere alternative, which are no longer in use today. The essays of Tiberiade added to the first of the signs for the accents in the Bible. These indicate the pauses and ways of the entry with which the biblical verses must be read. The accents are now printed only in the Bible books. In all other texts it is used by the common interpretation signs developed in Europe and employed in most of the languages of the world. [21]

The best known and most evident feature of the letters of current Jewish writing is the squared form. The type of print used, called Frank Ruehl, is very widespread despite the criticisms that are moved for the fact that some letters are very similar to each other and therefore makes them difficult to distinguish. Ex.: א – צ, ג – נ, ב – כ, ו – ז, ח – ת, ר – ד.

The well -known Jewish alphabet known is a variant of the Aramaic alphabet used for the writing of the Aramaic empire , language of chancellery of the Persian Empire, who had replaced the Phoenician-Era-Era-Era-Era-Headaches employed in the Kingdom of Judah, in the Kingdom of Israel and in most of the ancient Middle East previously to the Babylonian captivity. The Jewish-French alphabet did not extinct completely, except after the Kokhba bar revolt. At the time of the Kokhba Rifonta Barba coin and adopted that alphabet for the writings. The same alphabet appears on the coins of today’s state of Israel, for example on the 1 -sized coin (1 nis).

Next to the printing form of the letters, or square alphabet, there is a cutting alphabet for quick writing; This writing is characterized by rounded lines and is very common in handwritten texts. The origin of this cursive writing is in the European Ashkenazite Jewish communities.

An alternative form of italics, now almost abandoned, is said rashi . He originated in the Sefarditis Jewish communities. This name derives from the fact that the first book to be printed in this alphabet was Rashi’s comment. This is used to use this alphabet to print traditional comments on the Bible and Talmud. Some attempts to introduce him also for the printing of texts in daily life were not successful, and today it is accepted only for the printing of traditional religious commentaries.

The pronunciation of the Hebrew has undergone great changes over the millennia of its existence. In the nineteenth century, the renewers of the Jewish language aspired to adopt the Spanish Jewish pronunciation, in particular the current one in the Spanish Jewish community of Jerusalem. This for the prestige of which the sefarditis Jewish community of Jerusalem was once enjoyed, and due to the fact that its pronunciation was extremely close to that attested by nowhere Massoretic to the Bible. However, most of the renewers of the Jewish language just as their supporters were Ashkenazi Jews of Eastern Europe, and the pronunciation of the Hebrew they knew was very different. Despite the efforts aimed at giving a sefarditis pronunciation to the Hebrew talked about again, the influence of the Ashkenazita pronunciation and the accent of the Yiddish language are clearly perceptible in modern Hebrew. [9] [21]

In Jewish Israeli practically there are no geographical dialects. The language, as it is listened to it pronounced by its native locutters, is in fact identical in all parts of Israel.

It is possible to warn a difference in emphasis in the Hebrew spoken by the various Jewish communities (ethnolets), but this difference is mainly expressed at a phonetic level, and not in syntax or morphology.

Some morphosyntactic differences can be manifested in relation to the level of language possessed (sociolets), but these are of relatively reduced importance.

The specificity of modern Hebrew lies in the fact that it serves to a great extent as a language convey Among people whose mother tongue is another, as the number of non -native speakers equivalent more or less to that of native speakers.

In Israel the Hebrew acts as a communication tool between the all theme community. For example, the knesset debates, in the courts etc. They take place in Hebrew, even if the various parts belong to groups whose language is not Jewish. [2]

Ethnologist [22] Identify the varieties currently talk about the Hebrew with the denominations Standard Hebrew (the Israeli standard, European, general, general use) and Oriental Hebrew (the “Eastern Jewish”, of Arabicizing pronunciation; the Jewish Yemenity).

These terms apply to the two varieties used for communication by the Israeli native speakers. “Arabicizing” does not mean that the Hebrew differs from the other variety due to an influence deriving from the Arabic. Rather, eastern Hebrew manages to maintain ancient characteristics due to the fact that they were shared with Arabic, while the same characteristics have been lost in other parts of the world where Jewish has lost contact with the Arabic language.

Immigrants are encouraged to adopt the Standard Hebrew as their own daily language. The Standard Jewish in the intentions of Eliezer Ben Yehuda, was to be based on the miserable spelling and the sefardized Jewish pronunciation. However, the first Jewish locutors were Yiddish native speakers, and often transferred to Jewish ways of saying and translations literally from Yiddish. Also phonologically this variety can be described as an amalgam of rulings, among which the sefarditis for vocalism stand out, and that Yiddish for some consonants, which are often not distinguished correctly. Thus, the language spoken in Israel has finished with the simplification and with the conformation to the phonology of Yiddish, in the following points:

- elimination of the pharyngeal joint of the letters It It is ‘ ivence

- the uvular pronunciation of resh

- the pronunciation of race come ey in some contexts ( Sify instead of digits , O taeysha instead of Tesha )

- the total removal of the sheva ( Zman , instead of zĕman according to the sefarditis pronunciation)

It is with this tendency to simplify that the unification of [t] and [s], to the Ashkenazita area of the phoneme / t / (having as a graphic counterpart ת), which converge in the single realization [t]. Many oriental or sefardi dialects present the same phenomenon, but the Jewish of Yemen and Iraq continue to differentiate the phonemes /t /and /θ /.

In Israel, above all, the pronunciation of Hebrew ends up reflecting the diasporic origin of the locutor, rather than adapting to the specific recommendations of the Academy. For this reason, more than half of the population pronounces the letter resh ר as [ʀ] (uvulant vibrant as in Yiddish and some German dialects), or as [ʁ] (sound uvulatory as in French or in other German dialects), and not as [r] (alveolar vibrant, as in Spanish or in Italian). The realization of this phoneme is often used by the Israelis as a modern Shibboleth, to determine the origin of those who come from another country.

There are different visions on the status of the two varieties. On the one hand, the Israelis of sefarditis or oriental origin are admired for the purity of their pronunciation, and often the Jews Yemenites work as announcers on the radio and in the news. On the other hand, the Ashkenazita pronunciation of the middle class is considered as sophisticated and Central European, so much so that many Mizrahi (Eastern) Jews approached this version of the standard Hebrew, even making the resh Uvular fricative. Once the inhabitants of the north of Israel pronounced the bet rafe (without dagesh ) as / b / in agreement with the traditional sefarditis pronunciation. This was perceived as rustic and today this pronunciation has disappeared. It can also be remembered that a gerosolimitano recognizes itself from its pronunciation of the word “two hundred” as Ma’aebit (word made elsewhere in the country as matayim ).

In the West Bank (Giudea and Samaria), as until some time ago also in the Gaza Strip, the Hebrew is the language of the administration, alongside the Arabic precisely to the majority of local populations. Contrary to the Arabs of Israeli citizenship, who learn Jewish through the school system since a young age, and lead their lives practically from bilinguals, most of the Arabs of the occupied territories, have Jewish only partially, when They do not ignore it completely. Despite this, the influence of Hebrew on their Arabic is clearly evident, especially in the quantity of loans. With the strengthening of the migratory flows of foreign workers towards Israel, a Jewish pidgin that acts as a means of communication between these workers and the Israeli Locutors of Hebrew has come. [23]

The influence of Hebrew stands in the languages of the Jews. The Jiddiš, spoken by the European Ashkenazite communities and whose origin is traced back to some German dialect, has borrowed many words from Hebrew (20% of its vocabulary). In the Jewish alphabet for how it has been adapted to jiddiš, part of the signs are reused to indicate the vowels. For example, the sign ע ( class ) finds employment to represent the phoneme /e /. However, lexical loans from Hebrew continue to respect the original spelling, despite the fact that the pronunciation can be very different. Thus, for example, the word אמת ( emits “Truth”, which, however, in Jiddiš is pronounced /Emes /) retains the original Jewish form and does not write “עמעס” (the phonetic writing of the Jewish and Aramaic terms of the jiddiš appears only in the Soviet jiddiš). A story jiddiš says that otherwise the name נח ( Noah , “Noè”) in jiddiš would write with seven errors, namely נאָctorעך Nojekh . [2] [23]

Judeo-Espanyol, also known as Spanish O Judezmo , and often said rogue , developed by Castilian and spoken by the Jewish communities of the sefarditis of the whole world, has also taken many words from the Hebrew, as well as being written in the Hebrew alphabet, and to be precise in Raši characters (although there is also a transcription system in Latin characters).

Strong influences of Hebrew are also found in the Caraima language, the idiom of the dear. The small caraime communities, ethnically and linguistically of Turkish origin, are scattered in some enclaves between Lithuania, Western Ukrainian and Crimea, and profess Caraism.

The Judeo-Georgian language is the variety of the Georgian language spoken by tradition by the Georgian Jews.

The Arab of the Jews, the language of the Jewish communities in the Muslim Empire, in particular in the Maghreb, in which they were written Mishneh Torah Maimonide and other important works, was also written in Jewish letters.

Other languages were influenced by Hebrew through the translations of the Bible. The word שבת ( Sabbat “Saturday”) for example it is widespread in many languages of the world to indicate the seventh day of the week (or the sixth, in the languages that count in order to drop as a seventh day on Sunday, for example in the Italian civil calendar, for the liturgy Cattolica The week begins at sunset on Saturday, as for the Jews), or to indicate a day of rest. The Jewish names of the biblical characters are also widespread all over the world. The two most common Jewish words in the various world languages are אמן ( amen “AMen”) E Hallelujah ( hallelujah “Alleluia”). [23]

Nobel Prizes for Jewish language literature [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

- ^ Nachman Gur, Behadrey Haredim, Kometz Aleph – Au• How many Hebrew speakers are there in the world? . are bhol.co.il . URL consulted on March 4, 2016 (archived by URL Original November 4, 2013) .

- ^ a b c d It is f g h i Angel Sáenz-Badilos, John Elwolde, A History of the Hebrew Language , Cambridge University Press, 1996, partic. Cap. I.

- ^ ( IN ) What are the top 200 most spoken languages? . are Ethnologist , 3 October 2018. URL consulted on May 27, 2022 .

- ^ Genesis 10.21 . are Laparola.net .

- ^ The library of forex . are lib.cet.ac.il . URL consulted on March 4, 2016 .

- ^ 2re 18.26 . are Laparola.net .

- ^ Isaiah 36.11 . are Laparola.net .

- ^ a b Allen P. Ross, Introducing Biblical Hebrew , Baker Academic, 2001, S.V.

- ^ a b c d It is f g Joel M. Hoffman, In the Beginning: A Short History of the Hebrew Language , Nyu Press. ISBN 0-8147-3654-8; See also the all -inclusive site History of the Hebrew Language , under the respective chapters and voices (files also downloadable in PDF). Eurl consulted March 4, 2016

- ^ Specifically, see Maimonidea guide , Part II, peculiar. head. 5.

- ^ B. Spolsky, “Jewish Multilingualism in the First century: An Essay in Historical Sociolinguistics”, Joshua A. Fishman (cur.), Readings in The Sociology of Jewish Languages , E. J. Brill, 1985, p. 40. & passim .

- ^ William Hatch, An album of dated Syriac manuscripts , The American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 1946, RIST. 2002 Gorgias Press, p. 24. ISBN 1-931956-53-7

- ^ Hayim Tawil & Bernard Schneider, Crown of Aleppo , Jewish Publication Soc., 2010, p. 110; Regarding the text, there are various reports and estimates about the original number of pages; Izhak Ben-Zvi, “The Codex of Ben Asher”, Tissue , Vol. 1, 1960, p. 2, rist. In Sid Z. Leman, Cur., The Canon and Masorah of the Hebrew Bible, an Introductory Reader , Ktav Pubg. House, 1974, p. 758 (estimate of 380 original pages).

- ^ Wandering Jews , Adelphi. [to be verified: in the last edition Adelphi there is no trace of the anecdote]

- ^ Zuckernn, Gilg, Revivalistics: From the Genesis of Israeli to Language Reclamation in Australia and Beyond . Oxford University Press , 2020. (ISBN 9780199812790 / ISBN 97801998812776)

- ^ “Eliezer Ben Yehuda and the Resurgence of the Hebrew Language” by Libby Kantorwitz.url Consultated March 4, 2016

- ^ Asher Laufer, Hebrew Handbook of the International Phonetic Association , Cambridge University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-521-65236-7

- ^ The Ergyzer trailer, Jewish is easy , Achiasav, Tel Aviv, and Giuntina, Florence 1990.

- ^ Lewis Glinert, Modern Hebrew. An Essential Grammar , Routledge, New York and Oxon 2005, pp. 44-76 & passim .

- ^ a b For this section, see Doron Mittler, Jewish grammar , Zanichelli, 2000, “verbs”. Isbn 978-88-08-09733-0

- ^ a b c For all this section, see mainly History of Hebrew, cit. , “Scripts and Scripture” and related chapters.

- ^ The voice Hebrew in Ethnologist

- ^ a b c For all this section, see mainly History of Hebrew, cit. , Excurses 3-8 : “Some Differences Between Biblical and Israeli Hebrew”, “Background to Dialect, Koine and Diglossia in Ancient Hebrew Clarification from Colloquial Arabic”, et al. URL consulted March 4, 2016

- ^ In the Jewish-Polacca cultural tradition, Isaac Bashevis Singer won the Nobel Prize for Literature of Language Yiddish in 1978, a language written with the characters of the Jewish alphabet.

Biblical language [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

- Wilhelm Gesenius, Emil Kautzsch, Arthur Ernst Cowley, Gesenius’ Hebrew Grammar , Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2nd Edizione, 1910

- Roland K. Harrison, Teach Yourself Biblical Hebrew , Sevenoaks, Hodder and Stoughton, 1955

- Sarah Nicholson, Teach Yourself Biblical Hebrew , Londra, Hodder Arnold, 2006

- Jacob Weingreen, A Practical Grammar for Classical Hebrew , Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1959

- Thomas Lambdin, Introduction to Biblical Hebrew , Darton, Longman & Todd, 1971

- Giovanni Lenzi, The Jewish verbal system. An educational approach , Marzabotto (Bo), Edizioni Zikkaron, 2017, ISBN 978-88-99720-07-0

Lingua Mishnaica [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

- M.H. Segal, A Grammar of Mishnaic Hebrew , Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1927

- Miguel Perez Fernandez, translated by John Elwolde, An Introductory Grammar of Rabbinic Hebrew , Brill, Leiden 1999

Modern language [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

- Olivier Durand, Dario Burgaretta, Contemporary Hebrew course , Hoepli, Milan, 2013, ISBN 978-8820357030

- Carlo Alberto Viterbo, A way to Hebrew , Rome, Carucci, 1981

- The Ergyzer trailer, Jewish is easy , Tel Aviv, Achiasav; Florence, Giuntina, 1990

- Genya Nahmani Geppi, Jewish grammar , Milan, A. Vallardi, 1997

- Doron Mittler, Jewish grammar , Bologna, Zanichelli, 2000 (ISBN 978-8-08-033-0)

- Lewis Glinert, The Grammar of Modern Hebrew , Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1989

- Lewis Glinert, Modern Hebrew. An Essential Grammar , New York and Oxon, Routledge, 2005

- Zippy Littleton and Tamar Wang, Colloquial Hebrew , Londra, Routledge, 2004

- Shula Gilboa, Teach Yourself Modern Hebrew , Londra, Hodder Arnold, 2004

History of the language [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

- Louis-Jean Calvet, Hebrew, a language with eclipses , in: The Mediterranean. Sea of our languages , Cap. 4, PP. 63-84, Paris, CNRS vesditions, 2016, ISBN 978-2-271-08902-1

- Giovanni Barbini, Olivier Durand, Introduction to Semitic languages , Brescia, Paidaia, 1994, Isbn 88-394-0506-2

- Giovanni Garbini, Introduction to Semitic epigraphy , Brescia, Paidaia, 2006, Isbn 88-394-016-26

- Olivier Durand, The Jewish language. Historical-structural profile , Bresia, Paideia, 2001

- Angel Saenz-Badillos, History of the Hebrew language , Sabadell, Editorial Ausa, 1988, ISBN 8-486-32932-9

- Angel Saenz-Badillos, A History of the Hebrew Language , translation by John Elwolde, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1993

- Angel Saenz-Badillos, History of the Jewish language , translation by Piero Capelli, Brescia, Paideia, 2007

- Joel M. Hoffman, In the Beginning: A Short History of the Hebrew Language , New York, NYU Press, 2006

- Mireille Fairy-Lebel, History of the Hebrew language of origins at the time of Mishna , Paris, Publications Oientalists de France, 4this edition, 1986

- Mireille Fairy-Lebel, Hebrew, three thousand years of history , Paris, Albin Michel, 1992

- Mireille Fairy-Lebel, History of the Jewish language , translation by Vanna Lucattini Vogelmann, Florence, Giuntina, 1994

- Giulio Busi, The enigma of Hebrew in the Renaissance , Turin, Aragno, 2007

- Edited by Lewis Glinert, Hebrew in Ashkenaz , Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1993

- Eliezer Ben-Yehuda, Ihamar Ben-Avi, The rebirth of Hebrew , Paris, despulate de brouwers, 1998

- Ilan Stavans, Resurrecting Hebrew , New York, Shocken Books, 2008

- William Chomsky, Hebrew: The Eternal Language , Philadelphia, The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1957, ISBN 0-8276-0077-1 (Sixth Printing, 1978)

- Paul Wexler, The schizoid nature of Modern Hebrew: A Slavic language in search of a semitic past , Wiesbaden, Harrassowitz, 1990, ISBN 978-3447030632

- Zuckernn, Gilk, 2003. Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew . Palgrave Macmillan. (ISBN 9781403917232 / ISBN 9781403938695)

Language and culture [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

- ( IN ) Lewis Glinert, The Joys of Hebrew , New York, Oxford University Press, 1992.

- ( IN ) David Patterson, Hebrew Language and Jewish Thought , Abingdon, Routledge, 2005.

- Sarah Kaminski, Maria Teresa Milano, Jewish , Bologna, EDB, 2018, ISBN 978-88-10-43216-7.

- Anna Linda Callow, The language he lived twice. Charm and adventures of Hebrew , Milan, Garzanti, 2019, ISBN 978-88-11-60353-5.

- Jewish . are sape.it , De Agostini.

- ( IT , OF , FR ) Jewish language . are HLS-DHS-DSS , Historical dictionary of Switzerland.

- ( IN ) Jewish language . are British encyclopedia Encyclopaedia Britannica, Inc.

- ( IN ) Jewish language , in Catholic Encyclopedia , Robert Appleton Company.

- ( IN ) Jewish language . are Ethnologue: Languages of the World , Ethnologist.

Recent Comments