Nuclear power in the United States

Power source providing US electricity

Net electrical generation from US nuclear power plants 1957–2019

Nuclear power compared to other sources of electricity in the US, 1949–2011

Nuclear power in the United States is provided by 92 commercial reactors with a net capacity of 94.7 gigawatts (GW), with 61 pressurized water reactors and 31 boiling water reactors. [first] In 2019, they produced a total of 809.41 terawatt-hours of electricity, [2] which accounted for 20% of the nation’s total electric energy generation. [3] In 2018, nuclear comprised nearly 50 percent of US emission-free energy generation. [4] [5]

As of September 2017 [update] , there are two new reactors under construction with a gross electrical capacity of 2,500 MW, while 39 reactors have been permanently shut down. [6] [7] The United States is the world’s largest producer of commercial nuclear power, and in 2013 generated 33% of the world’s nuclear electricity. [8] With the past and future scheduled plant closings, China and Russia could surpass the United States in nuclear energy production. [9]

As of October 2014, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) has granted license renewals providing 20-year extensions to a total of 74 reactors. In early 2014, the NRC prepared to receive the first applications of license renewal beyond 60 years of reactor life as early as 2017, a process which by law requires public involvement. [ten] Licenses for 22 reactors are due to expire before the end of 2029 if no renewals are granted. [11] Pilgrim Nuclear Power Station in Massachusetts was the most recent nuclear power plant to be decommissioned, on June 1, 2019. Another five aging reactors were permanently closed in 2013 and 2014 before their licenses expired because of high maintenance and repair costs at a time when natural gas prices had fallen: San Onofre 2 and 3 in California, Crystal River 3 in Florida, Vermont Yankee in Vermont, and Kewaunee in Wisconsin. [twelfth] [13] In April 2021, New York State permanently closed Indian Point in Buchanan, 30 miles from New York City. [13] [14]

Most reactors began construction by 1974; following the Three Mile Island accident in 1979 and changing economics, many planned projects were cancelled. More than 100 orders for nuclear power reactors, many already under construction, were canceled in the 1970s and 1980s, bankrupting some companies. Up until 2013, there had also been no ground-breaking on new nuclear reactors at existing power plants since 1977. Then in 2012, the NRC approved construction of four new reactors at existing nuclear plants. Construction of the Virgil C. Summer Nuclear Generating Station Units 2 and 3 began on March 9, 2013, but was abandoned on July 31, 2017, after the reactor supplier Westinghouse filed for bankruptcy protection in March 2017. [15] On March 12, 2013, construction began on the Vogtle Electric Generating Plant Units 3 and 4. The target in-service date for Unit 3 was originally November 2021. [16] In March of 2023, the Vogtle reached “initial criticality” and is scheduled to start service in May or June of 2023. [17] On October 19, 2016, TVA’s Unit 2 reactor at the Watts Bar Nuclear Generating Station became the first US reactor to enter commercial operation since 1996. [18] In 2006 the Brookings Institution, a public policy organization, stated that new nuclear units had not been built in the United States because of soft demand for electricity, the potential cost overruns on nuclear reactors due to regulatory issues and resulting construction delays. [19]

There was a revival of interest in nuclear power in the 2000s, with talk of a “nuclear renaissance”, supported particularly by the Nuclear Power 2010 Program. A number of applications were made, but facing economic challenges, and later in the wake of the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, most of these projects have been cancelled.

History [ edit ]

Emergence [ edit ]

Research into the peaceful uses of nuclear materials began in the United States under the auspices of the Atomic Energy Commission, created by the United States Atomic Energy Act of 1946. Medical scientists were interested in the effect of radiation upon the fast-growing cells of cancer, and materials were given to them, while the military services led research into other peaceful uses.

Power reactor research [ edit ]

Argonne National Laboratory was assigned by the United States Atomic Energy Commission the lead role in developing commercial nuclear energy beginning in the 1940s. Between then and the turn of the 21st century, Argonne designed, built, and operated fourteen reactors [20] at its site southwest of Chicago, and another fourteen reactors [20] at the National Reactors Testing Station in Idaho. [21] These reactors included initial experiments and test reactors that were the progenitors of today’s pressurized water reactors (including naval reactors), boiling water reactors, heavy water reactors, graphite-moderated reactors, and liquid-metal cooled fast reactors, one of which [22] was the first reactor in the world to generate electricity. Argonne and a number of other AEC contractors built a total of 52 reactors at the National Reactor Testing Station. Two were never operated; except for the Neutron Radiography Facility, all the other reactors were shut down by 2000.

In the early afternoon of December 20, 1951, Argonne director Walter Zinn and fifteen other Argonne staff members witnessed a row of four light bulbs light up in a nondescript brick building in the eastern Idaho desert. Electricity from a generator connected to Experimental Breeder Reactor I (EBR-I) flowed through them. This was the first time that a usable amount of electrical power had ever been generated from nuclear fission. Only days afterward, the reactor produced all the electricity needed for the entire EBR complex. [23] One ton of natural uranium can produce more than 40 gigawatt-hours of electricity — this is equivalent to burning 16,000 tons of coal or 80,000 barrels of oil. [24] More central to EBR-I’s purpose than just generating electricity, however, was its role in proving that a reactor could create more nuclear fuel as a byproduct than it consumed during operation. In 1953, tests verified that this was the case. [25]

The US Navy took the lead, seeing the opportunity to have ships that could steam around the world at high speeds for several decades without needing to refuel, and the possibility of turning submarines into true full-time underwater vehicles. So, the Navy sent their “man in Engineering”, then Captain Hyman Rickover, well known for his great technical talents in electrical engineering and propulsion systems in addition to his skill in project management, to the AEC to start the Naval Reactors project. Rickover’s work with the AEC led to the development of the Pressurized Water Reactor (PWR), the first naval model of which was installed in the submarine USS Nautilus . This made the boat capable of operating under water full-time – demonstrating this ability by reaching the North Pole and surfacing through the Polar ice cap.

Start of commercial nuclear power [ edit ]

From the successful naval reactor program, plans were quickly developed for the use of reactors to generate steam to drive turbines turning generators. In April 1957, the SM-1 Nuclear Reactor in Fort Belvoir, Virginia was the first atomic power generator to go online and produce electrical energy to the U.S. power grid. On May 26, 1958, the first commercial nuclear power plant in the United States, Shippingport Atomic Power Station, was opened by President Dwight D. Eisenhower as part of his Atoms for Peace program. As nuclear power continued to grow throughout the 1960s, the Atomic Energy Commission anticipated that more than 1,000 reactors would be operating in the United States by 2000. [26] As the industry continued to expand, the Atomic Energy Commission’s development and regulatory functions were separated in 1974; the Department of Energy absorbed research and development, while the regulatory branch was spun off and turned into an independent commission known as the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (USNRC or simply NRC).

Pro-nuclear power stance [ edit ]

As of February 2020, Our World In Data stated that “nuclear energy and renewables are far, far safer than fossil fuels as regards human health, safety and carbon footprint,” with nuclear energy resulting in 99.8% fewer deaths than brown coal; 99.7% fewer than coal; 99.6% fewer than oil; and 97.5% fewer than gas. [27]

Under President Obama, the Office of nuclear energy stated in January 2012 that “Nuclear power has safely, reliably, and economically contributed almost 20% of electrical generation in the United States over the past two decades. It remains the single largest contributor (more than 70%) of non-greenhouse-gas- emitting electric power generation in the United States. Domestic demand for electrical energy is expected to grow by more than 30% from 2009 to 2035. At the same time, most of the currently operating nuclear power plants will begin reaching the end of their initial 20-year extension to their original 40-year operating license, for a total of 60 years of operation.” It warned that if new plants do not replace those which are retired then the total fraction of generated electrical energy from nuclear power will begin to decline. [28]

The United States Department of Energy web site states that “nuclear power is the most reliable energy source”, and to a great degree “has the highest capacity factor. Natural gas and coal capacity factors are generally lower due to routine maintenance and/or refueling at these facilities while renewable plants are considered intermittent or variable sources and are mostly limited by a lack of fuel (i.e. wind, sun, or water).” [29] Nuclear is the largest source of clean power in the United States, generating more than 800 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity each year and producing more than half of the nation’s emissions-free electricity. This avoids more than 470 million metric tons of carbon each year, which is the equivalent of removing 100 million cars off of the road. In 2019, nuclear plants operated at full power more than 93% of the time, making it the most reliable energy source on the power grid. The Department of Energy and its national labs are working with industry to develop new reactors and fuels that will increase the overall performance of nuclear technologies and reduce the amount of nuclear waste that is produced. [30]

Advanced nuclear reactors “that are smaller, safer, and more efficient at half the construction cost of today’s reactors” are part of President Biden’s clean energy proposals. [thirty first]

Opposition to nuclear power [ edit ]

There has been considerable opposition to the use of nuclear power in the United States. The first U.S. reactor to face public opposition was Enrico Fermi Nuclear Generating Station in 1957. It was built approximately 30 miles from Detroit and there was opposition from the United Auto Workers Union. [32] Pacific Gas & Electric planned to build the first commercially viable nuclear power plant in the US at Bodega Bay, north of San Francisco. The proposal was controversial and conflict with local citizens began in 1958. [33] The conflict ended in 1964, with the forced abandonment of plans for the power plant. Historian Thomas Wellock traces the birth of the anti-nuclear movement to the controversy over Bodega Bay. [33] Attempts to build a nuclear power plant in Malibu were similar to those at Bodega Bay and were also abandoned. [33]

Nuclear accidents continued into the 1960s with a small test reactor exploding at the Stationary Low-Power Reactor Number One in Idaho Falls in January 1961 and a partial meltdown at the Enrico Fermi Nuclear Generating Station in Michigan in 1966. [34] In his 1963 book Change, Hope and the Bomb , David Lilienthal criticized nuclear developments, particularly the nuclear industry’s failure to address the nuclear waste question. [35] J. Samuel Walker, in his book Three Mile Island: A Nuclear Crisis in Historical Perspective , explains that the growth of the nuclear industry in the U.S. occurred in the 1970s as the environmental movement was being formed. Environmentalists saw the advantages of nuclear power in reducing air pollution, but were critical of nuclear technology on other grounds. [36] They were concerned about nuclear accidents, nuclear proliferation, high cost of nuclear power plants, nuclear terrorism and radioactive waste disposal. [37]

There were many anti-nuclear protests in the United States which captured national public attention during the 1970s and 1980s. These included the well-known Clamshell Alliance protests at Seabrook Station Nuclear Power Plant and the Abalone Alliance protests at Diablo Canyon Nuclear Power Plant, where thousands of protesters were arrested. Other large protests followed the 1979 Three Mile Island accident. [38]

In New York City on September 23, 1979, almost 200,000 people attended a protest against nuclear power. [39] Anti-nuclear power protests preceded the shutdown of the Shoreham, Yankee Rowe, Rancho Seco, Maine Yankee, and about a dozen other nuclear power plants. [40]

Historical use of Native land in nuclear energy [ edit ]

Nuclear Energy in the United States has greatly affected Native Americans due to the large amount of mining for uranium, and disposal of nuclear waste done on Native lands over the past century. [41] [42] [43] [44] Environmental Sociologists Chad L. Smith and Gregory Hooks have deemed these areas and tribal lands as a whole “sacrifice zones”, [42] due to the prevalence of mishandled nuclear materials. Uranium as a resource has largely been located in the southwestern USA, and large amounts have been found on Native lands, with the estimates being anywhere from 25% to 65% of Uranium being located on Native land. [41] Due to this many mines have been placed on Native land and have been abandoned without proper closing of these mines. [44] Some of these mines have led to large amounts of pollution on Native land which has contaminated the water and ground. [41] This has led to a large uptick in cancer cases. [44] On the Navajo reservation in particular, there has been three separate cleanup efforts done by the EPA, all unsuccessful. [44]

Nuclear waste has been an issue that Native Americans have had to deal with for decades ranging from improper disposal of waste during active mining to the government trying and succeeding to place waste disposal sites on various native lands. [45] In 1986 the US government tried to put a permanent nuclear waste repository on the White Earth Reservation, but the Anishinaabe people who lived there commissioned the Minnesota legislature to prevent it, which worked. [45] However, because there was no permanent place found, the government placed a temporary facility on Yucca Mountain to contain the waste. [45] Yucca Mountain is also on Native Land and is considered a sacred site that the government did not have consent to place nuclear waste on. [45] [forty six] Yucca Mountain still houses this temporary facility to this day and is being debated over if it should become a permanent facility. [45]

Over-commitment and cancellations [ edit ]

By the mid-1970s, it became clear that nuclear power would not grow nearly as quickly as once believed. Cost overruns were sometimes a factor of ten above original industry estimates, and became a major problem. For the 75 nuclear power reactors built from 1966 to 1977, cost overruns averaged 207 percent. Opposition and problems were galvanized by the Three Mile Island accident in 1979. [47]

Over-commitment to nuclear power brought about the financial collapse of the Washington Public Power Supply System, a public agency which undertook to build five large nuclear power plants in the 1970s. By 1983, cost overruns and delays, along with a slowing of electricity demand growth, led to cancellation of two WPPSS plants and a construction halt on two others. Moreover, WPPSS defaulted on $2.25 billion of municipal bonds, which is one of the largest municipal bond defaults in U.S. history. The court case that followed took nearly a decade to resolve. [48] [49] [50]

Eventually, more than 120 reactor orders were cancelled, [51] and the construction of new reactors ground to a halt. Al Gore has commented on the historical record and reliability of nuclear power in the United States:

Of the 253 nuclear power reactors originally ordered in the United States from 1953 to 2008, 48 percent were canceled, 11 percent were prematurely shut down, 14 percent experienced at least a one-year-or-more outage, and 27 percent are operating without having a year-plus outage. Thus, only about one fourth of those ordered, or about half of those completed, are still operating and have proved relatively reliable. [52]

Amory Lovins has also commented on the historical record of nuclear power in the United States:

Of all 132 U.S. nuclear plants built (52% of the 253 originally ordered), 21% were permanently and prematurely closed due to reliability or cost problems, while another 27% have completely failed for a year or more at least once. The surviving U.S. nuclear plants produce ~90% of their full-time full-load potential, but even they are not fully dependable. Even reliably operating nuclear plants must shut down, on average, for 39 days every 17 months for refueling and maintenance, and unexpected failures do occur too. [53]

A cover story in the February 11, 1985, issue of Forbes magazine commented on the overall management of the nuclear power program in the United States:

The failure of the U.S. nuclear power program ranks as the largest managerial disaster in business history, a disaster on a monumental scale … only the blind, or the biased, can now think that the money has been well spent. It is a defeat for the U.S. consumer and for the competitiveness of U.S. industry, for the utilities that undertook the program and for the private enterprise system that made it possible. [54]

Three Mile Island and after [ edit ]

The NRC reported “(…the Three Mile Island accident…) was the most serious in U.S. commercial nuclear power plant operating history, even though it led to no deaths or injuries to plant workers or members of the nearby community.” [55] The World Nuclear Association reports that “…more than a dozen major, independent studies have assessed the radiation releases and possible effects on the people and the environment around TMI since the 1979 accident at TMI-2. The most recent was a 13-year study on 32,000 people. None has found any adverse health effects such as cancers which might be linked to the accident.” [56] Other nuclear power incidents within the US (defined as safety-related events in civil nuclear power facilities between INES Levels 1 and 3 [57] include those at the Davis-Besse Nuclear Power Plant, which was the source of two of the top five highest conditional core damage frequency nuclear incidents in the United States since 1979, according to the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission. [58]

Despite the concerns which arose among the public after the Three Mile Island incident, the accident highlights the success of the reactor’s safety systems. The radioactivity released as a result of the accident was almost entirely confined within the reinforced concrete containment structure. These containment structures, found at all nuclear power plants, were designed to successfully trap radioactive material in the event of a melt down or accident. At Three Mile Island, the containment structures operated exactly as it was designed to do, emerging successful in containing any radioactive energy. The low levels of radioactivity released post incident is considered harmless, resulting in zero injuries and deaths of residents living in proximity to the plant.

Despite many technical studies which asserted that the probability of a severe nuclear accident was low, numerous surveys showed that the public remained “very deeply distrustful and uneasy about nuclear power”. [59] Some commentators have suggested that the public’s consistently negative ratings of nuclear power are reflective of the industry’s unique connection with nuclear weapons: [60]

[One] reason why nuclear power is seen differently to other technologies lies in its parentage and birth. Nuclear energy was conceived in secrecy, born of war, and first revealed to the world in horror. No matter how many proponents try to separate the peaceful atom from the weapon’s atom, the connection is firmly embedded in the mind of the public. [60]

Several US nuclear power plants closed well before their design lifetimes, due to successful campaigns by anti-nuclear activist groups. [sixty one] These include Rancho Seco in 1989 in California and Trojan in 1992 in Oregon. Humboldt Bay in California closed in 1976, 13 years after geologists discovered it was built on the Little Salmon Fault. Shoreham Nuclear Power Plant was completed but never operated commercially as an authorized Emergency Evacuation Plan could not be agreed on due to the political climate after the Three Mile Island accident and Chernobyl disaster. The last permanent closure of a US nuclear power plant was in 1997. [62]

US nuclear reactors were originally licensed to operate for 40-year periods. In the 1980s, the NRC determined that there were no technical issues that would preclude longer service. [63] Over half of US nuclear reactors are over 30 years old and almost all are over twenty years old. [sixty four] As of 2011 [update] , more than 60 reactors have received 20-year extensions to their licensed lifetimes. [65] The average capacity factor for all US reactors has improved from below 60% in the 1970s and 1980s, to 92% in 2007. [66] [sixty seven]

After the Three Mile Island accident, NRC-issued reactor construction permits, which had averaged more than 12 per year from 1967 through 1978, came to an abrupt halt; no permits were issued between 1979 and 2012 (in 2012, four planned new reactors received construction permits). Many permitted reactors were never built, or the projects were abandoned. Those that were completed after Three Mile island experienced a much longer time lag from construction permit to starting of operations. The Nuclear Regulatory Commission itself described its regulatory oversight of the long-delayed Seabrook Nuclear Power Plant as “a paradigm of fragmented and uncoordinated government decision making,” and “a system strangling itself and the economy in red tape.” [68] The number of operating power reactors in the US peaked at 112 in 1991, far fewer than the 177 that received construction permits. By 1998 the number of working reactors declined to 104, where it remains as of 2013. The loss of electrical generation from the eight fewer reactors since 1991 has been offset by power uprates of generating capacity at existing reactors. [69]

Despite the problems following Three Mile Island, output of nuclear-generated electricity in the US grew steadily, more than tripling over the next three decades: from 255 billion kilowatt-hours in 1979 (the year of the Three Mile Island accident), to 806 billion kilowatt-hours in 2007. [70] Part of the increase was due to the greater number of operating reactors, which increased by 51%: from 69 reactors in 1979, to 104 in 2007. Another cause was a large increase in the capacity factor over that period. In 1978, nuclear power plants generated electricity at only 64% of their rated output capacity. Performance suffered even further during and after Three Mile Island, as a series of new safety regulations from 1979 through the mid-1980s forced operators to repeatedly shut down reactors for required retrofits. [71] It was not until 1990 that the average capacity factor of US nuclear plants returned to the level of 1978. The capacity factor continued to rise, until 2001. Since 2001, US nuclear power plants have consistently delivered electric power at about 90% of their rated capacity. [72] In 2016, the number of power plants was at 100 with 4 under construction.

Effects of Fukushima [ edit ]

Following the 2011 Japanese nuclear accidents, the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission announced it would launch a comprehensive safety review of the 104 nuclear power reactors across the United States, at the request of President Obama. A total of 45 groups and individuals had formally asked the NRC to suspend all licensing and other activities at 21 proposed nuclear reactor projects in 15 states until the NRC had completed a thorough post-Fukushima reactor crisis examination. The petitioners also asked the NRC to supplement its own investigation by establishing an independent commission comparable to that set up in the wake of the serious, though less severe, 1979 Three Mile Island accident. [74] [75] The Obama administration continued “to support the expansion of nuclear power in the United States, despite the crisis in Japan”. [76]

An industry observer noted that post-Fukushima costs were likely to go up for both current and new nuclear power plants, due to increased requirements for on-site spent fuel management and elevated design basis threats. [77] [78] License extensions for existing reactors will face additional scrutiny, with outcomes depending on plants meeting new requirements, and some extensions already granted for more than 60 of the 100 operating U.S. reactors could be revisited. On-site storage, consolidated long-term storage, and geological disposal of spent fuel is “likely to be reevaluated in a new light because of the Fukushima storage pool experience”. [77] Mark Cooper suggested that the cost of nuclear power, which already had risen sharply in 2010 and 2011, could “climb another 50 percent due to tighter safety oversight and regulatory delays in the wake of the reactor calamity in Japan”. [79]

In 2011, London-based bank HSBC said: “With Three Mile Island and Fukushima as a backdrop, the US public may find it difficult to support major nuclear new build and we expect that no new plant extensions will be granted either. Thus we expect the clean energy standard under discussion in US legislative chambers will see a far greater emphasis on gas and renewables plus efficiency”. [80]

Competitiveness problems [ edit ]

In May 2015, a senior vice president of General Atomics stated that the U.S. nuclear industry was struggling because of comparatively low U.S. fossil fuel production costs, partly due to the rapid development of shale gas, and high financing costs for nuclear plants. [81]

In July 2016, Toshiba withdrew the U.S. design certification renewal for its Advanced Boiling Water Reactor because “it has become increasingly clear that energy price declines in the US prevent Toshiba from expecting additional opportunities for ABWR construction projects”. [82]

In 2016, Governor of New York Andrew Cuomo directed the New York Public Service Commission to consider ratepayer-financed subsidies similar to those for renewable sources to keep nuclear power stations profitable in the competition against natural gas. [83] [84]

In March 2018, FirstEnergy announced plans to deactivate the Beaver Valley, Davis-Besse, and Perry nuclear power plants, which are in the Ohio and Pennsylvania deregulated electricity market, for economic reasons during the next three years. [85]

In 2019, the Energy Information Administration revised the levelized cost of electricity from new advanced nuclear power plants to be $0.0775/kWh before government subsidies, using a 4.3% cost of capital (WACC) over a 30-year cost recovery period. [eighty six] Financial firm Lazard also updated its levelized cost of electricity report costing new nuclear at between $0.118/kWh and $0.192/kWh using a commercial 7.7% cost of capital (WACC) (pre-tax 12% cost for the higher-risk 40% equity finance and 8% cost for the 60% loan finance) over a 40-year lifetime, making it the most expensive privately financed non-peaking generation technology other than residential solar PV. [eighty seven]

In August 2020, Exelon decided to close the Byron and Dresden plants in 2021 for economic reasons, despite the plants having licenses to operate for another 20 and 10 years respectively. On September 13, 2021, the Illinois Senate approved a bill containing nearly $700 million in subsidies for the state’s nuclear plants, including Byron, causing Exelon to reverse the shutdown order. [88] [89]

Westinghouse Chapter 11 bankruptcy [ edit ]

On March 29, 2017, parent company Toshiba placed Westinghouse Electric Company in Chapter 11 bankruptcy because of $9 billion of losses from its nuclear reactor construction projects. The projects responsible for this loss are mostly the construction of four AP1000 reactors at Vogtle in Georgia and V. C. Summer in South Carolina. [90] The U.S. government had given $8.3 billion of loan guarantees for the financing of the Vogtle nuclear reactors being built in the U.S., which are delayed but remain under construction. [91] In July 2017, the V.C. Summer plant owners, the two largest utilities in South Carolina, terminated the project. [91] Peter A. Bradford, former Nuclear Regulatory Commission member, commented “They placed a big bet on this hallucination of a nuclear renaissance”. [92]

The other U.S. new nuclear supplier, General Electric, had already scaled back its nuclear operations as it was concerned about the economic viability of new nuclear. [93]

In the 2000s, interest in nuclear power renewed in the US, spurred by anticipated government curbs on carbon emissions, and a belief that fossil fuels would become more costly. [ninety four] Ultimately however, following Westinghouse’s bankruptcy, only two new nuclear reactors were under construction. In addition Watts Bar unit 2, whose construction was started in 1973 but suspended in the 1980s, was completed and commissioned in 2016.

Possible renaissance [ edit ]

In 2008, it was reported that The Shaw Group and Westinghouse would construct a factory at the Port of Lake Charles at Lake Charles, Louisiana to build components for the Westinghouse AP1000 nuclear reactor. [95] On October 23, 2008, it was reported that Northrop Grumman and Areva were planning to construct a factory in Newport News, Virginia to build nuclear reactors. [96]

As of March 2009, the NRC had received applications to construct 26 new reactors [97] with applications for another 7 expected. [98] [99] Six of these reactors were ordered. [100] Some applications were made to reserve places in a queue for government incentives available for the first three plants based on each innovative reactor design. [98]

In May 2009, John Rowe, chairman of Exelon, which operates 17 nuclear reactors, stated that he would cancel or delay construction of two new reactors in Texas without federal loan guarantees. [101] Following the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster in Japan, he remarked that the nuclear renaissance was dead. [ citation needed ] Amory Lovins added that “market forces had killed it years earlier”. [102]

In July 2009, the proposed Victoria County Nuclear Power Plant was delayed, as the project proved difficult to finance. [103] As of April 2009 [update] , AmerenUE has suspended plans to build its proposed plant in Missouri because the state Legislature would not allow it to charge consumers for some of the project’s costs before the plant’s completion. The New York Times has reported that without that “financial and regulatory certainty” the company has said it could not proceed. [104] Previously, MidAmerican Energy Company decided to “end its pursuit of a nuclear power plant in Payette County, Idaho.” MidAmerican cited cost as the primary factor in their decision. [105]

The federal government encouraged development through the Nuclear Power 2010 Program, which coordinates efforts for building new plants, [106] and the Energy Policy Act. [107] [108] In February 2010, President Barack Obama announced loan guarantees for two new reactors at Georgia Power’s Vogtle Electric Generating Plant. [109] [110] The reactors are “just the first of what we hope will be many new nuclear projects,” said Carol Browner, director of the White House Office of Energy and Climate Change Policy.

In February 2010, the Vermont Senate voted 26 to 4 to block operation of the Vermont Yankee Nuclear Power Plant after 2012, citing radioactive tritium leaks, misstatements in testimony by plant officials, a cooling tower collapse in 2007, and other problems. By state law, the renewal of the operating license must be approved by both houses of the legislature for the nuclear power plant to continue operation. [111]

In 2010, some companies withdrew their applications. [112] [113] In September 2010, Matthew Wald from the New York Times reported that “the nuclear renaissance is looking small and slow at the moment”. [114]

In the first quarter of 2011, renewable energy contributed 11.7 percent of total U.S. energy production (2.245 quadrillion BTUs of energy), surpassing energy production from nuclear power (2.125 quadrillion BTUs). [115] 2011 was the first year since 1997 that renewables exceeded nuclear in US total energy production. [116]

In August 2011, the TVA board of directors voted to move forward with the construction of the unit one reactor at the Bellefonte Nuclear Generating Station. [117] In addition, the Tennessee Valley Authority petitioned to restart construction on the first two units at Bellefonte. As of March 2012, many contractors had been laid off and the ultimate cost and timing for Bellefonte 1 will depend on work at another reactor TVA is completing – Watts Bar 2 in Tennessee. In February 2012, TVA said the Watts Bar 2 project was running over budget and behind schedule. [118]

The first two of the newly approved units were Units 3 and 4 at the existing Vogtle Electric Generating Plant. As of December 2011, construction by Southern Company on the two new nuclear units had begun. They were expected to be delivering commercial power by 2016 and 2017, respectively. [119] [120] One week after Southern received its license to begin major construction, a dozen groups sued to stop the expansion project, stating “public safety and environmental problems since Japan’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear reactor accident have not been taken into account”. [121] The lawsuit was dismissed in July 2012.

In 2012, The NRC approved construction permits for four new nuclear reactor units at two existing plants, the first permits in 34 years. [122] The first new permits, for two proposed reactors at the Vogtle plant, were approved in February 2012. [123] NRC Chairman Gregory Jaczko cast the lone dissenting vote, citing safety concerns stemming from Japan’s 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster: “I cannot support issuing this license as if Fukushima never happened”. [124]

| Operating reactors, building new reactors |

Also in 2012, Units 2 and 3 at the SCANA Virgil C. Summer Nuclear Generating Station in South Carolina were approved, and were scheduled to come online in 2017 and 2018, respectively. [122] After several reforecasted completion dates the project was abandoned in July 2017. [125]

Other reactors were under consideration – a third reactor at the Calvert Cliffs Nuclear Power Plant in Maryland, a third and fourth reactor at South Texas Nuclear Generating Station, together with two other reactors in Texas, four in Florida, and one in Missouri. However, these have all been postponed or canceled. [114]

In August 2012, the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia found that the NRC’s rules for the temporary storage and permanent disposal of nuclear waste stood in violation of the National Environmental Policy Act, rendering the NRC legally unable to grant final licenses. [126] This ruling was founded on the absence of a final waste repository plan.

In March 2013, the concrete for the basemat of Block 2 of the Virgil C. Summer Nuclear Generating Station was poured. First concrete for Unit 3 was completed on November 4, 2013. Construction on unit 3 of Vogtle Electric Generating Plant started that month. Unit 4 was begun in November 2013. However, following Westinghouse’s bankruptcy, the project was abandoned.

In 2015, the Energy Information Administration estimated that nuclear power’s share of U.S. generation would fall from 19% to 15% by 2040 in its central estimate (High Oil and Gas Resource case). However, as total generation increases 24% by 2040 in the central estimate, the absolute amount of nuclear generation remains fairly flat. [127]

In 2017, the US Energy Information Administration projected that US nuclear generating capacity would decline 23 percent from its 2016 level of 99.1 GW, to 76.5 GW in 2050, and the nuclear share of electrical generation to go from 20% in 2016 down to 11% in 2050. Driving the decline will be retirements of existing units, to be partially offset by additional units currently under construction and expected capacity expansions of existing reactors. [128]

The Blue Castle Project is set to begin construction near Green River, Utah in 2023. [129] The plant will use 53,500 acre-feet (66 million cubic meters) of water annually from the Green River once both reactors are commissioned. [130] The first reactor is scheduled to come online in 2028, with the second reactor coming online in 2030. [129]

On June 4, 2018, World Nuclear News reported, “President Donald Trump has directed Secretary of Energy Rick Perry to take immediate action to stop the loss of ‘fuel-secure power facilities’ from the country’s power grid, including nuclear power plants that are facing premature retirement.” [131]

On August 23, 2020, Forbes reported, that “[the 2020 Democratic Party platform] marks the first time since 1972 that the Democratic Party has said anything positive in its platform about nuclear energy”. [132]

In April 2022, the Federal government announced a $6 billion subsidy program targeting the seven plants scheduled for closure as well as others at-risk of closure, to attempt to encourage them to continue operating. [133] It will be funded by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act passed in November 2021. [133]

Nuclear power plants [ edit ]

Nuclear power plants in United States Active plants Cancelled plants Closed plants Under construction Planned plants

As of 2020, a total of 88 nuclear power plants have been built in the United States, 86 of which have had at least one operational reactor.

| Name | Unit No. |

Reactor | Status | Net capacity (MW) | Construction start | Commercial operation | Closure | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type | Model | |||||||

| Arkansas Nuclear One | first | PWR | B & W (DRY-Cont) | Operational | 836 | 1 October 1968 | 21 May 1974 | |

| 2 | PWR | What (DRY) | Operational | 988 | 6 December 1968 | 1 September 1978 | ||

| Beaver Valley | first | PWR | WH 3-loop (DRY) | Operational | 908 | 26 June 1970 | 2 July 1976 | |

| 2 | PWR | WH 3-loop (DRY) | Operational | 905 | 3 May 1974 | 14 August 1987 | ||

| Big Rock Point [134] | first | BWR | Bwr-1 | Shut down/dismantled | sixty seven | 1 May 1960 | 29 March 1963 | 29 August 1997 |

| Braidwood | first [135] | PWR | WH 4-loop (DRY) | Operational | 1194 | 1 August 1975 | 29 July 1988 | |

| 2 [136] | PWR | WH 4-loop (DRY) | Operational | 1160 | 1 August 1975 | 17 October 1988 | ||

| Browns Ferry | first | BWR | 4 (WET) | Operational | 1200 | 1 May 1967 | 1 August 1974 | |

| 2 | BWR | 4 (WET) | Operational | 1200 | 1 May 1967 | 1 March 1975 | ||

| 3 | BWR | 4 (WET) | Operational | 1210 | 1 July 1968 | 1 March 1977 | ||

| Brunswick | first | BWR | 4 (WET) | Operational | 938 | 7 February 1970 | 18 March 1977 [137] | |

| 2 | BWR | 4 (WET) | Operational | 932 | 7 February 1970 | 3 November 1975 [138] | ||

| Byron | first | PWR | WH 4-loop (DRY) | Operational | 1164 | 1 April 1975 | 16 September 1985 | |

| 2 | PWR | WH 4-loop (DRY) | Operational | 1136 | 1 April 1975 | 2 August 1987 | ||

| Callaway | first | PWR | WH 4-loop (DRY) | Operational | 1215 | 1 September 1975 | 19 December 1984 | |

| Calvert Cliffs | first | PWR | CE 2-loop (DRY) | Operational | 877 | 1 June 1968 | 8 May 1977 | |

| 2 | PWR | CE 2-loop (DRY) | Operational | 855 | 1 June 1968 | 1 April 1977 | ||

| Carbon Free Power Project [139] | first | PWR | NCALLY | Planned | 77 | (2029–2030) | ||

| 2 | PWR | NCALLY | Planned | 77 | (2029–2030) | |||

| 3 | PWR | NCALLY | Planned | 77 | (2029–2030) | |||

| 4 | PWR | NCALLY | Planned | 77 | (2029–2030) | |||

| 5 | PWR | NCALLY | Planned | 77 | (2029–2030) | |||

| 6 | PWR | NCALLY | Planned | 77 | (2029–2030) | |||

| Catawba | first | PWR | Wh 4-Loop (IceCond) | Operational | 1160 | 1 May 1974 | 29 June 1985 | |

| 2 | PWR | Wh 4-Loop (IceCond) | Operational | 1150 | 1 May 1974 | 19 August 1986 | ||

| Clinch River | first | BWR | BURX-300 | Planned | 180 | |||

| Clinton | first | BWR | Bur-6 (wet) | Operational | 1062 | 1 October 1975 | 24 November 1987 | |

| Columbia | first | BWR | Pur-5 (WET) | Operational | 1131 | 1 August 1972 | 13 December 1984 | |

| Comanche Peak | first | PWR | WH 4-loop (DRY) | Operational | 1205 | 19 December 1974 | 13 August 1990 | |

| 2 | PWR | WH 4-loop (DRY) | Operational | 1195 | 19 December 1974 | 3 August 1993 | ||

| Connecticut Yankee | first | PWR | WH (DRY) | Shut down/dismantled | 582 | 1 May 1964 | 1 January 1968 | 5 December 1996 |

| Cooper | first | BWR | 4 (WET) | Operational | 769 | 1 June 1968 | 1 July 1974 | |

| Crystal River 3 | first | PWR | B & W (DRY) | Shut down | 860 | 25 September 1968 | 13 March 1977 | 5 February 2013 |

| Davis-boss | first | PWR | B & W (DRY) | Operational | 894 | 1 September 1970 | 31 July 1978 | |

| Diablo Canyon | first | PWR | WH 4-Loop (DRY) | Operational | 1138 | 23 April 1968 | 7 May 1985 | |

| 2 | PWR | WH 4-Loop (DRY) | Operational | 1118 | 9 December 1970 | 13 March 1986 | ||

| Donald C. Cook | first | PWR | Wh 4-Loop (IceCond) | Operational | 1020 | 25 March 1969 | 27 August 1975 | |

| 2 | PWR | Wh 4-Loop (IceCond) | Operational | 1090 | 25 March 1969 | 1 July 1978 | ||

| Dresden | first | BWR | Bwr-1 | Shut down | 197 | 1 May 1956 | 4 July 1960 | 31 October 1978 |

| 2 | BWR | Burf-3 (WET) | Operational | 894 | 10 January 1966 | 9 June 1970 | ||

| 3 | BWR | Burf-3 (WET) | Operational | 879 | 14 October 1966 | 16 November 1971 | ||

| Duane Arnold | first | BWR | 4 (WET) | Shut down | 601 | 22 May 1970 | 1 February 1975 | 10 August 2020 |

| Edwin I. Hatch | first | BWR | 4 (WET) | Operational | 924 | 30 September 1968 | 31 December 1975 | |

| 2 | BWR | 4 (WET) | Operational | 924 | 1 February 1972 | 5 September 1979 | ||

| Elke River | first | BWR | Shut down/dismantled | 22 | 1 January 1959 | 1 July 1964 | 1 February 1968 | |

| Fermi | first | FBR | Prototype | Shut down | sixty one | 8 August 1956 | 7 August 1966 | 29 November 1972 |

| 2 | BWR | 4 (WET) | Operational | 1115 | 26 September 1972 | 23 January 1988 | ||

| 3 | BWR | Euphon | Planned | 1600 | ||||

| Fort Calhoun | first | PWR | CE 2-loop (WET) | Shut down | 482 | 7 June 1968 | 9 August 1973 | 24 October 2016 |

| Fort St. Vrain | first | HTGR | General Atomics | Shut down | 330 | 1 September 1968 | 1 July 1979 | 29 August 1989 |

| Ass | first | PWR | WH 2-loop (DRY) | Operational | 560 | 25 April 1966 | 1 June 1970 | |

| Grand Gulf | first | BWR | Bur-6 (wet) | Operational | 1401 | 4 May 1974 | 1 July 1985 | |

| H. B. Robinson | first | PWR | WH 3-loop (DRY) | Operational | 735 | 13 April 1967 | 7 March 1971 | |

| Hallam | first | SGR | Atomics International | Shut down/dismantled | 75 | 1 January 1959 | 1 November 1963 | 1 September 1969 |

| Hope Creek | first | BWR | 4 (WET) | Operational | 1172 | 1 March 1976 | 20 December 1986 | |

| Humboldt Bay | first | BWR | Bwr-1 | Shut down/dismantled | 63 | 1 November 1960 | first August 1963 | 2 July 1976 |

| Indian Point | first | PWR | Shut down | 257 | 1 May 1956 | 1 October 1962 | 31 October 1974 | |

| 2 | PWR | WH 4-loop (DRY) | Shut down | 998 | 14 October 1966 | 1 August 1974 | 30 April 2020 [140] | |

| 3 | PWR | WH 4-loop (DRY) | Shut down | 1030 | 1 November 1968 | 30 August 1976 | 30 April 2021 [140] | |

| James A. FitzPatrick | first | BWR | 4 (WET) | Operational | 813 | 1 September 1968 | 28 July 1975 | |

| Joseph M. Farley | first | PWR | WH 3-Loop (DRY) | Operational | 874 | 1 October 1970 | 1 December 1977 | |

| 2 | PWR | WH 3-Loop (DRY) | Operational | 883 | 1 October 1970 | 30 July 1981 | ||

| Kawaunchee | first | PWR | WH 2-loop (DRY) | Shut down | 566 | 6 August 1968 | 16 June 1974 | 7 May 2013 |

| The Crosse | first | BWR | Bwr-1 | Shut down/dismantled | 48 | 1 March 1963 | 7 November 1969 | 30 April 1987 |

| LaSalle County | first | BWR | Pur-5 (WET) | Operational | 1137 | 10 September 1973 | 1 January 1984 | |

| 2 | BWR | Pur-5 (WET) | Operational | 1140 | 10 September 1973 | 19 October 1984 | ||

| Limerick | first | BWR | Pur-5 (WET) | Operational | 1134 | 19 June 1974 | 1 February 1986 | |

| 2 | BWR | Pur-5 (WET) | Operational | 1134 | 19 June 1974 | 8 January 1990 | ||

| Maine Yankee | first | PWR | WH (DRY) | Shut down/dismantled | 860 | 1 October 1968 | 28 December 1972 | 1 August 1997 |

| McGuire | first | PWR | Wh 4-Loop (IceCond) | Operational | 1158 | 1 April 1971 | 1 December 1981 | |

| 2 | PWR | Wh 4-Loop (IceCond) | Operational | 1158 | 1 April 1971 | 1 March 1984 | ||

| Millstone | first | BWR | Burf-3 (WET) | Shut down | 641 | 1 May 1966 | 28 December 1970 | 21 July 1998 |

| 2 | PWR | CE 2-loop (DRY) | Operational | 869 | 1 November 1969 | 26 December 1975 | ||

| 3 | PWR | WH 4-Loop (DRY) | Operational | 1210 | 9 August 1974 | 23 April 1986 | ||

| Monticello | first | BWR | Burf-3 (WET) | Operational | 628 | 19 June 1967 | 30 June 1971 | |

| Naughton | first | SFR | Sodium | Planned | 345 | |||

| Nine Mile Point | first | BWR | Burf-2 (WET) | Operational | 613 | 12 April 1965 | 1 December 1969 | |

| 2 | BWR | Pur-5 (WET) | Operational | 1277 | 1 August 1975 | 11 March 1988 | ||

| North Anna | first | PWR | WH 3-Loop (DRY) | Operational | 948 | 19 February 1971 | 6 June 1978 | |

| 2 | PWR | WH 3-Loop (DRY) | Operational | 944 | 19 February 1971 | 14 December 1980 | ||

| 3 | BWR | Euphon | Planned | 1500 | ||||

| Oconee | first | PWR | B & W (DRY) | Operational | 847 | 6 November 1967 | 15 July 1973 | |

| 2 | PWR | B & W (DRY) | Operational | 848 | 6 November 1967 | 9 September 1974 | ||

| 3 | PWR | B & W (DRY) | Operational | 859 | 6 November 1967 | 16 December 1974 | ||

| Oyster Creek | first | BWR | Burf-2 (WET) | Shut down | 619 | 15 December 1964 | 23 December 1969 | 17 September 2018 |

| Palisades | first | PWR | CE 2-loop (DRY) | Shut down | 805 | 14 March 1967 | 31 December 1971 | 20 May 2022 |

| Green pole | first | PWR | CE80 2-loop (DRY) | Operational | 1311 | 25 May 1976 | 28 January 1986 | |

| 2 | PWR | CE80 2-loop (DRY) | Operational | 1314 | 1 June 1976 | 19 September 1986 | ||

| 3 | PWR | CE80 2-loop (DRY) | Operational | 1312 | 1 June 1976 | 8 January 1988 | ||

| Parr | first | Pierce | CVTR | Shut down/dismantled | 17 | 1 January 1960 | 18 December 1963 | 10 January 1967 |

| Pathfinder | first | BWR | Bwr-1 | Shut down/dismantled | 59 | 1 January 1959 | 1 August 1966 | 1 October 1967 |

| Peach Bottom | first | GCR | Prototype | Shut down | 40 | 1 February 1962 | 1 June 1966 | 1 November 1974 |

| 2 | BWR | 4 (WET) | Operational | 1300 | 31 January 1968 | 5 July 1974 | ||

| 3 | BWR | 4 (WET) | Operational | 1331 | 31 January 1968 | 23 December 1974 | ||

| Perry | first | BWR | Bur-6 (wet) | Operational | 1240 | 1 October 1974 | 18 November 1987 | |

| Pilgrim | first | BWR | Burf-3 (WET) | Shut down | 677 | 26 August 1968 | 9 December 1972 | 31 May 2019 |

| Piqua | first | OCR | Atomics International | Decommissioned | twelfth | 1 January 1960 | 1 November 1963 | 1 January 1966 |

| Point Beach | first | PWR | WH 2-loop (DRY) | Operational | 591 | 19 July 1967 | 21 December 1970 | |

| 2 | PWR | WH 2-loop (DRY) | Operational | 591 | 25 July 1968 | 1 October 1972 | ||

| Prairie Island | first | PWR | WH 2-loop (DRY) | Operational | 522 | 25 June 1968 | 16 December 1973 | |

| 2 | PWR | WH 2-loop (DRY) | Operational | 519 | 25 June 1969 | 21 December 1974 | ||

| Quad Cities | first | BWR | 4 (WET) | Operational | 908 | 15 February 1967 | 18 February 1973 | |

| 2 | BWR | 4 (WET) | Operational | 911 | 15 February 1967 | 10 March 1973 | ||

| Rancho Seco | first | PWR | WH (DRY) | Decommissioned | 873 | 1 April 1969 | 17 April 1975 | 23 October 2009 |

| River Bend | first | BWR | Bur-6 (wet) | Operational | 967 | 25 March 1977 | 16 June 1986 | |

| Salem | first | PWR | WH 4-loop (DRY) | Operational | 1169 | 25 September 1968 | 30 June 1977 | |

| 2 | PWR | WH 4-loop (DRY) | Operational | 1158 | 25 September 1968 | 31 October 1981 | ||

| San Onofre | first | PWR | WH (DRY) | Shut down/dismantled | 436 | 16 July 1964 | 1 January 1968 | 30 November 1992 |

| 2 | PWR | What (DRY) | Shut down | 1070 | 1 March 1974 | 8 August 1983 | 7 June 2013 | |

| 3 | PWR | What (DRY) | Shut down | 1180 | 1 March 1974 | 1 April 1984 | 7 June 2013 | |

| Saxton | first | PWR | Decommissioned | 3 | 1 January 1960 | November 1961 | May 1972 | |

| Seabrook Station | first | PWR | WH 4-Loop (DRY) | Operational | 1246 | 7 July 1976 | 15 March 1990 | |

| Sequoyah | first | PWR | Wh 4-Loop (IceCond) | Operational | 1152 | 27 May 1970 | 1 July 1981 | |

| 2 | PWR | Wh 4-Loop (IceCond) | Operational | 1139 | 27 May 1970 | 1 June 1982 | ||

| Shearon Harris | first | PWR | WH 3-Loop (DRY) | Operational | 964 | 28 January 1978 | 2 May 1987 | |

| Shippingport | first | PWR | WH | Shut down/dismantled | 60 | 6 September 1954 | 26 May 1958 | December 1989 |

| Shoreham | first | BWR | GE | Shut down | 820 | 1 November 1972 | 1 August 1986 | 1 May 1989 |

| SRE | first | FBR | Decommissioned | 6.5 | 1954 | 12 July 1957 | 15 February 1964 | |

| South Texas | first | PWR | WH 4-loop (DRY) | Operational | 1280 | 22 December 1975 | 25 August 1988 | |

| 2 | PWR | WH 4-loop (DRY) | Operational | 1280 | 22 December 1975 | 19 June 1989 | ||

| St. Lucie | first | PWR | What (DRY) | Operational | 981 | 1 July 1970 | 1 March 1976 | |

| 2 | PWR | What (DRY) | Operational | 987 | 2 June 1977 | 10 June 1983 | ||

| Surry | first | PWR | WH 3-loop (DRY) | Operational | 838 | 25 June 1968 | 22 December 1972 | |

| 2 | PWR | WH 3-loop (DRY) | Operational | 838 | 25 June 1968 | 1 May 1973 | ||

| Susquehanna | first | BWR | Pur-5 (WET) | Operational | 1257 | 2 November 1973 | 12 November 1982 | |

| 2 | BWR | Pur-5 (WET) | Operational | 1257 | 2 November 1973 | 27 June 1984 | ||

| Three Mile Island | first | PWR | B & W (DRY) | Shut down | 819 | 18 May 1968 | 2 September 1974 | 20 September 2019 |

| 2 | PWR | B & W (DRY) | Core melt | 880 | 1 November 1969 | 30 December 1978 | 1979 | |

| Trojan | first | PWR | WH (DRY) | Shut down/dismantled | 1095 | 1 February 1970 | 20 May 1976 | 1992 |

| Turkey Point | first | PWR | WH 3-loop (DRY) | Operational | 837 | 27 April 1967 | 14 December 1972 | |

| 2 | PWR | WH 3-loop (DRY) | Operational | 821 | 27 April 1967 | 7 September 1973 | ||

| 3 | PWR | AP1000 | Planned | 1100 | ||||

| 4 | PWR | AP1000 | Planned | 1100 | ||||

| Vallecitos | first | BWR | Bwr-1 | Shut down | 25 | 1 January 1956 | 19 October 1957 | 9 December 1963 |

| Vermont Yankee | first | BWR | 4 (WET) | Shut down | 605 [141] | 11 December 1967 | 30 November 1972 | 29 December 2014 [142] |

| Virgil C. Summer | first | PWR | WH 3-Loop (DRY) | Operational | 1000 | 21 March 1973 | 1 January 1984 | |

| Vogtle | first | PWR | WH 4-Loop (DRY) | Operational | 1150 | 1 August 1976 | 1 June 1987 | |

| 2 | PWR | WH 4-Loop (DRY) | Operational | 1152 | 1 August 1976 | 20 May 1989 | ||

| 3 | PWR | AP1000 | Under commissioning | 1117 | 12 March 2013 | ( 2023 ) [143] | ||

| 4 | PWR | AP1000 | Under construction | 1117 | 19 November 2013 | ( 2023 ) [143] | ||

| Waterford | first | PWR | CE 2-loop (DRY) | Operational | 1168 | 14 November 1974 | 24 September 1985 | |

| Watts Bar | first | PWR | Wh 4-Loop (IceCond) | Operational | 1157 | 20 July 1973 | 27 May 1996 | |

| 2 | PWR | Wh 4-Loop (IceCond) | Operational | 1164 | 1 September 1973 | 4 June 2016 | ||

| Wolf Creek | first | PWR | WH 4-Loop (DRY) | Operational | 1200 | 31 May 1977 | 3 September 1985 | |

| Yankee Rowe | first | PWR | WH (DRY) | Shut down/dismantled | 167 | 1 November 1957 | 1 July 1961 | 1 October 1991 |

| Zion | first | PWR | WH (DRY) | Shut down/dismantled | 1040 | 1 December 1968 | 31 December 1973 | 13 February 1998 |

| 2 | PWR | WH (DRY) | Shut down/dismantled | 1040 | 1 December 1968 | 17 September 1974 | 13 February 1998 | |

In 2019 the NRC approved a second 20-year licence extension for Turkey Point units 3 and 4, the first time NRC had extended licences to 80 years total lifetime. Similar extensions for about 20 reactors are planned or intended, with more expected in the future. [144]

Safety and accidents [ edit ]

Regulation of nuclear power plants in the United States is conducted by the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, which divides the nation into 4 administrative divisions.

Three Mile Island [ edit ]

On March 28, 1979, equipment failures and operator error contributed to loss of coolant and a partial core meltdown at the Three Mile Island Nuclear Power Plant in Pennsylvania. The mechanical failures were compounded by the initial failure of plant operators to recognize the situation as a loss-of-coolant accident due to inadequate training and human factors, such as human-computer interaction design oversights relating to ambiguous control room indicators in the power plant’s user interface. [145] The scope and complexity of the accident became clear over the course of five days, as employees of Met Ed, Pennsylvania state officials, and members of the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) tried to understand the problem, communicate the situation to the press and local community, decide whether the accident required an emergency evacuation, and ultimately end the crisis. The NRC’s authorization of the release of 40,000 gallons of radioactive waste water directly in the Susquehanna River led to a loss of credibility with the press and community. [145]

The Three Mile Island accident inspired Perrow’s book Normal Accidents , where a nuclear accident occurs, resulting from an unanticipated interaction of multiple failures in a complex system. TMI was an example of a normal accident because it was “unexpected, incomprehensible, uncontrollable and unavoidable”. [146] The World Nuclear Association has stated that cleanup of the damaged nuclear reactor system at TMI-2 took nearly 12 years and cost approximately US$973 million. [147] Benjamin K. Sovacool, in his 2007 preliminary assessment of major energy accidents, estimated that the TMI accident caused a total of $2.4 billion in property damages. [148] The health effects of the Three Mile Island accident are widely, but not universally, agreed to be very low level. [147] [149] The accident triggered protests around the world. [150]

The 1979 Three Mile Island accident was a pivotal event that led to questions about U.S. nuclear safety. [151] Earlier events had a similar effect, including a 1975 fire at Browns Ferry and the 1976 testimonials of three concerned GE nuclear engineers, the GE Three. In 1981, workers inadvertently reversed pipe restraints at the Diablo Canyon Power Plant reactors, compromising seismic protection systems, which further undermined confidence in nuclear safety. All of these well-publicised events undermined public support for the U.S. nuclear industry in the 1970s and the 1980s. [151]

Other incidents [ edit ]

On March 5, 2002, maintenance workers discovered that corrosion had eaten a football-sized hole into the reactor vessel head of the Davis-Besse plant. Although the corrosion did not lead to an accident, this was considered to be a serious nuclear safety incident. [152] [153] The Nuclear Regulatory Commission kept Davis-Besse shut down until March 2004, so that FirstEnergy was able to perform all the necessary maintenance for safe operations. The NRC imposed its largest fine ever—more than $5 million—against FirstEnergy for the actions that led to the corrosion. The company paid an additional $28 million in fines under a settlement with the U.S. Department of Justice. [152]

In 2013 the San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station was permanently retired when premature wear was found in the Steam Generators which had been replaced in 2010–2011.

The nuclear industry in the United States has maintained one of the best industrial safety records in the world with respect to all kinds of accidents. For 2008, the industry hit a new low of 0.13 industrial accidents per 200,000 worker-hours. [154] This is improved over 0.24 in 2005, which was still a factor of 14.6 less than the 3.5 number for all manufacturing industries. [155] However, more than a quarter of U.S. nuclear plant operators “have failed to properly tell regulators about equipment defects that could imperil reactor safety”, according to a Nuclear Regulatory Commission report. [156]

As of February 2009, the NRC requires that the design of new power plants ensures that the reactor containment would remain intact, cooling systems would continue to operate, and spent fuel pools would be protected, in the event of an aircraft crash. This is an issue that has gained attention since the September 11 attacks. The regulation does not apply to the 100 commercial reactors now operating. [157] However, the containment structures of nuclear power plants are among the strongest structures ever built by mankind; independent studies have shown that existing plants would easily survive the impact of a large commercial jetliner without loss of structural integrity. [158]

Recent concerns have been expressed about safety issues affecting a large part of the nuclear fleet of reactors. In 2012, the Union of Concerned Scientists, which tracks ongoing safety issues at operating nuclear plants, found that “leakage of radioactive materials is a pervasive problem at almost 90 percent of all reactors, as are issues that pose a risk of nuclear accidents”. [159] The U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission reports that radioactive tritium has leaked from 48 of the 65 nuclear sites in the United States. [160]

Post-Fukushima concerns [ edit ]

Following the Japanese Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, according to Black & Veatch’s annual utility survey that took place after the disaster, of the 700 executives from the US electric utility industry that were surveyed, nuclear safety was the top concern. [161] There are likely to be increased requirements for on-site spent fuel management and elevated design basis threats at nuclear power plants. [77] [78] License extensions for existing reactors will face additional scrutiny, with outcomes depending on the degree to which plants can meet new requirements, and some extensions already granted for more than 60 of the 104 operating U.S. reactors could be revisited. On-site storage, consolidated long-term storage, and geological disposal of spent fuel is “likely to be reevaluated in a new light because of the Fukushima storage pool experience”. [77] In March 2011, nuclear experts told Congress that spent-fuel pools at US nuclear power plants are too full. They say the entire US spent-fuel policy should be overhauled in light of the Fukushima I nuclear accidents. [162]

David Lochbaum, chief nuclear safety officer with the Union of Concerned Scientists, has repeatedly questioned the safety of the Fukushima I Plant’s General Electric Mark 1 reactor design, which is used in almost a quarter of the United States’ nuclear fleet. [163]

About one third of reactors in the US are boiling water reactors, the same technology which was involved in the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. There are also eight nuclear power plants located along the seismically active West coast. Twelve of the American reactors that are of the same vintage as the Fukushima Daiichi plant are in seismically active areas. [164] Earthquake risk is often measured by “Peak Ground Acceleration”, or PGA, and the following nuclear power plants have a two percent or greater chance of having PGA over 0.15g in the next 50 years: Diablo Canyon, Calif.; San Onofre, Calif.; Sequoyah, Tenn.; H.B. Robinson, SC.; Watts Bar, Tenn.; Virgil C. Summer, SC.; Vogtle, GA.; Indian Point, NY.; Oconee, SC.; and Seabrook, NH. Most nuclear plants are designed to keep operating up to 0.2g, but can withstand PGA much higher than 0.2. [164]

| Date | Plant | Location | Description | Cost (in millions $ 2006) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| March 28, 1979 | Three Mile Island | Londonderry Township, Pennsylvania | Loss of coolant and partial core meltdown, see Three Mile Island accident and Three Mile Island accident health effects | |

| March 9, 1985 | Browns Ferry | Athens, Alabama | Instrumentation systems malfunction during startup, which led to suspension of operations at all three Units | |

| April 11, 1986 | Pilgrim | Plymouth, Massachusetts | Recurring equipment problems force emergency shutdown of Boston Edison’s plant | |

| March 31, 1987 | Peach Bottom | Delta, Pennsylvania | Units 2 and 3 shutdown due to cooling malfunctions and unexplained equipment problems | |

| December 19, 1987 | Nine Mile Point | Scriba, New York | Malfunctions force Niagara Mohawk Power Corporation to shut down Unit 1 | |

| February 20, 1996 | Millstone | Waterford, Connecticut | Leaking valve forces shutdown of Units 1 and 2, multiple equipment failures found | |

| September 2, 1996 | Crystal River | Crystal River, Florida | Balance-of-plant equipment malfunction forces shutdown and extensive repairs | |

| February 1, 2010 | Vermont Yankee | Vernon, Vermont | Deteriorating underground pipes leak radioactive tritium into groundwater supplies |

Security and deliberate attacks [ edit ]

The United States 9/11 Commission has said that nuclear power plants were potential targets originally considered for the September 11, 2001 attacks. If terrorist groups could sufficiently damage safety systems to cause a core meltdown at a nuclear power plant, and/or sufficiently damage spent fuel pools, such an attack could lead to widespread radioactive contamination. The research scientist Harold Feiveson has written that nuclear facilities should be made extremely safe from attacks that could release massive quantities of radioactivity into the community. New reactor designs have features of passive nuclear safety, which may help. In the United States, the NRC carries out “Force on Force” (FOF) exercises at all Nuclear Power Plant (NPP) sites at least once every three years. [47]

Uranium supply [ edit ]

A 2012 report by the International Atomic Energy Agency concluded: “The currently defined uranium resource base is more than adequate to meet high-case requirements through 2035 and well into the foreseeable future.” [167]

At the start of 2013, the identified remaining worldwide uranium resources stood at 5.90 million tons, enough to supply the world’s reactors at current consumption rates for more than 120 years, even if no additional uranium deposits are discovered in the meantime. Undiscovered uranium resources as of 2013 were estimated to be 7.7 million tons. Doubling the price of uranium would increase the identified reserves as of 2013 to 7.64 million tons. [168] Over the decade 2003–2013, the identified reserves of uranium (at the same price of US$130/kg) rose from 4.59 million tons in 2003 to 5.90 million tons in 2013, an increase of 28%. [169]

Fuel cycle [ edit ]

Uranium mining [ edit ]

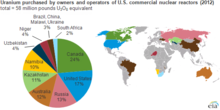

The United States has the 4th largest uranium reserves in the world. [170] The U.S. has its most prominent uranium reserves in New Mexico, Texas, and Wyoming. The U.S. Department of Energy has approximated there to be at least 300 million pounds of uranium in these areas. [171] Domestic production increased until 1980, after which it declined sharply due to low uranium prices. In 2012, the United States mined 17% of the uranium consumed by its nuclear power plants. The remainder was imported, principally from Canada, Russia and Australia. [170] Uranium is mined using several methods including open-pit mining, underground mining, and in-situ leaching. [172] As of 2017, there are more than 4000 abandoned uranium mines in the western USA, with 520 to over 1000 on Navajo land, and many others being located on other tribal lands. [43] [173]

Uranium enrichment [ edit ]

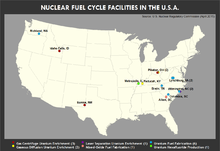

There is one gas centrifuge enrichment plant currently in commercial operation in the US. The National Enrichment Facility, operated by URENCO east of Eunice, New Mexico, was the first uranium enrichment plant in 30 years to be built in the US. The plant started enriching uranium in 2010. [174] Two additional gas centrifuge plants have been licensed by the NRC, but are not operating. The American Centrifuge Plant in Piketown, Ohio broke ground in 2007, but stopped construction in 2009. The Eagle Rock Enrichment Facility in Bonneville County, Idaho was licensed in 2011, but construction is on hold. [175]

Previously (2008), demonstration activities were underway in Oak Ridge, Tennessee for a future centrifugal enrichment plant. The new plant would have been called the American Centrifuge Plant, at an estimated cost of US$2.3 billion. [176]

As of September 30, 2015, the DOE is ending its contract with the American Centrifuge Project and has stopped funding the project. [177]

Reprocessing [ edit ]

Nuclear reprocessing has been politically controversial because of the alleged potential to contribute to nuclear proliferation, the alleged vulnerability to nuclear terrorism, the debate over whether and where to dispose of spent fuel in a deep geological repository, and because of disputes about its economics compared to the once-through fuel cycle. [178] The Obama administration has disallowed reprocessing of spent fuel, citing nuclear proliferation concerns. [179] Opponents of reprocessing contend that the recycled materials could be used for weapons. However, it is unlikely that reprocessed plutonium or other material extracted from commercial spent fuel would be used for nuclear weapons, because it is not weapons-grade material. [180] Nonetheless, according to the Union of Concerned Scientists, it is possible that terrorists could steal these materials, because the reprocessed plutonium is less radiotoxic than spent fuel and therefore much easier to handle. [181] Additionally, it has been argued that reprocessing is more expensive when compared with spent fuel storage. One study by the Boston Consulting Group estimated that reprocessing is six percent more expensive than spent fuel storage while another study by the Kennedy School of Government stated that reprocessing is 100 percent more expensive. [182] Those two data points alone can serve to indicate that calculations as to the cost of nuclear reprocessing and the production of MOX-fuel compared to the “once thru fuel cycle” and disposal in deep geological repository are extremely difficult and results tend to vary widely even among dispassionate expert observers – let alone those whose results are colored by a political or economic agenda. Furthermore, fluctuations on the uranium market can make usage of MOX-fuel or even re-enrichment of reprocessed uranium more or less economical depending on long term price trends.

Waste disposal [ edit ]

Recently, as plants continue to age, many on-site spent fuel pools have come near capacity, prompting creation of dry cask storage facilities as well. Several lawsuits between utilities and the government have transpired over the cost of these facilities, because by law the government is required to foot the bill for actions that go beyond the spent fuel pool.

There are some 65,000 tons of nuclear waste now in temporary storage throughout the U.S. [183] Since 1987, Yucca Mountain, in Nevada, had been the proposed site for the Yucca Mountain nuclear waste repository, but the project was shelved in 2009 following years of controversy and legal wrangling. [183] [184] Yucca Mountain is on Native American land and is considered sacred. Native Americans have not consented to having any nuclear waste plants placed in this area. [forty six] An alternative plan has not been proffered. [185] In June 2018, the Trump administration and some members of Congress again began proposing using Yucca Mountain, with Nevada Senators raising opposition. [186]

At places like Maine Yankee, Connecticut Yankee and Rancho Seco, reactors no longer operate, but the spent fuel remains in small concrete-and-steel silos that require maintenance and monitoring by a guard force. Sometimes the presence of nuclear waste prevents re-use of the sites by industry. [187]

Without a long-term solution to store nuclear waste, a nuclear renaissance in the U.S. remains unlikely. Nine states have “explicit moratoria on new nuclear power until a storage solution emerges”. [188] [189]

Some nuclear power advocates argue that the United States should develop factories and reactors that will recycle some spent fuel. But the Blue Ribbon Commission on America’s Nuclear Future said in 2012 that “no existing technology was adequate for that purpose, given cost considerations and the risk of nuclear proliferation”. [189] A major recommendation was that “the United States should undertake…one or more permanent deep geological facilities for the safe disposal of spent fuel and high-level nuclear waste”. [190]

There is an “international consensus on the advisability of storing nuclear waste in deep underground repositories”, [191] but no country in the world has yet opened such a site. [191] [101] [192] [193] [194] [195] The Obama administration has disallowed reprocessing of nuclear waste, citing nuclear proliferation concerns. [179]

The U.S Nuclear Waste Policy Act, a fund which previously received $750 million in fee revenues each year from the nation’s combined nuclear electric utilities, had an unspent balance of $44.5 billion as of the end of FY2017, when a court ordered the federal government to cease withdrawing the fund, until it provides a destination for the utilities commercial spent fuel. [196]

Horizontal drillhole disposal describes proposals to drill over one kilometer vertically, and two kilometers horizontally in the earth’s crust, for the purpose of disposing of high-level waste forms such as spent nuclear fuel, Caesium-137, or Strontium-90. After the emplacement and the retrievability period, [ clarification needed ] drillholes would be backfilled and sealed. A series of tests of the technology were carried out in November 2018 and then again publicly in January 2019 by a U.S. based private company. [197] The test demonstrated the emplacement of a test-canister in a horizontal drillhole and retrieval of the same canister. There was no actual high-level waste used in this test. [198] [199]

Water use in nuclear power production [ edit ]

A 2011 NREL study of water use in electricity generation concluded that the median nuclear plant with cooling towers consumed 672 gallons per megawatt-hour (gal/MWh), a usage similar to that of coal plants, but more than other generating technologies, except hydroelectricity (median reservoir evaporation loss of 4,491 gal/MWh) and concentrating solar power (786 gal/MWh for power tower designs, and 865 for trough). Nuclear plants with once-through cooling systems consume only 269 gal/MWh, but require withdrawal of 44,350 gal/MWh. This makes nuclear plants with once-through cooling susceptible to drought. [201]

Once-through cooling systems, while once common, have come under attack for the possibility of damage to the environment. Wildlife can become trapped inside the cooling systems and killed, and the increased water temperature of the returning water can impact local ecosystems. US EPA regulations favors recirculating systems, even forcing some older power plants to replace existing once-through cooling systems with new recirculating systems. [ citation needed ]

A 2008 study by the Associated Press found that of the 104 nuclear reactors in the U.S., “… 24 are in areas experiencing the most severe levels of drought. All but two are built on the shores of lakes and rivers and rely on submerged intake pipes to draw billions of gallons of water for use in cooling and condensing steam after it has turned the plants’ turbines,” [202] much like all Rankine cycle power plants. During the 2008 southeast drought, reactor output was reduced to lower operating power or forced to shut down for safety. [202]

The Palo Verde Nuclear Generating Station is located in a desert and purchases reclaimed wastewater for cooling. [203]

Plant decommissioning [ edit ]

The price of energy inputs and the environmental costs of every nuclear power plant continue long after the facility has finished generating its last useful electricity. Both nuclear reactors and uranium enrichment facilities must be decommissioned, returning the facility and its parts to a safe enough level to be entrusted for other uses. After a cooling-off period that may last as long as a century, reactors must be dismantled and cut into small pieces to be packed in containers for final disposal. The process is very expensive, time-consuming, dangerous for workers, hazardous to the natural environment, and presents new opportunities for human error, accidents or sabotage. [204]

The total energy required for decommissioning can be as much as 50% more than the energy needed for the original construction. In most cases, the decommissioning process costs between US$300 million to US$5.6 billion. Decommissioning at nuclear sites which have experienced a serious accident are the most expensive and time-consuming. In the U.S. there are 13 reactors that have permanently shut down and are in some phase of decommissioning, but none of them have completed the process. [204]

New methods for decommissioning have been developed in order to minimize the usual high decommissioning costs. One of these methods is in situ decommissioning (ISD), which was implemented at the U.S. Department of Energy Savannah River Site in South Carolina for the closures of the P and R Reactors. With this tactic, the cost of decommissioning both reactors was $73 million. In comparison, the decommissioning of each reactor using traditional methods would have been an estimated $250 million. This results in a 71% decrease in cost by using ISD. [205]

In the United States a Nuclear Waste Policy Act and Nuclear Decommissioning Trust Fund is legally required, with utilities banking 0.1 to 0.2 cents/kWh during operations to fund future decommissioning. They must report regularly to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) on the status of their decommissioning funds. About 70% of the total estimated cost of decommissioning all U.S. nuclear power reactors has already been collected (on the basis of the average cost of $320 million per reactor-steam turbine unit). [206] As of 2011, there are 13 reactors that had permanently shut down and are in some phase of decommissioning. [204] With Connecticut Yankee Nuclear Power Plant and Yankee Rowe Nuclear Power Station having completed the process in 2006–2007, after ceasing commercial electricity production circa 1992.

The majority of the 15 years, was used to allow the station to naturally cool-down on its own, which makes the manual disassembly process both safer and cheaper.

The number of nuclear power reactors are shrinking as they near the end of their life.

It is expected that by 2025 many of the reactors will have been shut down due to their age.

Because the costs associated with the constructions of nuclear reactors are also continuously increasing, this is expected to be problematic for the provision of energy in the country. [207] When reactors are shut down, stakeholders in the energy sector have often not replaced them with renewable energy resources but rather with coal or natural gas.

This is because unlike renewable energy sources such as wind and solar, coal and natural gas can be used to generate electricity on a 24-hour basis. [208]

Organizations [ edit ]

Fuel Sards [ edit ]

The following companies have active Nuclear fuel fabrication facilities in the United States. [209] These are all light water fuel fabrication facilities because only LWRs are operating in the US. The US currently has no MOX fuel fabrication facilities, though Duke Energy has expressed intent of building one of a relatively small capacity. [210]

-

- Framatome (formerly Areva) runs fabrication facilities in Lynchburg, Virginia and Richland, Washington. It also has a Generation III+ plant design, EPR (formerly the Evolutionary Power Reactor), which it plans to market in the US. [211]

-

- Westinghouse operates a fuel fabrication facility in Columbia, South Carolina, [212] which processes 1,600 metric tons Uranium (MTU) per year. It previously operated a nuclear fuel plant in Hematite, Missouri but has since closed it down.

-

- GE pioneered the BWR technology that has become widely used throughout the world. It formed the Global Nuclear Fuel joint venture in 1999 with Hitachi and Toshiba and later restructured into GE-Hitachi Nuclear Energy . It operates the fuel fabrication facility in Wilmington, North Carolina, with a capacity of 1,200 MTU per year.

-

- KazAtomProm and the US company Centrus Energy have a partnership on competitive supplies of Kazakhstan’s uranium to the US market. [213]

Industry and academic [ edit ]

The American Nuclear Society (ANS) scientific and educational organization has both academic and industry members. The organization publishes a large amount of literature on nuclear technology in several journals. The ANS also has some offshoot organizations such as North American Young Generation in Nuclear (NA-YGN).