Quanzhou -wikipedia

Prefecture-level city in Fujian, People’s Republic of China

|

Quanzhou Quanzhou |

|

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

| Coordinates (Quanzhou municipal government): 24°52′28″N 118 ° 40′33 ″ and / 24,8744 ° n 118,6757 ° e Coordinates: 24°52′28″N 118°40′33″E/ 24,8744 ° n 118,6757 ° e | |

| Country | People’s Republic of China |

| Province | Fujian |

| Municipal seat | Fengze district |

| • CPC Secretary | Kang Tao |

| • Mayor | Wang Yongli |

| • Prefecture-level city | 11,218.91 km 2 (4,331.65 sq mi) |

| • Urban | 872.4 km 2 (336.8 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 4,274.5 km 2 (1,650.4 sq mi) |

| • Prefecture-level city | 8,782,285 |

| • Density | 780/km 2 (2,000/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 1,728,386 |

| • Urban density | 2,000/km 2 (5,100/sq mi) |

| • Metro | 6,669,711 |

| • Metro density | 1,600/km 2 (4,000/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+8 (CST) |

| Postal code |

362000 |

| Area code | 0595 |

| ISO 3166 code | CN-FJ-05 |

| GDP | 2019 [2] |

| – Total | CNY 994.666 billion |

| – to happen | CNY 114,067 (US$16,535) |

| – Growth | |

| License Plate Prefixes | Fujian C |

| Local Dialect | HOKKIEN/MIN NAN: Quanzhou Dialect |

| Website | www |

| Chinese | Quanzhou |

| Hockey boys | Choan-chiu |

| Postal | Chinchew |

| Literal meaning | “Spring Prefecture” |

| Official name | Quanzhou: Emporium of the World in Song-Yuan China |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iv |

| Designated | 2021 (44th session) |

| Reference no. | 1561 |

| Region | List of World Heritage Sites in China |

Quanzhou , alternatively known as Chinchew , is a prefecture-level port city on the north bank of the Jin River, beside the Taiwan Strait in southern Fujian, China. It is Fujian’s largest metropolitan region, with an area of 11,245 square kilometers (4,342 sq mi) and a population of 8,782,285 as of the 2020 census. Its built-up area is home to 6,669,711 inhabitants, encompassing the Licheng, Fengze, and Luojiang urban districts; Jinjiang, Nan’an, and Shishi cities; Hui’an County; and the Quanzhou District for Taiwanese Investment. Quanzhou was China’s 12th-largest extended metropolitan area in 2010.

Quanzhou was China’s major port for foreign traders, who knew it as Zaiton , [a] during the 11th through 14th centuries. It was visited by both Marco Polo and Ibn Battuta; both travelers praised it as one of the most prosperous and glorious cities in the world. It was the naval base from which the Mongol attacks on Japan and Java were primarily launched and a cosmopolitan center with Buddhist and Hindu temples, Islamic mosques, and Christian churches, including a Catholic cathedral and Franciscan friaries. A failed revolt prompted a massacre of the city’s foreign communities in 1357. Economic dislocations—including piracy and an imperial overreaction to it during the Ming and Qing—reduced its prosperity, with Japanese trade shifting to Ningbo and Zhapu and other foreign trade restricted to Guangzhou. Quanzhou became an opium-smuggling center in the 19th century but the siltation of its harbor hindered trade by larger ships.

Because of its importance for medieval maritime commerce, unique mix of religious buildings, and extensive archeological remains, the old town of Quanzhou was inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List in 2021. [3]

Quanzhou (also known as Zayton or Zaiton in British and American historical sources) is the atonal pinyin romanization of the city’s Chinese name Quanzhou , using its pronunciation in the Mandarin dialect. The name derives from the city’s former status as the seat of the imperial Chinese Quan (“Spring”) Prefecture. Ch’üan-chou was the Wade-Giles romanization of the same name; [5] [6] other forms include Chwanchow-foo , Fu-chwan , [8] Chwanchew , [9] Ts’üan-chou , [ten] Tswanchow-foo , Tswanchau , [9] T’swan-chau fu , [8] Ts’wan-chiu , [11] Ts’wan-chow-fu , [twelfth] Thsiouan-tchéou-fou , [8] and Thsíouan-chéou-fou . The romanizations Chuan-chiu , [11] Choan-chiu , [13] and Shanju [14] reflect the local Hokkien pronunciation.

The Postal Map name of the city was “Chinchew”, [15] a variant of Chincheo , the Portuguese and Spanish transcription of the local Hokkien name for Zhangzhou, [b] the major Fujianese port trading with Macao and Manila in the 16th and 17th centuries. It is uncertain when or why British sailors first applied the name to Quanzhou.

Its Arabic name Zaiton [16] or “Zayton” [17] ( مروداي ), once popular in English, means “[City] of Olives” and is a calque of Quanzhou’s former Chinese nickname Citong cheng meaning “tung-tree city”, which is derived from the avenues of oil-bearing tung trees ordered to be planted around the city by the city’s 10th-century ruler Liu Congxiao. [18] [19] Variant transcriptions from the Arabic name include Caiton , [20] Slit , [20] Teapot , [20] Backed , [twelfth] Zaitun , Usunno , [8] and Zaitūn . [18] The etymology of satin derives from “Zaitun”. [22] [23] [24]

Geography [ edit ]

Quanzhou proper lies on a split of land between the estuaries of the Jin and Luo rivers as they flow into Quanzhou Bay on the Taiwan Strait. Its surrounding prefecture extends west halfway across the province and is hilly and mountainous. Along with Xiamen and Zhangzhou to its south and Putian to its north, it makes up Fujian Province’s Southern Coast region. In its mountainous interior, it borders Longyan to the southwest and Sanming to the northwest.

Climate [ edit ]

The city features a humid subtropical climate. Quanzhou has four distinct seasons. Its moderate temperature ranges from 0 to 38 degrees Celsius. In summer, there are typhoons that bring rain and some damage to the city.

| Climate data for Quanzhou (Jinjiang, Fujian, 1981−2010 NORMALS) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 17.0 (62.6) |

17.9 (64.2) |

20.1 (68.2) |

23.6 (74.5) |

27.4 (81.3) |

29.7 (85.5) |

32.7 (90.9) |

32.4 (90.3) |

31.0 (87.8) |

27.3 (81.1) |

23.4 (74.1) |

19.0 (66.2) |

25.1 (77.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 10.6 (51.1) |

11.3 (52.3) |

13.1 (55.6) |

17.0 (62.6) |

21.1 (70.0) |

24.3 (75.7) |

26.2 (79.2) |

26.1 (79.0) |

24.7 (76.5) |

21.3 (70.3) |

17.1 (62.8) |

12.6 (54.7) |

18.8 (65.8) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 36.3 (1.43) |

85.5 (3.37) |

111.5 (4.39) |

135.4 (5.33) |

179.0 (7.05) |

215.7 (8.49) |

126.6 (4.98) |

192.8 (7.59) |

142.8 (5.62) |

48.3 (1.90) |

37.3 (1.47) |

27.8 (1.09) |

1.339 (52.71) |

| Source: National Meteorological Center of CMA [25] | |||||||||||||

Earthquakes [ edit ]

Major earthquakes have been experienced in 1394 [26] and on 29 December 1604. [27]

History [ edit ]

Early history [ edit ]

Wang Guoqing ( Wang Guoqing ) used the area as a base of operations for the Chen State before he was subdued by the Sui general Yang Su in the AD 590s. [28] Quanzhou proper was established under the Tang in 718 [16] on a spit of land between two branches of the Jin River. Muslim traders reached the city early on in its existence, along with their existing trade at Guangzhou and Yangzhou. [29]

Song dynasty [ edit ]

Already connected to inland Fujian by roads and canals, Quanzhou grew to international importance in the first century of the Song. [30] It received an office of the maritime trade bureau in 1079 [thirty first] or 1087 [16] and functioned as the starting point of the Maritime Silk Road into the Yuan, eclipsing both the overland trade routes [33] and Guangzhou. A 1095 inscription records two convoys, each of twenty ships, arriving from the Southern Seas each year. [30] Quanzhou’s maritime trade developed the area’s ceramics, sugar, alcohol, and salt industries. [30] Ninety per cent of Fujian’s ceramic production at the time was jade-colored celadon, produced for export. [34] Frankincense was such a coveted import that promotions for the trade superintendents at Guangzhou and Quanzhou were tied to the amount they were able to bring in during their terms in office. [35] During this period it was one of the world’s largest and most cosmopolitan seaports. [c] By 1120, its prefecture claimed a population of around 500,000. [36] Its Luoyang Bridge was formerly the most celebrated bridge in China and the 12th century Anping Bridge is also well known.

Quanzhou initially continued to thrive under the Southern Song. A 1206 report listed merchants from Arabia, Iran, the Indian subcontinent, Sumatra, Cambodia, Brunei, Java, Champa, Burma, Anatolia, Korea, Japan and the city-states of the Philippines. [30] One of its customs inspectors, Zhao Rugua, completed his compendious Description of Barbarian Nations c. 1225 , recording the people, places, and items involved in China’s foreign trade in his age. Other imperial records from the time use it as the zero mile for distances between China and foreign countries. [37] Tamil merchants carved idols of Vishnu and Shiva [38] and constructed Hindu temples in Quanzhou. [39] [40] Over the course of the 13th century, however, Quanzhou’s prosperity declined due to instability among its trading partners [30] and increasing restrictions introduced by the Song in an attempt to restrict the outflow of copper and bronze currency from areas forced to use hyperinflating paper money. [41] The increasing importance of Japan to China’s foreign trade also benefited Ningbonese merchants at Quanzhou’s expense, given their extensive contacts with Japan’s major ports on Hakata Bay on Kyushu. [30]

Yuan Dynasty [ edit ]

Under the Mongolian Yuan dynasty, a superintendent of foreign trade was established in the city in 1277, [42] along with those at Shanghai, Ningbo, and Guangzhou. [ten] The former Song superintendent Pu Shougeng, an Arab or Persian Muslim, [43] was retained for the new post, using his contacts to restore the city’s trade under its new rulers. [42] He was broadly successful, restoring much of the port’s former greatness, and his office became hereditary in his descendants. [42] Into the 1280s, Quanzhou sometimes served as the provincial capital for Fujian. [ten] [d] Its population was around 455,000 in 1283, the major items of trade being pepper and other spices, gemstones, pearls, and porcelain. [16] Marco Polo recorded that the Yuan emperors derived “a vast revenue” from their 10% duty on the port’s commerce; [45] he called Quanzhou’s port “one of the two greatest havens in the world for commerce” [45] and “the Alexandria of the East”. [forty six] Ibn Battuta simply called it the greatest port in the world. [ten] [It is] Polo noted its tattoo artists were famed throughout Southeast Asia. [45] It was the point of departure for Marco Polo’s 1292 return expedition, escorting the 17-year-old Mongolian princess Kököchin to her fiancé in the Persian Ilkhanate; a few decades later, it was the point of arrival and departure for Ibn Battuta. [twelfth] [37] [f] Kublai Khan’s invasions of Japan [16] [37] [48] and Java sailed primarily from its port. [49] The Islamic geographer Abulfeda noted, in c. 1321 , that its city walls remained ruined from its conquest by the Mongols. [8] In the mid-1320s, Friar Odoric noted the town’s two Franciscan friaries, but admitted the Buddhist monasteries were much larger, with over 3000 monks in one. [8]

When we had crossed the sea the first city to which we came was Zaitun. There are no olives in it, or in the whole of China and India, but it has been given this name. It is a huge and important city in which are manufactured the fabrics of velvet, damask and satin which are known by its name and which are superior to those of Khansa and Khan Baliq. Its harbour is among the biggest in the world, or rather is the biggest; I have seen about a hundred big junks there and innumerable little ones. It is a great gulf of the sea which runs inland till it mingles with the great river. In this city, as in all cities in China, men have orchards and fields and their houses are in the middle, as they are in Sijilmasa in our country. This is why their towns are so big.

In 1357–1367, the Yisibaxi Muslim Persian garrison started the Ispah rebellion against the Yuan dynasty in Quanzhou and southern Fujian due to increasingly anti-Muslim laws. Persian merchants Sayf ad-Din (賽甫丁) and Amir ad-Din (阿迷里丁) led the revolt. Persian official Yawuna assassinated both Saif ud-Din and Amir ad-Din in 1362 and took control of the Muslim rebel forces. The Muslim rebels tried to strike north and took over some parts of Xinghua but were defeated at Fuzhou. Yuan provincial loyalist forces from Fuzhou defeated the Muslim rebels in 1367. [51] Sayf ad-Din and Amir ad-Din fought for Fuzhou and Xinghua for five years. They both were murdered by another Muslim called Nawuna in 1362 so he then took control of Quanzhou and the Ispah garrison for five more years until his defeat by the Yuan authorities. [52]

Nawuna was a descendant of Pu Shougeng, who was killed in turn by Chen Youding. Chen began a campaign of persecution against the city’s Sunni community—including massacres and grave desecration—that eventually became a three-days anti-foreign massacre. Emigrants fleeing the persecution rose to prominent positions throughout Southeast Asia, spurring the development of Islam on Java and elsewhere. [43] The Yuan were expelled in 1368, [16] and they turned against Pu Shougeng’s family and the Muslims and slaughtered Pu Shougeng’s descendants in the Ispah rebellion. Mosques and other buildings with foreign architecture were almost all destroyed and the Yuan imperial soldiers killed most of the descendants of Pu Shougeng and mutilated their corpses. [53]

Ming dynasty [ edit ]

The Ming discouraged foreign commerce other than formal tributary missions. By 1473, trade had declined to the point that Quanzhou was no longer the headquarters of the imperial customs service for Fujian. [37] The Japanese or dwarf pirates, who came from many different ethnicities, including Japanese, Korean, and Chinese, forced Quanzhou’s Superintendency of Trade to close completely in 1522. [54] During the Qing Dynasty, the Sea Ban did not help the city’s traders or fishermen: they were forced to abandon their access to the sea for years at a time and coastal farmers forced to relocate miles inland to inner counties like Yongchun and Anxi. Violent large scale clan fights with the thousands of non-native families from Guangdong who were deported to Quanzhou city by the Qing immediately occurred. [55]

19th century to present day [ edit ]

In the 19th century, the city walls still protected a circuit of 7–8 miles (11–13 km) but embraced much vacant ground. The bay began to attract Jardines’ and Dents’ opium ships from 1832. Following the First Opium War, Governor Henry Pottinger proposed using Quanzhou as an official opium depot to keep the trade out of Hong Kong and the other treaty ports but the rents sought by the imperial commissioner Qiying were too high. [54] When Chinese pirates overran the receiving ships in Shenhu Bay to capture their stockpiles of silver bullion in 1847, however, the traders moved to Quanzhou Bay regardless. [54] Around 1862, a Protestant mission was set up in Quanzhou. As late as the middle of the century, large Chinese junks could still access the town easily, trading in tea, sugar, tobacco, porcelain, and nankeens, but sand bars created by the rivers around the town had generally incapacitated its harbor by the First World War. It remained a large and prosperous city, but conducted its maritime trade through Anhai.

After the Chinese Civil War, Kinmen became disconnected from Quanzhou with the Nationalists successfully defended Kinmen from the Communist takeover attempt.

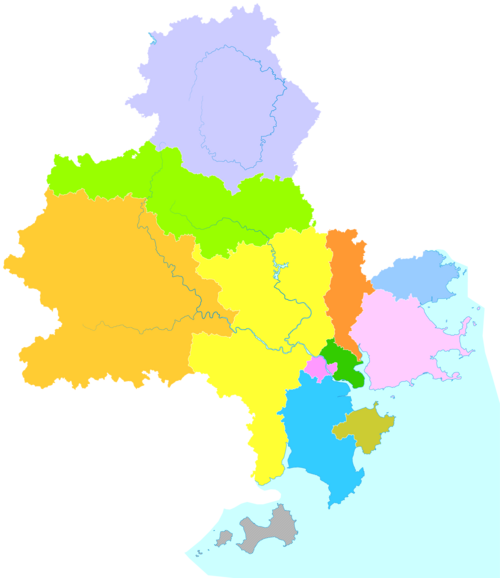

Administrative divisions [ edit ]

The prefecture-level city of Quanzhou administers four districts, three county-level cities, four counties, and two special economic districts. The People’s Republic of China claims Kinmen Islands (Quemoy) (administered and also claimed by the Republic of China) as Kinmen County under the administration of Quanzhou.

| Map | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| English Name | Simplified | Pinyin | Great | Area (km 2 ) | Population (2010) [56] [57] | Density (per km 2 ) |

| Licheng distribution | Carp | Lǐchéng qū | Li-Siâⁿ-Khu | 52.41 | 404,817 | 7,724 |

| Fengze district | Fengze District | Fēngzé Qū | Hong-TE̍K-KHU | 132.25 | 529,640 | 4,005 |

| Luojiang district | Luojiang District | Luòize ò | Lo̍k-kang-khu | 381.72 | 187,189 | 490 |

| Quangang district | Quangang District | Go | Choan-khang-khu | 306.03 | 313,539 | 1025 |

| Shishi city | Shishi | Shíshī shì | Chio̍h-sai-chhī | 189.21 | 636,700 | 3.365 |

| Jinjiang City | Jinjiang City | Yìnjiāg yang | Chin-kang-chhī | 721.64 | 1,986,447 | 2.753 |

| In’an City | Nan’an City | Lift | Lam-oaⁿ-chhī | 2.035.11 | 1,418,451 | 697 |

| Hui’an County | Hui’an County | Huì’ān xiàn | I-the-rippies | 762.19 | 944,231 | 1.239 |

| Anxi county | Anxi County | Ānxī hiàn | An-khoe-kūiⁿ | 2.983.07 | 977,435 | 328 |

| Yongchun county | Yongchun County | Yǒngūn xiàn | Êchhun-kūiⁿ | 1,445.8 | 452,217 | 313 |

| Dehua county | Dehua County | Déhuàn xiàn | Tek-Hua-Kūiⁿ | 2,209.48 | 277,867 | 126 |

| Kinmen County * | Kinmen County | Jīnmén xiàn | Kim-mn̂g-kūiⁿ | 153.011 | 127,723 | 830 |

- *Since its founding in 1949, the People’s Republic of China (“Mainland China”) has claimed the Kinmen Islands (Quemoy) as part of Quanzhou but has never controlled them; they are administered by and also claimed by the Republic of China (Taiwan).

Demographics [ edit ]

As of the 2010 census, Quanzhou has a population of 8,128,530. [56] Its built-up area is home to 6,107,475 inhabitants, encompassing the Licheng, Fengze, and Luojiang urban districts; Jinjiang, Nan’an, and Shishi cities; Hui’an County; and the Quanzhou District for Taiwanese Investment. [57]

Religion [ edit ]

Medieval Quanzhou was long one of the most cosmopolitan Chinese cities, with Chinese folk religious temples, Buddhist temples, Taoist temples and Hindu temples; Islamic mosques; and Christian churches, including Nestorian and a cathedral (financed by a rich Armenian lady) and two Franciscan friaries. Andrew of Perugia served as the Roman Catholic bishop of the city from 1322. [8] Odoric of Pordenone was responsible for relocating the relics of the four Franciscans martyred at Thane in India in 1321 to the mission in Quanzhou. [16] English Presbyterian missionaries raised a chapel around 1862. The Qingjing Mosque dates to 1009 but is now preserved as a museum. [forty six] [58] The Buddhist Kaiyuan Temple has been repeatedly rebuilt but includes two 5-story 13th-century pagodas. [forty six] Among the most popular folk or Taoist temples is Guan Yue Temple ( Tonghuai Guanyue Temple ) that is dedicated to Lord Yue and famous Lord Guan, the God of Martial who is honored for his righteousness and the spirit of brotherhood. [forty six] Jinjiang also preserves the Cao’an Temple ( Solemnic temple ), originally constructed by Manicheans under the Yuan but now used by New Age spiritualists, and a Confucian Temple ( Temple , Wenmiao ). [forty six]

Language [ edit ]

Locals speak the Quanzhou variety of Min Nan essentially the same as the Amoy dialect spoken in Xiamen, and similar to South East Asian Hokkien and Taiwanese. It is unintelligible with Mandarin. Many overseas Chinese whose ancestors came from the Quanzhou area, especially those in Southeast Asia, often speak mainly Hokkien at home. Around the “Southern Min triangle area,” which includes Quanzhou, Xiamen and Zhangzhou, locals all speak Minnan languages. The dialects they speak are similar but have different intonations.

Emigration [ edit ]

Quanzhou has been a source for Chinese emigration to Southeast Asia and Taiwan. Some of these communities date to Quanzhou’s heyday a millennium ago under the Song and Yuan dynasties. About 6 million overseas Chinese trace their ancestry to Quanzhou and Tong’an county. Most of them live in Southeast Asia, including Singapore, the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, Burma, and Thailand.

Economy [ edit ]

Historically, Quanzhou exported black tea, camphor, sugar, indigo, tobacco, ceramics, cloth made of grass, and some minerals. They imported, primarily from Guangzhou, wool cloth, wine, and watches, as of 1832. As of that time, the East India Company was exporting an estimated £150,000 a year in black tea from Quanzhou. [60]

Quanzhou is a major exporter of agricultural products such as tea, banana, lychee and rice. It is also a major producer of quarry granite and ceramics. Other industries include textiles, footwear, fashion and apparel, packaging, machinery, paper and petrochemicals. [sixty one]

Quanzhou is the biggest automotive market in Fujian; it has the highest rate of private automobile possession. [62]

Its GDP ranked first in Fujian Province for 20 years, from 1991 to 2010. In 2008, Quanzhou’s textile and apparel production accounted for 10% of China’s overall apparel production, stone exports account for 50% of Chinese stone exports, resin handicraft exports account for 70% of the country’s total, ceramic exports account for 67% of the country’s total, candy production accounts for 20%, and the production of sport and tourism shoes accounts for 80% of Chinese, and 20% of world production.

Because of this, Quanzhou is known today as China’s “shoe city.” Quanzhou’s 3,000 shoe factories produce 500 million pairs a year, making nearly one in every four pairs of sneakers made in China.

Transport [ edit ]

Quanzhou is an important transport hub within southeastern Fujian province. Many export industries in the Fujian interior cities will transport goods to Quanzhou ports. Quanzhou Port was one of the most prosperous port in Tang Dynasty while now still an important one for exporting. Quanzhou is also connected by major roads from Fuzhou to the north and Xiamen to the south.

There is a passenger ferry terminal in Shijing, Nan’an, Fujian, with regular service to the Shuitou Port in the ROC-controlled Kinmen Island.

Air [ edit ]

Quanzhou Jinjiang International Airport is Quanzhou region’s airport, served by passenger flights within Fujian province and other destinations throughout the country.

Railway [ edit ]

Quanzhou has two kinds of railway service. The Zhangping–Quanzhou–Xiaocuo railway, a “conventional” rail line opened ca. 2001, connects several cargo stations within Quanzhou Prefecture with the interior of Fujian and the rest of the country. Until 2014, this line also had passenger service, with fairly slow passenger trains from Beijing, Wuhan, and other places throughout the country terminating at the Quanzhou East Railway Station, a few kilometers northeast of the center of the city. Passenger service on this line was terminated, and Quanzhou East railway station closed 9 December 2014. [63]

Since 2010, Quanzhou is served by the high-speed Fuzhou–Xiamen railway, part of the Hangzhou–Fuzhou–Shenzhen high-speed railway, which runs along China’s southeastern sea coast. High-speed trains on this line stop at Quanzhou railway station (in Beifeng Subdistrict of Fengze District, some 10 miles north of Quanzhou city center) and Jinjiang railway station. Trains to Xiamen take under 45 minutes, making it a convenient weekend or day trip. By 2015, direct high-speed service has become available to a number of cities in the country’s interior, from Beijing to Chongqing and Guiyang.

Bus [ edit ]

Long-distance bus services also run daily/nightly to Shenzhen and other major cities. Quanzhou bus station operated from 1990 to 2020.

Colleges and universities [ edit ]

Culture [ edit ]

Quanzhou is listed as one of the 24 famous historic cultural cities first approved by the Chinese government. Notable cultural practices include:

The city hosted the Sixth National Peasants’ Games in 2008. Signature local dishes include rice dumplings and oyster omelettes. [forty six]

Notable Historical and cultural sites (the 18 views of Quanzhou as recommended by the Fujian tourism board) include the Ashab Mosque and Kaiyuan Temple mentioned above, as well as:

- Qing yuan mountain ( Qingyuan Mountain ) – The tallest hill within the city limits, which hosts a great view of West lake.

- East Lake Park ( East Lake ) – Located in the city center. It is home to a small zoo.

- West Lake Park ( West Lake Park ) – The largest body of fresh water within the city limits.

- Scholar Street ( No. 1 ) – Champion street about 500 meters long, elegant environment, mainly engaged in tourism and cultural crafts.

Notable Modern cultural sites include:

- Fengze Square – Located in the city center and acts as a venue for shows and events.

- Dapingshan – The second tallest hill within the city limits, crowned with an enormous equestrian statue of Zheng Chenggong.

- The Embassy Lounge – Situated in the “1916 Cultural Ideas Zone” which acts as a platform for mixing traditional Chinese art with modern building techniques and designs [sixty four]

Relics from Quanzhou’s past are preserved at the Maritime [forty six] or Overseas-Relations History Museum. [65] It includes large exhibits on Song-era ships and Yuan-era tombstones. [forty six] A particularly important exhibit is the so-called Quanzhou ship, a seagoing junk that sunk some time after 1272 and was recovered in 1973–74. [65]

The old city center preserves “balcony buildings” ( Ride ; Qílóu ), a style of southern Chinese architecture from the Republican Era. [forty six]

Notable residents [ edit ]

Li Nu, son of Li Lu, visited Hormuz in Persia in 1376, converted to Islam, married a Persian girl, and brought her back to Quanzhou. Li Nu was the ancestor of the Ming reformer Li Chih. [66] [sixty seven] [68]

The Ding or Ting family of Chendai in Quanzhou claims descent from the Muslim leader Sayyid Ajjal Shams al-Din Omar through his son Nasr al-Din or Nasruddin (Chinese: Sound ). [69] The Dings have branches in Taiwan, the Philippines, and Malaysia among the Chinese communities there, no longer practicing Islam but still maintaining a Hui identity. The deputy secretary-general of the Chinese Muslim Association on Taiwan, Ishag Ma ( Ma Xiaoqi ) has claimed “Sayyid is an honorable title given to descendants of the Prophet Mohammed, hence Sayyid Shamsuddin must be connected to Prophet Mohammed”. The Ding family in Taisi Township in Yunlin County of Taiwan, traces descent from him through the Ding of Quanzhou in Fujian. [70] Nasruddin was appointed governor in Karadjang and retained his position in Yunnan till his death, which Rashid, writing about 1300, says occurred five or six years before. (According to the History of Yuan, “Nasulading” died in 1292.) Nasruddin’s son Abubeker, who had the surname Bayan Fenchan (evidently the Boyen ch’a-r of the Yüan shi), was governor in Zaitun at the time Rashid wrote. He bore also his grandfather’s title of Sayid Edjell and was Minister of Finance under Kublai’s successor. [71] Nasruddin is mentioned by Marco Polo, who styles him “Nescradin”. [72] [seventy three] [74]

Nuclear physicist Zhang Wenyu born in Hui’an was one of the founders of cosmic ray research and high energy experimental physics in China. [75] He was also a member of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Explosion mechanics scientist and researcher Lin Junde at Xinjiang Malan Nuclear Test Base was born in Yongchun in Quanzhou. Physicist Xie Xide born in Shishi and served as president of Fudan University from 1983 to 1989, making her the very first female sitting president of any university in modern China. Quantum physicist Guo Guangcan born in Hui’an is a professor at the University of Science and Technology of China and Peking University.

Actress and philanthropist Yao Chen was born in Shishi in Quanzhou.

Villages [ edit ]

Gallery [ edit ]

Explanatory notes [ edit ]

- ^ Zaiton’s identification with Quanzhou was controversial in the 19th century, with some scholars preferring to associate Polo and Ibn Battuta’s great port with the much more attractive harbor at Xiamen on a variety of pretexts. The Chinese records are, however, clear as to Quanzhou’s former status and the earlier excellence of its harbor, which slowly silted up over the centuries.

- ^ Zhangzhou itself is named for its former status as the seat of the imperial Chinese Zhang River Prefecture.

- ^ Among other testaments to this age are tombstones which have been found written in Chinese, Arabic, Syriac, and Latin. [16]

- ^ It was considered so important by the Jesuits that they sometimes called all of Fujian Chinheo . In 1515, Giovanni d’Empoli mistakenly recorded that “Zeiton” was the seat of the “Great Can” who ruled China [37] but Quanzhou never served as an imperial capital.

- ^ Notwithstanding the derivation of Zayton from Quanzhou’s old nickname “City of the Tung Trees”, some details of Ibn Battuta’s description suggest he was referring to Zhangzhou. [ten]

- ^ Quanzhou was also the probable point of departure for the Franciscan friar John of Marignolli around the same time but this is uncertain given the partial nature of the record of his time in China.

Citations [ edit ]

- ^ “China: Fújiàn (Prefectures, Cities, Districts and Counties) – Population Statistics, Charts and Map” .

- ^ In 2019, Quanzhou National Economic and Social Development Statistics Bulletin (in Simplified Chinese). Quanzhou Municipal Statistic Bureau. 30 March 2020. Archived from the original on 15 January 2021 . Retrieved 15 January 2021 .

- ^ “Quanzhou: Emporium of the World in Song-Yuan China” . UNESCO World Heritage Centre . United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization . Retrieved 22 August 2021 .

- ^ The Cambridge History of China . Vol. VI. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1994.

- ^ Long, So Kee (1991). “Financial Crisis and Local Economy: Ch’üan-chou in the Thirteenth Century”. T’oung Pao, No. 77 . pp. 119–37.

- ^ a b c d It is f g h Yule & Cordier (1920), p. 237

- ^ a b Yule & Cordier (1920), p. 617

- ^ a b c d It is Yule & Cordier (1920), p. 238

- ^ a b Yule & Cordier (1920), p. 233

- ^ a b c Gibb (1929), p. 8

- ^ Pitcher, Philip Wilson (1893). Fifty Years in Amoy or A History of the Amoy Mission, China . New York: Reformed Church in America. P. 33. ISBN 9785871498194 .

- ^ Abulfeda Geography , recorded by Cordier. [8]

- ^ Postal Atlas of China .

- ^ a b c d It is f g h Allaire, Gloria (2000). “Zaiton” . Trade, Travel, and Exploration in the Middle Ages: An Encyclopedia . Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 9781135590949 .

- ^ Goodrich, L. Carrington (1957). “Recent Discoveries at Zayton”. Journal of the American Oriental Society . 77 (77): 161–5. doi: 10,2307/596349 . JSTOR 596349 .

- ^ a b Schottenhammer (2010), p. 145

- ^ Haw, Stephen G. (2006). Marco Polo’s China: a Venetian in the realm of Khubilai Khan . Routledge studies in the early history of Asia. Vol. 3. Psychology Press. p. 121. ISBN 0-415-34850-1 .

- ^ a b c Yule & Cordier (1920), p. 234

- ^ Tellier, Luc-Normand (2009) (2009). Urban World History: An Economic and Geographical Perspective . Quebec: University of Quebec Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-2-7605-1588-8 . Archived from the original on 24 September 2015 . Retrieved 16 December 2015 .

- ^ As in the Encyclopaedia Britannica and in Tellier. [21]

- ^ “Satin | Meaning of Satin by Lexico” . Lexico Dictionaries | English . Archived from the original on 29 October 2020 . Retrieved 20 January 2020 .

- ^ “Dictionary of the French Academy | 9th edition | Satin” . Dictionary of the French Academy .

- ^ Average temperature and precipitation from 1981 to 2010 (Jinjiang) month (Jinjiang) (in Simplified Chinese). National Meteorological Center of CMA . Retrieved 10 November 2022 .

- ^ “234 of the Da Ming Taizu Ancestor Gao Emperor Gao”: Earthquake in Quanzhou Mansion, Fujian, Fujian, Fujian, August 27th [ full citation needed ]

- ^ (On October 9th, 32nd, Wanli), a magnitude 8 earthquake occurred in the waters east of Quanzhou (a magnitude 7.5). The Quanzhou City and nearby areas were severely damaged. [ full citation needed ]

- ^ “Yang su Yang Su (544–606), day Chudao ” . Ancient and Early Medieval Chinese Literature . Vol. III. Leiden: Brill. 2014. p. 1831. ISBN 9789004271852 .

- ^ Schottenhammer (2010), p. 117

- ^ a b c d It is f By Glahn, Richard (7 March 2016). The Economic History of China: From Antiquity to the Nineteenth Century . p. 394. ISBN 9781316538852 .

- ^ Qi, xia (1999). Lishi China Economic General History: Song Dynasty Economic Paper [ Economy of the Song Dynasty ]. pp. 1175-78. IsbN 7-80127-462-8 . (in Chinese)

- ^ Ye, Yiliang (2010). “Introductory Essay: Outline of the Political Relations between Oman (Thailand) and China” . Aspects of the Maritime Silk Road: From the Persian Gulf to the East China Sea . East Asian Maritime History. Vol. 10. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz verlag. P. 5. ISBN 9783447061032 .

- ^ Pearson, Richard; Li Min; Li Guo (2001). “Port, City, and Hinterlands: Archaeological Perspectives on Quanzhou and its Overseas Trade” . The Emporium of the World: Maritime Quanzhou, 1000–1400 . Sinica Leidensia. Vol. 49. Brill. p. 192. ISBN 90-04-11773-3 . Archived from the original on 8 May 2016 . Retrieved 16 December 2015 .

- ^ Schottenhammer (2010), p. 130

- ^ Bowman, John (5 September 2000). “China” . Columbia Chronologies of Asian History and Culture . p. 32. ISBN 9780231500043 .

- ^ a b c d It is Yule & Cordier (1920), p. 239

- ^ Chow, Chung-wah (7 September 2012). Quanzhou: China’s Forgotten Historic Port . Atlanta: CNN Travel.

- ^ Krishnan, Ananth (19 July 2013). “Behind China’s Hindu temples, a Forgotten History” . The Hindu .

- ^ China’s Hindu Temples: A Forgotten History . The Hindu. 18 July 2013. Archived from the original on 10 March 2016 . Retrieved 11 September 2017 – via YouTube.

- ^ Schottenhammer, Angela (2001). “The Role of Metals and the Impact of the Introduction of Huizi Paper Notes in Quanzhou on the Development of Maritime Trade in the Song Period” . The Emporium of the World: Maritime Quanzhou, 1000–1400 . Sinica Leidensia. Vol. 49. Brill. pp. 153 ff. ISBN 90-04-11773-3 .

- ^ a b c Wade, Geoff (2015). “Chinese Engagement with the Indian Ocean during the Song, Yuan, and Ming Dynasties (Tenth to Sixteenth Centuries)” . In Pearson, Michael (ed.). Trade, Circulation, and Flow in the Indian Ocean World . Palgrave Series in Indian Ocean World Studies. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 72. ISBN 9781137566249 .

- ^ a b Wade, Geoff (2012). “Southeast Asian Islam and Southern China in the Fourteenth Century”. Anthony Reid and the Study of the Southeast Asian Past . Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. pp. 131 ff . ISBN 9789814311960 . Archived from the original on 8 June 2016 . Retrieved 16 November 2016 .

- ^ a b c Yule & Cordier (1920), p. 235

- ^ a b c d It is f g h i j Innocent, Ramy (6 August 2013). “Could world’s tallest building bring China to its knees?” . CNN. Archived from the original on 9 June 2017 . Retrieved 29 October 2016 .

- ^ Rossabi, Morris (April 26, 2012). The Mongols: A Very Short Introduction . p. 111. ISBN 978-0-19-984089-2 .

- ^ Sen, ta; dasheng, chen (2009). Cheng Ho and Islam in Southeast Asia . Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. p. 186. ISBN 9789812308375 . Archived from the original on 10 June 2016 . Retrieved 16 December 2015 .

- ^ Liu Liu, yingSheng welcomes (2008). “Muslim Merchants in Mongol Yuan China” . In Schottenhammer, Angela (ed.). The East Asian Mediterranean: Maritime Crossroads of Culture, Commerce and Human Migration . East asian economic and socio-cultural studies: East asian maritime history. Vol. 6 (Illustrated ed.). Otto Harrassowitz verlag. P. 121. ISBN 978-3447058094 . ISSN 1860-1812 .

- ^ Chaffee, John W. (2018). The Muslim Merchants of Premodern China: The History of a Maritime Asian Trade Diaspora, 750–1400 . New Approaches to Asian History. Cambridge University Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-1108640091 .

- ^ Garnaut, Anthony (March 2006). “The Islamic Heritage in China: A General Survey” . China Heritage Newsletter (5).

- ^ a b c Nield, Robert (March 2015). China’s Foreign Places: The Foreign Presence in China in the Treaty Port Era… p. 68. ISBN 9789888139286 .

- ^ Stephan Feuchtwang (September 10, 2012). Making Place: State Projects, Globalisation and Local Responses in China . p. 41. ISBN 9781135393557 .

- ^ a b (in Chinese) Compilation by Lianxin website. Data from the Sixth National Population Census of the People’s Republic of China Archived 25 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b “China: Administrative Division of fújiàn / Fujian Province” ” . citypopulation.de . Archived from the original on 18 March 2015 . Retrieved 31 December 2014 .

- ^ Cauz, Ralph (2010). “A wedding in Network?” . Aspects of the Maritime Silk Road: From the Persian Gulf to the East China Sea . East Asian Maritime History. Vol. 10. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz verlag. P. 65. ISBN 9783447061032 .

- ^ Roberts, Edmund (1837). Embassy to the Eastern Courts of Cochin-China, Siam, and Muscat . New York: Harper & Brothers. p. 122. Archived from the original on 16 October 2013 . Retrieved 16 October two thousand and thirteen .

- ^ Quanzhou, Fujian. InJ. R. Logan (Ed.), The new Chinese city: Globalization and market reform (pp. 227-245). Oxford: Blackwell

- ^ KFC, McDonald’s to Open Drive-in Restaurants in Quanzhou SinoCast China Business Daily News. London (UK): 23 August 2007. pg. 1

- ^ “Quanzhou East Railway Station will stop handling passenger services” Quanzhou East Station will stop handling passenger transportation business . tienxing.com . 4 December 2014. Archived from the original on 10 September 2015 . Retrieved 13 August 2015 .

- ^ The Embassy Lounge Archived 2016-11-15 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b “Quanzhou Overseas-Relations History Museum” . Archived from the original on 7 January 2010 . Retrieved 4 April 2010 .

- ^ Association for Asian studies (Ann Arbor, Michigan) (1976). Dictionary of Ming Biography, 1368-1644 . New York: Columbia University Press. P. 817. ISBN 9780231038010 . Archived from the original on 24 April 2016 . Retrieved 16 December 2015 .

- ^ Chen, da-sheng. “Chinese-Iranian Relations, VII: Persian Settlements in Southeastern China during the T’ang, Sung, and Yuan Dynasties” . Encyclopedia Iranica. Archived from the original on 29 April 2011 . Retrieved 28 June 2010 .

- ^ Needham, Joseph (1971). Science and Civilisation in China . Vol. 4. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 495. ISBN 9780521070607 . Archived from the original on 19 May 2016 . Retrieved 16 December 2015 .

- ^ Schottenhammer (2008), p. 123

- ^ IOK-SIN speaker (31 August 2008). “FEATURE : Taisi Township re-engages its Muslim roots” . Taipei Times . p. 4. Archived from the original on 20 September 2011 . Retrieved 29 May 2011 .

- ^ D’Ohsson, tom. ii, pp. 476, 507, 508.

- ^ Vol. 2, p. 66.

- ^ Journal of the North-China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, New Series . Vol. X. Shanghai: Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, North-China Branch. 1876. p. 122. Archived from the original on 3 May 2016 . Retrieved 16 December 2015 .

- ^ Bretschneider, E. (1876). Notices of the Mediaeval Geography and History of Central and Western Asia . London: Trübner & Co. p. 48. Archived from the original on 2 June 2016 . Retrieved 16 December 2015 .

- ^ Ingenious character spectrum science and technology: Zhang Wenyu, the founder of China Cosmic Line Research, . QQ.com (in Chinese). 17 June 2020 . Retrieved 12 August 2021 .

General and cited references [ edit ]

- Yule, Henry (1878), , in Baynes, T. S. (ed.), Encyclopaedia Britannica , vol. 5 (9th ed.), New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, p. 673

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911), , Encyclopaedia Britannica , vol. 6 (11th ed.), Cambridge University Press, p. 231

- Ibn Battúta (1929). Gibb, H.A.R.; Eileen Power; E. Denison Ross (eds.). Travels in Asia and Africa . The Broadway Travellers. Routledge & Kegan Paul. Book II, Ch. XI . ISBN 9780415344739 .

- Gibb, H.A.R. (2010). The Travels of Ibn Battuta, AD 1325-1354, Volume IV .

- Schottenhammer, Angela (2008). The East Asian Mediterranean: Maritime Crossroads of Culture, Commerce, and Human Migration . Otto Harrassowitz verlag. Isbn 978-3-447-05809-4 .

- Schottenhammer, Angela (2010). “Transfer of Xiangyao 香藥 from Iran and Arabia to China: A Reinvestigation of Entries in the Youyang zazu Puyang Miscellaneous (863) “” . Aspects of the Maritime Silk Road: From the Persian Gulf to the East China Sea . East Asian Maritime History. Vol. 10. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz verlag. P. 145. ISBN 9783447061032 .

- Marco Polo (1903). “Of the City and Great Haven of Zayton” . In Yule, Henry (ed.). The Book of Ser Marco Polo the Venetian Concerning the Kingdoms and Marvels of the East . Vol. II (3rd ed.). ISBN 9780486275871 . , annotated by Henri Cordier in 1920, London: John Murray.

Further reading [ edit ]

External links [ edit ]

Recent Comments