SUPPORT 11 – Wikipedia

| Apollo 11 | |

|---|---|

| Mission emblem | |

|

|

| Mission data | |

| Operator | NASA |

| NSSDC ID | 1969-059a |

| SCN | 04039 |

| Vehicle name | Service and command module of Apollo 11 and Lunar Module of the Apollo 11 |

| Command module | CM-107 |

| Service form | SM-107 |

| Lunar module | LM-5 |

| Vector | Saturn in SA-506 |

| Coled code | Command module: Columbia Lunar module: Eagle |

| Launch | July 16, 1969 13:32:00 UTC |

| Launching place | RAMPA 39A |

| Wing | July 20, 1969 20:17:40 UTC Sea of tranquility 0° 40′ 26,69″ N, 23 ° 28 ′ 22.69 ″ and (based on the IAU Mean Earth Polar Axis coordinate system) |

| Monthly eva duration | 2 h 31 min 40 s |

| Time on lunar surface | 21 h 36 min 20 s |

| I will adjace | July 24, 1969 16:50:35 UTC |

| Fooling site | Pacific Ocean |

| Recovery ship | USS Hornet |

| Duration | 8 days, 3 hours, 18 minutes and 35 seconds |

| Weighs lunar champions | 21.55 kilograms (47.5 lb) |

| Orbital parameters | |

| Orbit | Orbit Selencentrica |

| Lunar orbite number | 30 |

| Time in lunar orbit | 59 h 30 min 25,79 s |

| Monthly apoapsids | 122,4 km |

| Monthly periapsides | 100,9 km |

| Period | 2 h |

| Inclination | 1.25 ° |

| Crew | |

| Number | 3 |

| Members | Neil Armstrong Michael Collins Buzz Aldrin |

From left to right: Armstrong, Collins and Aldrin. |

|

| Apollo program | |

Apollo 11 It was the spatial mission that brought the first men to the moon, the US astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin, on July 20, 1969 at 20:17:40 UTC. Armstrong was the first to set foot on the lunar soil, six hours after the wing, on July 21 at 02:56 UTC; Aldrin joined him 19 minutes later. The two passed about two and a half hours outside the spacecraft, and collected 21.5 kg of lunar material they brought to the ground. The third member of the mission, Michael Collins (pilot of the command module), remained in lunar orbit while the other two were on the surface; 21.5 hours after the wing, the three gathered and Collins pilled the command module Columbia in the trajectory of return to Earth. The mission ended on July 24, with the sickge in the Pacific Ocean.

Launched by a Saturn V rocket by the Kennedy Space Center, on July 16 at 13:32 UTC, Apollo 11 was the fifth mission with a crew of the Apollo della Nasa program. The Apollo spacecraft was made up of three parts: a command module (cm) that housed the three astronauts and is the only part returned to the ground, a service form (SM), which provided the propulsion command module, energy electric, oxygen and water, and a lunar module (LM). The spacecraft entered the lunar orbit after about three days of travel and, once reached, the astronauts Armstrong and Aldrin moved to the lunar module Eagle with which they descended into the sea of tranquility. After setting foot on the moon and having made the first lunar walk of the story, the astronauts used the rise of ascent of Eagle To leave the surface and rejoin Collins on the command module. They therefore released Eagle Before carrying out the maneuvers that would bring them out of the lunar orbit towards a trajectory in the direction of the earth where they drove in the Pacific Ocean on July 24 after more than eight days in space.

The first lunar walk was broadcast live on television for a world audience. In putting the first foot on the surface of the Luna Armstrong commented the event as “a small step for [a] man, a great leap for humanity”. [first] Apollo 11 concluded the race to the space undertaken by the United States and the Soviet Union in the wider scenario of the Cold War, creating the national objective that the President of the United States John F. Kennedy had defined on May 25, 1961 on the occasion of a speech In front of the United States Congress: “Before this decade ends, to land a man on the moon and make him return healthy and except on earth”. [2]

Between the late 1950s and the beginning of the sixties of the twentieth century, the United States of America were engaged in the so -called “Cold War”, a geopolitical rivalry with the Soviet Union. [3] On October 4, 1957, the latter launched Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite. This surprising success unleashed fears and imaginations all over the world. Not only did he serve to demonstrate that the Soviet Union possessed the ability to affect nuclear weapons on intercontinental distances, but also to be able to challenge US expectations regarding military, economic and technological superiority. [4] This made the sputnik crisis arise and triggered the one that will be known as “space race”. [5] President Dwight D. Eisenhower reacted to this news by creating the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) and giving impulse at the beginning of the Mercury program, [6] who had the objective of bringing a man into geocentric orbit. [7] However, on April 12, 1961 the US were anticipated again when the Soviet cosmonaut Jurij Gagarin became the first person in space and the first to orbit the earth. [8] It was another blow to the US pride. [9] Almost a month later, on May 5, 1961, Alan Shepard became the first American in space, completing a 15 -minute suborbital flight. After being recovered in the Atlantic Ocean, he received a call of congratulations from Eisenhower’s successor, John F. Kennedy. [ten]

Kennedy worried about what the citizens of other nations thought of the United States and believed that it was in the national interest not only to be superior to the others, but that it was important as being powerful as it appears as such. It was therefore considered intolerable that the Soviet Union was more advanced in the field of space exploration and that it was determined to beat the United States in a challenge that maximized its chances of victory. [3] Since the Soviet Union could boast the carriers with the highest load capacity, the United States presented a challenge that went beyond the capacity in the production of ballistic systems of the existing generation to equal the Soviets, but which was to present a goal More spectacular, even if not justified by strictly military reasons. After consulting himself with his experts and consultants, Kennedy chose such a project. [11] On May 25, 1961, he turned to the United States congress on “urgent national needs” and declared: [twelfth]

| ( IN )

«I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the Earth. No single space project in this period will be more impressive to mankind, or more important for the long-range exploration of space; and none will be so difficult or expensive to accomplish. We propose to accelerate the development of the appropriate lunar space craft. We propose to develop alternate liquid and solid fuel boosters, much larger than any now being developed, until certain which is superior. We propose additional funds for other engine development and for unmanned explorations-explorations which are particularly important for one purpose which this nation will never overlook: the survival of the man who first makes this daring flight. But in a very real sense, it will not be one man going to the Moon—if we make this judgment affirmatively, it will be an entire nation. For all of us must work to put him there.» |

( IT ) «I believe that this nation should be committed to achieving the goal, before it ends this decade, to land a man on the moon and to make him return healthy and safe to earth. No spatial project of this period will be more impressive for mankind, or more important for long -haul spatial exploration; And nobody will be so difficult and expensive to do. We propose to accelerate the development of the appropriate lunar vehicle. We propose to alternately develop boosters with solid and liquid fuel, much larger than those currently in development, until it is certainly the best. We propose additional funds for the development of other engines and for unparalleled explorations that are particularly important for a purpose that this nation will never neglect: the survival of the man who will first make this bold flight. But in a sense, it will not just be a man to go to the moon – we express this judgment favorably, it will be an entire nation. Because we all have to work to bring it to us. ” |

On September 12, 1962, Kennedy held another speech in front of an audience of about 40 000 people at the American football stadium of the Rice University in Houston, Texas. [13] [14] A piece of the speech that is often mentioned is as follows: [15]

| ( IN )

«There is no strife, no prejudice, no national conflict in outer space as yet. Its hazards are hostile to us all. Its conquest deserves the best of all mankind, and its opportunity for peaceful cooperation may never come again. But why, some say, the Moon? Why choose this as our goal? And they may well ask, why climb the highest mountain? Why, 35 years ago, fly the Atlantic? Why does Rice play Texas? We choose to go to the Moon! We choose to go to the Moon…We choose to go to the Moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win, and the others, too.» |

( IT )

“There is still no struggle, no prejudice, no national conflict in space. His dangers are hostile to all of us. His conquest deserves the best of all humanity, and his opportunity for peaceful cooperation may no longer come. But why, says someone, the moon? Why choose it as our destination? And could they also ask, why climb the highest mountain? Why, 35 years ago, fly over the Atlantic? Why does Rice play for Texas? We choose to go to the moon! We choose to go to the moon … we choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are difficult; Because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that is a challenge that we are willing to accept, one that we are not willing to postpone and one that we intend to win and also the others. ” |

Nonetheless, the proposed program met the opposition of many US and was nicknamed a moondoggle (Word game with boondoggle , which means a waste of time and money) from Norbert Wiener, a mathematician from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. [16] [17] The effort to land a man on the moon already had a name: Apollo program. [18] When Kennedy met Nikita Chruščëv, the leader of the Soviet Union in June 1961, he proposed him to make the joint project a joint project but Chruščëv did not accept the offer. [19] Kennedy again proposed a joint shipping for the Moon in a speech at the United Nations General Assembly on September 20, 1963. [20] The idea of joint lunar mission was abandoned after Kennedy’s death. [21]

An initial and crucial decision, announced by James Webb on June 11, 1962, was the adoption of the Lunar Orbit Rendezvous, according to which a dedicated spacecraft would have landed on the lunar surface. This allowed to have a smaller launch vehicle. [22] [23] The Apollo spacecraft would therefore have been made up of three parts: a command module (cm) with a pressurized cabin for the three astronauts who was also the only part that returned to Earth; a service module (SM), which served as a support for the control module with a propulsion supply, electricity, oxygen and water; And a lunar module (LM) which in turn was divided into two stadiums: one for the descent and landing on the moon and a skiing stage to bring the astronauts back to the lunar orbit. [24] The choice of this mission profile meant that it was possible to launch the space vehicle through the Saturn V rocket, a carrier that was at the time being developed. [25]

The technologies and techniques required for Apollo were developed during the Gemini program. [26] The Apollo program suffered a sharp braking following the fire that incurred at Apollo 1, which took place on January 27, 1967, in which the three astronauts died and because of the subsequent investigations. [27] In October 1968, the Apollo 7 mission test the control module in Earth orbit [28] And in December Apollo 8 brought him to lunar orbit. [29] In March 1969, Apollo 9 performed the tests of the lunar module in terrestrial orbit, [30] And subsequently, in May 1969, Apollo 10 led a “general test”, testing the lunar module in lunar orbit. In July 1969, everything was ready for Apollo 11 and to take the last step on the moon. [thirty first]

The Soviet Union was responsible with the United States in the race to space, but lost its command after repeated failures in the development of the launcher N1, the Soviet consideration of the Saturn V. [32] The Soviets tried to beat the United States by reporting lunar material on earth by means of human -free probes. On July 13, three days before the launch of Apollo 11, the Soviets launched Luna 15, who reached the lunar orbit before Apollo 11. During the descent, Luna 15 crashed into the Mare CrisiUM due to a malfunction; This crash took place two hours before Armstrong and Aldrin took off from the lunar surface to return home. The radiotelescopi of the Jodrell Bank Observatory in England recorded Luna 15 broadcasts during his descent, which were made public in July 2009 on the occasion of the 40th anniversary of the Apollo 11. [33]

Crew [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

On November 20, 1967, the initial reserve crew of Apollo 9 was officially announced, composed of the commander Neil Armstrong, a cm Jim Lovell pilot and the LM Buzz Aldrin driver. [34] Lovell and Aldrin had previously flown in Gemini 12 together. Due to delays in the design and construction of the lunar module, Apollo 8 and Apollo 9 exchanged the main and reserve crew, so the armstong crew became the reserve for Apollo 8. Based on the usual crew rotation scheme, Armstrong was expected to command Apollo 11. [35]

There would have been a change. Michael Collins, the cm pilot in the apotel 8 crew, had leg problems. In fact, bone growth had been diagnosed between the fifth and sixth vertebra, which needed surgery. [36] Lovell then took his place in Apollo 8 and, when Collins recovered, entered the crew of Armstrong as a pilot of the command module. Meanwhile, Fred Haise and Aldrin took over respectively as pilots of the LM, and cm in the reserve crew of the Apollo 8. [37] Apollo 11 was the second US mission in which all crew members had space flight experiences; [38] The first was Apollo 10 [39] And the next would have been STS-26 in 1988. [38]

Slayton gave Armstrong the possibility of replacing Aldrin with Lovell, since some thought it was difficult to work with Aldrin. Armstrong had no problem working with Aldrin, but he thought about it for a day before refusing. He thought that Lovell deserved to personally command a mission (that Apollo 13 would have been). [40]

The crew of Apollo 11 was not characterized by a sense of joyful friendship, as was the case for Apollo 12, but rather that of a friendly work relationship. Armstrong was known to be particularly detached, but Collins, who considered himself solitary, confessed that he had rejected Aldrin’s attempts to create a more personal relationship. [41] Aldrin and Collins defined the crew members as “unknown friendlies”. [42] Armstrong did not agree with this statement and would later say that “[…] all the crews in which I was worked very well together”. [42]

Reserve crew [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

The reserve crew was composed of Lovell as a commander, Anders as a cm driver and Haise as a pilot of the LM. Anders and Lovell had flown together in Apollo 8. [38] At the beginning of 1968, Anders accepted a job at the National Aeronautics and Space Council, who would start in August of that year and announced that he would resign as an astronaut from that moment. Ken Mattingly was transferred from the CM pilot training supporting of the CM pilot in parallel with Anders in the event that Apollo 11 had been postponed, because Anders would no longer have been available. Lovell, Haise, and Mattingly would have constituted the crew of Apollo 13. [43]

Support crew [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

For each mission of the Mercury and Gemini programs, a main crew and one of the reserve was appointed. For the Apollo program, a third team of astronauts was added, known as support crew. These were delegated to the drafting of the flight plan, control lists and the basic procedures of the mission. In addition, they were responsible for ensuring that the astronauts of the main crew and reserve were informed of any changes. The support crew developed the procedures in the simulators, in particular those dedicated to dealing with emergency situations, so that the main and reserve crews could be coached with the simulators, allowing them to practice and master them. [44] For Apollo 11, the support crew was composed of Ken Mattingly, Ronald Evans and Bill Pogue. [45]

Communicators [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

The Communicator capsule (Capcom) was an astronaut at the Mission Control Center in Houston, Texas, who was the only person who communicated directly with the crew in flight. [forty six] Per l’Apollo 11, i CAPCOM erano Charles Duke, Ronald Evans, Bruce McCandless II, James Lovell, William Anders, Ken Mattingly, Fred Haise, Don L. Lind, Owen K. Garriott e Harrison Schmitt. [45]

Flight directors [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

The flight directors for this mission were: [47] [48] [49] [50] [51] [52]

Call codes [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

At the crew of the Apollo missions the possibility of renamed the ships in use was left, but, after the crew of the Apollo 10 had opted for Charlie Brown and Snoopy to identify respectively the command module and the lunar module, the vice Director of Public Relations, Julian Screer, wrote to George M. Low, director of the Mission Control Center, to suggest at the crew of the Apollo 11 more “serious” names. During the planning of the mission, the names were used in both internal and external communications Snowcone e Haystack To indicate the CM and LM respectively. [53]

The command module was so called Columbia , as well Columbiad , the gigantic cannon that, in Jules Verne’s novel From the earth to the moon (1865), shot the spacecraft towards the moon; He also referred to Columbia, a historical name of the United States. [54] [55] [56] The Lem instead was called Eagle ( Aquila ), the bird symbol of the United States, also represented on the mission emblem.

Mission emblem [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

The emblem of the mission was conceived by Collins, who wanted to symbolically represent a “peaceful warning of the United States”. He then represented a calm eagle, with an olive branch in the beak, which landed on a lunar landscape and with a view of the earth in the distance. Some NASA officials believed that the claws from L’Aquila seemed too “belligerent” and after some discussion, the olive branch was moved to the claws. The crew chose not to use the Roman number “XI”, but preferred to use the Arabic “11”, fearing that the former could not be understood in some nations. Furthermore, they chose not to indicate their names on the emblem, so that it was “representative of all those who had worked to allow the mission”. [57]

All colors are natural, with edges in blue and golden yellow. [58]

Souvenir objects [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

Astronauts had gods personal preference kit (PPK), small bags containing objects of personal emotional value that wanted to take with them on a mission. [59] Five PPK were brought to Apollo 11: three (one for each astronaut) were put on the Columbia , and two on Eagle . [60]

Neil Armstrong, in his personal preference kit (PPK) he wanted to keep a piece of wood from the left propeller of the Wright Flyer, the airplane of the Wright brothers of 1903, and a piece of fabric from the wing. [sixty one] He also had with him the distinctives of astronaut, enriched with diamonds, originally donated by Deke Slayon to the widows of the crew of Apollo 1. [62]

Choice of the Alunaggio site [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

The NASA commission in charge of the choice of the Alunaggio site (Apollo Site Selection Board) announced, on February 8, 1968, to have identified five potential. These were the result of two years of studies based on high resolution photographs of the lunar surface acquired by five crew -free probes of the Lunar Orbiter program and on the analysis of the information, learned during the Surveyor program, concerning the ground conditions. [63]

Not even the most performing terrestrial telescopes were able to view the characteristics of the moon’s surface with the resolution required by the specifications of the Apollo program. [sixty four] The areas that appeared clear and eligible for the Alununaggio on the photographs taken by the earth, were then often considered totally unacceptable. The original requirement was that the chosen site was without craters but had to be made less stringent, as no place had been found with these characteristics. [65] The five sites taken into consideration were: the 1 and 2 sites located in the sea of tranquility (Mare Tranquitatis), site 3 in the Sinus Medii and the 4 and 5 sites that are found in the ocean of storms (Oceanus procellarum). [63]

The selection of the final site was based on seven criteria:

- The site was to be flat, with relatively few craters;

- With free approach paths from large hills, high cliffs or deep craters who could have confused the landing radar and induce him to issue incorrect readings;

- reachable with a minimum quantity of propellant;

- taking into account the delays in the countdown of the launch of the Saturn V;

- By providing the space spacecraft Apollo a free return trajectory, that is, that it allowed to turn around the moon and return safely to Earth without requiring any lighting of the engine, in the event that a problem had arisen during the journey to the moon;

- With good visibility during the landing, which meant that the sun would have to be found between 7 and 20 degrees behind the lunar module;

- and with a general slope of less than 2 degrees in the landing area. [63]

The requirement of the sun angle was particularly restrictive, limiting the launch date one day a month. [63] In the end, the Apollo Site Selection Board selected site 2, with sites 3 and 5 as backup In case of delay in the launch. In May 1969, Apollo 10 flew less than 15 km from site 2 and reported that it was acceptable for the subsequent habit. [66]

Decisions on the first step [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

During the first press conference after the announcement of the crew of Apollo 11, the first question asked by a journalist was: “Who of you gentlemen will be the first man to set foot on the lunar surface?” [sixty seven] [68] Slayon replied that a decision had not yet been made, and Armstrong added that “it was not based on personal desires”. [sixty seven]

One of the first versions of the checklist on the exit provided that the pilot of the lunar module should come out before the commander; This agreed with the procedure followed in the previous missions. [69] The commander had never made a space walk. [70] At the beginning of 1969, journalists wrote that Aldrin would be the first to walk on the moon, and also George Mueller, Nasa’s associated administrator, said this. Aldrin infuriated himself, after he heard that Armstrong would be the first to set foot on the moon, because he was a civilian. Aldrin tried to convince other pilots of lunar modules of the fact that he should have been the first, but responded in a cynical way and considered it a lobbyism campaign. In an attempt to stop a conflict between the departments, Slayton told Aldrin that Armstrong would have been the first as commander. The decision was announced in a press conference on April 14, 1969. [71] Aldrin believed for decades that the final decision was largely depended on the position of the trapquis of the lunar module. Since the astronauts had worn their suits and the vehicle was small, moving to go out was difficult. The crew felt a simulation in which Aldrin was the first to leave the vehicle, and damaged the vehicle during the exit. Although this was sufficient for the organizers of the mission to make the final decision, Aldrin and Armstrong were kept in the dark about the verdict until late spring. [72] Slayon told Armstrong that the plan provided that he was the first to leave the vehicle if he agreed. Armstrong replied, “Yes, that’s how it is done.” [seventy three]

The media accused Armstrong of having exercised his position as commander to exit first. [74] Chris Kraft revealed in his autobiography that there was a meeting between him, Gilruth, Slayton and Low to make sure that Aldrin would not be the first to walk on the moon, because they believed that the first person had to be like Charles Lindbergh, a calm and peaceful person . They decided to change the flight program in such a way as to bring out the commander first. [75]

The rise stage of the LM-5 lunar module arrived at the Kennedy Space Center on January 8, 1969, followed four days later from the descent one; The CM-107 Command and Service form, however, arrived on January 23. [76] There were some differences between the LM-5 and the LM-4 that had flown in the Apollo 10 mission. First of all, the LM-5 possessed a VHF radio antenna to facilitate communication with astronauts during their extraveicular activity on the lunar surface; It was, then, a lighter skiing engine was present, greater thermal protection in the legs of the landing trolley and a series of tools for scientific experiments known as Early Apollo Scientific Experiments Package (EASEP). As for the command module, the only change in the configuration was the removal of an isolation from the front hatch. [77] [78] The command and service modules were assembled together on January 29 and thus moved on April 14 from the Operations and Checkout Building to Vehicle Assembly Building. [76]

In the meantime, on February 18, the third S-IVB stadium of the Saturn V As-506 had made its arrival, followed by the second S-II stadium on February 6, the first S-IC stadium on February 20 and the Saturn V Instrument Unit February 27th. At 12:30 on 20 May, the whole assembly complex of the total weight of 5,443 tons left, at the top of the Crawler-Transporter, the Vehicle Assembly Building in the direction of the launch platform 39a, part of the launch complex 39; At the same time Apollo 10 was traveling to the moon. On June 26, an countdown test began, which ended on July 2nd. The launch complex began to be illuminated on the night of July 15, when the Crawler-Transporter had now reached its parking lot ready for the launch. [76] In the early hours of the morning, the fuel tanks of the S-II and S-IVB stadiums were filled with liquid hydrogen. [79] The supply was then completed three hours before take -off. [80] The launching operations were partially automated, thanks to 43 programs written in the ATOLL language (Acceptance, Test or Launch Language). [81] [82]

The astronaut of the reserve crew Fred Haise entered the command module Columbia About three hours and ten minutes before the launch, together with a technician, to help Armstrong to take their seats, at 06:54 on the left seat. Five minutes later the commander was reached by Collins who occupied his position on the right seat. In the end, Aldrin also entered, sitting in the central place. [80] Haise left the shuttle about two hours and ten minutes before the launch. [83] Subsequently, the team of technicians closed the hatch and the cabin was pressurized, then left the launch complex about an hour before the time scheduled for take -off. The countdown became automatic three minutes and twenty seconds before launch. [80] More than 450 people were present, at that moment, at the command paintings of the Launch Control Center. [79]

The launch and the journey to the moon [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

It is estimated that about a million spectators have witnessed live at the launch of the Apollo 11 crowding the highways and beaches close to the launch site, while about 650 million attended the launch by television. Among the notables present there was the Chief of Staff of the United States Army, General William Westmoreland, four government members, 19 state governors, 40 mayors, 60 ambassadors and 200 members of the congress. Vice -president Spiro Agnew followed the event together with the former president, Lyndon B. Johnson and his wife Lady Bird Johnson. [79] [84] There were also around 3,500 media representatives, [85] of which about two thirds came from the United States and the remainder from 55 other countries. The launch was broadcast live on television in 33 countries, with an estimate of 25 million spectators only in the United States. Millions of people all over the world listened to the various radio broadcasts. [79] [84] President Richard Nixon followed the launch from his office to the White House in the company of his connection with NASA, the astronaut Frank Borman, commander of the Apollo 8 mission. [eighty six]

Apollo 11 was launched by a Voururn V carrier rocket from the launch platform 39a, part of the Kennedy Space Center launch complex 39, on July 16, 1969 at 13:32:00 UTC and entered Earth orbit twelve minutes later to An altitude of 185.9 km for 183.2 km. [eighty seven] After an orbit and a half, the PWR J-2 engine of the third S-IVB stadium pushed the shuttle on its trajectory to the Moon thanks to the Trans Lunar Injection (Tli) maneuver started at 16:22:13 UTC. About 30 minutes later the couple’s couple module/service module separated from the last stadium of the Saturn V and completed the maneuver to hook up to the lunar module still in its adapter placed at the top of the third stadium. After the lunar module was extracted, the combined spatial vehicle continued its journey to the moon, while the third stadium now abandoned was put in an eliocentric orbit, in order to prevent it from clashing with the shuttle with the astronauts or impact on the Land or on the moon. [88]

On July 19 at 17:21:50 UTC, Apollo 11 passed behind the moon and lit the engine on duty to enter the lunar orbit. In the thirty orbits [89] which carried out, the crew had the opportunity to observe the place scheduled for their landing in the south of the sea of tranquility (Mare tranquility) about 19 km south-west of the Sabine D crater (0.67408n, 23.47297e). The landing site had been chosen in part because it was considered having a relatively flat and smooth conformation thanks to the detections of the Ranger 8 and Surveyor 5 automatic probes and therefore did not have great difficulties in the Alununaggio and in the extraveicular activities. [90] The exact point chosen was located about 25 kilometers south-east of the Surveyor 5 landing site and 68 kilometers south-west of the Ranger 8 crash site. [91]

Descent to the moon [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

At 12:52:00 UTC of 20 July, Aldrin and Armstrong entered the lunar module ” Eagle “And the last preparations for the lunar descent began. [92] At 5:44:00 pm Eagle he separated from the command form ” Columbia “. [93] Collins, alone aboard the Columbia , inspected Eagle As he made a turn, in order to make sure that the shuttle was integrated and that the legs for landing were correctly deployed. [ninety four] [95] Armstrong, therefore, exclaimed: ” The Eagle has wings! “(” L’Aquila has wings! “). [95]

During the early stages of the descent, Armstrong and Aldrin noticed that they were exceeding the reference points on the lunar surface four seconds before expected and that therefore they were a little “long” providing that a few miles more west would be landed compared to their point of the expected wing. Eagle It was traveling, in fact, too fast. At first it was believed that this could have been caused by the mass concentration that would alter the trajectory. However, the flight director Gene Kranz hypothesized that the cause was the consequence of the turn of the turn carried out shortly before or the excess air pressure in the dock tunnel that had given an additional thrust not expected. [96] [97] In subsequent missions, the tunnel pressure was always ascertained before the release. [98]

After 5 minutes from the start of the descent, at 1800 m above the lunar surface, the navigation and driving computer of the lunar module attracted the attention of the crew with a series of alarms with code 1202 and 1201, belonging to the category “Executive alarm” That is, indicating that the driving computer was wasting resources in minor task and that memory risked overflow. The rest seemed to work correctly, which meant that it was task At low priority that the operating system was designed to ignore these conditions, then the specialists within the Mission Control Center of Houston in Texas, the engineer Jack Garman gave the authorization to proceed with the descent to the driving officer Steve Bales, who confirmed it to the crew (just a few days before the departure of the Bales mission had participated in a simulation that focused on the procedures to be followed in the event that an alarm 1202 was presented). [99] [100] [101] The cause of the alarms was diagnosed and attributed to the erroneous activation of the RR (Rendezvous Radar), formally not necessary during the descent. Margaret Hamilton, director of Apollo Flight Computer Programming At the Mit Draper Laboratory, he later recalled: [102]

| ( IN )

«Due to an error in the checklist manual, the rendezvous radar switch was placed in the wrong position. |

( IT )

«Due to an error in the checklist shown in a manual, the Rendezous radar switch had been set in a wrong position. This had caused the sending of misleading commands to the computer. The result was that the computer was asked to carry out all its normal landing operations, also receiving an additional load of spurious data to be tried, which however had consumed 15% more than its resources. The computer (more precisely, his software), recognized that he had been asked to carry out more task than those who would have to perform. He then warned the situation with an alarm, which for the astronauts had to be interpreted as “I am overloaded with more task than I should carry out at this moment, I will keep only the important ones active (for example those necessary for landing)”. […] In fact, the computer had been scheduled to make much more than recognize possible cases of errors. A complete series of restoration programs had been included in the software. The action of the software, in this case, was to exclude the low priority tasks and restore the most important ones. The computer, instead of causing an interruption, prevented it. If the computer had not recognized this problem and launched the appropriate restoration actions, I doubt that the wing of apollo 11 would be successful. ” |

| ( Margaret H. Hamilton, Computer Got Loaded (Letter), in Datamation , Cahners Publishing Company, March 1, 1971, ISSN 0011-6963 . ) | |

In fact, the checklist and the procedure followed were correct, since the Rendezous radar had to be maintained operational in the event of cancellation of the mission. As illustrated in 2005 by Don Eyles, a member of the MIT software development team, the anomaly occurred due to a design defect in the electronic interface system at the radar, for which a random electrical feed between two parts of the radar He mistakenly made the driver’s computer that the antenna swing and forcing it to continually recalculate the position. This generated cycle stealing additional spuries, which updated unnecessary meters, thus triggering the alarm. The defect had already been identified during the Apollo 5 mission but underestimated and incorrect. [103] [104]

During this phase, the astronauts were noticed that the Alunaggio website was much more rocky than the photographs had indicated. Armstrong therefore took the semi-manual control of the lunar module. [105]

Wing [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

When Armstrong had the opportunity to look again on the outside, he could see that the place of the landing proposed by the computer was in an area scattered with boulders and located near a cracrete of 91 meters in diameter (which took the name of Crater West ). Armstrong, therefore, took control of the shuttle in semi-automatic mode. [106] [107] Initially Armstrong thought of landing near the area with the boulders in such a way as to collect geological champions, but it did not succeed for the too high horizontal speed. During the descent, Aldrin reported the navigation data to Armstrong, who was busy piloting Eagle . At 33 meters above the surface, Armstrong knew that the propellant began to be scarce, so he was trying to land as soon as possible. [108]

Armstrong found a plot of free land and directed the vehicle there. 30 meters from the surface, they remained them available to them only for another 90 seconds. The engine of the Lem raised dust which began to cloud the view. From this cloud of dust came out of the rocks, and Armstrong took them as a reference during the descent to determine the movement of the vehicle. [109]

A few moments before the Alununaggio, a bright indicator informed Aldrin that at least one of the 170 cm probes that dangled from the landing legs of the Eagle He had touched the surface, and said: ” Contact light! “(” “Contact light!”). In theory Armstrong should have turned off the engine immediately, since the engineers suspected that the pressure caused by the exhaust that bounced on the lunar surface would cause an explosion, but it forgot. later, Eagle He was Equal and Armstrong said ” Shutdown “. [110] Aldrin immediately replied “Ok, engine arrest. Acca – out of detent “” Armstrong confirmed: ” Out of detent . Auto “. Aldrin continued:” Control mode, both set on Automatic, disabled descent engine control, the engine off. 413 Posted “. [111]

ACA was the Altitude Control Assembly, the LEM cloche; This sent the signal to the LM Guidance System (LGC) to check the Reaction Control System (RCS). ” Out of detent “It means that the cloche was moved from the central position; like the indicators of the cars of the cars, a spring showed it to the center. Address 413 of the LGC contained the variable that indicated the wing of the Lem. [105] The control methods available were PGNS (Primary Guidance) and AGS (Abort Guidance).

| ( IN )

«Houston, Tranquility Base here. The Eagle has landed.» |

( IT )

«Houston, the basis of tranquility here. Eagle has landed ” |

| ( Historical phrase of Neil Armstrong a few seconds after the lunar module landing. [105] ) | |

Eagle He had settled on the lunar surface at 20:17:40 UTC on Sunday 20 July, with only about 25 seconds of fuel still in the tanks according to the on -board tools [105] . However, post mission analyzes established that it was probably still present fuel for about 50 seconds. The Apollo 11 therefore landed with less fuel than the subsequent missions, and the astronauts had an early notice of lack of fuel. It was later discovered that it was the result of a movement of fuel inside the tanks, which had “exposed” and activated the relative sensor. In the following missions, bulkheads were inserted in the tanks to prevent this event. [105]

Armstrong confirmed the completion of the checklist Aldrin post-cotterragging with ” Engine arm is off “, before responding to Capcom, Charles Duke, with the words” Houston, the basis of tranquility here “. The change of the call code of Armstrong from” Eagle “A” base of tranquility “(” Tranquility Base “) He underlined to the listeners that the wing had successfully taken place. Duke, he erroneously pronounced the beginning of the answer while expressed the relief of the mission control:” Roger, Twan Tranquility, we confirm your landing, here we were about to become all blue from the fright, we are now resuming to breathe, thank you very much. ” [105] [112]

Two and a half hours after landing, before the preparations for Eva began, Aldrin transmitted via radio to Earth: [113]

| ( IN )

«This is the LM pilot. I’d like to take this opportunity to ask every person listening in, whoever and wherever they may be, to pause for a moment and contemplate the events of the past few hours and to give thanks in his or her own way. Over.» |

( IT )

“Here is the Lem pilot. I would like to take this opportunity to ask every person you listen to, anyone and wherever you are, to stop a moment and contemplate the events of the last hours and thank in his own way. Step.” |

| ( Buzz Aldrin ) | |

So, privately, he participated in the sacrament of the Holy Supper, with bread and wine prepared specifically. At that time, NASA was still involved in a cause understood by Atea Madalyn Murray O’hair (who had criticized the reading of Genesis by the crew of Apollo 8) and therefore asked its astronauts to refrain from transmitting religious activities while they were in space. Thus, Aldrin chose to refrain from mentioning this act directly. Aldrin was a member of the presbyterian church of Webster, and his set for the Holy Supper was prepared by the church shepherd. That church still has the chalice used on the moon and every year commemorates the event on Sunday closest to July 20. [114] The mission program provided that the astronauts, after the wing, watched a five -hour sleep period, however they decided to start the preparations for Eva immediately, believing that they would not be able to sleep, if they are provided in the phase flight planning. [115] [116]

Operations on the lunar surface [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

According to the program, Armstrong and Aldrin after having completed all the expected checks should have rest for a few hours inside the lunar module, possibly helped to sleep with tranquilizers, then they would have prepared for the exit, scheduled for 6:17 UTC (8:17 Italian). [117] Instead the astronauts did not sleep. At 10:12 pm UTC (0:12 Italian) Armstrong communicated the decision to proceed with the preparation of the first extraveicular activity, instead of resting, with these words: “Our advice at this point is to plan the extraveicular activity, with the Your approval, starting from eight tonight, Houston’s hour. Approximately in three hours “. [118] Dr. Berry, the doctor who controlled the conditions of Armstrong with telemetry, said he agreed, and so also the flight director Cliff Charlesworth, and from Houston the ok was given. [119]

The preparations for the lunar walk began at 11:43 pm [93] requiring more time than expected: three and a half hours instead of two. [120] During training on Earth, everything needed had been prepared in advance, but on the moon the cabin of the lunar module also contained a large number of other objects, such as control lists, food packages and instruments. [121] Once Armstrong and Aldrin were ready to go out, the lunar module Eagle He was depressurized. [122] The hatch was therefore open at 02:39:33. [93] The astronaut had some initial difficulties in leaving the counter because of his PLSS (Primary Life Support System, the backpack hooked to the space suit). [123] In fact, according to the lunar veteran John Young (American astronaut), to a redesign of the LM which provided for a smaller counter, did not follow a revision of the PLSS, so the entry and exit of the astronauts from the counter was difficult. Some of the highest cardiac frequencies recorded by the astronauts of the Apollo missions were found during the exit and entry from the LM. [124] At 02:51 Armstrong began his descent towards the lunar surface through the ladder, however he had a certain difficulty due to the fact that the remote control unit placed on the helmet prevented him from seeing his feet. While the nine -sided ladder descended, Armstrong pulled the D ring that sided the Modular Equipment Stowage Assembly (MESA) against the side of the Eagle activating the camera for television. [first] [125]

The installed camera of Apollo 11 used a slow scan television recovery, incompatible with the normal television broadcast, so the image had to be viewed on a special monitor where it was in turn taken by a conventional camera, however significantly reducing quality. [126] The first images were received at the Goldstone Deep Space Communications Complex in the USA, but those with best definition saw HoneySuckle Creek in Australia. A few minutes after the audiovisual flow it was diverted to the most receptive radio and telescope of the Parkes Observatory in Australia [127] . Thus, despite the initial difficulties, the first black and white images of a man on the moon were seen live by at least 600 million people scattered all over the world. [127] Copies of this video are widely available, but the recordings of the original transmission of the slow scan source from the lunar surface were probably destroyed during the normal reuse of the magnetic tape at NASA. [126]

While he was still on the lineup, Armstrong discovered a plaque mounted on one leg of landing of the LM on which two drawings of the Earth were engraved (of the western and eastern hemispheres), an inscription and the signatures of the astronauts and the Nixon president. [first] Six and a half hours after touching the ground, at 2:56:15 UTC (4:56 Italian), after a brief description of the surface ( very fine grained… almost like a powder that is “very fine grain … almost like dust” [first] ) and pronounced his historic phrase, Armstrong took his first step out of Eagle and became the first man to walk on another celestial body.

| ( IN )

«That’s one small step for [a] man, but [a] giant leap for mankind.» |

( IT )

“This is a small step for a man, but a great leap for humanity.” |

| ( Neil Armstrong; ) | |

Armstrong meant “That’s one small step for a man”, but the article “A” was not audible in the transmission, therefore initially it was not reported by most of the observers of the live. Without the article, the phrase is translatable as “this is a small step for the man” instead of “for a man”. [128] When he was subsequently asked about the phrase, Armstrong said he believed he had said “for a man”; Since then the subsequent printed versions have included the “A” in square brackets. The absence of the word can be explained by its emphasis, or by the intermittent audiovisual connection; In part also for storms near the Parkes Observatory. Recent digital analyzes seem to demonstrate that the “A” may have been pronounced but covered by the static. [129] [130] [131]

In addition to being the concretization of John F. Kennedy’s dream to see a man on the moon before the late sixties, Apollo 11 was a test for all the next missions Apollo; Then Armstrong took the photos that would serve the technicians on Earth to check the conditions of the lunar module after the wing.

About seven minutes after walking on the moon’s surface, Armstrong collected a land of land. As soon as he had done it, he folded the container where he had placed him and put it in a pocket of the suit on the right thigh. He made this to ensure that some lunar ground was however reported in the event that an emergency requires astronauts to abandon the walk. [132] Twelve minutes after collecting the sample, [133] Removed the camera from the Mesa, made a panoramic recovery and then installed it on a tripod. [120] The cable of the television camera remained partially rolled up, leading to astronauts a risk of stumbling for the duration of the extra vales. The photographs were taken with a Hasselblad camera that could be used both by hand and mounted on the Apollo/SkyLab A7L spaces of Armstrong. [134] Shortly afterwards he was reached on the surface by Aldrin who commented: “Magnifica desolation”. [123]

Armstrong observed that moving in the lunar gravity, a sixth of the terrestrial one, was “perhaps easier than the simulations … it is absolutely not a problem going around”. [first] Aldrin test the best methods to move, including the so -called Kangaroo jump . The layout of the weights in the PLSS created a tendency to fall towards the back, but neither of the two astronauts had serious balance problems. Running with long steps became the method to move preferred by the two astronauts. Aldrin and Armstrong reported that they had to plan the movements to be taken six or seven steps before. The very fine soil was also particularly slippery. Aldrin pointed out that moving between direct sunlight and the shadow of Eagle It did not cause significant temperature changes within its space suit, instead the helmet was warmer in the sun. [first] The Mesa was unable to provide a stable work platform and was in the shade, slowing down the job a little. As they worked, the astronauts raised gray powder that dirty the external part of their suits. [134]

The astronauts planted the United States flag together, but the consistency of the ground did not allow it to insert it for more than a few centimeters. [135] Before Aldrin could take a photo of Armstrong with the flag, the astronauts received a call from the president of the time, Richard Nixon, who spoke to them through a radio-telephones transmission that he himself called “the most historic called never made by the White House” . [136] Originally Nixon had prepared a long speech to read during the call, but the astronaut Frank Borman, who was in the White House as a connection of NASA during Apollo 11, convinced him to say short words. [137]

They positioned the Easep, which included a passive seismograph (passive Seismic Experiment Package) and a retoreflector (device made up of multi-packed cells, oriented in order to reflect the light of a laser aimed from the earth towards the moon), used for the Lunar laser racing experiment. [138] Subsequently, Armstrong took great steps about 60 meters from the lunar module to photograph the eastern crater while Aldrin began the collection of lunar material. He used the geological hammer, and this was the only situation in which he was used by Apollo 11. The astronauts began the collection of lunar rocks with the palettes, but since the operation required much more time than expected, they were forced to abandon the I work in the middle of the 34 minutes planned. Aldrin managed to collect 6 kg of lunar sand in total. [139] Two types of rocks were found in the geological samples taken: basalt and breach. [140] The scientists also discovered three new minerals: Armalcolite, Tranquility and Pyroxferroite. Armalcolite takes its name from Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins. [141]

The Mission Control Center used a code phrase to warn Armstrong that its metabolic rates appeared high and that she should have slowed down the activity. In fact, we were moving quickly from one task to another while the weather exhausted. Since metabolic rates remained, throughout the space walk, however overall lower than expected for both astronauts, the mission control granted a 15 -minute extension. [142] In a 2010 interview, Armstrong explained that NASA had limited the time and distance of the first lunar walk since there was no certainty on how much cooling water they would consume the PLSS of the astronauts to manage their body temperature while working on the Moon. [143]

Columbia in lunar orbit [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

During his day spent alone around the moon, Collins actually never felt alone, although it has been said that “it is from Adam that no one has known such a human solitude”. [144] In his autobiography he wrote: “This company was structured for three men and I consider my role necessary as one of the other two”. [144] In the 48 minutes of each orbit, when he was out of the radio contact with the earth, while the Columbia He passed to the other side of the moon, the feeling he reported was not fear or loneliness, but rather “awareness, expectation, satisfaction, trust, almost exultation”. [144]

One of the first Collins tasks was to identify the lunar module on the ground. To give him an idea of where to look, the mission control communicated to him that he believed it was landed about four miles from the expected point. So, every time he passed beyond the suspected lunar landing site, he tried in vain to find the lunar module. During his first orbits on the rear side of the moon, Collins carried out maintenance activities, such as downloading the excess water produced by the fuel cells and preparing the cabin for the return of Armstrong and Aldrin. [145]

Just before it reached the dark side of the moon during the third orbit, the mission control informed Collins that there was a problem with the cooling liquid temperature. If it had become too cold, some parts of the Columbia They could therefore have frozen it was advised to take manual control and implement the procedure 17 of malfunction of the environmental control system. Instead, Collins again operated the automatic manual system switch and again automatically and continued with normal activities, constantly monitoring the temperature. When the Columbia He returned to the visible side of the moon again, reported that the problem had been solved. In the following two orbits, he described his time spent on the hidden side of the moon as “relaxing”. After Aldrin and Armstrong completed Eva, Collins slept in order to rest in view of appointment . While the flight plan required that Eagle we met with the Columbia , Collins had also been prepared if he should have reached the lunar module. [146]

Living from the moon [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

Aldrin returned to the Eagle first. With not a few difficulties, astronauts loaded the films and two bags containing more than 22 kg of lunar material from the moon module counter, thanks to a pulley system called Lunar Equipment Conveyor. This proved to be an inefficient tool and the subsequent missions preferred to bring the equipment and the champions to the lunar module by hand. [120] Armstrong reminded Aldrin an envelope of commemorative objects placed in the sleeve pocket and then Aldrin threw the bag down. Armstrong then climbed on the third peg of the lineup and entered the LM. After connecting to the vital support of the lunar module, the astronauts lightened the skiing stadium for the return to the lunar orbit, launching their PLSS backpacks, their lunar covers, an empty Hasselblad camera and other equipment. The hatch was closed at 05:01. Then they pressurized the form and prepared to sleep. [147]

Nixon’s speechwriter, William Safire, had prepared a contingency press release, entitled In Event of Moon Disaster , which should have read live on television in the event that the astronauts had been blocked on the moon. [148] The contingency plan originated in a memorandum To Safire for the head of Cabinet of the White House of Nixon, H. R. Haldeman, in which Safire suggested a protocol that the administration could have followed in reaction to such a disaster. [149] [150] According to the plan, the mission control would have “closed communications” with the Lem and a priest would have “praised the souls deep in the deep” in a public ritual comparable to the burial at sea. The last line of the prepared text was taken from a poem of the First World War written by the English poet Rupert Brooke called The Soldier (“The soldier”). [150]

While moving inside the LM cabin, Aldrin accidentally damaged the switch that would have armed the main engine for take -off from the moon. The use of a marker was sufficient to activate the switch; If this had not worked, the Lem circuit could have been reconfigured to allow the lighting engine to turn on. [147] Armstrong jealously kept that marker until the day of his death.

After about seven hours of rest, the crew was awakened by the Houston control center to prepare for the return. Two and a half hours later, at 17:54:00 UTC, they took off to reach Collins on board the Columbia in lunar orbit. [151] In addition to the scientific tools, the astronauts left on the lunar surface: a distinctive of the Apollo 1 mission in memory of the astronauts Roger Chaffee, Gus Grissom and Edward White, who lost their lives during a test due to a fire that broke out in the command module in January 1967; A commemorative bag containing a gold replica of an olive branch as a traditional symbol of peace and a disc containing the declarations of goodwill of the presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon together with the messages of the leaders of 73 countries around the world . [133] They also left an American flag and a plaque with the drawings of the two terrestrial hemispheres, an inscription, the signatures of the astronauts and the Nixon president. Registration reads:

| ( IN )

«HERE MEN FROM PLANET EARTH |

( IT )

«Here men from the planet earth |

Return to Earth [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

Eagle he made the rendezvous with the command module Columbia At 9:24 pm UTC of 21 July and hooked it at 9:35 pm. Then, the rise form of Eagle He was released in lunar orbit at 11:41 pm. [152] Just before the take -off of the Apollo 12 mission, the problem had been posed that Eagle He could still find himself in orbit around the moon, however the studies of NASA technicians indicated that his orbital trajectory had lapsed and the module had therefore crashed into an “uncertain position” of the lunar surface. [153]

On July 23, the last night before the return to Earth, the three astronauts held a television broadcast in which Collins commented: [154]

| ( IN )

«The Saturn V rocket which put us in orbit is an incredibly complicated piece of machinery, every piece of which worked flawlessly. […] We have always had confidence that this equipment will work properly. All this is possible only through the blood, sweat, and tears of a number of people. […] All you see is the three of us, but beneath the surface are thousands and thousands of others, and to all of those, I would like to say, ‘Thank you very much» |

( IT )

«[…] The Saturn V rocket that put us in orbit is an incredibly complicated machine, each piece has worked impeccablely […] We have always trusted that this equipment worked correctly. All this is possible only through the blood, sweat and tears of a number of people […] All we see we are three, but under the surface there are thousands and thousands of others, and to all these, I would like To say “thank you very much”. ” |

| ( Michael Collins ) | |

Aldrin added: [154]

| ( IN )

«This has been far more than three men on a mission to the Moon; more, still, than the efforts of a government and industry team; more, even, than the efforts of one nation. We feel that this stands as a symbol of the insatiable curiosity of all mankind to explore the unknown. […] Personally, in reflecting on the events of the past several days, a verse from Psalms comes to mind. ‘When I consider the heavens, the work of Thy fingers, the Moon and the stars, which Thou hast ordained; What is man that Thou art mindful of him?”» |

( IT )

«This has been much more than three men on a mission on the moon; More, again, than the efforts of a government and an industrial group; More, even, of the efforts of a nation. We feel that this represents a symbol of the insatiable curiosity of all humanity to explore the unknown … Personally, reflecting on the events of the last few days, I am reminded of a verse of the psalms. “When I consider the skies, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars, whom you ordered, what is the man you remember for him?” |

| ( Buzz Aldrin ) | |

Armstrong concluded: [154]

| ( IN )

«The responsibility for this flight lies first with history and with the giants of science who have preceded this effort; next with the American people, who have, through their will, indicated their desire; next with four administrations and their Congresses, for implementing that will; and then, with the agency and industry teams that built our spacecraft, the Saturn, the Columbia, the Eagle, and the little EMU, the spacesuit and backpack that was our small spacecraft out on the lunar surface. We would like to give special thanks to all those Americans who built the spacecraft; who did the construction, design, the tests, and put their hearts and all their abilities into those craft. To those people tonight, we give a special thank you, and to all the other people that are listening and watching tonight, God bless you. Good night from Apollo 11.» |

( IT )

«The responsibility of this flight lies above all in the history and with the giants of science that preceded this effort; Later with the American people, who have, through their will, indicated their desire; then with four administrations and their congresses, for the implementation of this will; And then, with the agency and the teams in the sector who built our spacecraft, Saturn, Columbia, Eagle and small EMU, the space suit and the backpack that was our small spaceship on the lunar surface. We would like to thank all the Americans who built the spacecraft in a particular way; Whoever did the construction, design, tests, and put their hearts and all their skills in those jobs. To those people tonight, we give special thanks, and to all the other people they are listening to and looking tonight, God bless you. Good night from Apollo 11. ” |

| ( Neil Armstrong ) | |

Kick and quarantine [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

On June 5, the aircraft carrier was chosen, under the command of Captain Carl J. Seiberlich, under the command [155] As the main recovery ship (PRS) for Apollo 11, to replace its twin ship, the USS Princeton, who had recovered Apollo 10 on May 26. At that moment the Hornet He was moored in his port in Long Beach, California. [156] Arrived in Pearl Harbor on 5 July, the Hornet embarked the Sikorsky SH-3 Sea King helicopters of the Helicopter Sea Combat Squadron Four, a unit specialized in the recovery of Apollo space vehicles, specialists of the Apollo detachment of the Underwater Demolition Team, a team recovery of the NASA of 35 men and about 120 media representatives. To make space, most of the Hornet’s aerial wing was left in Long Beach. Special recovery devices were also loaded, including a fake model of the command module to be used for training. [157]

On July 12, with Apollo 11 still on the launch ramp, the Hornet left Pearl Harbor to head to the recovery area in the central Pacific [158] near 10°36′N 172 ° 24′e / 10.6 ° n 172.4 ° e . [159] A presidential representation, made up of Nixon, Borman, the secretary of state William Pierce Rogers and the national security councilor Henry Kissinger flew with Air Force One on the Alto Johnston, then on the USS Arlington command ship with the Marine One. After a night on board, always with the Marine One, they reached Hornet. Their arrival aboard the Hornet was greeted by the commander of the Pacific (Cinpac), by Admiral John S. McCain Jr. and by the administrator of Nasa Thomas O. Paine. [160]

At the time, meteorological satellites were not yet widespread, but captain Hank Brandli of the US Air Force had access to the images top-secret of spy satellites. Thus, he realized that a temporal front was directed towards the recovery area. The poor visibility represented a serious threat to the mission; If the helicopters had not managed to locate the Columbia , the spacecraft, its crew and its invaluable load of lunar rocks could have been lost. Brandli warned the navy captain Willard S. Houston Jr., commander of the meteorological center of the fleet in Pearl Harbor. On their recommendation, the recipient Donald C. Davis, commander of the recovery forces in the Pacific, advised NASA to change the recovery area and thus was done, designating a new one [161] 398 km north-east of the original. [162]

Before the dawn of 24 July, four Sea King helicopters and three Gumman E-1 Tracer took off from the Hornet. Two of the E-1s were designated as ” air boss “While the third served as a plane for communications. Two of the Sea Kings transported the divers and equipment for the recovery, the third photographic equipment and the fourth the diver in charge of the decontamination and the flight doctor. [163] At 16:44 UTC (18:44 local time) the parachute paraphreno of the Columbia They opened, as observed by helicopters. Seven minutes later, the shuttle impacted the water at 2,660 km east of the Wake island, 380 km south of the Alike Johnston and 24 km from the Hornet recovery ship, [152] [162] precisely 13°19′N 169 ° 09′W / 13.316667°N 169.15°W . [164] In placing, the Columbia The command module found itself upside down, but in just 10 minutes it was put back in the right position thanks to the floats open by the astronauts. “Everything is fine, our control list is complete, we wait for the divers”, it was the latest official transmission of Armstrong from Columbia . [165] A diver from the sea helicopter who found himself above them attacked an anchor to the command module to prevent him from drifting. [166] Additional floats were attached to the shuttle to stabilize it and the rafts were positioned for the extraction of astronauts. [167]

The divers provided with astronauts of the biological isolation clothing they wore until they reach the insulation chambers on board Hornet. In addition, the astronauts were rubbed with a sodium hypochlorite solution and the clean control module with Betadine to remove any lunar powder that could have been present. The raft containing the decontamination materials was therefore intentionally sunk. [168]

A second Sea King helicopter (the famous helicopter 66) took the astronauts one by one, and a NASA flight doctor did everyone a short physical control during the trip to return to Hornet. Arriving on the aircraft carrier, the astronauts left the helicopter, leaving the flight doctor and the three crew members, to head to the Quarantine Facility Mobile (Mqf) where their 21 days of quarantine began. This practice continued for two other Missions Apollo: Apollo 12 and Apollo 14, before the absence of any risk of transport of infectious agents from the moon was definitively demonstrated. [168]

President Richard Nixon was aboard Hornet to personally welcome the astronauts on earth to which he said: “As a result of what you did, the world has never been closer”. [169] After Nixon left, the Hornet was combined with the command module that was hoisted on the edge and placed near the square meters. Hornet sailed to Pearl Harbor where the command module and the square meter were transported by plane to Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center. [168]

According to the extra-terrestrial exposure law, the astronauts were quarantine for fear that unknown pathogenic organisms could be on the moon to which they could have been exposed during their extraveicular activities. However, after almost three weeks of confinement (first in the square meters and subsequently in the Lunar Receiving Laboratory), the astronauts did not accuse any symptom or sign of illness. [170] Thus, on August 10, 1969 they left the quarantine.

Celebrations [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

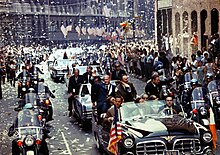

On August 13, the three astronauts were the protagonists of a Ticker-Tape Parade in New York and Chicago in which it is estimated that six million people participated. [171] [172] The same evening in Los Angeles there was an official state dinner, at the Century Plaza Hotel, to celebrate the flight, in the presence of members of the congress, 44 governors, the president of the Supreme Court of the United States of America and ambassadors of 83 nations . Nixon and Agnew decorated every astronaut with the presidential freedom medal. [171] [173]

Subsequently, on September 16, 1969, the three astronauts held an intervention during a joint session of the congress. On this occasion they gave two US flags, one to the room of representatives and the other to the Senate, who had been brought to the lunar surface with them. [174] A flag of the American Samoa who flew on Apollo 11 is now exhibited at the Jean P. Haydon Museum of Pago Pago, the capital of the American Samoa. [175]

These celebrations were the beginning of a 38 -day world tour, from September 29 to November 5, which brought astronauts to 22 foreign countries where they had meetings with the leaders of many countries. [176] [177] [178] Many nations have honored the first human landing of the moon with special numbers of the magazines or by emitting stamps or commemorative coins of Apollo 11. [179]

[ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

The command form Columbia He was brought around the United States, visiting 49 state capitals, the Columbia and Anchorage district in Alaska. [180] In 1971 he was transferred to the Smithsonian Institution to be exhibited at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, DC [181] in the central room ” Milestones of Flight “In front of the entrance and together with other pioneering vehicles such as Wright Flyer, Lo Spirit of St. Louis, Bell X-1, North American X-15 and Friendship 7. [182]

In 2017 the Columbia He was temporarily transferred to the Hangar Mary Baker Engen Restoration at the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in Chantilly, Virginia for a tour that touched four cities and entitled Destination Moon: The Apollo 11 Mission. The tour included the Space Center Houston from 14 October 2017 to 18 March 2018, the Saint Louis Science Center from 14 April to 3 September 2018, the John Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh from 29 September 2018 to 18 February 2019 and the Museum of Flight of Seattle from March 16 to September 2, 2019. [183] [184]

For 40 years, the spatial suits of Armstrong and Aldrin were exhibited in the exhibition Apollo to the Moon , [185] Until the closure of the exhibition on December 3, 2018. The exhibition will be replaced by a new exhibition gallery that is expected to open in 2022. A special exhibition of the Armstrong suit is scheduled for the 50th anniversary of the mission that will have in July 2019. [186] The quarantine module, the floating collar and the floating bags are found in the Smithsonian branch, the Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center, near the Washington-Dulles International Airport in Virginia, where they are exhibited together with a lunar module used in the ground tests. [187] [188] [189]

The descent stadium of the form Eagle He stayed on the moon. In 2009, the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) photographed the various sites of the molasses of the Apollo missions; For the first time, the resolution was such as to distinguish the descent stadiums of the lunar modules, various scientific tools and the footprints of astronauts. [190] The ascension stage, after it was abandoned, crashed into a place of the lunar surface still unknown, since the trajectory of the stadium was not traced after the release and the lunar gravity is not uniform enough to allow an accurate forecast. [191]

In March 2012, a team of specialists financed by Jeff Bezos, founder of Amazon.com, locked the five F-1 engines of the Apollo 11. They were found in the Atlantic thanks to advanced Sonar scans. [192] [193] The team brought some parts of two of the five surface engines. In July 2013, a restorer discovered a serial number under the rust of one of the engines, which NASA confirmed to be of the apollo 11. [194] [195] The third stadium of the S-IVB that carried out the trajectory of lunar insertion of the Apollo 11 remains in an eliocentric orbit close to that of the Earth. [196]

Lunar rocks [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

The main place where the lunar rocks collected during the Apollo program are kept is the Lunar Sample Laboratory Facility located at the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center in Houston, Texas. However, for safety, a small quantity is also present in the White Sands Test Facility near Las Cruces, in the New Mexico. Most of the rocks are kept in nitrogen to keep them without humidity. Therefore they are analyzed only indirectly, using special tools. More than 100 research workshops all over the world lead studies on samples and about 500 samples are prepared and sent to researchers every year. [197] [198]

In November 1969, Nixon asked NASA to prepare about 250 lunar powder samples collected by Apollo 11 to be delivered in 135 nations, in the various states that form the Union and the United Nations as a gift of benevolence. The samples, size of a grain of rice, consisted of four small pieces of lunar ground weighing about 50 mg and were wrapped in a transparent acrylic capsule about a large use of US dollar. This capsule was able to enlarge the grains of lunar powder. [199] [200]

The passive seismic experiment left on the moon worked until the Uplink line stopped working on August 25, 1969, while on 14 December of the same year the same fate fell to that of Downlink. [201] At 2018, the Lunar Laser Ranging experiment was still operational. [202]

On 20 July 2004 NASA celebrated the 35th anniversary of the Alununaggio and the Apollo 11 mission with a great commemorative ceremony and with the meeting, the following day, of the astronauts still in life and the most important collaborators of the project at the White House with the Then President of the United States George W. Bush. [203]

Fortieth anniversary [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

Again on July 20, 2009, Armstrong, Aldrin and Collins were invited to the White House by President Obama, to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the Alhunaggio. [204] TV and newspapers dedicated the whole day to the heroes of the mission, and on the occasion of the anniversary a film-documentary was made that traces the history of the apotal, Moonshot . [205] At the White House, the three astronauts held a speech in which they invite the country to send the man to Mars.

Fifty anniversary [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

On June 10, 2015, Bill Posey, a member of the United States Congress, introduced the H.R. 2726 in the 114th session of the House of Representatives, which orders the United States Mint to conceive and sell commemorative coins plated in gold and silver on the occasion of the fifty -year -old from the Apollo 11 mission. On January 24, 2019, the United States Mint released the coins to public through its site. [206] On March 1, 2019, a documentary on Apollo 11 was released in Imax, with original filming of 1969 restored. This documentary was distributed in the United States on March 8, 2019 [207] [208] And it was distributed in Italy on 9, 10, 11 of September 2019. [209]

Hooks between the CSM-LM [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

- Separation: 20 July 1969, 17:44 UTC

- Raisted: July 21, 1969, 21:35 UTC

Moon walk [ change | Modifica Wikitesto ]

- Opening of the LM portel: July 21, 1969, 2:39:33 UTC

- Armstrong, EVA ( Extra-vehicular activity , extraveicular activities)

- Leaving LM: 2:51:16 UTC

- Contact with lunar soil: 2:56:15 UTC

- Return to LM: 5:09:00 UTC

- Aldrin, Eva

- Leaving LM: 03:11:57 UTC

- Contact with lunar soil: 03:15:16 UTC

- Return to LM: 05:01:39 UTC

- Closing of the LM portel: July 21, 05:11:13 UTC

- Duration: 2 hours, 31 minutes, 40 seconds

![]() This item includes material in public domain from the site or from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration documents.

This item includes material in public domain from the site or from the National Aeronautics and Space Administration documents.

- ^ a b c d It is f ( IN ) Eric M. Jones (edited by), One Small Step . are History.nasa.gov , Apollo 11 Lunar Surface Journal, NASA, 1995. URL consulted on 9 March 2019 (archived by URL Original February 10, 2019) .

- ^ ( IN ) Richard Stenger, Man on the Moon: Kennedy speech ignited the dream , in CNN , 25 May 2001 (archived by URL Original June 6, 2010) .

- ^ a b Logsdon, 1976, p. 134 .

- ^ Logsdon, 1976, pp. 13-15 .

- ^ Brooks, Grimwood e Swenson, 1979, p. 1 .

- ^ Swenson, Grimwood e Alexander, 1966, pp. 101-106 .

- ^ Swenson, Grimwood e Alexander, 1966, p. 134 .

- ^ Swenson, Grimwood e Alexander, 1966, pp. 332-333 .

- ^ Swenson, Grimwood e Alexander, 1966, p. 342 .

- ^ Logsdon, 1976, p. 121 .

- ^ Logsdon, 1976, pp. 112-117 .

- ^ ( IN ) Excerpt from the ‘Special Message to the Congress on Urgent National Needs’ . are nasa.gov , 11 April 2017. URL consulted on April 2, 2019 ( filed on February 8, 2019) .

- ^ Eugene Keilen, ‘Visiting Professor’ Kennedy Pushes Space Age Spending , in The Rice Thresher , September 19, 1962, p. 1. URL consulted on 11 March 2018 ( filed 11 March 2018) .

- ^ Jade Boyd, JFK’s 1962 Moon Speech Still Appeals 50 Years Later . are News.rice.edu , 30 August 2012. URL consulted on March 20, 2018 ( filed on February 2, 2018) .

- ^ John F. Kennedy Moon Speech – Rice Stadium . are Er.jsc.nasa.gov . URL consulted on March 10, 2018 ( filed March 13, 2018) .

- ^ ( IN ) Charles Fishman, What You Didn’t Know About the Apollo 11 Mission . are smithsonianmag.com . URL consulted on June 17, 2019 ( filed on 9 August 2019) .

- ^ ( IN ) Alexis C. Madrigal, Moondoggle: The Forgotten Opposition to the Apollo Program . are theaterlantic.com , 12 September 2012. URL consulted on June 17, 2019 ( filed on September 3, 2019) .

- ^ Brooks, Grimwood e Swenson, 1979, p. 15 .

- ^ Logsdon, 2011, p. 32 .

- ^ Address at 18th U.N. General Assembly . are jfklibrary.org , 20 September 1963. URL consulted on 11 March 2018 ( filed 11 March 2018) .

- ^ Andrew Glass, JFK Proposes Joint Lunar Expedition with Soviets, September 20, 1963 . are Politico.com , 20 September 2017. URL consulted on March 19, 2018 ( filed March 20, 2018) .

- ^ ( IN ) The Rendezvous That Was Almost Missed: Lunar Orbit Rendezvous and the Apollo Program . are nasa.gov . URL consulted on April 2, 2019 ( filed March 23, 2019) .

- ^ Swenson, Grimwood e Alexander, 1966, pp. 85-86 .

- ^ Brooks, Grimwood e Swenson, 1979, pp. 72-77 .

- ^ Brooks, Grimwood e Swenson, 1979, pp. 48-49 .

- ^ Brooks, Grimwood e Swenson, 1979, pp. 181–182, 205–208 .

- ^ Brooks, Grimwood e Swenson, 1979, pp. 214-218 .

- ^ Brooks, Grimwood e Swenson, 1979, pp. 265-272 .

- ^ Brooks, Grimwood e Swenson, 1979, pp. 274-284 .

- ^ Brooks, Grimwood e Swenson, 1979, pp. 292-300 .

- ^ Brooks, Grimwood e Swenson, 1979, pp. 303-312 .