Language of flowers – Wikipedia

Cryptological communication through the use or arrangement of flowers

Floriography (language of flowers) is a means of cryptological communication through the use or arrangement of flowers. Meaning has been attributed to flowers for thousands of years, and some form of floriography has been practiced in traditional cultures throughout Europe, Asia, and Africa. Plants and flowers are used as symbols in the Hebrew Bible, particularly of love and lovers in the Song of Songs,[1] as an emblem for the Israelite people,[2] and for the coming Messiah.[3]William Shakespeare ascribed emblematic meanings to flowers, especially in Hamlet.

Interest in floriography soared in Victorian England and in the United States during the 19th century. Gifts of blooms, plants, and specific floral arrangements were used to send a coded message to the recipient, allowing the sender to express feelings which could not be spoken aloud in Victorian society.[4][5] Armed with floral dictionaries, Victorians often exchanged small “talking bouquets”, called nosegays or tussie-mussies, which could be worn or carried as a fashion accessory.[5]: 25, 40–44

History[edit]

According to Jayne Alcock, grounds and gardens supervisor at the Walled Gardens of Cannington, the renewed Victorian era interest in the language of flowers finds its roots in Ottoman Turkey, specifically the court in Constantinople[6] and an obsession it held with tulips during the first half of the 18th century. During the Victorian age, the use of flowers as a means of covert communication conincided with a growing interest in botany. The floriography craze was introduced to Europe by the Englishwoman Mary Wortley Montagu (1689–1762), who brought it to England in 1717, and Aubry de La Mottraye (1674–1743), who introduced it to the Swedish court in 1727. Joseph Hammer-Purgstall’s Dictionnaire du language des fleurs (1809) appears to be the first published list associating flowers with symbolic definitions, while the first dictionary of floriography appears in 1819 when Louise Cortambert, writing under pen name Madame Charlotte de la Tour, wrote Le langage des Fleurs.

Robert Tyas was a popular British flower writer, publisher, and clergyman, who lived from 1811 to 1879; his book, The Sentiment of Flowers; or, Language of Flora, first published in 1836 and reprinted by various publishing houses at least through 1880, was billed as an English version of Charlotte de la Tour’s book.[7]

In the United States the first appearance of the language of flowers in print was in the writings of Constantine Samuel Rafinesque, a French-American naturalist, who wrote on-going features under the title “The School of Flora”, from 1827 through 1828, in the weekly Saturday Evening Post and monthly Casket; or Flowers of Literature, Wit, and Sentiment. These pieces contained the botanic, English and French names of the plant, a description of the plant, an explanation of its Latin names, and the flower’s emblematic meaning. However, the first books on floriography were Elizabeth Wirt’s Flora’s Dictionary and Dorothea Dix’s The Garland of Flora, both of which were published in 1829, though Wirt’s book had been issued in an unauthorized edition in 1828.

During its peak in the United States, the language of flowers attracted the attention of popular writers and editors. Sarah Josepha Hale, longtime editor of the Ladies’ Magazine and co-editor of Godey’s Lady’s Book, edited Flora’s Interpreter in 1832; it continued in print through the 1860s. Catharine H. Waterman Esling wrote a long poem titled “The Language of Flowers”, which first appeared in 1839 in her own language of flowers book, Flora’s Lexicon; it continued in print through the 1860s. Lucy Hooper, an editor, novelist, poet, and playwright, included several of her flower poems in The Lady’s Book of Flowers and Poetry, first published in 1841. Frances Sargent Osgood, a poet and friend of Edgar Allan Poe, first published The Poetry of Flowers and Flowers of Poetry in 1841, and it continued in print through the 1860s.

Meanings[edit]

The significance assigned to specific flowers in Western culture varied – nearly every flower had multiple associations, listed in the hundreds of floral dictionaries – but a consensus of meaning for common blooms has emerged. Often, definitions derive from the appearance or behavior of the plant itself. For example, the mimosa, or sensitive plant, represents chastity. This is because the leaves of the mimosa close at night, or when touched. Likewise, the deep red rose and its thorns have been used to symbolize both the blood of Christ and the intensity of romantic love, while the rose’s five petals are thought to illustrate the five crucifixion wounds of Christ. Pink roses imply a lesser affection, white roses suggest virtue and chastity, and yellow roses stand for friendship or devotion. The black rose (in nature, a very dark shade of red, purple, or maroon, or may be dyed)[8] may be associated with death and darkness due to the traditional (Western) connotations of the shade.[9]

“A woman also had to be pretty precise about where she wore flowers. Say, for instance, a suitor had sent her a tussie-mussie (a.k.a. nosegay). If she pinned it to the ‘cleavage of bosom’, that would be bad news for him, since that signified friendship. Ah, but if she pinned it over her heart, ‘That was an unambiguous declaration of love’.”[10]

Later authors inspired by this tradition created lists that associate a birthday flower with each day of the year.[11]

In literature[edit]

William Shakespeare, Jane Austen, Charlotte and Emily Brontë, and children’s novelist Frances Hodgson Burnett, among others, used the language of flowers in their writings.

I know a bank where the wild thyme blows,

Where oxlips and the nodding violet grows,

Quite over-canopied with luscious woodbine,

With sweet musk-roses and with eglantine:

There sleeps Titania sometime of the night,

Lull’d in these flowers with dances and delight;

– A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Act 2, Scene 1

Shakespeare used the word “flower” more than 100 times in his plays and sonnets.[12] In Hamlet, Ophelia mentions the symbolic meanings of flowers and herbs as she hands them to other characters in Act 4, Scene 5: pansies, rosemary, fennel, lilies, columbine, rue and daisy. She regrets she has no violets, she says, “… but they wither’d all when my father died”.[13] In The Winter’s Tale, the princess Perdita wishes that she had violets, daffodils, and primroses to make garlands for her friends. In A Midsummer Night’s Dream, Oberon talks to his messenger Puck amidst a scene of wild flowers.[14]

In J. K. Rowling’s 1997 novel Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, Professor Severus Snape uses the language of flowers to express regret and mourning for the death of Lily Potter, his childhood friend and Harry Potter’s mother, according to Pottermore.[15]

Flowers are often used as a symbol of femininity. John Steinbeck’s short story “The Chrysanthemums” centers around the yellow florets, which are often associated with optimism and lost love. When the protagonist, Elisa, finds her beloved chrysanthemums tossed on the ground, her hobby and womanhood have been ruined; this suffices the themes of lost appreciation and femininity in Steinbeck’s work.[16]

Several Anglican churches in England have paintings, sculpture, or stained glass windows of the lily crucifix, depicting Christ crucified on or holding a lily. One example is a window at The Clopton Chantry Chapel Church in Long Melford, Suffolk, England, UK.

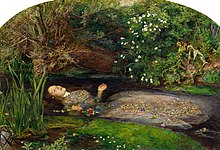

The Victorian Pre-Raphaelites, a group of 19th-century painters and poets who aimed to revive the purer art of the late medieval period, captured classic notions of beauty romantically. These artists are known for their idealistic portrayal of women, emphasis on nature and morality, and use of literature and mythology. Flowers laden with symbolism figure prominently in much of their work. John Everett Millais, a founder of the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood, used oils to create pieces filled with naturalistic elements and rich in floriography. His painting Ophelia (1852) depicts Shakespeare’s drowned stargazer floating amid the flowers she describes in Act IV, Scene V of Hamlet.

The Edwardian artist John Singer Sargent spent much time painting outdoors in the English countryside, frequently utilizing floral symbolism. Sargent’s first major success came in 1887, with Carnation, Lily, Lily, Rose, a large piece painted on site in the plein air manner, of two young girls lighting lanterns in an English garden.

Contemporary artist Whitney Lynn created a site-specific project for the San Diego International Airport[17] employing floriography, utilizing flowers’ ability to communicate messages that otherwise would be restricted or difficult to speak aloud.[18] Lynn previously created a work, Memorial Bouquet,[19] utilizing floral symbolism for the San Francisco Arts Commission Gallery. Based on Dutch Golden Age still-life painting, the flowers in the arrangement represent countries that have been sites of US military operations and conflicts.

See also[edit]

Notes and references[edit]

- ^ Song of Songs 2:1–3

- ^ Psalm 80:10–16

- ^ Isaiah 11:1

- ^ Greenaway, Kate. Language of Flowers. London: George Routledge and Sons.

- ^ a b Laufer, Geraldine Adamich (1993). Tussie-Mussies: The Victorian Art of Expressing Yourself in the Language of Flowers. Workman Publishing. pp. 4–25, 40–53. ISBN 9781563051067.

- ^ “The Language of Flowers”. Bridgwater College. 2016-02-12. Retrieved 2016-03-29.

- ^ Reprints published by Robert Tyas, London, 1841; Houlston and Stoneman, London, 1844; George Routledge and Sons, London, 1869; George Routledge and Sons, London, 1875; George Routledge And Sons, London, 1880.

- ^ “Roses Color Meaning and Symbolism”. www.petalrepublic.com. 2 March 2021. Archived from the original on 8 December 2022. Retrieved 2021-04-20.

- ^ “The Meaning of Black Roses”. Flower Glossary. 11 April 2019.

- ^ Meadow, James B., Rocky Mountain News, 26 January 1998

- ^ Jobes, Gertrude (1962). Dictionary of Mythology, Folklore, and Symbols. New York: The Scarecrow Press.

- ^ “The Language of Flowers”. Folger Shakespeare Library. Archived from the original on 2014-09-19. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

- ^ Eriksson, Katarina. “Ophelia’s Flowers and Their Symbolic Meaning”. Huntington Botanical. Archived from the original on 2020-11-09. Retrieved 2013-05-31.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ “Flowers in Shakespeare’s plays / RHS Campaign for School Gardening”. schoolgardening.rhs.org.uk. Retrieved 2016-11-02.

- ^ “Lily, Petunia and the language of flowers”. Pottermore. Archived from the original on 1 June 2022. Retrieved 2019-04-27.

- ^ “Symbolism in “The Chrysanthemums”“. www.lonestar.edu. Retrieved 2016-10-31.

- ^ “Whitney Lynn”. Arts – SAN. 2018-05-11. Retrieved 2018-09-14.

- ^ “Not Seeing Is A Flower – WHITNEY LYNN”. whitneylynnstudio.com. Retrieved 2018-09-14.

- ^ “Memorial Bouquet – WHITNEY LYNN”. whitneylynnstudio.com. Retrieved 2018-09-14.

- ^ HENG, Michèle (1989), Marc Saint-Saëns décorateur mural et peintre cartonnier de tapisserie, 1964 pages.

Further reading[edit]

Recent Comments