Climate change in Indonesia – Wikipedia

Emissions, impacts and responses of Indonesia related to climate change

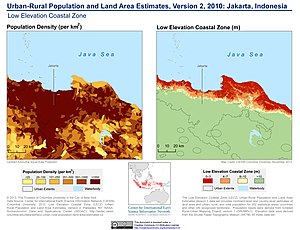

Climate change in Indonesia is of particular significance, because its enormous coastal population is particularly at risk to sea level rise. The livelihoods of many of Indonesians dependent on agriculture, mariculture and fishing could be severely impacted by temperature, rainfall and other climatic changes. Some environmental issues in Indonesia such as the cutting of mangrove forests (i.e. in Java) to make room for fish farms further worsen the effects of climate change (i.e. sea level rise).[1][2]Jakarta has been listed as the world’s most vulnerable city to climate change.[3] In 2019 Indonesia is estimated to have emitted 3.4% of world greenhouse gas emissions:[4] from deforestation, peatland fires, and fossil fuels.[5]

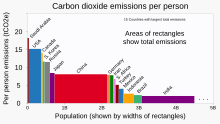

Greenhouse gas emissions[edit]

As of 2021[update] Indonesia is the 5th heaviest cumulative emitter at over 100 Gt.[6] Emissions for 2019 are estimated at 3.4% of the world total.[7] Indonesia has been called the “most ignored emitter” that “could be the one that dooms the global climate.”[8]Coal in Indonesia is a big emitter,[9] because the government subsidizes coal power.[10] As of 2021[update] over 30 coal-fired power plants are planned or under construction,[11] and corruption has been alleged.[10]Perusahaan Listrik Negara, the state electricity company, is in financial difficulties but, as of 2022[update], intends to build more coal-fired power stations.[10]

Impacts on the natural environment[edit]

Temperature and weather changes[edit]

Global climate change is expected to increase temperatures in Indonesia by 0.8 °C by 2030.[12]

Sea level rise and land subsidence[edit]

Difference in sea level rise can differ seasonally during monsoons, where they may average higher in the northwest and lower in the southeast, as well as the variation in tectonic activity in the massive archipelagic state.[13] While the mean sea level rise globally was 3-10mm/year, the subsidence rate for Jakarta was around 75-100mm/year, making the relative rise in sea level nearly 10cm/year.[14] Continued carbon emissions at the 2019 rate, in combination with unlicensed groundwater extraction, is predicted to immerse 95% of Northern Jakarta by 2050.[15]

Some studies have suggested that climate change induced sea level rise may be minimal compared to the rise induced by lack of water infrastructure and rapid urban development.[16] The Indonesian government views land subsidence, mostly due to over extraction of groundwater, as the primary threat to Jakarta’s infrastructure and development.[17] Dutch urban planning is in large part to blame for the water crisis today as a consequence of canals built during the colonial era which intentionally subdivided the city, segregating indigenous people and Europeans, providing clean water access and infrastructure almost exclusively to European settlers.[18][19][20] Due to the lack of access to clean water in Jakarta outside of wealthier communities, many locals have been pushed to extract groundwater without permits.[21] Jakarta’s growing population and rapid urban development has been eating away at the surrounding agriculture further destroying natural flood mitigation, such as forests, and polluting river systems relied on by predominantly poorer locals pushing said locals to rely on groundwater.[22] In 2019, water pipes in Jakarta reached only sixty percent of the population.[21]

Despite this being a very pressing issue in the city, almost half of the local population does not know or have not been made aware of the correlation between land subsidence, their extraction and increased flooding making an organized approach to this issue much more difficult.[23] The issue has persisted so long that Indonesia has confirmed the movement of their nation’s capital, Jakarta, to a new city in East Kalimantan in the island of Borneo, citing the land subsidence issue as a primary reason.[24][25] The movement of the capital to Borneo, in part, minimizes the effects of natural disasters due to its strategic location, but the rapid pace of the planned relocation may exacerbate environmental issues on the island in the near future, particularly biodiversity loss.[26]

Impacts on people[edit]

Economic impacts[edit]

Agriculture[edit]

Changes in rainfall patterns are predicted to have an adverse impact on Indonesian agriculture, due to shorter rainy seasons.[12] Indonesia experienced crop losses and adverse impacts to fisheries as a result of climate change as early as 2007.[27]

Fishery[edit]

By 2020, climate change had impacted Indonesia’s fishermen.[28]

Mitigation and adaptation[edit]

Mitigation approaches[edit]

Coal is expected to provide the majority of Indonesia’s energy through 2025. Indonesia is one of the world’s biggest producers and exporters of coal.[29] In order to keep its commitments to the Paris Agreement, Indonesia must stop building new coal plants, and stop burning coal by 2048.[30]

Indonesia’s first wind farm opened in 2018, the 75MW Sidrap Wind Farm in Sidenreng Rappang Regency, South Sulawesi.[31] Indonesia announced it was unlikely to meet the 23% renewable energy by 2025 target set in the Paris Agreement.[32]

In 2020, “Indonesia will begin integrating the recommendations from its new Low Carbon Development Initiative into its 2020–2024 national development plan.” Mangrove protection and restoration will play an important role in meeting the goal of cutting greenhouse gas emissions by over 43 percent by 2030.[33]

Policies and legislation[edit]

In February 2020, it was announced that the People’s Consultative Assembly is preparing its first renewable energy bill.[29]

Also in February 2020, proposed changes to environmental deregulation have raised new concerns, and could “allow illegal plantations and mines to whitewash their operations.”[34]

Society and culture[edit]

A 2019 survey by YouGov and the University of Cambridge concluded that at 18%, Indonesia has “the biggest percentage of climate deniers, followed by Saudi Arabia (16 percent) and the U.S. (13 percent).”[35]

Climate education is not a part of the school curriculum.[35][36]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Where once were mangroves, Javan villages struggle to beat back the sea

- ^ The importance of mangroves to people Archived 2019-10-12 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ “Climate change: the cities most at risk”. The Week UK. Retrieved 2022-09-09.

- ^ “Report: China emissions exceed all developed nations combined”. BBC News. 2021-05-07.

- ^ “The Carbon Brief Profile: Indonesia”. Carbon Brief. 2019-03-27. Retrieved 2021-05-07.

- ^ “Analysis: Which countries are historically responsible for climate change?”. Carbon Brief. 2021-10-05. Retrieved 2021-10-10.

- ^ “China’s Greenhouse Gas Emissions Exceeded the Developed World for the First Time in 2019”. Rhodium Group. Retrieved 2021-08-25.

- ^ Coca, Nithin (28 March 2018). “The Other Country Crucial to Global Climate Goals: Indonesia”. The Diplomat. Retrieved 5 December 2018.

- ^ Orim, Ruby (2020-12-20). “Indonesia Has Seen a Whopping 313% Increase in Greenhouse Gas Emissions Since 1990”. Climate Scorecard. Retrieved 2021-07-15.

- ^ a b c “Coal Fever in Indonesia”. Earth Journalism Network. 2022-01-13. Retrieved 2022-02-07.

- ^ “South-East Asia”. E3G. Retrieved 2021-09-18.

- ^ a b Oktaviani, Rina; et al. (2011). “The impact of global climate change on the Indonesiannn economy”. IFPRI, International Food Policy Research Institute. Retrieved 2018-12-05.

- ^ Triana, Karlina; Wahyudi, A’an Johan (2020-12-25). “Sea Level Rise in Indonesia: The Drivers and the Combined Impacts from Land Subsidence”. ASEAN Journal on Science and Technology for Development. 37 (3). doi:10.29037/ajstd.627. ISSN 2224-9028. S2CID 234414673.

- ^ Erkens, G.; Bucx, T.; Dam, R.; De Lange, G.; Lambert, J. (2015). “Sinking coastal cities”. ResearchGate. 372: 189–198. Bibcode:2015PIAHS.372..189E. doi:10.5194/piahs-372-189-2015.

- ^ Dickinson, Leta (2019-05-01). “Indonesia might need a new capital because of climate change”. Grist. Retrieved 2019-05-16.

- ^ Abidin, H. Z.; Andreas, H.; Gumilar, I.; Brinkman, J. J. (2015-11-12). “Study on the risk and impacts of land subsidence in Jakarta”. Proceedings of the International Association of Hydrological Sciences. 372: 115–120. Bibcode:2015PIAHS.372..115A. doi:10.5194/piahs-372-115-2015. ISSN 2199-899X.

- ^ Colven, Emma (2020-07-02). “Subterranean infrastructures in a sinking city: the politics of visibility in Jakarta”. Critical Asian Studies. 52 (3): 311–331. doi:10.1080/14672715.2020.1793210. ISSN 1467-2715. S2CID 221299850.

- ^ Kehoe, Marsely L. (January 2015). “Dutch Batavia: Exposing the Hierarchy of the Dutch Colonial City”. Journal of Historians of Netherlandish Art. 7 (1). doi:10.5092/jhna.2015.7.1.3. ISSN 1949-9833.

- ^ Kooy, Michelle; Bakker, Karen (November 2008). “Splintered networks: The colonial and contemporary waters of Jakarta”. Geoforum. 39 (6): 1843–1858. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2008.07.012. ISSN 0016-7185.

- ^ KOOY, MICHELLE; BAKKER, KAREN (June 2008). “Technologies of Government: Constituting Subjectivities, Spaces, and Infrastructures in Colonial and Contemporary Jakarta”. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. 32 (2): 375–391. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2427.2008.00791.x. ISSN 0309-1317.

- ^ a b Horma, Justin. “Phenomenon of Sinking Jakarta from groundwater usage and other drivers that affect its implication Geographically, Social, Economically, and its Environment”. ResearchGate.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: url-status (link) - ^ Douglass, Michael (March 2010). “Globalization, Mega-projects and the Environment”. Environment and Urbanization ASIA. 1 (1): 45–65. doi:10.1177/097542530900100105. ISSN 0975-4253. S2CID 154479761.

- ^ Takagi, Hiroshi; Esteban, Miguel; Mikami, Takahito; Pratama, Munawir Bintang; Valenzuela, Ven Paolo Bruno; Avelino, John Erick (2021-10-01). “People’s perception of land subsidence, floods, and their connection: A note based on recent surveys in a sinking coastal community in Jakarta”. Ocean & Coastal Management. 211: 105753. doi:10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2021.105753. ISSN 0964-5691.

- ^ “Indonesia passes law paving way to move capital to Borneo”. The Japan Times. 2022-01-18. Retrieved 2022-03-23.

- ^ “Why is Indonesia moving its capital city? Everything you need to know”. The Guardian. 2019-08-27. Retrieved 2022-03-12.

- ^ Van de Vuurst, Paige; Escobar, Luis E. (2020-01-30). “Perspective: Climate Change and the Relocation of Indonesia’s Capital to Borneo”. Frontiers in Earth Science. 8: 5. Bibcode:2020FrEaS…8….5V. doi:10.3389/feart.2020.00005. ISSN 2296-6463.

- ^ “Climate Change in Indonesia”. Global Greenhouse Warming. 2018. Retrieved 2018-12-05.

- ^ “Indonesian fishermen grapple with climate change”. The Jakarta Post. January 13, 2020. Archived from the original on 2020-01-13. Retrieved 2020-02-19.

- ^ a b Gokkon, Basten (2020-02-14). “In Indonesian renewables bill, activists see chance to move away from coal”. Mongabay Environmental News. Archived from the original on 2020-02-15. Retrieved 2020-02-19.

- ^ Nugraha, Indra (2019-12-02). “Indonesia ‘must stop building new coal plants by 2020’ to meet climate goals”. Mongabay Environmental News. Archived from the original on 2019-12-02. Retrieved 2020-02-20.

- ^ Andi, Hajramurni (2018-07-02). “Jokowi inaugurates first Indonesian wind farm in Sulawesi”. The Jakarta Post. Archived from the original on 2018-07-05. Retrieved 2020-02-19.

- ^ “Indonesia Struggles to Meet Renewable Energy Target”. Voice of America. November 29, 2018. Archived from the original on 2019-07-19. Retrieved 2020-02-19.

- ^ Barclay, Eliza (2019-12-12). “Supertrees: Meet Indonesia’s mangrove, the tree that stores carbon”. Vox. Retrieved 2020-02-20.

- ^ Jong, Hans Nicholas (2020-02-11). “Experts see minefield of risk as Indonesia seeks environmental deregulation”. Mongabay Environmental News. Archived from the original on 2020-02-12. Retrieved 2020-02-20.

- ^ a b Dickinson, Leta (10 May 2019). “With sea levels rising, why don’t more Indonesians believe in human-caused climate change?”. Grist. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ Putrawidjaja, Mochamad (2008). “Mapping Climate Education in Indonesia”. Jakarta: British Council.

External links[edit]

Recent Comments