Hydrogenation – Wikipedia

Chemical reaction between molecular hydrogen and another compound or element

(1) The reactants are adsorbed on the catalyst surface and H2 dissociates.

(2) An H atom bonds to one C atom. The other C atom is still attached to the surface.

(3) A second C atom bonds to an H atom. The molecule leaves the surface.

| Process type | Chemical |

|---|---|

| Industrial sector(s) | Food industry, petrochemical industry, pharmaceutical industry, agricultural industry |

| Main technologies or sub-processes | Various transition metal catalysts, high-pressure technology |

| Feedstock | Unsaturated substrates and hydrogen or hydrogen donors |

| Product(s) | Saturated hydrocarbons and derivatives |

| Inventor | Paul Sabatier |

| Year of invention | 1897 |

Hydrogenation is a chemical reaction between molecular hydrogen (H2) and another compound or element, usually in the presence of a catalyst such as nickel, palladium or platinum. The process is commonly employed to reduce or saturate organic compounds. Hydrogenation typically constitutes the addition of pairs of hydrogen atoms to a molecule, often an alkene. Catalysts are required for the reaction to be usable; non-catalytic hydrogenation takes place only at very high temperatures. Hydrogenation reduces double and triple bonds in hydrocarbons.[1]

Process[edit]

Hydrogenation has three components, the unsaturated substrate, the hydrogen (or hydrogen source) and, invariably, a catalyst. The reduction reaction is carried out at different temperatures and pressures depending upon the substrate and the activity of the catalyst.

Related or competing reactions[edit]

The same catalysts and conditions that are used for hydrogenation reactions can also lead to isomerization of the alkenes from cis to trans. This process is of great interest because hydrogenation technology generates most of the trans fat in foods. A reaction where bonds are broken while hydrogen is added is called hydrogenolysis, a reaction that may occur to carbon-carbon and carbon-heteroatom (oxygen, nitrogen or halogen) bonds. Some hydrogenations of polar bonds are accompanied by hydrogenolysis.

Hydrogen sources[edit]

For hydrogenation, the obvious source of hydrogen is H2 gas itself, which is typically available commercially within the storage medium of a pressurized cylinder. The hydrogenation process often uses greater than 1 atmosphere of H2, usually conveyed from the cylinders and sometimes augmented by “booster pumps”. Gaseous hydrogen is produced industrially from hydrocarbons by the process known as steam reforming.[2] For many applications, hydrogen is transferred from donor molecules such as formic acid, isopropanol, and dihydroanthracene.[3] These hydrogen donors undergo dehydrogenation to, respectively, carbon dioxide, acetone, and anthracene. These processes are called transfer hydrogenations.

Substrates[edit]

An important characteristic of alkene and alkyne hydrogenations, both the homogeneously and heterogeneously catalyzed versions, is that hydrogen addition occurs with “syn addition”, with hydrogen entering from the least hindered side.[4] This reaction can be performed on a variety of different functional groups.

Catalysts[edit]

With rare exceptions, H2 is unreactive toward organic compounds in the absence of metal catalysts. The unsaturated substrate is chemisorbed onto the catalyst, with most sites covered by the substrate. In heterogeneous catalysts, hydrogen forms surface hydrides (M-H) from which hydrogens can be transferred to the chemisorbed substrate. Platinum, palladium, rhodium, and ruthenium form highly active catalysts, which operate at lower temperatures and lower pressures of H2. Non-precious metal catalysts, especially those based on nickel (such as Raney nickel and Urushibara nickel) have also been developed as economical alternatives, but they are often slower or require higher temperatures. The trade-off is activity (speed of reaction) vs. cost of the catalyst and cost of the apparatus required for use of high pressures. Notice that the Raney-nickel catalysed hydrogenations require high pressures:[8][9]

Catalysts are usually classified into two broad classes: homogeneous and heterogeneous. Homogeneous catalysts dissolve in the solvent that contains the unsaturated substrate. Heterogeneous catalysts are solids that are suspended in the same solvent with the substrate or are treated with gaseous substrate.

Homogeneous catalysts[edit]

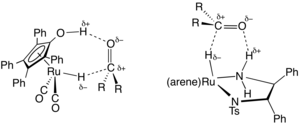

Some well known homogeneous catalysts are indicated below. These are coordination complexes that activate both the unsaturated substrate and the H2. Most typically, these complexes contain platinum group metals, especially Rh and Ir.

Homogeneous catalysts are also used in asymmetric synthesis by the hydrogenation of prochiral substrates. An early demonstration of this approach was the Rh-catalyzed hydrogenation of enamides as precursors to the drug L-DOPA.[10] To achieve asymmetric reduction, these catalyst are made chiral by use of chiral diphosphine ligands.[11] Rhodium catalyzed hydrogenation has also been used in the herbicide production of S-metolachlor, which uses a Josiphos type ligand (called Xyliphos).[12] In principle asymmetric hydrogenation can be catalyzed by chiral heterogeneous catalysts,[13] but this approach remains more of a curiosity than a useful technology.

Heterogeneous catalysts[edit]

Heterogeneous catalysts for hydrogenation are more common industrially. In industry, precious metal hydrogenation catalysts are deposited from solution as a fine powder on the support, which is a cheap, bulky, porous, usually granular material, such as activated carbon, alumina, calcium carbonate or barium sulfate.[14] For example, platinum on carbon is produced by reduction of chloroplatinic acid in situ in carbon. Examples of these catalysts are 5% ruthenium on activated carbon, or 1% platinum on alumina. Base metal catalysts, such as Raney nickel, are typically much cheaper and do not need a support. Also, in the laboratory, unsupported (massive) precious metal catalysts such as platinum black are still used, despite the cost.

As in homogeneous catalysts, the activity is adjusted through changes in the environment around the metal, i.e. the coordination sphere. Different faces of a crystalline heterogeneous catalyst display distinct activities, for example. This can be modified by mixing metals or using different preparation techniques. Similarly, heterogeneous catalysts are affected by their supports.

In many cases, highly empirical modifications involve selective “poisons”. Thus, a carefully chosen catalyst can be used to hydrogenate some functional groups without affecting others, such as the hydrogenation of alkenes without touching aromatic rings, or the selective hydrogenation of alkynes to alkenes using Lindlar’s catalyst. For example, when the catalyst palladium is placed on barium sulfate and then treated with quinoline, the resulting catalyst reduces alkynes only as far as alkenes. The Lindlar catalyst has been applied to the conversion of phenylacetylene to styrene.[15]

Transfer hydrogenation[edit]

Transfer hydrogenation uses hydrogen-donor molecules other than molecular H2. These “sacrificial” hydrogen donors, which can also serve as solvents for the reaction, include hydrazine, formic acid, and alcohols such as isopropanol.[18]

In organic synthesis, transfer hydrogenation is useful for the asymmetric hydrogenation of polar unsaturated substrates, such as ketones, aldehydes and imines, by employing chiral catalysts.

Electrolytic hydrogenation[edit]

Polar substrates such as nitriles can be hydrogenated electrochemically, using protic solvents and reducing equivalents as the source of hydrogen.[19]

Thermodynamics and mechanism[edit]

The addition of hydrogen to double or triple bonds in hydrocarbons is a type of redox reaction that can be thermodynamically favorable. For example, the addition of hydrogen to ethene has a Gibbs free energy change of -101 kJ·mol−1, which is highly exothermic.[11] In the hydrogenation of vegetable oils and fatty acids, for example, the heat released, about 25 kcal per mole (105 kJ/mol), is sufficient to raise the temperature of the oil by 1.6–1.7 °C per iodine number drop.

However, the reaction rate for most hydrogenation reactions is negligible in the absence of catalysts. The mechanism of metal-catalyzed hydrogenation of alkenes and alkynes has been extensively studied.[20] First of all isotope labeling using deuterium confirms the regiochemistry of the addition:

- Heterogeneous catalysis[edit]

On solids, the accepted mechanism is the Horiuti-Polanyi mechanism:[21][22]

- Binding of the unsaturated bond

- Dissociation of H2 on the catalyst

- Addition of one atom of hydrogen; this step is reversible

- Addition of the second atom; effectively irreversible.

In the third step, the alkyl group can revert to alkene, which can detach from the catalyst. Consequently, contact with a hydrogenation catalyst allows cis-trans-isomerization. The trans-alkene can reassociate to the surface and undergo hydrogenation. These details are revealed in part using D2 (deuterium), because recovered alkenes often contain deuterium.

For aromatic substrates, the first hydrogenation is slowest. The product of this step is a cyclohexadiene, which hydrogenate rapidly and are rarely detected. Similarly, the cyclohexene is ordinarily reduced to cyclohexane.

Homogeneous catalysis[edit]

In many homogeneous hydrogenation processes,[23] the metal binds to both components to give an intermediate alkene-metal(H)2 complex. The general sequence of reactions is assumed to be as follows or a related sequence of steps:

- binding of the hydrogen to give a dihydride complex via oxidative addition (preceding the oxidative addition of H2 is the formation of a dihydrogen complex):

- Inorganic substrates[edit]

The hydrogenation of nitrogen to give ammonia is conducted on a vast scale by the Haber–Bosch process, consuming an estimated 1% of the world’s energy supply.

- [24][25]

Industrial applications[edit]

Catalytic hydrogenation has diverse industrial uses. Most frequently, industrial hydrogenation relies on heterogeneous catalysts.[2]

Food industry[edit]

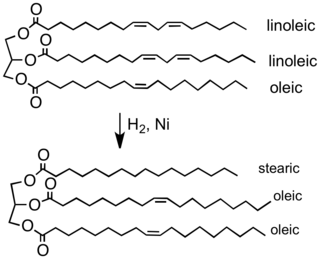

The food industry hydrogenates vegetable oils to convert them into solid or semi-solid fats that can be used in spreads, candies, baked goods, and other products like margarine. Vegetable oils are made from polyunsaturated fatty acids (having more than one carbon-carbon double bond). Hydrogenation eliminates some of these double bonds.[26]

-

Partial hydrogenation of a typical plant oil to a typical component of margarine. Most of the C=C double bonds are removed in this process, which elevates the melting point of the product.

Partial hydrogenation of a typical plant oil to a typical component of margarine. Most of the C=C double bonds are removed in this process, which elevates the melting point of the product.

Petrochemical industry[edit]

In petrochemical processes, hydrogenation is used to convert alkenes and aromatics into saturated alkanes (paraffins) and cycloalkanes (naphthenes), which are less toxic and less reactive. Relevant to liquid fuels that are stored sometimes for long periods in air, saturated hydrocarbons exhibit superior storage properties. On the other hand, alkenes tend to form hydroperoxides, which can form gums that interfere with fuel handling equipment. For example, mineral turpentine is usually hydrogenated. Hydrocracking of heavy residues into diesel is another application. In isomerization and catalytic reforming processes, some hydrogen pressure is maintained to hydrogenolyze coke formed on the catalyst and prevent its accumulation.

Organic chemistry[edit]

Hydrogenation is a useful means for converting unsaturated compounds into saturated derivatives. Substrates include not only alkenes and alkynes, but also aldehydes, imines, and nitriles,[27] which are converted into the corresponding saturated compounds, i.e. alcohols and amines. Thus, alkyl aldehydes, which can be synthesized with the oxo process from carbon monoxide and an alkene, can be converted to alcohols. E.g. 1-propanol is produced from propionaldehyde, produced from ethene and carbon monoxide. Xylitol, a polyol, is produced by hydrogenation of the sugar xylose, an aldehyde. Primary amines can be synthesized by hydrogenation of nitriles, while nitriles are readily synthesized from cyanide and a suitable electrophile. For example, isophorone diamine, a precursor to the polyurethane monomer isophorone diisocyanate, is produced from isophorone nitrile by a tandem nitrile hydrogenation/reductive amination by ammonia, wherein hydrogenation converts both the nitrile into an amine and the imine formed from the aldehyde and ammonia into another amine.

Hydrogenation of coal[edit]

History[edit]

Heterogeneous catalytic hydrogenation[edit]

The earliest hydrogenation was that of the platinum-catalyzed addition of hydrogen to oxygen in the Döbereiner’s lamp, a device commercialized as early as 1823. The French chemist Paul Sabatier is considered the father of the hydrogenation process. In 1897, building on the earlier work of James Boyce, an American chemist working in the manufacture of soap products, he discovered that traces of nickel catalyzed the addition of hydrogen to molecules of gaseous hydrocarbons in what is now known as the Sabatier process. For this work, Sabatier shared the 1912 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Wilhelm Normann was awarded a patent in Germany in 1902 and in Britain in 1903 for the hydrogenation of liquid oils, which was the beginning of what is now a worldwide industry. The commercially important Haber–Bosch process, first described in 1905, involves hydrogenation of nitrogen. In the Fischer–Tropsch process, reported in 1922 carbon monoxide, which is easily derived from coal, is hydrogenated to liquid fuels.

In 1922, Voorhees and Adams described an apparatus for performing hydrogenation under pressures above one atmosphere.[28] The Parr shaker, the first product to allow hydrogenation using elevated pressures and temperatures, was commercialized in 1926 based on Voorhees and Adams’ research and remains in widespread use. In 1924 Murray Raney developed a finely powdered form of nickel, which is widely used to catalyze hydrogenation reactions such as conversion of nitriles to amines or the production of margarine.

Homogeneous catalytic hydrogenation[edit]

In the 1930s, Calvin discovered that copper(II) complexes oxidized H2. The 1960s witnessed the development of well defined homogeneous catalysts using transition metal complexes, e.g., Wilkinson’s catalyst (RhCl(PPh3)3). Soon thereafter cationic Rh and Ir were found to catalyze the hydrogenation of alkenes and carbonyls.[29] In the 1970s, asymmetric hydrogenation was demonstrated in the synthesis of L-DOPA, and the 1990s saw the invention of Noyori asymmetric hydrogenation.[30] The development of homogeneous hydrogenation was influenced by work started in the 1930s and 1940s on the oxo process and Ziegler–Natta polymerization.

Metal-free hydrogenation[edit]

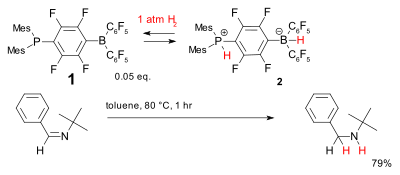

For most practical purposes, hydrogenation requires a metal catalyst. Hydrogenation can, however, proceed from some hydrogen donors without catalysts, illustrative hydrogen donors being diimide and aluminium isopropoxide, the latter illustrated by the Meerwein–Ponndorf–Verley reduction. Some metal-free catalytic systems have been investigated in academic research. One such system for reduction of ketones consists of tert-butanol and potassium tert-butoxide and very high temperatures.[31] The reaction depicted below describes the hydrogenation of benzophenone:

A chemical kinetics study[32] found this reaction is first-order in all three reactants suggesting a cyclic 6-membered transition state.

Another system for metal-free hydrogenation is based on the phosphine-borane, compound 1, which has been called a frustrated Lewis pair. It reversibly accepts dihydrogen at relatively low temperatures to form the phosphonium borate 2 which can reduce simple hindered imines.[33]

The reduction of nitrobenzene to aniline has been reported to be catalysed by fullerene, its mono-anion, atmospheric hydrogen and UV light.[34]

Equipment used for hydrogenation[edit]

Today’s bench chemist has three main choices of hydrogenation equipment:

- Batch hydrogenation under atmospheric conditions

- Batch hydrogenation at elevated temperature and/or pressure[35]

- Flow hydrogenation

Batch hydrogenation under atmospheric conditions[edit]

The original and still a commonly practised form of hydrogenation in teaching laboratories, this process is usually effected by adding solid catalyst to a round bottom flask of dissolved reactant which has been evacuated using nitrogen or argon gas and sealing the mixture with a penetrable rubber seal. Hydrogen gas is then supplied from a H2-filled balloon. The resulting three phase mixture is agitated to promote mixing. Hydrogen uptake can be monitored, which can be useful for monitoring progress of a hydrogenation. This is achieved by either using a graduated tube containing a coloured liquid, usually aqueous copper sulfate or with gauges for each reaction vessel.

Batch hydrogenation at elevated temperature and/or pressure[edit]

Since many hydrogenation reactions such as hydrogenolysis of protecting groups and the reduction of aromatic systems proceed extremely sluggishly at atmospheric temperature and pressure, pressurised systems are popular. In these cases, catalyst is added to a solution of reactant under an inert atmosphere in a pressure vessel. Hydrogen is added directly from a cylinder or built in laboratory hydrogen source, and the pressurized slurry is mechanically rocked to provide agitation, or a spinning basket is used.[35] Recent advances in electrolysis technology have led to the development of high pressure hydrogen generators, which generate hydrogen up to 1,400 psi (100 bar) from water. Heat may also be used, as the pressure compensates for the associated reduction in gas solubility.

Flow hydrogenation[edit]

Flow hydrogenation has become a popular technique at the bench and increasingly the process scale. This technique involves continuously flowing a dilute stream of dissolved reactant over a fixed bed catalyst in the presence of hydrogen. Using established high-performance liquid chromatography technology, this technique allows the application of pressures from atmospheric to 1,450 psi (100 bar). Elevated temperatures may also be used. At the bench scale, systems use a range of pre-packed catalysts which eliminates the need for weighing and filtering pyrophoric catalysts.

Industrial reactors[edit]

Catalytic hydrogenation is done in a tubular plug-flow reactor packed with a supported catalyst. The pressures and temperatures are typically high, although this depends on the catalyst. Catalyst loading is typically much lower than in laboratory batch hydrogenation, and various promoters are added to the metal, or mixed metals are used, to improve activity, selectivity and catalyst stability. The use of nickel is common despite its low activity, due to its low cost compared to precious metals.

Gas liquid induction reactors (hydrogenator) are also used for carrying out catalytic hydrogenation.[36]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Hudlický, Miloš (1996). Reductions in Organic Chemistry. Washington, D.C.: American Chemical Society. p. 429. ISBN 978-0-8412-3344-7.

- ^ a b Paul N. Rylander, “Hydrogenation and Dehydrogenation” in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2005. doi:10.1002/14356007.a13_487

- ^ Beck, Shay. Organometallic Chemistry. United Kingdom, EDTECH, 2019.

- ^ Advanced Organic Chemistry Jerry March 2nd Edition[full citation needed]

- ^ Scott D. Barnicki “Synthetic Organic Chemicals” in Handbook of Industrial Chemistry and Biotechnology edited by James A. Kent, New York : Springer, 2012. 12th ed. ISBN 978-1-4614-4259-2.

- ^ “Hydrogenation of nitrobenzene using polymer bound Ru(III) complexes as catalyst”. Ind. Jr. Of Chem. Tech. 7: 280. 2000.

- ^ Patel, D. R. (1998). “Hydrogenation of nitrobenzene using polymer anchored Pd(II) complexes as catalyst”. Journal of Molecular Catalysis. 130 (1–2): 57. doi:10.1016/s1381-1169(97)00197-0.

- ^ C. F. H. Allen and James VanAllan (1955). “m-Toylybenzylamine”. Organic Syntheses.; Collective Volume, vol. 3, p. 827

- ^ A. B. Mekler, S. Ramachandran, S. Swaminathan, and Melvin S. Newman (1973). “2-Methyl-1,3-Cyclohexanedione”. Organic Syntheses.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link); Collective Volume, vol. 5, p. 743 - ^ Knowles, W. S. (March 1986). “Application of organometallic catalysis to the commercial production of L-DOPA”. Journal of Chemical Education. 63 (3): 222. Bibcode:1986JChEd..63..222K. doi:10.1021/ed063p222.

- ^ a b Atkins, Peter W. (2010). Shriver & Atkins’ inorganic chemistry (5th ed.). New York: W. H. Freeman and Co. p. 696. ISBN 978-1-4292-1820-7.

- ^ Blaser, Hans-Ulrich; Pugin, Benoît; Spindler, Felix; Thommen, Marc (December 2007). “From a Chiral Switch to a Ligand Portfolio for Asymmetric Catalysis”. Accounts of Chemical Research. 40 (12): 1240–1250. doi:10.1021/ar7001057. PMID 17715990.

- ^ Mallat, T.; Orglmeister, E.; Baiker, A. (2007). “Asymmetric Catalysis at Chiral Metal Surfaces”. Chemical Reviews. 107 (11): 4863–90. doi:10.1021/cr0683663. PMID 17927256.

- ^ “Platinum Heterogeneous Catalysts – Alfa Aesar”. www.alfa.com. Archived from the original on 18 January 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2018.

- ^ H. Lindlar and R. Dubuis (1973). “Palladium Catalyst for Partial Reduction of Acetylenes”. Organic Syntheses.; Collective Volume, vol. 5, p. 880

- ^ S. Robert E. Ireland and P. Bey (1988). “Homogeneous Catalytic Hydrogenation: Dihydrocarvone”. Organic Syntheses.; Collective Volume, vol. 6, p. 459

- ^ Amoa, Kwesi (2007). “Catalytic Hydrogenation of Maleic Acid at Moderate Pressures A Laboratory Demonstration”. Journal of Chemical Education. 84 (12): 1948. Bibcode:2007JChEd..84.1948A. doi:10.1021/ed084p1948.

- ^ Wang, Dong; Astruc, Didier (2015). “The Golden Age of Transfer Hydrogenation”. Chem. Rev. 115 (13): 6621–6686. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00203. ISSN 0009-2665. PMID 26061159.

- ^ Navarro, Daniela Maria do Amaral Ferraz; Navarro, Marcelo (2004). “Catalytic Hydrogenation of Organic Compounds without H2 Supply: An Electrochemical System”. Journal of Chemical Education. 81 (9): 1350. Bibcode:2004JChEd..81.1350N. doi:10.1021/ed081p1350. S2CID 93416392.

- ^ Kubas, G. J., “Metal Dihydrogen and σ-Bond Complexes”, Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers: New York, 2001

- ^ Gallezot, Pierre. “Hydrogenation – Heterogeneous” in Encyclopedia of Catalysis, Volume 4, ed. Horvath, I.T., John Wiley & Sons, 2003.

- ^ Horiuti, Iurô; Polanyi, M. (1934). “Exchange reactions of hydrogen on metallic catalysts”. Transactions of the Faraday Society. 30: 1164. doi:10.1039/TF9343001164.

- ^ Johannes G. de Vries, Cornelis J. Elsevier, eds. The Handbook of Homogeneous Hydrogenation Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2007. ISBN 978-3-527-31161-3

- ^ Noritaka Mizuno Gabriele Centi, Siglinda Perathoner, Salvatore Abate “Direct Synthesis of Hydrogen Peroxide: Recent Advances” in Modern Heterogeneous Oxidation Catalysis: Design, Reactions and Characterization 2009, Wiley-VCH. doi:10.1002/9783527627547.ch8

- ^ Edwards, Jennifer K.; Solsona, Benjamin; N, Edwin Ntainjua; Carley, Albert F.; Herzing, Andrew A.; Kiely, Christopher J.; Hutchings, Graham J. (20 February 2009). “Switching Off Hydrogen Peroxide Hydrogenation in the Direct Synthesis Process”. Science. 323 (5917): 1037–1041. Bibcode:2009Sci…323.1037E. doi:10.1126/science.1168980. PMID 19229032. S2CID 1828874.

- ^ Ian P. Freeman “Margarines and Shortenings” in Ullmann’s Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry, 2005, Wiley-VCH, Weinheim. doi:10.1002/14356007.a16_145

- ^ Werkmeister, Svenja; Junge, Kathrin; Beller, Matthias (2 February 2014). “Catalytic Hydrogenation of Carboxylic Acid Esters, Amides, and Nitriles with Homogeneous Catalysts”. Organic Process Research & Development. 18 (2): 289–302. doi:10.1021/op4003278.

- ^ “Archived copy” (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2008-09-10. Retrieved 2008-08-05.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ Schrock, Richard R.; Osborn, John A. (April 1976). “Catalytic hydrogenation using cationic rhodium complexes. I. Evolution of the catalytic system and the hydrogenation of olefins”. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 98 (8): 2134–2143. doi:10.1021/ja00424a020.

- ^ C. Pettinari, F. Marchetti, D. Martini “Metal Complexes as Hydrogenation Catalysts” Comprehensive Coordination Chemistry II, 2004, volume 9. pp. 75–139. doi:10.1016/B0-08-043748-6/09125-8

- ^ Walling, Cheves.; Bollyky, Laszlo. (1964). “Homogeneous Hydrogenation in the Absence of Transition-Metal Catalysts”. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 86 (18): 3750. doi:10.1021/ja01072a028.

- ^ Berkessel, Albrecht; Schubert, Thomas J. S.; Müller, Thomas N. (2002). “Hydrogenation without a Transition-Metal Catalyst: On the Mechanism of the Base-Catalyzed Hydrogenation of Ketones”. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 124 (29): 8693–8. doi:10.1021/ja016152r. PMID 12121113.

- ^ Chase, Preston A.; Welch, Gregory C.; Jurca, Titel; Stephan, Douglas W. (2007). “Metal-Free Catalytic Hydrogenation”. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 46 (42): 8050–3. doi:10.1002/anie.200702908. PMID 17696181.

- ^ Li, Baojun; Xu, Zheng (2009). “A Nonmetal Catalyst for Molecular Hydrogen Activation with Comparable Catalytic Hydrogenation Capability to Noble Metal Catalyst”. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 131 (45): 16380–2. doi:10.1021/ja9061097. PMID 19845383.

- ^ a b Adams, Roger; Voorhees, V. (1928). “Apparatus for catalytic reduction”. Organic Syntheses. 8: 10. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.008.0010.

- ^ Joshi, J.B.; Pandit, A.B.; Sharma, M.M. (1982). “Mechanically agitated gas–liquid reactors”. Chemical Engineering Science. 37 (6): 813. doi:10.1016/0009-2509(82)80171-1.

Further reading[edit]

- Jang ES, Jung MY, Min DB (2005). “Hydrogenation for Low Trans and High Conjugated Fatty Acids” (PDF). Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 1. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-17.

- examples of hydrogenation from Organic Syntheses:

- early work on transfer hydrogenation:

External links[edit]

-

- [24][25]

- Inorganic substrates[edit]

![Hydrogenation of nitrogen {displaystyle {ce {{underset {nitrogen}{N{equiv }N}}+{underset {hydrogen atop (200atm)}{3H2}}->[{ce {Fe catalyst}}][350-550^{circ }{ce {C}}]{underset {ammonia}{2NH3}}}}}”/></span></dd>

</dl>

<p>Oxygen can be partially hydrogenated to give hydrogen peroxide, although this process has not been commercialized. One difficulty is preventing the catalysts from triggering decomposition of the hydrogen peroxide to form water.<sup id=](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/2dd5645111a3ad991987a7b9e10599029c287e98) [24][25]

[24][25]

Recent Comments