Sphere – Wikipedia

Geometrical object that is the surface of a ball

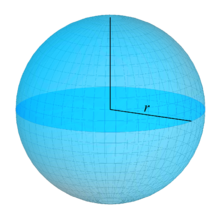

A sphere (from Ancient Greek σφαῖρα (sphaîra) ‘globe, ball’)[1] is a geometrical object that is a three-dimensional analogue to a two-dimensional circle. A sphere is the set of points that are all at the same distance r from a given point in three-dimensional space.[2] That given point is the centre of the sphere, and r is the sphere’s radius. The earliest known mentions of spheres appear in the work of the ancient Greek mathematicians.

The sphere is a fundamental object in many fields of mathematics. Spheres and nearly-spherical shapes also appear in nature and industry. Bubbles such as soap bubbles take a spherical shape in equilibrium. The Earth is often approximated as a sphere in geography, and the celestial sphere is an important concept in astronomy. Manufactured items including pressure vessels and most curved mirrors and lenses are based on spheres. Spheres roll smoothly in any direction, so most balls used in sports and toys are spherical, as are ball bearings.

Basic terminology[edit]

As mentioned earlier r is the sphere’s radius; any line from the center to a point on the sphere is also called a radius.[3]

If a radius is extended through the center to the opposite side of the sphere, it creates a diameter. Like the radius, the length of a diameter is also called the diameter, and denoted d. Diameters are the longest line segments that can be drawn between two points on the sphere: their length is twice the radius, d = 2r. Two points on the sphere connected by a diameter are antipodal points of each other.[3]

A unit sphere is a sphere with unit radius (r = 1). For convenience, spheres are often taken to have their center at the origin of the coordinate system, and spheres in this article have their center at the origin unless a center is mentioned.

A great circle on the sphere has the same center and radius as the sphere, and divides it into two equal hemispheres.

Although the Earth is not perfectly spherical, terms borrowed from geography are convenient to apply to the sphere.

If a particular point on a sphere is (arbitrarily) designated as its north pole, its antipodal point is called the south pole. The great circle equidistant to each is then the equator. Great circles through the poles are called lines of longitude or meridians. A line connecting the two poles may be called the axis of rotation. Small circles on the sphere that are parallel to the equator are lines of latitude. In geometry unrelated to astronomical bodies, geocentric terminology should be used only for illustration and noted as such, unless there is no chance of misunderstanding.[3]

Mathematicians consider a sphere to be a two-dimensional closed surface embedded in three-dimensional Euclidean space. They draw a distinction a sphere and a ball, which is a three-dimensional manifold with boundary that includes the volume contained by the sphere. An open ball excludes the sphere itself, while a closed ball includes the sphere: a closed ball is the union of the open ball and the sphere, and a sphere is the boundary of a (closed or open) ball. The distinction between ball and sphere has not always been maintained and especially older mathematical references talk about a sphere as a solid. The distinction between “circle” and “disk” in the plane is similar.

Small spheres or balls are sometimes called spherules, e.g. in Martian spherules.

Equations[edit]

In analytic geometry, a sphere with center (x0, y0, z0) and radius r is the locus of all points (x, y, z) such that

Since it can be expressed as a quadratic polynomial, a sphere is a quadric surface, a type of algebraic surface.[3]

Let a, b, c, d, e be real numbers with a ≠ 0 and put

Then the equation

has no real points as solutions if

and is called the equation of an imaginary sphere. If

, the only solution of

is the point

and the equation is said to be the equation of a point sphere. Finally, in the case

is an equation of a sphere whose center is

and whose radius is

.[2]

If a in the above equation is zero then f(x, y, z) = 0 is the equation of a plane. Thus, a plane may be thought of as a sphere of infinite radius whose center is a point at infinity.[4]

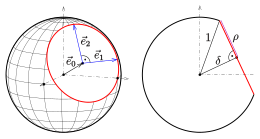

Parametric[edit]

A parametric equation for the sphere with radius

can be parameterized using trigonometric functions.

- [5]

The symbols used here are the same as those used in spherical coordinates. r is constant, while θ varies from 0 to π and

varies from 0 to 2π.

Properties[edit]

Enclosed volume[edit]

In three dimensions, the volume inside a sphere (that is, the volume of a ball, but classically referred to as the volume of a sphere) is

where r is the radius and d is the diameter of the sphere. Archimedes first derived this formula by showing that the volume inside a sphere is twice the volume between the sphere and the circumscribed cylinder of that sphere (having the height and diameter equal to the diameter of the sphere).[6] This may be proved by inscribing a cone upside down into semi-sphere, noting that the area of a cross section of the cone plus the area of a cross section of the sphere is the same as the area of the cross section of the circumscribing cylinder, and applying Cavalieri’s principle.[7] This formula can also be derived using integral calculus, i.e. disk integration to sum the volumes of an infinite number of circular disks of infinitesimally small thickness stacked side by side and centered along the x-axis from x = −r to x = r, assuming the sphere of radius r is centered at the origin.

|

Proof of sphere volume, using calculus |

|---|

|

At any given x, the incremental volume (δV) equals the product of the cross-sectional area of the disk at x and its thickness (δx): The total volume is the summation of all incremental volumes: In the limit as δx approaches zero,[8] this equation becomes: At any given x, a right-angled triangle connects x, y and r to the origin; hence, applying the Pythagorean theorem yields: Using this substitution gives which can be evaluated to give the result An alternative formula is found using spherical coordinates, with volume element so |

For most practical purposes, the volume inside a sphere inscribed in a cube can be approximated as 52.4% of the volume of the cube, since V = π/6 d3, where d is the diameter of the sphere and also the length of a side of the cube and π/6 ≈ 0.5236. For example, a sphere with diameter 1 m has 52.4% the volume of a cube with edge length 1 m, or about 0.524 m3.

Surface area[edit]

The surface area of a sphere of radius r is:

Archimedes first derived this formula[9] from the fact that the projection to the lateral surface of a circumscribed cylinder is area-preserving.[10] Another approach to obtaining the formula comes from the fact that it equals the derivative of the formula for the volume with respect to r because the total volume inside a sphere of radius r can be thought of as the summation of the surface area of an infinite number of spherical shells of infinitesimal thickness concentrically stacked inside one another from radius 0 to radius r. At infinitesimal thickness the discrepancy between the inner and outer surface area of any given shell is infinitesimal, and the elemental volume at radius r is simply the product of the surface area at radius r and the infinitesimal thickness.

|

Proof of surface area, using calculus |

|---|

|

At any given radius r,[note 1] the incremental volume (δV) equals the product of the surface area at radius r (A(r)) and the thickness of a shell (δr): The total volume is the summation of all shell volumes: In the limit as δr approaches zero[8] this equation becomes: Substitute V: Differentiating both sides of this equation with respect to r yields A as a function of r: This is generally abbreviated as: where r is now considered to be the fixed radius of the sphere. Alternatively, the area element on the sphere is given in spherical coordinates by dA = r2 sin θ dθ dφ. In Cartesian coordinates, the area element is[citation needed] The total area can thus be obtained by integration: |

The sphere has the smallest surface area of all surfaces that enclose a given volume, and it encloses the largest volume among all closed surfaces with a given surface area.[11] The sphere therefore appears in nature: for example, bubbles and small water drops are roughly spherical because the surface tension locally minimizes surface area.

The surface area relative to the mass of a ball is called the specific surface area and can be expressed from the above stated equations as

where ρ is the density (the ratio of mass to volume).

Other geometric properties[edit]

A sphere can be constructed as the surface formed by rotating a circle about any of its diameters; this is essentially the traditional definition of a sphere as given in Euclid’s Elements. Since a circle is a special type of ellipse, a sphere is a special type of ellipsoid of revolution. Replacing the circle with an ellipse rotated about its major axis, the shape becomes a prolate spheroid; rotated about the minor axis, an oblate spheroid.[12]

A sphere is uniquely determined by four points that are not coplanar. More generally, a sphere is uniquely determined by four conditions such as passing through a point, being tangent to a plane, etc.[13] This property is analogous to the property that three non-collinear points determine a unique circle in a plane.

Consequently, a sphere is uniquely determined by (that is, passes through) a circle and a point not in the plane of that circle.

By examining the common solutions of the equations of two spheres, it can be seen that two spheres intersect in a circle and the plane containing that circle is called the radical plane of the intersecting spheres.[14] Although the radical plane is a real plane, the circle may be imaginary (the spheres have no real point in common) or consist of a single point (the spheres are tangent at that point).[15]

The angle between two spheres at a real point of intersection is the dihedral angle determined by the tangent planes to the spheres at that point. Two spheres intersect at the same angle at all points of their circle of intersection.[16] They intersect at right angles (are orthogonal) if and only if the square of the distance between their centers is equal to the sum of the squares of their radii.[4]

Pencil of spheres[edit]

If f(x, y, z) = 0 and g(x, y, z) = 0 are the equations of two distinct spheres then

is also the equation of a sphere for arbitrary values of the parameters s and t. The set of all spheres satisfying this equation is called a pencil of spheres determined by the original two spheres. In this definition a sphere is allowed to be a plane (infinite radius, center at infinity) and if both the original spheres are planes then all the spheres of the pencil are planes, otherwise there is only one plane (the radical plane) in the pencil.[4]

Properties of the sphere[edit]

In their book Geometry and the Imagination, David Hilbert and Stephan Cohn-Vossen describe eleven properties of the sphere and discuss whether these properties uniquely determine the sphere.[17] Several properties hold for the plane, which can be thought of as a sphere with infinite radius. These properties are:

- The points on the sphere are all the same distance from a fixed point. Also, the ratio of the distance of its points from two fixed points is constant.

- The first part is the usual definition of the sphere and determines it uniquely. The second part can be easily deduced and follows a similar result of Apollonius of Perga for the circle. This second part also holds for the plane.

- The contours and plane sections of the sphere are circles.

- This property defines the sphere uniquely.

- The sphere has constant width and constant girth.

- The width of a surface is the distance between pairs of parallel tangent planes. Numerous other closed convex surfaces have constant width, for example the Meissner body. The girth of a surface is the circumference of the boundary of its orthogonal projection on to a plane. Each of these properties implies the other.

- All points of a sphere are umbilics.

- At any point on a surface a normal direction is at right angles to the surface because on the sphere these are the lines radiating out from the center of the sphere. The intersection of a plane that contains the normal with the surface will form a curve that is called a normal section, and the curvature of this curve is the normal curvature. For most points on most surfaces, different sections will have different curvatures; the maximum and minimum values of these are called the principal curvatures. Any closed surface will have at least four points called umbilical points. At an umbilic all the sectional curvatures are equal; in particular the principal curvatures are equal. Umbilical points can be thought of as the points where the surface is closely approximated by a sphere.

- For the sphere the curvatures of all normal sections are equal, so every point is an umbilic. The sphere and plane are the only surfaces with this property.

- The sphere does not have a surface of centers.

- For a given normal section exists a circle of curvature that equals the sectional curvature, is tangent to the surface, and the center lines of which lie along on the normal line. For example, the two centers corresponding to the maximum and minimum sectional curvatures are called the focal points, and the set of all such centers forms the focal surface.

- For most surfaces the focal surface forms two sheets that are each a surface and meet at umbilical points. Several cases are special:

- * For channel surfaces one sheet forms a curve and the other sheet is a surface

- * For cones, cylinders, tori and cyclides both sheets form curves.

- * For the sphere the center of every osculating circle is at the center of the sphere and the focal surface forms a single point. This property is unique to the sphere.

- All geodesics of the sphere are closed curves.

- Geodesics are curves on a surface that give the shortest distance between two points. They are a generalization of the concept of a straight line in the plane. For the sphere the geodesics are great circles. Many other surfaces share this property.

- Of all the solids having a given volume, the sphere is the one with the smallest surface area; of all solids having a given surface area, the sphere is the one having the greatest volume.

- It follows from isoperimetric inequality. These properties define the sphere uniquely and can be seen in soap bubbles: a soap bubble will enclose a fixed volume, and surface tension minimizes its surface area for that volume. A freely floating soap bubble therefore approximates a sphere (though such external forces as gravity will slightly distort the bubble’s shape). It can also be seen in planets and stars where gravity minimizes surface area for large celestial bodies.

- The sphere has the smallest total mean curvature among all convex solids with a given surface area.

- The mean curvature is the average of the two principal curvatures, which is constant because the two principal curvatures are constant at all points of the sphere.

- The sphere has constant mean curvature.

- The sphere is the only imbedded surface that lacks boundary or singularities with constant positive mean curvature. Other such immersed surfaces as minimal surfaces have constant mean curvature.

- The sphere has constant positive Gaussian curvature.

- Gaussian curvature is the product of the two principal curvatures. It is an intrinsic property that can be determined by measuring length and angles and is independent of how the surface is embedded in space. Hence, bending a surface will not alter the Gaussian curvature, and other surfaces with constant positive Gaussian curvature can be obtained by cutting a small slit in the sphere and bending it. All these other surfaces would have boundaries, and the sphere is the only surface that lacks a boundary with constant, positive Gaussian curvature. The pseudosphere is an example of a surface with constant negative Gaussian curvature.

- The sphere is transformed into itself by a three-parameter family of rigid motions.

- Rotating around any axis a unit sphere at the origin will map the sphere onto itself. Any rotation about a line through the origin can be expressed as a combination of rotations around the three-coordinate axis (see Euler angles). Therefore, a three-parameter family of rotations exists such that each rotation transforms the sphere onto itself; this family is the rotation group SO(3). The plane is the only other surface with a three-parameter family of transformations (translations along the x– and y-axes and rotations around the origin). Circular cylinders are the only surfaces with two-parameter families of rigid motions and the surfaces of revolution and helicoids are the only surfaces with a one-parameter family.

Treatment by area of mathematics[edit]

Spherical geometry[edit]

The basic elements of Euclidean plane geometry are points and lines. On the sphere, points are defined in the usual sense. The analogue of the “line” is the geodesic, which is a great circle; the defining characteristic of a great circle is that the plane containing all its points also passes through the center of the sphere. Measuring by arc length shows that the shortest path between two points lying on the sphere is the shorter segment of the great circle that includes the points.

Many theorems from classical geometry hold true for spherical geometry as well, but not all do because the sphere fails to satisfy some of classical geometry’s postulates, including the parallel postulate. In spherical trigonometry, angles are defined between great circles. Spherical trigonometry differs from ordinary trigonometry in many respects. For example, the sum of the interior angles of a spherical triangle always exceeds 180 degrees. Also, any two similar spherical triangles are congruent.

Any pair of points on a sphere that lie on a straight line through the sphere’s center (i.e. the diameter) are called antipodal points—on the sphere, the distance between them is exactly half the length of the circumference.[note 2] Any other (i.e. not antipodal) pair of distinct points on a sphere

- lie on a unique great circle,

- segment it into one minor (i.e. shorter) and one major (i.e. longer) arc, and

- have the minor arc’s length be the shortest distance between them on the sphere.[note 3]

Spherical geometry is a form of elliptic geometry, which together with hyperbolic geometry makes up non-Euclidean geometry.

Differential geometry[edit]

The sphere is a smooth surface with constant Gaussian curvature at each point equal to 1/r2.[9] As per Gauss’s Theorema Egregium, this curvature is independent of the sphere’s embedding in 3-dimensional space. Also following from Gauss, a sphere cannot be mapped to a plane while maintaining both areas and angles. Therefore, any map projection introduces some form of distortion.

A sphere of radius r has area element

. This can be found from the volume element in spherical coordinates with r held constant.[9]

A sphere of any radius centered at zero is an integral surface of the following differential form:

This equation reflects that the position vector and tangent plane at a point are always orthogonal to each other. Furthermore, the outward-facing normal vector is equal to the position vector scaled by 1/r.

In Riemannian geometry, the filling area conjecture states that the hemisphere is the optimal (least area) isometric filling of the Riemannian circle.

Topology[edit]

Remarkably, it is possible to turn an ordinary sphere inside out in a three-dimensional space with possible self-intersections but without creating any creases, in a process called sphere eversion.

The antipodal quotient of the sphere is the surface called the real projective plane, which can also be thought of as the Northern Hemisphere with antipodal points of the equator identified.

Curves on a sphere [edit]

Circles[edit]

Circles on the sphere are, like circles in the plane, made up of all points a certain distance from a fixed point on the sphere. The intersection of a sphere and a plane is a circle, a point, or empty.[18] Great circles are the intersection of the sphere with a plane passing through the center of a sphere: others are called small circles.

More complicated surfaces may intersect a sphere in circles, too: the intersection of a sphere with a surface of revolution whose axis contains the center of the sphere (are coaxial) consists of circles and/or points if not empty. For example, the diagram to the right shows the intersection of a sphere and a cylinder, which consists of two circles. If the cylinder radius were that of the sphere, the intersection would be a single circle. If the cylinder radius were larger than that of the sphere, the intersection would be empty.

Loxodrome[edit]

In navigation, a rhumb line or loxodrome is an arc crossing all meridians of longitude at the same angle. Loxodromes are the same as straight lines in the Mercator projection. A rhumb line is not a spherical spiral. Except for some simple cases, the formula of a rhumb line is complicated.

Clelia curves[edit]

A Clelia curve is a curve on a sphere for which the longitude

and the colatitude

satisfy the equation

- ) and spherical spirals (Spherical conics[edit]

The analog of a conic section on the sphere is a spherical conic, a quartic curve which can be defined in several equivalent ways, including:

- as the intersection of a sphere with a quadratic cone whose vertex is the sphere center;

- as the intersection of a sphere with an elliptic or hyperbolic cylinder whose axis passes through the sphere center;

- as the locus of points whose sum or difference of great-circle distances from a pair of foci is a constant.

Many theorems relating to planar conic sections also extend to spherical conics.

Intersection of a sphere with a more general surface[edit]

General intersection sphere-cylinder

General intersection sphere-cylinderIf a sphere is intersected by another surface, there may be more complicated spherical curves.

- Example

- sphere – cylinder

The intersection of the sphere with equation

and the cylinder with equation

is not just one or two circles. It is the solution of the non-linear system of equations

(see implicit curve and the diagram)

Generalizations[edit]

Ellipsoids[edit]

An ellipsoid is a sphere that has been stretched or compressed in one or more directions. More exactly, it is the image of a sphere under an affine transformation. An ellipsoid bears the same relationship to the sphere that an ellipse does to a circle.

Dimensionality[edit]

Spheres can be generalized to spaces of any number of dimensions. For any natural number n, an n-sphere, often denoted Sn, is the set of points in (n + 1)-dimensional Euclidean space that are at a fixed distance r from a central point of that space, where r is, as before, a positive real number. In particular:

- S0: a 0-sphere consists of two discrete points, −r and r

- S1: a 1-sphere is a circle of radius r

- S2: a 2-sphere is an ordinary sphere

- S3: a 3-sphere is a sphere in 4-dimensional Euclidean space.

Spheres for n > 2 are sometimes called hyperspheres.

The n-sphere of unit radius centered at the origin is denoted Sn and is often referred to as “the” n-sphere. The ordinary sphere is a 2-sphere, because it is a 2-dimensional surface which is embedded in 3-dimensional space.

In topology, the n-sphere is an example of a compact topological manifold without boundary. A topological sphere need not be smooth; if it is smooth, it need not be diffeomorphic to the Euclidean sphere (an exotic sphere).

The sphere is the inverse image of a one-point set under the continuous function ||x||, so it is closed; Sn is also bounded, so it is compact by the Heine–Borel theorem.

Metric spaces[edit]

More generally, in a metric space (E,d), the sphere of center x and radius r > 0 is the set of points y such that d(x,y) = r.

If the center is a distinguished point that is considered to be the origin of E, as in a normed space, it is not mentioned in the definition and notation. The same applies for the radius if it is taken to equal one, as in the case of a unit sphere.

Unlike a ball, even a large sphere may be an empty set. For example, in Zn with Euclidean metric, a sphere of radius r is nonempty only if r2 can be written as sum of n squares of integers.

An octahedron is a sphere in taxicab geometry, and a cube is a sphere in geometry using the Chebyshev distance.

History[edit]

The geometry of the sphere was studied by the Greeks. Euclid’s Elements defines the sphere in book XI, discusses various properties of the sphere in book XII, and shows how to inscribe the five regular polyhedra within a sphere in book XIII. Euclid does not include the area and volume of a sphere, only a theorem that the volume of a sphere varies as the third power of its diameter, probably due to Eudoxus of Cnidus. The volume and area formulas were first determined in Archimedes’s On the Sphere and Cylinder by the method of exhaustion. Zenodorus was the first to state that, for a given surface area, the sphere is the solid of maximum volume.[3]

Archimedes wrote about the problem of dividing a sphere into segments whose volumes are in a given ratio, but did not solve it. A solution by means of the parabola and hyperbola was given by Dionysodorus.[19] A similar problem — to construct a segment equal in volume to a given segment, and in surface to another segment — was solved later by al-Quhi.[3]

Gallery[edit]

-

Deck of playing cards illustrating engineering instruments, England, 1702. King of spades: Spheres

Regions[edit]

See also[edit]

Notes and references[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ r is being considered as a variable in this computation.

- ^ It does not matter which direction is chosen, the distance is the sphere’s radius × π.

- ^ The distance between two non-distinct points (i.e. a point and itself) on the sphere is zero.

References[edit]

- ^ σφαῖρα, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus.

- ^ a b Albert 2016, p. 54.

- ^ a b c d e f Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 647–648.

- ^ a b c Woods 1961, p. 266.

- ^ Kreyszig (1972, p. 342).

- ^ Steinhaus 1969, p. 223.

- ^ “The volume of a sphere – Math Central”. mathcentral.uregina.ca. Retrieved 10 June 2019.

- ^ a b E.J. Borowski; J.M. Borwein (1989). Collins Dictionary of Mathematics. pp. 141, 149. ISBN 978-0-00-434347-1.

- ^ a b c Weisstein, Eric W. “Sphere”. MathWorld.

- ^ Steinhaus 1969, p. 221.

- ^ Osserman, Robert (1978). “The isoperimetric inequality”. Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society. 84 (6): 1187. doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1978-14553-4. Retrieved 14 December 2019.

- ^ Albert 2016, p. 60.

- ^ Albert 2016, p. 55.

- ^ Albert 2016, p. 57.

- ^ Woods 1961, p. 267.

- ^ Albert 2016, p. 58.

- ^ Hilbert, David; Cohn-Vossen, Stephan (1952). “Eleven properties of the sphere”. Geometry and the Imagination (2nd ed.). Chelsea. pp. 215–231. ISBN 978-0-8284-1087-8.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W. “Spheric section”. MathWorld.

- ^ Fried, Michael N. (25 February 2019). “conic sections”. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Classics. doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780199381135.013.8161. ISBN 978-0-19-938113-5. Retrieved 4 November 2022.

More significantly, Vitruvius (On Architecture, Vitr. 9.8) associated conical sundials with Dionysodorus (early 2nd century bce), and Dionysodorus, according to Eutocius of Ascalon (c. 480–540 ce), used conic sections to complete a solution for Archimedes’ problem of cutting a sphere by a plane so that the ratio of the resulting volumes would be the same as a given ratio.

- ^ New Scientist | Technology | Roundest objects in the world created.

Further reading[edit]

- Albert, Abraham Adrian (2016) [1949], Solid Analytic Geometry, Dover, ISBN 978-0-486-81026-3.

- Dunham, William (1997). The Mathematical Universe: An Alphabetical Journey Through the Great Proofs, Problems and Personalities. Wiley. New York. pp. 28, 226. Bibcode:1994muaa.book…..D. ISBN 978-0-471-17661-9.

- Kreyszig, Erwin (1972), Advanced Engineering Mathematics (3rd ed.), New York: Wiley, ISBN 978-0-471-50728-4.

- Steinhaus, H. (1969), Mathematical Snapshots (Third American ed.), Oxford University Press.

- Woods, Frederick S. (1961) [1922], Higher Geometry / An Introduction to Advanced Methods in Analytic Geometry, Dover.

- John C. Polking (15 April 1999). “The Geometry of the Sphere”. www.math.csi.cuny.edu. Retrieved 21 January 2022.

External links[edit]

and is called the equation of an imaginary sphere. If

and is called the equation of an imaginary sphere. If  , the only solution of

, the only solution of  is the point

is the point  and the equation is said to be the equation of a point sphere. Finally, in the case

and the equation is said to be the equation of a point sphere. Finally, in the case

and whose radius is

and whose radius is  .[2]

.[2]

can be parameterized using trigonometric functions.

can be parameterized using trigonometric functions.

varies from 0 to 2

varies from 0 to 2

![{displaystyle V=pi left[r^{2}x-{frac {x^{3}}{3}}right]_{-r}^{r}=pi left(r^{3}-{frac {r^{3}}{3}}right)-pi left(-r^{3}+{frac {r^{3}}{3}}right)={frac {4}{3}}pi r^{3}.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/4c081de9760153a5ab7e59be1b9de1aa97d08dec)

. This can be found from the volume element in spherical coordinates with

. This can be found from the volume element in spherical coordinates with

satisfy the equation

satisfy the equation

and the cylinder with equation

and the cylinder with equation  is not just one or two circles. It is the solution of the non-linear system of equations

is not just one or two circles. It is the solution of the non-linear system of equations

Recent Comments