Tropolone – Wikipedia

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

|||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

2-Hydroxycyclohepta-2,4,6-trien-1-one |

|||

| Other names

2-Hydroxytropone; Purpurocatechol |

|||

| Identifiers | |||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChEMBL | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.007.799 | ||

| EC Number | |||

| KEGG | |||

| MeSH | D014334 | ||

| UNII | |||

|

|||

| Properties | |||

| C7H6O2 | |||

| Molar mass | 122.12 g/mol | ||

| Melting point | 50 to 52 °C (122 to 126 °F; 323 to 325 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 80 to 84 °C (176 to 183 °F; 353 to 357 K) (0.1 mmHg) | ||

| Acidity (pKa) | 6.89 (and -0.5 for conjugate acid) | ||

| -61·10−6 cm3/mol | |||

| Hazards | |||

| GHS labelling:[2] | |||

|

|||

| Danger | |||

| H314, H317, H410 | |||

| P260, P261, P264, P272, P273, P280, P301+P330+P331, P302+P352, P303+P361+P353, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P310, P333+P313, P363, P391, P405, P501 | |||

| Flash point | 112 °C (234 °F; 385 K) | ||

| Related compounds | |||

|

Related compounds |

Hinokitiol (4-isopropyl-tropolone) | ||

|

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

|

|||

Chemical compound

Tropolone is an organic compound with the chemical formula C7H5(OH)O. It is a pale yellow solid that is soluble in organic solvents. The compound has been of interest to research chemists because of its unusual electronic structure and its role as a ligand precursor. Although not usually prepared from tropone, it can be viewed as its derivative with a hydroxyl group in the 2-position.

Synthesis and reactions[edit]

Many methods have been described for the synthesis of tropolone.[3] One involves bromination of 1,2-cycloheptanedione with N-bromosuccinimide followed by dehydrohalogenation at elevated temperatures, while another uses acyloin condensation of the ethyl ester of pimelic acid the acyloin again followed by oxidation by bromine.[4]

An alternate route is a [2+2] cycloaddition of cyclopentadiene with a ketene to give a bicyclo[3.2.0]heptyl structure, followed by hydrolysis and breakage of the fusion bond to give the single ring:[3]

Thy hydroxyl group of tropolone is acidic, having a pKa of 7, which is in between that of phenol (10) and benzoic acid (4). The increased acidity compared to phenol is due to resonance stabilization with the carbonyl group, as a vinylogous carboxylic acid.[4]

The compound readily undergoes O-alkylation to give cycloheptatrienyl derivatives, which in turn are versatile synthetic intermediates.[5] With metal cations, it undergoes deprotonation to form a bidentate ligand, such as in the Cu(O2C7H5)2 complex.[4]

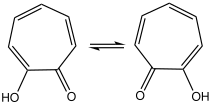

The carbonyl group is also highly polarized, as common for tropones. There can be substantial hydrogen bonding between it and the hydroxyl group, leading to rapid tautomerization: the structure is symmetric on the NMR timescale.[6]

Natural occurrence[edit]

Around 200 naturally occurring tropolone derivatives have been isolated, mostly from plants and fungi.[7] Tropolone compounds and their derivatives include dolabrins, dolabrinols, thujaplicins, thujaplicinols, stipitatic acid, stipitatonic acid, nootkatin, nootkatinol, puberulic acid, puberulonic acid, sepedonin, 4-acetyltropolone, pygmaein, isopygmaein, procein, chanootin, benzotropolones (such as purpurogallin, crocipodin, goupiolone A and B), theaflavin and derivatives bromotropolones, tropoisoquinolines and tropoloisoquinolines (such as grandirubrine, imerubrine, isoimerubrine, pareitropone, pareirubrine A and B), colchicine, colchicone and others.[8] Tropolone arises via a polyketide pathway, which affords a phenolic intermediate that undergoes ring expansion.[5]

They are especially found in specific plant species, such as Cupressaceae and Liliaceae families.[7] Tropolones are mostly abundant in the heartwood, leaves and bark of plants, thereby the essential oils are rich in various types of tropolones. The first natural tropolone derivatives were studied and purified in the mid-1930s and early-1940s.[9]Thuja plicata, Thujopsis dolabrata, Chamaecyparis obtusa, Chamaecyparis taiwanensis and Juniperus thurifera were in the list of trees from which the first tropolones were identified. The first synthetic tropolones were thujaplicins derived by Ralph Raphael.[10]

Biological effects[edit]

It is an inhibitor of grape polyphenol oxidase[11][12] and mushroom tyrosinase.[13]

Tropolone derivatives[edit]

| Class | Examples | Main natural sources[8][7][18][19] | Research directions[7][20][8][21][22] | Patented in products[7][23] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simple tropolones | Tropolone | Pseudomonas lindbergii, Pseudomonas plantarii | Antibacterial, antifungal, insecticidal, pesticidal, plant growth inhibition, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, neuroprotection, anti-protease, anti-browning (anti-tyrosinase and anti-polyphenol oxidase), antineoplastic, chelating | – |

| Dolabrins | β-dolabrin, α-dolabrinol | Caragana pygmaea, Cupressus goveniana, Cupressus abramsiana, Thujopsis dolabrata | Antibacterial, antifungal, insecticidal, pesticidal, plant growth inhibition, protease inhibition | Insect repellent, deodorant |

| Thujaplicins | α-thujaplicin, β-thujaplicin (hinokitiol), γ-thujaplicin, thujaplicinol | Chamaecyparis obtusa, Thuja plicata, Thujopsis dolabrata, Juniperus cedrus, Cedrus atlantica, Cupressus lusitanica, Chamaecyparis lawsoniana, Chamaecyparis taiwanensis, Chamaecyparis thyoides, Cupressus arizonica, Cupressus macnabiana, Cupressus macrocarpa, Cupressus guadalupensis, Juniperus chinensis, Juniperus communis, Juniperus californica, Juniperus occidentalis, Juniperus oxycedrus, Juniperus sabina, Calocedrus decurrens, Calocedrus formosana, Platycladus orientalis, Thuja occidentalis, Thuja standishii, Tetraclinis articulata, Cattleya forbesii, Carya glabra | Antifungal, antibacterial, anti-browning (anti-tyrosinase), chelating, insecticidal, pesticidal, antimalarial, antiviral, anti-inflammatory, plant growth inhibition, anti-protease, antidiabetic, antineoplastic, chemosensitizing, antioxidant, neuroprotection, veterinary medicine | Insect repellent, deodorant, toothpaste, oral spray, skin and hair care, wood preservative, food additive, food packaging |

| Sesquiterpene tropolones | Nootkatin, nootkatinol, nootkatol, nootkatene, valencene-13-ol, nootkastatin | Chamaecyparis nootkatensis, Grapefruit | Antifungal, anti-browning (anti-tyrosinase), insecticidal, fungicidal, antineoplastic | Insect repellents, flavor, perfumery |

| Pygmaeins | Pygmaein, Isopygmaein | Caragana pygmaea, Cupressus goveniana, Cupressus abramsiana | – | – |

| Benzotropolones | Purpurogallin, crocipodin, goupiolone A and B | Quercus species, Leccinum crocipodium, Goupia glabra | Antibacterial, plant growth inhibition, protease inhibition, antineoplastic, antimalarial, antioxidant, antiviral | Food additive |

| Theaflavins | Theaflavin, theaflavic acid, theaflavate A and B | Camellia sinensis, Quercus species | Antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antiviral, antidiabetic, chemosensitizing | – |

| Tropoisoquinolines and tropoloisoquinolines | Grandirubrine, imerubrine, isoimerubrine, pareitropone, pareirubrine A and B | Cissampelos pareira, Abuta grandifolia | Antileukemic | – |

| Tropone alkaloids | Colchicine, demecolcine | Colchicum autumnale, Gloriosa superba | Antimitotic, anti-inflammatory, anti-gout, plant breeding | Pharmaceutical drug |

References[edit]

- ^ Tropolone[permanent dead link] at Sigma-Aldrich

- ^ “Tropolone”. pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

- ^ a b Minns, Richard A. (1977). “Tropolone”. Org. Synth. 57: 117. doi:10.15227/orgsyn.057.0117.

- ^ a b c Pauson, Peter L. (1955). “Tropones and Tropolones”. Chem. Rev. 55 (1): 9–136. doi:10.1021/cr50001a002.

- ^ a b Pietra, F. (1973). “Seven-membered conjugated carbo- and heterocyclic compounds and their homoconjugated analogs and metal complexes. Synthesis, biosynthesis, structure, and reactivity”. Chemical Reviews. 73 (4): 293–364. doi:10.1021/cr60284a002.

- ^ Jin, Lehong (February 1987). Detoxification of thujaplicins in living western red cedar (Thuja plicata Donn.) trees by microorganisms (PhD). University of British Columbia.

- ^ a b c d e Zhao, Jian Zhao and Jian (30 September 2007). “Plant Troponoids: Chemistry, Biological Activity, and Biosynthesis”. Current Medicinal Chemistry. 14 (24): 2597–2621. doi:10.2174/092986707782023253. PMID 17979713.

- ^ a b c Liu, Na; Song, Wangze; Schienebeck, Casi M.; Zhang, Min; Tang, Weiping (December 2014). “Synthesis of naturally occurring tropones and tropolones”. Tetrahedron. 70 (49): 9281–9305. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2014.07.065. PMC 4228802. PMID 25400298.

- ^ Nakanishi, Koji (June 2013). “Tetsuo Nozoe’s “Autograph Books by Chemists 1953-1994”: An Essay: Tetsuo Nozoe’s “Autograph Books by Chemists 1953-1994″: An Essay”. The Chemical Record. 13 (3): 343–352. doi:10.1002/tcr.201300007. PMID 23737463.

- ^ Cook, J. W.; Raphael, R. A.; Scott, A. I. (1951). “149. Tropolones. Part II. The synthesis of α-, β-, and γ-thujaplicins”. J. Chem. Soc.: 695–698. doi:10.1039/JR9510000695.

- ^ Time-dependent inhibition of grape polyphenol oxidase by tropolone. Edelmira Valero, Manuela Garcia-Moreno, Ramon Varon and Francisco Garcia-Carmona, J. Agric. Food Chem., 1991, volume 39, pp. 1043–1046, doi:10.1021/jf00006a007

- ^ Chedgy, Russell. Secondary metabolites of Western red cedar (Thuja plicata): their biotechnological applications and role in conferring natural durability. LAP Lambert Academic Publishing, 2010, ISBN 3-8383-4661-0, ISBN 978-3-8383-4661-8

- ^ Inhibition of mushroom tyrosinase by tropolone. Varda Kahn and Andrawis Andrawis, Phytochemistry, Volume 24, Issue 5, 1985, Pages 905-908, doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)83150-7

- ^ Liu, Na; Song, Wangze; Schienebeck, Casi M.; Zhang, Min; Tang, Weiping (December 2014). “Synthesis of naturally occurring tropones and tropolones”. Tetrahedron. 70 (49): 9281–9305. doi:10.1016/j.tet.2014.07.065. PMC 4228802. PMID 25400298.

- ^ Saniewski, Marian; Horbowicz, Marcin; Kanlayanarat, Sirichai (10 September 2014). “The Biological Activities of Troponoids and Their Use in Agriculture A Review”. Journal of Horticultural Research. 22 (1): 5–19. doi:10.2478/johr-2014-0001.

- ^ Davison, J.; al Fahad, A.; Cai, M.; Song, Z.; Yehia, S. Y.; Lazarus, C. M.; Bailey, A. M.; Simpson, T. J.; Cox, R. J. (15 May 2012). “Genetic, molecular, and biochemical basis of fungal tropolone biosynthesis”. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 109 (20): 7642–7647. doi:10.1073/pnas.1201469109. PMC 3356636. PMID 22508998.

- ^ Keith, Michael P.; Gilliland, William R.; Uhl, Kathleen (2009). “GOUT”. Pharmacology and Therapeutics: 1039–1046. doi:10.1016/B978-1-4160-3291-5.50079-2. ISBN 9781416032915.

- ^ Karchesy, Joseph J.; Kelsey, Rick G.; González-Hernández, M. P. (May 2018). “Yellow-Cedar, Callitropsis (Chamaecyparis) nootkatensis, Secondary Metabolites, Biological Activities, and Chemical Ecology”. Journal of Chemical Ecology. 44 (5): 510–524. doi:10.1007/s10886-018-0956-y. PMID 29654493. S2CID 4839697.

- ^ Goldfrank’s toxicologic emergencies. Nelson, Lewis, 1963- (Eleventh ed.). New York. 11 April 2019. ISBN 978-1-259-85961-8. OCLC 1020416505.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Carlsson, Blenda; Erdtman, H.; Frank, A.; Harvey, W. E.; Östling, Sven (1952). “The Chemistry of the Natural Order Cupressales. VIII. Heartwood Constituents of Chamaecyparis nootkatensis – Carvacrol, Nootkatin, and Chamic Acid”. Acta Chemica Scandinavica. 6: 690–696. doi:10.3891/acta.chem.scand.06-0690.

- ^ Dalbeth, Nicola; Lauterio, Thomas J.; Wolfe, Henry R. (October 2014). “Mechanism of Action of Colchicine in the Treatment of Gout”. Clinical Therapeutics. 36 (10): 1465–1479. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2014.07.017. PMID 25151572.

- ^ Griffiths AJF, Gelbart WM, Miller JH (1999). “Modern Genetic Analysis: Changes in Chromosome Number”. Modern Genetic Analysis. W. H. Freeman, New York.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ US EPA, OCSPP (10 August 2020). “Nootkatone Now Registered by EPA”. US EPA.

Recent Comments