Five Tathāgatas – Wikipedia

Representations of the five qualities of the Adi-Buddha

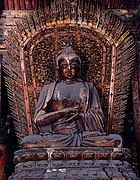

In Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism, the Five Tathāgatas (Sanskrit: पञ्चतथागत, pañcatathāgata; Chinese: 五方佛; pinyin: Wǔfāngfó) or Five Wisdom Tathāgatas (Chinese: 五智如来; pinyin: Wǔzhì Rúlái), the Five Great Buddhas, the Five Dhyani Buddhas and the Five Jinas (Sanskrit for “conqueror” or “victor”), are five Buddhas which are often venerated together. Various sources provide different names for these Buddhas, though the most common today are: Akshobhya, Ratnasambhava, Vairocana, Amitābha, and Amoghasiddhi.[1]

They are sometimes seen as emanations and representations of the five qualities of the Adi-Buddha or “first Buddha”, which is associated with the Dharmakāya.[1] Some sources also include this “first Buddha” as a sixth Buddha along with the five.[1]

These five Buddhas are a common subject of Vajrayana mandalas and they feature prominently in various Buddhist Tantras. The Five Tathagathas are the primary object of realization and meditation in Shingon Buddhism, a school of Vajarayana Buddhism founded in Japan by Kūkai.

In Chinese Buddhism, veneration of the five Buddhas have dispersed from Chinese Esoteric Buddhism into the other Chinese Buddhist traditions like Chan and Tiantai. They are regularly enshrined in many Chinese Buddhist temples and regularly invoked in rituals, such as the Liberation Rite of Water and Land and the Yoga Flaming Mouth ceremony (瑜伽焰口法會), as well as prayers and chants.[2][3]

They are also sometimes called the “dhyani-buddhas”, a term first recorded in English by Brian Houghton Hodgson, a British Resident in Nepal,[4] in the early 19th century, and is unattested in any surviving traditional primary sources.[5]

The Five Wisdom Buddhas are a development of the Buddhist Tantras, and later became associated with the trikaya or “three body” theory of Buddhahood. While in the Tattvasaṃgraha Tantra there are only four Buddha families, the full Diamond Realm mandala with five Buddhas first appears in the Vajrasekhara Sutra.[1]

Representations of the five Dhyani Buddhas, who are abstract aspects of Buddhahood rather than Buddhas or gods, have elaborate differences.[6] Each must face in a different direction (north, south, east, west, or center), and, when painted, each is a different color (blue, yellow, red, green, or white). Each has a different mudrā and symbol; embodies a different aspect, type of evil, and cosmic element; has a different consort and spiritual son, as well as different animal vehicles (elephant, lion, peacock, harpys or garuda, or dragon).[7]

The Vajrasekhara also mentions a sixth Buddha, Vajradhara, “a Buddha (or principle) seen as the source, in some sense, of the five Buddhas.”[1]

The Five Buddhas are aspects of the dharmakaya “dharma-body”, which embodies the principle of enlightenment in Buddhism.

Initially, two Buddhas appeared to represent wisdom and compassion: Akshobhya and Amitābha. A further distinction embodied the aspects of power, or activity, and the aspect of beauty, or spiritual riches. In the Golden Light Sutra, an early Mahayana text, the figures are named Dundubishvara and Ratnaketu, but over time their names changed to become Amoghasiddhi, and Ratnasambhava. The central figure came to be called Vairocana.

Vairocana, the first Dhyani Buddha, embodies sovereignty. [7] Japanese Pure Land Buddhists think that Vairocana and the other Dhyani Buddhas are manifestations of Amitābha, but Japanese Shingon Buddhists think that Amitābha and the other Dhyani Buddhas are manifestations of Vairocana.[8]

Akshobhya, the second Dhyani Buddha who embodies steadfastness and faces east. He is seated in the Vajraparyanka (also known as Bhūmisparśa) pose, with the right hand on the right knee, palm turned inwardly, and middle finger touching the ground.[7][9][10]

Amitābha (Japanese: Amida) is the most ancient Dhyani Buddha, embodying light and facing west, and is the central figure in Pure Land Buddhism. A statue of Amitābha, when seated, has a samadhi mudrā with both palms face up, on top of each other, in his lap.[7][11][12]

When these Buddhas are represented in mandalas, they may not always have the same colour or be related to the same directions. In particular, Akshobhya and Vairocana may be switched. When represented in a Vairocana mandala, the Buddhas are arranged like this:

The Five Families or Divisions and their qualities[edit]

There is an expansive number of associations with each element of the five Buddhas mandala, so that the mandala becomes a cipher and mnemonic visual thinking instrument and concept map; a vehicle for understanding and decoding the whole of the Dharma. Each Buddha Family or Division has numerous symbols, secondary figures (like bodhisattvas, protectors, etc.), powers and aspects.

Some of the associations include:

| Family (Kula) | Buddha | Colour ← Element → Symbolism | Cardinality → Wisdom → Attachments → Gestures | Means → Maladaptation to Stress | Season | Wisdom |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buddha Family | Vairocana | white ← space → wheel | center → all accommodating → rūpa → Teaching the Dharma | Turning the Wheel of Dharma → ignorance, delusion | n/a | 法界体性智: The wisdom of the essence of the dharma-realm meditation mudra.[13] |

| Karma Family | Amoghasiddhi | green ← air, wind → viśvavajra | north → all accomplishing → mental formation, concept → fearlessness | protect, destroy → envy, jealousy | spring | 成所作智: The wisdom of perfect practice. |

| Padma (Lotus) Family | Amitābha | red ← fire → lotus | west → inquisitive → perception → meditation | magnetize, attachment → selfishness,

subjugate |

summer | 妙観察智: The wisdom of observation. |

| Ratna (Jewel) Family | Ratnasambhava | gold/yellow ← earth → jewel | south → equanimous → feeling → giving | enrich, increase → pride, greed | autumn | 平等性智: The wisdom of equanimity. |

| Vajra Family | Akṣobhya | blue ← water → sceptre, vajra | east → nondualist → vijñāna → humility | pacify, accept → aggression, aversion | winter | 大円鏡智: The wisdom of reflection. |

The five Tathāgathas are protected by five Wisdom Kings, and in China and Japan are frequently depicted together in the Mandala of the Two Realms. In the Śūraṅgama santra revealed in the Śūraṅgama sutra, an especially influential dharani in the Chinese Chan tradition, the five Tathāgathas are mentioned as the hosts of the five divisions which controls the vast demon armies of the five directions.[14]

- In the East is the Vajra Division, hosted by Akṣobhya

- In the South, the Jewel-creating Division, hosted by Ratnasaṃbhava

- In the center, the Buddha Division, hosted by Vairocana

- In the West, the Lotus Division, hosted by Amitābha

- In the North, the Karma Division, hosted by Amoghasiddhi

In East Asia, they each are also often depicted with consorts, and preside over their own pure lands, with the aspiration to be reborn into a pure land being the central point of Pure Land Buddhism. Although all five Buddhas have pure lands, it appears that only Sukhavati of Amitābha, and to a much lesser extent Abhirati of Akshobhya (where great masters like Vimalakirti and Milarepa are said to dwell) attracted aspirants.

Gallery[edit]

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

-

Painting of the Five Buddhas, circa the 6th year under Injo of Joseon Dynasty (1628), Korea

-

Gilt copper crown with five buddhas, Tibet, 1644-1911 CE.

-

Ritual Diadem with the Five Jina Buddhas, Northern Nepal or Tibet, 19th century

-

Five Buddhas, Nepal, 16th century

-

Statues of the Five Tathagathas, Tri Ratna Buddhist Centre, Pekanbaru, Sumatra

-

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Williams, Wynne, Tribe; Buddhist Thought: A Complete Introduction to the Indian Tradition, page 210.

- ^ “香光莊嚴”. www.gaya.org.tw. Retrieved 2021-05-12.

- ^ Hong, Tsai-Hsia (2007). The Water-Land Dharma Function Platform Ritual and the Great Compassion Repentance Ritual (Thesis). OCLC 64281400. ProQuest 304764751.

- ^ Bogle (1999) pp. xxxiv-xxxv

- ^ Saunders, E Dale, “A Note on Śakti and Dhyānibuddha,” History of Religions 1 (1962): pp. 300-06.

- ^ Sakya, pp. 35, 76.

- ^ a b c d Sakya, p. 76.

- ^ Getty, Alice (1914). The gods of northern Buddhism: their history, iconography and progressive evolution through the northern Buddhist countries. Oxford Clarendon Press via Internet Archive. p. 3.

- ^ “The Lotus Sutra focus on Śākyamuni also fits the main Buddha figure in Zen, rather than the Buddhas Amida or Vairocana venerated in the contemporary

Pure Land and Esoteric (and Kegon) movements.” in Taigen Dan Leighton (2005). “Dōgen’s Appropriation of Lotus Sutra Ground and Space”. Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. Nanzan University. 32 (1): 87. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195320930.003.0004. JSTOR 30233778. - ^ “One of the two wives of Songtsen Gampo, she brought a large image of either Shakyamuni or Akshobhya Buddha (they are visually

indistinguishable)…” in “Glossary (Balza, Balmoza)” (PDF). The Huntington Archive, Ohio State University. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 9, 2011. Retrieved January 22, 2012. - ^ Sakya, p. 30.

- ^ Similarities with Amitabha in “Who’s Who of Buddhism”. Vipassana Foundation. Archived from the original on January 11, 2009. Retrieved January 14, 2011.

- ^ Japanese Architecture and Art Net Users System. (2004). JAANUS / hokkai jouin 法界定印. Available: http://www.aisf.or.jp/~jaanus/deta/h/hokkaijouin.htm Archived 2013-12-03 at the Wayback Machine. Last accessed 27 Nov 2013.

- ^ The Śūraṅgama sūtra : a new translation. Hsüan Hua, Buddhist Text Translation Society. Ukiah, Calif: Buddhist Text Translation Society. 2009. ISBN 978-0-88139-962-2. OCLC 300721049.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link)[page needed] - ^ “Pandara The Shakti of Amitabha”. Buddhanature.com. Retrieved 2013-06-14.

- ^ “Mamaki The Shakti of Aksobhya”. Buddhanature.com. Retrieved 2013-06-14.

- ^ “chart of the Five Buddhas and their associations”. Religionfacts.com. 2012-12-21. Retrieved 2013-06-14.

- ^ Symbolism of the five Dhyani Buddhas Archived March 8, 2009, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Longchenpa (2014). “XIII”. The Great Chariot. p. Part 3e.2a.

- ^ Shumsky, Susan (2010). Ascension: Connecting with the Immortal Masters and Beings of Light. Red Wheel/Weiser. ISBN 978-1-60163-092-6.

Bibliography[edit]

- Bogle, George; Markham, Clements Robert; and Manning, Thomas (1999) Narratives of the Mission of George Bogle to Tibet and of the Journey of Thomas Manning to Lhasa ISBN 81-206-1366-X

- Bucknell, Roderick & Stuart-Fox, Martin (1986). The Twilight Language: Explorations in Buddhist Meditation and Symbolism. Curzon Press: London. ISBN 0-312-82540-4

- Sakya, Jnan Bahadur (compiler) (2002) [1995]. Short Description of Gods, Goddesses and Ritual Objects of Buddhism and Hinduism in Nepal (10th [reprint] ed.). Handicraft Association of Nepal. ISBN 99933-37-33-1.

External links[edit]

Recent Comments