Patrick McHenry – Wikipedia

American politician (born 1975)

|

Patrick McHenry |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Assumed office January 3, 2023 |

|

| Preceded by | Maxine Waters |

| In office January 3, 2019 – January 3, 2023 |

|

| Preceded by | Maxine Waters |

| Succeeded by | Maxine Waters |

| In office August 1, 2014 – January 3, 2019 |

|

| Leader | John Boehner Paul Ryan |

| Preceded by | Peter Roskam |

| Succeeded by | Drew Ferguson |

| Assumed office January 3, 2005 |

|

| Preceded by | Cass Ballenger |

| In office January 1, 2003 – January 1, 2005 |

|

| Preceded by | Constituency established |

| Succeeded by | William Current |

| Born |

Patrick Timothy McHenry October 22, 1975 |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse |

Giulia Cangiano (m. 2010) |

| Children | 3 |

| Education | North Carolina State University Belmont Abbey College (BA) |

| Website | House website |

Patrick Timothy McHenry (born October 22, 1975) is the U.S. representative for North Carolina’s 10th congressional district, serving since 2005. He is a member of the Republican Party. The district includes the cities of Hickory and Mooresville. McHenry was a member of the North Carolina House of Representatives for a single term.

McHenry served as a House Republican chief deputy whip from 2014 to 2019, ranking member of the House Financial Services Committee from 2019 to 2023, and chair of the House Financial Services Committee since 2023.[1][2]

Early life, education, and career[edit]

McHenry was born in Gastonia, North Carolina. He grew up in suburban Gastonia, the son of the owner of the Dixie Lawn Care Company,[3] and attended Ashbrook High School.[4] A Roman Catholic, he was the youngest of five children.

McHenry attended North Carolina State University before transferring to Belmont Abbey College.[3] At Belmont, he founded the school’s College Republican chapter,[3] then became chair of the North Carolina Federation of College Republicans and treasurer of the College Republican National Committee.

In 1998, while a junior in college, McHenry ran for the North Carolina House of Representatives. He won the Republican primary but lost the general election.

After earning a B.A. in history in 1999, McHenry worked for the media consulting firm DCI/New Media, in Washington, D.C. He was involved in Rick Lazio’s campaign in the 2000 United States Senate election in New York; his main project was running a Web site, NotHillary.com.[3] In 2012, he received an honorary M.B.A. in entrepreneurship from Yorktown University.[5]

Early political career[edit]

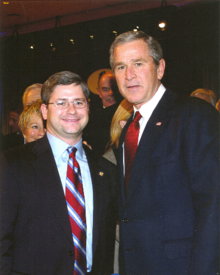

In mid-2000, Karl Rove hired McHenry to be the National Coalition Director for George W. Bush’s 2000 presidential campaign.[3] In late 2000 and early 2001, he was a volunteer coordinator for Bush’s inaugural committee. After working for six months in 2001 as a special assistant to Elaine Chao, the United States Secretary of Labor, McHenry returned to North Carolina and ran again for the North Carolina General Assembly, winning in the 2002 election.[6]

A resident of Denver, North Carolina, McHenry represented the state’s 109th House district, including constituents in Gaston County, for the 2003–04 session. He sat on the House Appropriations Committee.

U.S. House of Representatives[edit]

Committee assignments[edit]

Caucus memberships[edit]

At age 33, McHenry was the youngest member of the 110th United States Congress; 27-year-old Aaron Schock of Illinois took office in the 111th United States Congress in January 2009.[needs update] He is a deputy whip and vice chair of finance for the National Republican Congressional Committee’s executive committee.[9]

[edit]

McHenry stirred controversy with remarks on April 1, 2008, regarding a trip to Iraq. Speaking to 150 Republicans attending the Lincoln County GOP Dinner, he called a contractor, reported first by blogs as a “U.S. soldier”[10] – performing security duties in Iraq “a two-bit security guard” because the contractor denied McHenry access to a gym.

We spent the night in the Green Zone, in the poolhouse of one of Saddam’s palaces. A little weird, I got to be honest with you. But I felt safe. And so in the morning, I got up early – not that I make this a great habit – but I went to the gym because I just couldn’t sleep and everything else. Well, sure enough, the guard wouldn’t let me in. Said I didn’t have the correct credentials. It’s 5:00 in the morning. I haven’t had sleep. I was not very happy with this two-bit security guard. So you know, I said, “I want to see your supervisor.” Thirty minutes later, the supervisor wasn’t happy with me, they escort me back to my room. It happens. I guess I didn’t need to work out anyway.[11][12]

He later apologized, saying, “it was a poor choice of words.”[13]

Baghdad video[edit]

McHenry was the subject of discussion regarding a video posted on his congressional campaign website that featured him in the Green Zone in Baghdad, pointing out landmarks and destruction after missile attacks. Veteran’s affairs blog VetVoice posted a scathing attack, claiming that McHenry’s video violated Operational Security.[14] McHenry later removed the video after discussing the information with the Pentagon, which requested he not place the video back online.[15] Lance Sigmon, McHenry’s opponent, later called a press conference to demand an investigation of the video’s effect on Green Zone Troops.[16][full citation needed] Sigmon attacked McHenry in a campaign ad about this controversy, prompting McHenry to threaten legal action, claiming the ad was false.

Use of PAC funds[edit]

On April 16, 2008, Roll Call reported that McHenry used funds from his political action committee (PAC), “More Conservatives”, to fund the defense of former aide Michael Aaron Lay’s voter fraud charges incurred during McHenry’s 2004 race.[17] McHenry gave Lay $20,000 to pay legal bills on voter fraud charges brought while Lay worked for him.[17] These expenses were labeled a “Legal Expense Donation”, according to Federal Election Commission reports. Lay agreed to a deferred prosecution agreement, which stipulated he complete 100 hours of community service and pay $240.50 in court fees and $250 in community service fees to have the charges dismissed.[citation needed] An employee of the 2004 campaign, Lay lived in McHenry’s home in Cherryville, which also served as the campaign headquarters during the 2004 election, and was indicted for voter fraud in McHenry’s election, allegedly voting illegally in two separate instances.[18] In response, McHenry claimed the case was part of a “three-year smear campaign” by District Attorney Locke Bell,[19] despite Bell fund-raising for McHenry in previous elections.[20][full citation needed]

Countrywide donations[edit]

OpenSecrets’ Capital Eye found evidence that McHenry had been taking money from Countrywide Financial, a company involved in the subprime mortgage crisis.[21] McHenry took $5,500 from Countrywide’s PAC, and served in an investigation into CEO payout fraud, of which one of the target companies was Countrywide Financial itself.

Elizabeth Warren[edit]

On May 24, 2011, Elizabeth Warren, appointed by President Obama to oversee the development of the new U.S. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), attended a House subcommittee meeting chaired by McHenry, who invited her because he felt she had given misleading testimony during another hearing. Earlier that day, McHenry had appeared on CNBC and accused Warren of lying to Congress about her involvement in government inquiries into mortgage servicing.[22]

The meeting had several late and last-minute changes, so Warren altered her schedule to accommodate the chair’s request. Around 2:15 pm, McHenry called for a temporary recess to partake in a floor vote. In response, Warren indicated that McHenry’s staff had agreed to the 2:15 pm closing time to allow her ample time to attend another meeting. McHenry replied, “You had no agreement. … You’re making this up, Ms. Warren. This is not the case.” As Warren and some in the audience reacted with surprise, Representative Elijah Cummings interjected, “Mr. Chairman … I’m trying to be cordial here, but you just accused the lady of lying. I think you need to clear this up with your staff.”[23]

The CFPB confirmed the agreement, but McHenry refused to apologize for his remarks to Warren.[24]

The Hickory Daily Record, the largest paper in McHenry’s district, called for McHenry to apologize, saying that it was “unacceptable for any member of Congress, especially a subcommittee chairman” to treat a witness in the manner in which he treated Warren.[25]

Payday lenders[edit]

McHenry supported a 2020 rule change by the Trump administration whereby payday lenders would no longer have to check whether prospective borrowers can afford to repay high-interest loans.[26]

2020 presidential election[edit]

McHenry did not join the majority of Republican members of Congress who sided with the Trump campaign’s attempts to overturn the 2020 United States presidential election. He voted in favor of certifying both Arizona’s and Pennsylvania’s votes in the 2021 United States Electoral College vote count.[citation needed]

Political campaigns[edit]

2004[edit]

In 2004, after one term in the North Carolina General Assembly, McHenry ran for Congress in the 10th Congressional district when nine-term incumbent Cass Ballenger retired. McHenry faced a heavily contested primary and bested his closest opponent, Catawba County Sheriff David Huffman, in a runoff by only 85 votes.

In the general election, McHenry won 64% of the popular vote, defeating Democrat Anne Fischer. It was generally thought McHenry’s victory in the primary runoff was tantamount to election in November: his district is considered North Carolina’s most Republican district, having sent Republicans to represent it since 1963.

2006[edit]

In the 2006 election, McHenry defeated Democrat Richard Carsner with almost 62% of the vote.

2008[edit]

In 2008, McHenry defeated Lance Sigmon in the Republican primary with 67% of the vote, and faced Democrat Daniel Johnson in the general election. Johnson was considered the strongest and best-funded Democrat to run in the district in over 20 years. In part because of this, the Cook Political Report moved the race from “Safe Republican” to “Likely Republican.” This meant that in Charlie Cook’s opinion, while McHenry still had a considerable advantage, a victory by Johnson could not be ruled out. Shortly after the Cook Political Report’s update, Stuart Rothenberg of the Rothenberg Political Report, also a nonpartisan analysis of American politics and elections, addressed the race and indicated his opinion that an upset was unlikely.[27] McHenry defeated Johnson, 58% to 42%.[28]

2010[edit]

McHenry defeated Republicans Vance Patterson, Scott Keadle, and David Michael Boldon with 63.09% of the vote to win the primary.[29] He defeated Democrat Jeff Gregory with 71.18% of the vote in the general election.[30]

2012[edit]

McHenry defeated Ken Fortenberry and Don Peterson with 72.54% of the vote in the primary.[31] He defeated Democrat Patsy Keever in the general election with 56.99% of the vote.[32]

2014[edit]

McHenry defeated Richard Lynch in the primary with 78.04% of the vote.[33] He defeated Democrat Tate MacQueen with 61.02% of the vote in the general election.[34]

2016[edit]

McHenry defeated Jeff Gregory, Jeffrey Baker, and Albert Lee Wiley Jr. with 78.42% of the vote in the primary.[35] He defeated Democrat Andy Millard with 63.14% of the vote in the general election.[36]

2018[edit]

McHenry defeated a host of fellow Republicans in the primary with 70.72% of the vote.[37] He defeated Democrat David Wilson Brown with 59.29% percent of the vote in the general election.[38]

2020[edit]

McHenry defeated David Johnson and Ralf Walters in the primary with 71.67% of the vote.[39] He defeated Democrat David Parker with 68.91% of the vote in the general election.[40]

2022[edit]

McHenry defeated five opponents in the primary with 68.1% of the vote.[41] He defeated Democrat Pam Genant with 72.6% of the vote in the general election.[42]

References[edit]

- ^ Neukam, Stephen (10 January 2023). “New Congress: Here’s who’s heading the various House Committees”. The Hill. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- ^ Duster, Chandelis (4 January 2023). “The lawmaker trying to unite Republicans around McCarthy’s speakership bid”. CNN. Retrieved 11 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Benjamin Wallace-Wells (October–November 2005). “Getting Ahead in the GOP; Rep. Patrick McHenry and the art of defending the indefensible”. Washington Monthly. Archived from the original on 2009-07-04.

- ^ “Alumni Network | Close Up Foundation | Educational Programs”. Close Up Foundation. Retrieved 2020-06-24.

- ^ Wade Shol, Cong. Patrick McHenry (R-NC) honored by honorary MBA in Entrepreneurship, Press Release, June 12, 2012

- ^ “The New Members of the House”. Roll Call. 5 November 2004. Retrieved 2020-06-24.

- ^ “Member List”. Republican Study Committee. Retrieved 21 December 2017.

- ^ “Members”. Congressional NextGen 9-1-1 Caucus. Archived from the original on 12 June 2018. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ Chairman Tom Cole Announces 2007–2008 NRCC Executive Committee Archived 2008-08-07 at the Library of Congress Web Archives

- ^ “Rep. McHenry calls U.S. soldier in Iraq a ‘two-bit security guard.’ – ThinkProgress”. ThinkProgress. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ McHenry Refers to Soldier as “Two Bit Security Guard”, Carolina Politics Online, April 3, 2008

- ^ Video of Patrick McHenry’s “two-bit soldier” remark on YouTube

- ^ “Lawmaker apologizes for comment on Iraq guard – Army News, opinions, editorials, news from Iraq, photos, reports – Army Times”. armytimes.com. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ “VetVoice: Congressman McHenry Violates OPSEC; Endangers Troops”. vetvoice.com. Archived from the original on 12 December 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ ““Iraq visit hurts congressman” : News-Record.com : Greensboro, North Carolina”. 2008-04-11. Archived from the original on 2008-04-11. Retrieved 2018-10-23.

- ^ “Charlotte Observer | 04/19/2008 | GOP rival calls for probe of McHenry’s Iraq video”. Archived from the original on 2008-06-26. Retrieved 2008-04-19.[full citation needed]

- ^ a b “Necessary Overhead?”. Roll Call. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ Rey, Michael (May 11, 2007). “Congressman McHenry’s Campaign Aide Indicted”. CBS News.

- ^ Breaking News: McHenry campaign aide indicted for voter fraud from 2004 election, mchenry, lay, news : The Star Online : The Newspaper of Cleveland County Archived 2008-11-20 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ [1][permanent dead link][full citation needed]

- ^ OpenSecrets | Countrywide’s Campaign Contributions Weren’t Loans, But They Were Investments – Capital Eye Archived 2008-11-18 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wyatt, Edward (May 24, 2011). “Decorum Breaks Down at House Hearing”. The New York Times.

- ^ “Chairman McHenry Calls Elizabeth Warren a Liar at Subcommittee Hearing”. YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-12.

- ^ McAuliff, Michael (May 24, 2011). “Elizabeth Warren Called Liar At CFPB Hearing By Republicans Who Botched Facts On Agency (VIDEO)”. Huffington Post.

- ^ “EDITORIAL: McHenry should apologize to voters”. Hickory Daily Record. Archived from the original on June 1, 2011. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- ^ “Payday lenders won’t have to check whether borrowers can afford loans”. www.cbsnews.com. Retrieved 2020-07-07.

- ^ “The Rothenberg Political Report[FeedShow RSS reader]”. feedshow.com. Archived from the original on 20 February 2015. Retrieved 19 February 2015.

- ^ “2008 General Elections: Reports (unofficial results)”. North Carolina State Board of Elections. November 6, 2008. Retrieved November 7, 2008.

- ^ “US House of Representatives District 10 Primary Results 2010”. North Carolina State Board of Elections. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ “US House of Representatives District 10 Results 2010”. North Carolina State Board of Elections. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ “US House of Representatives District 10 Primary Results 2012”. North Carolina State Board of Elections. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ “US House of Representatives District 10 Results 2012”. North Carolina State Board of Elections. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ “US House of Representatives District 10 Primary Results 2014”. North Carolina State Board of Elections. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ “US House of Representatives District 10 Results 2014”. North Carolina State Board of Elections. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ “US House of Representatives District 10 Primary Results 2016”. North Carolina State Board of Elections. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ “US House of Representatives District 10 Results 2016”. North Carolina State Board of Elections. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ “US House of Representatives District 10 Primary Results 2018”. North Carolina State Board of Elections. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ “US House of Representatives District 10 Results 2018”. North Carolina State Board of Elections. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ “US House of Representatives District 10 Primary Results 2020”. North Carolina State Board of Elections. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ “US House of Representatives District 10 Results 2020”. North Carolina State Board of Elections. Retrieved 19 March 2021.

- ^ “05/17/2022 OFFICIAL LOCAL ELECTION RESULTS – STATEWIDE”. North Carolina State Board of Elections. Retrieved May 22, 2022.

- ^ “11/08/2022 OFFICIAL LOCAL ELECTION RESULTS – STATEWIDE”. North Carolina State Board of Elections.

External links[edit]

Recent Comments