Founding myth of Marseille – Wikipedia

Ancient origin myth

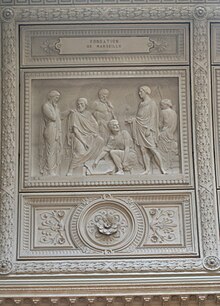

The founding myth of Marseille is an ancient creation myth telling the legendary foundation of the colony of Massalia (modern Marseille), on the Mediterranean coast of what was later known as southern Gaul, by Greek settlers from Phocaea, a city in western Anatolia. Although the attested versions differ on some details, they all recount the story of the marriage of the princess Gyptis (or Petta), the daughter of Nannus, chief of the native Segobrigii, to the Phocaean sailor Protis (or Euxenus). On her wedding day, the princess chooses to marry the foreigner by giving him a bowl filled with wine or water during the feast.

Only two extensive sources have survived: the story recounted by Aristotle in “The Constitution of the Massaliotes”, which is reproduced in Athenaeus’ Deipnosophistae, and the version told by Gallo-Roman historian Pompeius Trogus in his Philippic Histories, now lost but later summarized by the Roman historian Justin. The Roman historian Livy also alludes to the myth in his Ab Urbe Condita.

The motif of the princess choosing her future husband in a group of suitors during her wedding is found in other Indo-European myths, notably in the ancient Indian svayamvara tales and in Chares of Mytilene’s “Stories about Alexander”. The background of the Phocaean version was probably influenced by the actual founding of the colony of Massalia around 600 BC by Greek settlers from the Ionian city of Phocaea, although earlier prototypes may have existed already in Phocaea. The modern inhabitants of Marseille are still colloquially called the ‘Phocaeans’ (French: Phocéens).

Versions[edit]

Aristotle[edit]

Aristotle’s “Constitution of the Massaliotes”, written in the 4th century BC and later reproduced by Athenaeus in his Deipnosophistae, is a brief and elliptic summary of the foundation myth. The text is poorly transmitted and, according to philologist Didier Pralon, “the story looks more like a working note than a composed narrative”.

The Phocaeans who inhabit Ionia were traders and founded Massalia. Euxenus of Phocaea was a guest-friend of King Nanos—which was actually his name. Euxenus happened to be visiting when this Nanos was celebrating his daughter’s wedding, and he was invited to the feast. The wedding was organized as follows: After the meal, the girl had to come in and offer a bowl full of wine mixed with water to whichever suitor there she wanted, and whoever she gave it to would be her bridegroom. When the girl entered the room, she gave the bowl, either by accident or for some other reason, to Euxenus; her name was Petta. After this happened, and her father decided that the gift had been made in accord with the god’s will, so that he ought to have her, Euxenus married and set up housekeeping with her, although he changed her name to Aristoxene. There is still a family in Massalia today descended from her and known as the Protiadae; because Protis was the son of Euxenus and Aristoxene.

— Athenaeus 2010, XIII, fr. 549 Rose = Aristotle “Constitution of the Massaliotes”.

Pompeius Trogus[edit]

The version of Pompeius Trogus, a Gallo-Roman writer from the nearby Vocontian tribe, is now lost, but was summarized in the 3rd–4th century AD by the Roman historian Justin in his Epitoma Historiarum Philippicarum . Trogus was presumably repeating the version that was current in Massalia in the 1st century BC.

In the time of King Tarquin a party of young Phocaean warriors, sailing to the mouth of the Tiber, entered into an alliance with the Romans. From there, sailing into the distant bays of Gaul, they founded Massilia among the Ligurians and the fierce tribes of the Gauls; and they did mighty deeds, whether in protecting themselves against the savagery of the Gauls or in provoking them to fight—having themselves first been provoked. For the Phocaeans were forced by the meanness and poverty of their soil to pay more attention to the sea than to the land: they eked out an existence by fishing, by trading, and largely by piracy, which in those days was reckoned honourable. So they dared to sail to the furthest shore of the ocean and came to the Gallic gulf, by the mouth of the Rhone. Taken by the pleasantness of the place, they returned home to report what they had seen and enlisted the support of more people. The commanders of the fleet were Simos and Protis. So they came and sought the friendship of the king of the Segobrigii, by name Nannus, in whose territory they desired to found a city. It so happened that on that day the king was engaged in arranging the marriage of his daughter Gyptis: in accordance with the custom of the tribe, he was preparing to give her to be married to a son-in-law chosen at a banquet. So since all the suitors had been invited to the wedding, the Greek guests too were asked to the feast. Then the girl was brought in, and when she was asked by her father to offer water to the man she chose as her husband, she passed them all over and, turning to the Greeks, gave the water to Protis; and he, thus changed from a guest into a son-in-law, was given the site for founding the city by his father-in-law. So Massilia was founded near the mouths of the river Rhone, in a deep inlet, as it were in a corner of the sea.

— Justin XLIII, 3 = Pompeius Trogus. Philippic Histories (transl. Rivet 1988, p. 10).

Other mentions[edit]

In his recounting of the legendary Celtic invasion of Italy said to have been led by Bellovesus around 600 BC, Livy alludes to the founding of Massalia by the Phocaeans. In his version, the latter were facing opposition from the Saluvii, a Celto-Lugurian tribe dwelling further north in the inlands, near present-day Aix-en-Provence. This passage could actually refer to a conflict with Nannos’ son Comanus that occurred ca. 580, or else be part of another ancient tradition telling a less peaceful story of the Phocaean initial coming ca. 600.

While [the Gauls] were there fenced in as it were by the lofty mountains, and were looking about to discover where they might cross, over heights that reached the sky, into another world, superstition also held them back, because it had been reported to them that some strangers seeking lands were beset by the Salui. These were the Massilians, who had come in ships from Phocaea. The Gauls, regarding this as a good omen of their own success, lent them assistance, so that they fortified, without opposition from the Salui, the spot which they had first seized after landing….

A passage from Strabo’s Geographika tells part of the Phocaean journey to the foundation site and focuses on the introduction of the cult of Artemis of Ephesus to Massalia. Strabo tells of an oracle biding the Phocaean colonists to stop in Ephesus, where Artemis appeared to the local Aristarche in a dream. They built a temple to Artemis after arriving in Massalia, making the Ephesian woman the priestess.Plutarch also mentions the legendary founder Protis in his Life of Solon (2, 7): “Some merchants were actually founders of great cities, as Protis, who was beloved by the Gauls along the Rhone, was of Marseille”.

Etymology[edit]

Scholars have compared the name of the princess in Aristotle’s version, Pétta (Πέττα), with the Welsh peth (‘thing’), Breton pezh (‘thing’), Old Irish cuit (‘share, portion’), and Pictish place-names in Pet(t)-, Pit(t)-, which seem to mean ‘parcel of land’. The Medieval Latin petia terrae (‘piece of land’) is also cognate, stemming from the unattested Gaulish *pettia (cf. French pièce). All these terms derive ultimately from Proto-Celtic *kwezdi– (‘piece, portion’). Alternatively, G. Kaibel proposed to emend the name to Gépta (Γέπτα; perhaps ‘the strong’).

The name Prō̃tis (Πρῶτις) is close to protos (‘the first’), and symbolizes concepts of ‘origin’ and ‘primacy’. In Aristotle’s version, he is the son of the Phocaean founder, named Eúxenos, rather than the Phocaean founder himself. After their wedding, Eúxenos (Εὔξενος) changes Pétta’s name to Aristoxénē (Ἀριστοξένη), literally ‘Best Guest/Host’, thus matching his own name, which means ‘Hospitable’. The verb used to designate their alliance, sunṓͅkei (συνῴκει; ‘to live with’, also ‘founding with’), connotes the cohabitation of both the couple and the two groups. The changing of the name may thus describe the hellenization of the natives, who came to live with the Phocaeans, as well as the inauguration of a new patrilineal descent-group, the Protiadae, that broke off from Nannus’ native descent-group. However, Aristotes mentions that the Protiadae “descended from her” rather than from Protis, perhaps alluding to the semi-matrilineal system of the Segobrigii, where small groups were likely founded by women from the dominant tribe but ruled by local ‘big men’.

The local king’s name, Nannus or Nános (Νάνος), means ‘dwarf’ in Greek, which seems to have surprised Aristotle, who insists that this was “actually his name”. It could be interpreted as meaning ‘chieftain, kinglet’ (i.e. ‘little king’).

The name of the second Phocaean commander, Simos, is only given by Trogus and refers to a physical disgrace: a hooked nose or a simian face. According to Pralon, in the Greek tradition, “the defect condemns anyone who suffers from it to exclusion, but can also qualify them for the greatest feats”.

Analysis[edit]

The Phocaean foundation myth revolves around the idea of a peaceful relationship between the natives and the settlers, which contrasted with historical situations where territories could be seized by force or trickery during the Greek colonial expansion. Mixed marriages were a necessary and common practice in the early period of colonization, and such myths probably helped the descendants of both settlers and natives symbolically share a common origin in their collective memory. In Trogus’ version, Protis does not integrate the Segobrigii into the new colony. Instead, the king Nannus provides him with a piece of land to found a city and allow him to preserve his ‘Hellenicity’.

After the capture of Phocaea by the Persians in 545 BC, a new wave of settlers fled towards Massalia, which could explain the presence of the two chiefs (duces classis), Simos and Protis, in Trogus’ version, as well as Strabo’s account of the Ephesian Artemis. According to historian Henri Tréziny, the creation of the single founder, Protis, could even be posterior to the fall of Phocaea in 494 BC. Scholar Bertrand Westphal argues that some archetypes of the foundation myth may have already existed on the shores of Anatolia before 600 BC: in the eyes of Phocaean settlers leaving their Hellenic homeland for the unknown lands of the “Barbarians”, such myths could have served as an encouragement to set sail for foreign shores, with the promise of marrying a princess and leaving a posterity abroad.

The founding myth of Massalia also shares similarities with other tales from Greek mythology. In the Homeric tradition, such myths generally involve aristocratic heroes and indigenous kings who came to follow a Greek way of life via the practice of hospitality by exchanging feasts and presents, with a union eventually sealed by dowry and political alliance. For instance, Alcinous offers Odysseus to marry Nausicaa and to settle in Scheria, just as Gyptis offered herself to the foreigner in order to found the colony in the Phocaean version.

Indo-European analogues[edit]

Several Indo-European myths from the Indic, Greek, and possibly the Iranian tradition, recount similar stories of princesses who choose their future husband during their own wedding or via a competition between the suitors. The Indic tradition codified this peculiar form of marriage and called it svayamvara (‘personal choice’). In Rāmāya, Sita chooses Rama as her husband, as Damayanti chooses Nala after she saw him in a dream in the Mahābhārata, and as Tyndareus lets Helen choose her own husband in Euripides’ Iphigenia in Aulis. Additionally, both Penelope in Homer’s Odyssey and Draupadī in the Mahābhārata make their choice in the form of an archery competition between their suitors.

Athenaeus compared the Phocaean version with an Oriental tale found in Chares of Mytilene’s “Stories about Alexander” (Perì Aléxandron historíai). The princess Odatis, daughter of the king Homartes, sees in her dream Zariadres, the king of Sophene, a land near the Caspian Sea. Zariadres thereafter dreams of Odatis and proposes to her, but she refuses. Shortly afterwards, Homartes summons the lords of his kingdom and a wedding is organized. Odatis is supposed to look at them all, then take a golden cup, fill it and give it to the one with whom she consents to be married, but she delays once again the decision, and the frustrated Zariadre decides to kidnap the young princess. According to Athenaeus, the tale was so popular among “barbarians” that many nobles gave their daughters the name of Odatis. The story is also reminiscent of Ctesias’ tale of Stryangaius and Zarinaia.[20]

In the Massaliot myth, the princess’ choice is actually placed under divine control, or tyche (‘chance’, ‘fate’). Both Aristotle and Trogus agree that the presence of Euxenus/Protis at Prottis/Gyptis’ wedding was fortunate (“Euxenus happened to be visiting when this Nanos was celebrating his daughter’s wedding” ; “It so happened that on that day the king was engaged in arranging the marriage of his daughter Gyptis”). Aristotle insists that the bowl was given to the Phocaean by the princess “either by accident or for some other reason”, and that Nanos “decided that the gift had been made in accord with the god’s will”.

According to Aristotle, a family named Protiadae lived at his time in Massalia, and probably claimed descent from the legendary Prō̃tis (Πρῶτις), whom he portrays as the son of Euxenus and Aristoxene.

The 25th centenary of the city foundation was celebrated in 1899 in Marseille, with a popular feast and the reconstruction of the coming of the Phocaean boats to the Old Port. The 26th centenary was celebrated in 1999, and marked by the creation of a public park named Parc du 26e Centenaire.[22]

The ancient myth inspired Guillaume Apollinaire’s La Fin de Babylone, published in 1914.[23]

References[edit]

Primary sources[edit]

Bibliography[edit]

- Bats, Michel (2021). “L’Artémis de Marseille et la Diane de l’Aventin : de l’amitié à la rupture, entre Marseille et Rome”. In Bouffier, Sophie; Garcia, Dominique (eds.). Les territoires de Marseille antique. Errance. ISBN 978-2-87772-848-5.

- Bouffier, Sophie; Garcia, Dominique (2021). “Variations territoriales: indigènes et Grecs en Celtique méditerranéenne”. In Bouffier, Sophie; Garcia, Dominique (eds.). Les territoires de Marseille antique. Errance. ISBN 978-2-87772-848-5.

- Freeman, Philip (2006). “Greek and Roman accounts of the ancient Celts”. In Koch, John T. (ed.). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

- Garcia, Dominique (2016). “Aristocrates et ploutocrates en Celtique méditerranéenne”. In Belarte, Franco; Garcia, Dominique; Sanmartí, Joan (eds.). Les Estructures socials protohistòriques a la Gàl·lia i a Ibèria. Universitat de Barcelona. pp. 85–94. ISBN 978-84-936769-4-0.

- Koch, John T. (2006). Celtic Culture: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-85109-440-0.

- Kolendo, Jerzy; Bartkiewicz, Katarzyna (2005). “Origines antiques des débats modernes sur l’autochtonie”. Collection de l’Institut des Sciences et Techniques de l’Antiquité. 985 (1): 25–50. ISSN 1625-0443.

- Matasović, Ranko (2009). Etymological Dictionary of Proto-Celtic. Brill. ISBN 9789004173361.

- Morel-Deledalle, Myriam (1999). “Du mythe à la recherche, les célébrations du vingt-cinquième centenaire de la fondation de Marseille”. In Hermary, Antoine; Tréziny, Henri (eds.). Marseille grecque: 600-49 av. J.-C., la cité phocéenne. Errance. ISBN 978-2-87772-178-3.

- Pralon, Didier (1992). “La légende de la fondation de Marseille”. Marseille grecque et la Gaule. Vol. 3. Études massaliètes. pp. 51–56. ISBN 978-2908774030.

- Py, Michel; Tréziny, Henri (2013). “Le territoire de Marseille grecque : réflexions et problèmes”. In Bats, Michel (ed.). D’un monde à l’autre : Contacts et acculturation en Gaule méditerranéenne. Centre Jean Bérard. pp. 243–262. doi:10.4000/books.pcjb.5278. ISBN 978-2-38050-003-5.

- Rivet, Albert L. F. (1988). Gallia Narbonensis: With a Chapter on Alpes Maritimae : Southern France in Roman Times. Batsford. ISBN 978-0-7134-5860-2.

- Tréziny, Henri (2005). “Les colonies grecques de Méditerranée occidentale”. Histoire urbaine. 13 (2): 51. doi:10.3917/rhu.013.0051. ISSN 1628-0482.

- Westphal, Bertrand (2001). Le rivage des mythes: une géocritique méditerranéenne, le lieu et son mythe. Presses Universitaires de Limoges. ISBN 978-2-84287-199-4.

Recent Comments